Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9600

ISSN: 2155-9600

Research Article - (2025)Volume 15, Issue 2

Sobolo is a popular locally produced beverage in Ghana. However, there is limited work done on its physicochemical and microbiological qualities. This study was therefore conducted to determine the physicochemical properties and microbiological quality of sobolo on and around the Koforidua Technical University (KTU) campus. Samples were taken from six Sobolo vending points and their pH, Titratable Acidity (TA), Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Moisture Content (MC) determined. Standard plating methods were used to assess the microbiological quality of the beverage. The results indicate that the pH of Sobolo ranged from 3.85 ± 0.07 to 6.37 ± 0.18, TA from 0.028 ± 0.001 to 0.075 ± 0.001 g/mL, TSS from 2.00 ± 0.00 to 15.44 ± 0.00°Brix and MC from 83.60 ± 0.30 to (96.9 ± 0.10)%. The total viable count ranged from 1.20 × 104 to 9.70 × 104 CFU/mL, fungi levels ranged from 0.00 × 104 to 2.70 × 104 CFU/ mL, Shigella levels were in the range 0.00 × 104 to 1.01 × 104 CFU/mL and the Escherichia coli levels were also in the range from 0.00 × 104 to 9.80 × 103 CFU/mL. Samples from all vending points studied had total viable count below the permissible levels. However, the presence of E. coli in Sobolo obtained from two of the Sobolo vending points is an indication that those samples have been contaminated with faecal matter and are unsafe for human consumption. The Sobolo vendors within and outside KTU should therefore be trained on how to handle the beverage to prevent contamination.

Microbiological quality; Physicochemical properties; Total viable count; Sobolo vending points; Escherichia coli

Non-alcoholic beverages which are made up of many types of liquid refreshment such as Carbonated Soft Drink (CSD), energy drinks, juices, bottled and enhanced water, probiotics and sports drinks were estimated to grow from $160 billion in 2008 to about $190 billion in 2020. Most non-alcoholic beverages found in Ghana are imported and their importation drains the country of its scarce foreign exchange earnings. In Ghana, CSD is one of the most consumed beverages [1].

There are many locally made non-alcoholic beverages in Ghana, including Asana, Fula and Sobolo. Among these, Sobolo enjoys the highest patronage among many people in Ghana and it has now become a household name. Sobolo is a locally prepared nonalcoholic beverage made from the leaves of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdarifffa) plant which is in the family Malvaceae. This beverage has different names in different countries, including Zobo in Nigeria, drink of the Pharaohs in Egypt, Tea karkade in Sudan and da Bilenni in Mali.

Studies have shown that Roselle extract has nutritional and medicinal properties. In a comprehensive review, Roselle extract was shown to possess antibacterial, anti-oxidant, anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive properties.

Koforidua Technical University (KTU) is a tertiary institution located in the eastern region of Ghana. It is a large community made up of a student population of over 6000 and staff population of 500. Students and staff of KTU purchase and consume Sobolo from within the campus and its vicinity on daily basis. The preparation of this beverage goes through so many steps including processing, bottling and storage. These expose it to possible microbiological contamination. Some of these microbial contaminants are pathogenic and may cause diseases such as typhoid, dysentery and enteric fever when contaminated Sobolo is consumed. The health and safety of the staff and students in the community can influence academic work. Illnesses caused to staff and students, of the university, who consume Sobolo contaminated by pathogenic microorganisms, may lead to loss of working days, the cost of purchasing medicine and worst of all may lead to death. The microbiological safety of Sobolo sold in and around the campus of Koforidua Technical University is unknown because no work has so far been carried out on it, so this should be a matter of concern. Many similar studies carried out elsewhere have raised concerns about the microbiological safety of the Sobolo drink. A study carried out in the Accra Metropolis in Ghana revealed that even though microbial contamination of hibiscus tea was observed, it did not significantly affect the microbial quality of the product. In a study conducted by Iwuoha and Eke, highly pathogenic organisms such as Bacillus cereus and Escherichia coli were isolated from Zobo drink in Nigeria. Zobo beverage produced by boiling was found to be microbiologically safer than the one produced through steeping. In addition, the physicochemical properties such as pH, Titratable Acidity (TA), Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and moisture content of Sobolo sold in and around the campus are unknown. These properties influence the microbial stability and hence safety of the beverage. The pH, Titratable Acidity (TA) and Total Soluble Solids (TSS) have also been found to be involved in the erosive ability of beverages on the enamel. The study therefore sought to look at the microbial safety of Sobolo and how some of its physicochemical properties influence its microbial safety [2].

Study area

The area for the study was the New Juaben Municapality in the eastern region of Ghana. Six Sobolo vending points in the community were selected purposively for the study (Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1: Map showing the study area.

Sample collection

A preliminary study was conducted on the consumption pattern of Sobolo by students and staff of KTU and the results indicated the Sobolo drink is purchased from six different locations. Bottled Sobolo samples were therefore purchased from vendors at these six different locations from campus and outside the campus of KTU in the New Juabeng Municipality of Koforidua in the eastern region of Ghana. The samples were then put under refrigeration until needed for analysis. The Sobolo samples purchased from the various places were coded as A, B, C, D, E and F [4].

Microbiological analysis

The microbial counting and identification were done in accordance with standard procedures. During the procedures, microbial contamination of materials were avoided through sterilization of all media and glassware at 121°C and 15 psi for 15 minutes and the use of aseptic techniques. The Sobolo sample (1 mL) was pipetted and diluted with 10 mL of distilled water and further serial dilutions were made to get 10-4. The pour plate method was employed using standard protocols for identification and enumeration of microorganisms and plating was replicated for each dilution (from 10-1 to 10-4). Nutrient agar was used to determine the total viable count, the Sabouraud dextrose agar was used to culture yeast and mould (fungi) and Mckonkey agar was used for coliform colonies and blood agar for fastidious bacteria. The plates for the total variable count and total coliform were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and those for fungal growth were incubated for 5-7 days at 28°C. The morphology of the colonies, gram staining and biochemical tests were used to confirm the various bacterial pathogens. The morphology of the colonies was examined and grouped according to shape, colour, border, texture and general appearance of an individual colony of bacteria on each plate. Bacteria were examined with the x 100 objective lens as either gram positive or gram negative based on their staining characteristics. The gram positive cocci bacteria were identified using catalase and coagulase tests. The gram negative bacteria, however, were identified using the biochemical test such as motility, indole, citrate, urease, oxidase and fermentation tests [5].

Determination of physicochemical qualities of Sobolo

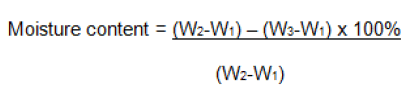

The physicochemical qualities of Sobolo determined were pH, Titratable Acidity (TA), Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Moisture Content (MC). The pH of the Sobolo samples was determined using a pH meter. The standard solutions of 7.0 and 4.0 were used to standardize the pH meter. The electrode of the meter was then inserted into the Sobolo and the pH was measured and recorded when the value became stable. The TA was determined by titrating 0.1 N solution of sodium hydroxide against 10 mL of the Sobolo beverage using phenolphthalein as the indicator and the results expressed as percent citric acid. The TSS was measured using a portable refractometer. The refractometer was calibrated with distilled water and then a drop of the Sobolo beverage put on the glass. The refractometer was shown to light and the point where the white and blue lines met was measured as the TSS of the Sobolo. MC was determined using the hot oven method. A dry crucible was weighed with a balance when empty (W1). Sobolo sample was poured into the crucible and the weight of crucible and Sobolo determined (W2). It was then placed on a hot oven and dried at 130°C for 24 hours. The weight of the crucible and the dried sample was determined (W3). The loss in weight was regarded as the moisture content and was expressed as:

Analysis of data

All measurements were made in duplicates. The data obtained from the study was processed using Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS), Version 17.0 and analyzed using various statistical tools. The means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range tests. Means were deemed to be significant at P<0.05 [6].

Demographic data

The demographic data of the respondents are shown in Table 1. From the study the males constituted 54.8% whiles the females were made up of 45.2%. Most of the respondents were therefore males. The respondents of the study were made up of academic staff, administrative staff, students and national service personnel of KTU. The majority of the respondents were students, which constituted 71.5%. The study sought to find out the extent of consumption of Sobolo on the campus of KTU. Out of 501 respondents who were issued with questionnaires, 453 representing 92.3% indicated that they have consumed Sobolo before. Majority of the respondents were Sobolo consumers [7-10].

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 269 | 54.8 |

| Female | 222 | 45.2 |

| Total | 491 | 100 |

| Respondent category | ||

| Academic staff | 43 | 8.8 |

| Administrative staff | 42 | 8.6 |

| Student | 351 | 71.5 |

| National service personnel | 50 | 10.2 |

| Part time staff | 5 | 1 |

| Total | 491 | 100 |

| Respondent category | ||

| Consumers of Sobolo | 453 | 92.3 |

| Non consumers of Sobolo | 38 | 7.7 |

| Total | 491 | 100 |

Table 1: Demographic information.

Physicochemical properties of Sobolo

The physicochemical properties of Sobolo are shown in Table 2. The Moisture Content (MC) of the beverages from the six locations ranged from 83.60 ± 0.30% to 96.9 ± 0.10%. High MC is known to encourage the growth of spoilage bacteria. Therefore from the results, the susceptibility of the Sobolo samples to microbial growth would be different for the different samples. The results of the present study are in agreement with the MC values of 88.46-88.88% and 94.5 ± 0.5 to 95.1 ± 0.4% obtained for Zobo in previous studies. The pH values obtained for the beverage samples ranged from 3.85 ± 0.07 to 6.37 ± 0.18, which were less acidic when compared with 2.94 and 3.40. Other studies also reported pH range 2.0 to 5.2, 2.50 to 2.67 and 2.9-4.3 for Zobo drinks and are comparable to values obtained in this study. The critical pH at which beverages can cause demineralization of the enamel is 5.5. More than half of the Sobolo samples (66.7%) recorded pH values less than or equal to 5.50 and therefore, they will potentially cause dental demineralization. The Total Soluble Solids (TSS) of the Sobolo samples studied ranged from 2.00 ± 0.00 to 15.44 ± 0.00°Brix. TSS value of 15.00°Brix was reported. The TSS values obtained in the present study are comparable to 10.78 ± 1.28 to 11.61 ± 1.09°Brix and 12.8 ± 1.12 to 13.56 ± 1.07°Brix for the beverages, orange juice and apple juice respectively [11].

| Sample source | pH | Titratable acidity (% citric acid) | TSS | Moisture content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.85 ± 0.07d | 0.075 ± 0.001a | 15.44 ± 0.00a | 83.60 ± 0.30d |

| B | 6.37 ± 0.18a | 0.044 ± 0.002b | 7.15 ± 0.07d | 88.00 ± 2.60c |

| C | 5.50 ± 0.01b | 0.032 ± 0.006c | 10.30 ± 0.14b | 88.18 ± 0.17c |

| D | 6.27 ± 0.24a | 0.028 ± 0.001c | 7.15 ± 0.07d | 92.75 ± 0.07b |

| E | 4.15 ± 0.07c | 0.030 ± 0.001c | 2.00 ± 0.00e | 96.9 ± 0.10a |

| F | 3.90 ± 0.14cd | 0.045 ± 0.002b | 9.30 ± 0.14c | 88.2 ± 0.30c |

| Note: Means are triplicate measurements. Means in the same column with different alphabets are significant at P<0.05 | ||||

Table 2: Physicochemical properties of Sobolo.

Microbiological analysis

The results on microbiological analyses of the Sobolo samples are shown in Table 4. The Total Viable Count (TVC) values give the general indication of the microbiological quality of a food product, but cannot be used to predict the safety of the product. The TVC values obtained in this study ranged from 1.20 × 104 to 9.70 × 104 CFU/mL. From Table 3, TVC 106 is considered good for category B ready-to-eat foods such as Sobolo. All the TVC values of the samples in the present study were lower than 106 CFU/mL and therefore could be considered as good, in terms of their microbial quality. However, this does not necessarily indicate that the Sobolo samples are safe [12].

| Sample source | Total viable count (CFU/mL) | Yeast and mould (CFU/mL) | Shigella (CFU/mL) | Escherichia coli (CFU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.00 ×104 | 6.90 × 103 | 0.00 × 104 | 7.30 × 103 |

| B | 7.30 × 104 | 1.62 × 104 | 1.01 × 104 | 9.80 × 103 |

| C | 6.60 × 104 | 7.80 × 103 | 0.00 × 104 | 0.00 × 103 |

| D | 1.20 × 104 | 7.00 × 102 | 0.00 × 104 | 0.00 × 103 |

| E | 9.70 × 104 | 0.00 × 104 | 1.00 × 104 | 0.00 × 103 |

| F | 7.10 × 104 | 2.70 ×104 | 9.00 × 103 | 0.00 × 103 |

Table 3: Microbial count (CFU/mL) of Sobolo drink.

| Food category | Microbial quality (CFU/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Acceptable | Unsatisfactory | |

| A | <104 | <105 | ≤ 105 |

| B | <106 | <107 | ≤ 107 |

| C | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Indicators | |||

| Shigella | <102 | 102 to <104 | ≥ 104 |

| E. coli | <3 | 3 to <102 | ≥ 102 |

| Note: A: Ready-to-eat foods with all components fully cooked for immediate sale or consumption (e.g. meat pie); B: Ready-to-eat foods which are fully cooked with further handling or processing before consumption (e.g. custard filled pastry); C: Food which contains uncooked fermented ingredients or fresh fruit and vegetables (e.g. takeaway fruit and yoghurt mix); N/A=Not available | |||

Table 4: Guidelines for determining the microbial quality of ready-to-eat foods.

The Shigella spp. levels found in the Sobolo samples ranged from 0.00 × 104 to 1.01 × 104 CFU/mL. Out of the six samples of Sobolo studied, only two had levels ≥ 104 and this is regarded as unsatisfactory. Even for the sample, where the levels of Shigella spp. were 102 to Ë104 CFU/mL and are considered to be acceptable, they can cause diseases. It has been found out that Shigella dysenteriae serotype 1, S. flexneri or S. sonnei cause illness at dose of 10, 100 and 500 organisms respectively. These bacteria belong to the Enterobacteriaceae, which is an indicator species and its presence in ready-to-eat food shows that there was post-process contamination or inadequate cooking. Shigella spp. are transmitted by the faecal oral route by either person-to-person contact or consumption of contaminated food or water. Shigella spp. causes shigellosis (bacillary dysentery). It is also known that under frozen (-20°C) or refrigerated (4°C) conditions, Shigella spp. can survive for extended periods of time [13-15].

In addition, another indicator species, E. coli was detected in samples from two locations. The levels of E. coli were greater than ≥ 102 and the microbiological quality of these samples are therefore unsatisfactory. In ready-to-eat foods, the presence of E. coli is an indication of poor food hygiene and sanitation or inadequate heat treatment. Many other authors have also detected E. coli in Zobo drinks [16].

The total fungi levels in the Sobolo were in the range 0.00 × 104-2.7 × 104 cfu/mL. The values are in agreement with 0.9 × 104 cfu/mL obtained in a previous study for Sobolo prepared in the laboratory [17].

The bacteria present in the Sobolo samples were identified using the criteria shown in Table 5.

| Bacteria identified | Gram stain reaction | Catalase | Motility | Indole | Citrate | Urease | Oxidase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | - | - | + | + | - | - | - |

| Shigella | - | + | - | Variable | - | - | - |

| Note: No reaction observed (-), Reaction observed (+), Gram-negative, indole-positive, citrate-negative, with red mucoid and slightly raised colonies from McConkey plates were identified as E. coli. Shigella was identified as gram-negative, citrate-negative, catalase-positive and oxidase-negative | |||||||

Table 5: Gram stain reaction and biochemical identification of microbes.

The physicochemical properties and microbiological quality of Sobolo were studied. The results have shown that Sobolo sold on and around the campus of KTU are of comparable physicochemical properties to those of Sobolo studied by other authors and also with beverages like orange juice and apple juice. Therefore, in terms of their physicochemical properties, the Sobolo samples studied are acceptable for consumption.

Some of the Sobolo samples were contaminated with E. coli and Shigella, indicating inadequate cooking of the beverage or postprocess contamination and are therefore not safe for consumption. It is therefore important that vendors of Sobolo within and outside KTU campus are trained to handle the production, bottling and storage of the Sobolo drink to avoid any form of contamination.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Owusu J, Nartey E, Arkorful DA, Amissah A, Gamor E (2025) Microbiological Quality of Sobolo a Ghanaian Traditional Beverage of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) Plant. J Nutr Food Sci. 15:59.

Received: 06-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. JNFS-23-27932; Editor assigned: 09-Nov-2023, Pre QC No. JNFS-23-27932 (PQ); Reviewed: 23-Nov-2023, QC No. JNFS-23-27932; Revised: 01-Apr-2025, Manuscript No. JNFS-23-27932 (R); Published: 07-Apr-2025 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-9600.25.15.59

Copyright: © 2025 Owusu J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.