Journal of Down Syndrome & Chromosome Abnormalities

Open Access

ISSN: 2472-1115

ISSN: 2472-1115

Case Report - (2023)Volume 9, Issue 1

Down Syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal abnormality in live born infants. Although limited research suggests that autonomic dysfunction may be more common in the setting of DS, a predisposition to cardiac conduction abnormalities is not well recognized. We performed a retrospective review of records at our tertiary referral centre from Jan 2018 to Jan 2021 to identify people who had Down’s syndrome and required permanent pacemaker implantation for cardiac conduction disease. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, and without a structural cardiac abnormality. Three individuals were identified aged between 41 and 59 years; two were female and one was male. All presented with recurrent syncope with sinus pauses (2-10 seconds) identified on Holter monitor (n=2) or loop recorder (n=1). All three patients underwent dual chamber permanent pacemaker insertion under general anesthesia with no short or long term complications over the follow-up period (11-46 months). One of the three patients had mild self-limiting pre-syncopal episodes three months post-pacemaker implantation which resolved following the commencement of 100 mcg fludrocortisone daily. Young people with DS may be predisposed to sinus node dysfunction; rhythm monitoring is recommended in the setting of suspicious symptoms. People who have Down Syndrome may have an increased risk for sinus node dysfunction compared with the general population. Heart rhythm assessment should be considered in the setting of suspicious symptoms.

Down syndrome; Permanent pacemaker; Autonomic dysfunction; Cardiovascular care

Down Syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal abnormality in live-born infants [1]. With improving care and medical treatment, mean life expectancy of children with Down Syndrome (DS) has increased to approximately 60 years [2]. While cardiovascular abnormalities are common, relevant guidelines and data are lacking in this cohort.

Autonomic dysfunction is prevalent in individuals with Down Syndrome (DS) [3]. Overall, physical work capacity is reduced; chronotropic incompetence, significantly reduced heart rate and blood pressure responses to autonomic tasks (such as exercise and the tilt test) have been reported [4]. The long-term implications of altered autonomic dysfunction in Down Syndrome (DS) have not been studied. Autonomic dysfunction has been associated with bradycardia sometimes requiring Permanent Pacemaker implantation (PPM) in the general population and in people who have Parkinson’s disease [5].

We retrospectively reviewed records at our adult tertiary centre to identify people who have Down Syndrome (DS) and required permanent pacemaker implantation between January 2017 and January 2022.

Patient 1

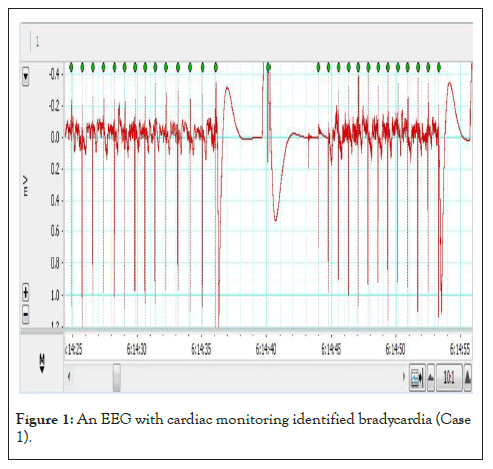

A 39 year old female was referred to a neurologist after several near-syncope episodes thought to be seizure related. An Electroencephalogram (EEG) with cardiac monitoring identified possible bradycardia (Figure 1). As part of her workup she had a 48 hour Holter monitor, who found 10 second sinus pauses that correlated with self-reported episodes of near syncope. Medical history included Raynaud’s disease, hypothyroidism (adequately supplemented), coeliac disease, and premature menopause. Medications included thyroxine, esomeprazole, vitamin D and fish oil. Her examination was unremarkable apart from typical physical features of Down Syndrome (DS) and a short mid-systolic murmur, loudest at the upper left sternal edge. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated sinus bradycardia.

Figure 1: An EEG with cardiac monitoring identified bradycardia (Case 1).

Her pre-syncope workup included an EEG (no seizure activity recorded), Computerised Tomography (CT) aortogram, and a Trans-Thoracic Echocardiogram (TTE). An incidental pulmonary embolus was found on the CT aortogram, and she was sent to her local emergency department. The thrombolytic screen was negative, and she commenced rivaroxaban and ceased hormone replacement therapy. The TTE found mild pulmonary valve dysplasia and regurgitation, with a mobile interatrial septum and patent foramen ovale; a bubble study did not demonstrate any right to left shunting across the patent foramen ovale. The diagnosis was sick sinus syndrome, and PPM insertion was recommended.

A cardiac electrophysiologist inserted her dual chamber PPM (Medtronic Azure, XT DR MRI) under general anaesthesia with no issues reported. Four days later PPM interrogation found satisfactory lead parameters.

Post-pacemaker implantation, the severe near-syncopal and syncopal episodes ceased, however four months later she presented to her cardiologist with recurrent milder pre-syncopal symptoms on standing. PPM interrogation found lead parameter to be stable and satisfactory, atrial pacing had been delivered on 40% heart beats and ventricular pacing on <0.1% heart beats. Postural hypotension was noted by her cardiologist, most likely consequence of autonomic dysfunction. A small dose of oral fludrocortisone (100 mcg mane) was commenced, and autonomic testing was not pursued due to good treatment response; morning cortisol was within normal range. She has been well over 23 months of follow-up.

Patient 2

A 48 year old female was referred to a cardiologist with three episodes of collapse over three years. The first event occurred while shopping, where she was found lying on the floor of the shop. On another occasion she was observed to drop to the ground during physical exertion; she was very pale but did not completely lose consciousness. On the third occasion she lost consciousness for a few seconds after significant physical exertion, while standing and waiting to enter a lift. No seizure activity was observed.

Cardiac history included a small patent ductus arteriosus, and a dysplastic pulmonary valve with mild pulmonary regurgitation. Other medical history included hypothyroidism (adequately supplemented). Regular medications were thyroxine, hormone replacement therapy and esomeprazole. Aside from dysmorphic features, the examination was unremarkable. Baseline ECG showed sinus rhythm with subtle ventricular pre-excitation.

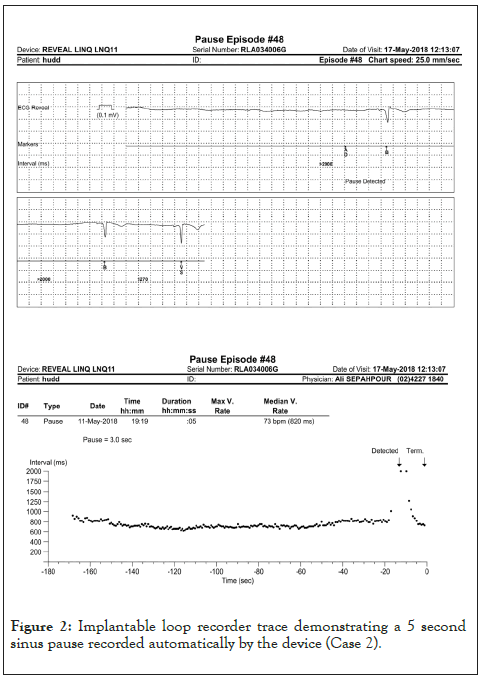

There was a high-suspicion for neurocardiogenic syncope but 24 hour Holter monitoring only demonstrated rare isolated atrial (15 beats, <1%) and ventricular (3 beats, <1%) ectopic beats, one 3-beat run of idioventricular rhythm, and rare pauses due to non-conducted p-waves (longest 2.3 seconds), and so a loop recorder was implanted. It documented fifty one sinus pauses lasting more than three seconds. The longest pause lasted for seven seconds while awake, with PR interval shortening and minimal sinus rate slowing prior (Figure 2). Given these loop recorder findings and symptoms, the cardiologist recommended replacing the loop recorder with a PPM.

Figure 2: Implantable loop recorder trace demonstrating a 5 second sinus pause recorded automatically by the device (Case 2).

The PPM was inserted under general anesthetic. Axillary vein access was employed to implant an active fixation pacing lead (53 cm length, due to the patient’s small stature) at the low right ventricular septum. Attempts at implanting a right atrial lead (shorter lead length unavailable) were abandoned due to difficult manoeuvrability with regards to finding a stable lead position, and the atrial port was plugged. While the lead was temporarily in the right atrium, the accessory pathway effective refractory period was estimated to be 460 msec based on accessory pathway block at an atrial pacing rate of 130 bpm. Adenosine 12 mg Intravenous (IV) injection resulted in sinus rate slowing with shortening of the PR interval and more pronounced pre-excitation. Following PPM implantation, the loop recorder was explanted. Based on the absence of supraventricular tachycardia on loop recorder traces and the recorded pathway refractory period, it was not deemed necessary to ablate the accessory pathway. She has been well over 48 months of follow-up, with no documented arrhythmia on pacing checks.

Patient 3

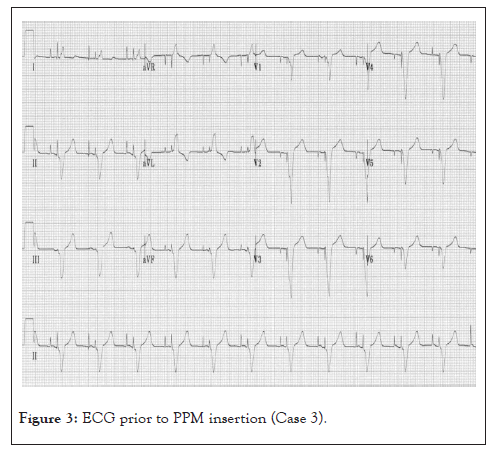

A 59 year old male presented to a cardiologist after his dentist had noted bradycardia. For several months prior to this he had been experiencing fainting spells. On one occasion the patient had a headache which was accompanied by a syncopal episode without injury. On at least two other occasions he experienced seated syncope. His medical history included gout and a mildly calcified aortic valve, and medications were allopurinol and cholecalciferol. On examination, he had typical physical features of Down Syndrome (DS) and a short ejection systolic murmur, loudest at the upper right sternal edge. He was noted to be sleepy at times but the family opted not to pursue a sleep assessment. ECG demonstrated sinus bradycardia with second degree atrioventricular block mobitz type 2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: ECG prior to PPM insertion (Case 3).

Twenty four hour Holter monitoring documented sinus bradycardia with short episodes of 2:1 second degree heart block. Four pauses lasting 2.0 second or more were noted, the longest lasting 3.8 seconds; all the episodes occurred during wakefulness and no symptoms were reported during the test. Average heart rate was 62 bpm over 24 hours. His syncope was thought to be most likely related to sinus node disease. PPM insertion was recommended.

Dual chamber pacemaker insertion was performed under general anaesthesia, and the patient had mild post-operative urinary retention which self-resolved. At most recent follow-up he was atrially paced 74% of the time. There was no ventricular pacing. At 12 month follow-up he was well and symptom free.

This case series describes three relatively young adult patients with Down Syndrome (DS) who required permanent pacemaker insertion after pre-syncopal and syncopal episodes in the setting of predominantly sinus node dysfunction. In all three, symptoms were not immediately investigated or assumed to be related to cardiac arrhythmia.

While congenital heart disease is well-recognized to be associated with Down Syndrome (DS), a predisposition to other cardiovascular conditions is less clearly characterised. Our data suggest that sinus node dysfunction may be more common in people who have Down Syndrome (DS). Based on the catchment size of our tertiary centre, a presumed prevalence of Down Syndrome (DS) of one in 1000 and expected rates of sinus node dysfunction in the general population aged 45-65 years [6], people with Down Syndrome (DS) were more likely to have sinus node dysfunction (p<0.0001 on Chi Square test). Only one other study has reported sinoatrial node disease in individuals with Down Syndrome (DS) without congenital heart disease. This study presented four patients who presented to their local hospital with syncope; two of these patients were uncooperative with medical staff leading to delayed diagnosis, and the other two patients were given the provisional diagnosis of atonic seizures. Our cohort was younger (median 48 vs. 55 years), included female patients (66%), and was based in Australia (vs. the UK). Of note, this series of patients also experienced considerable delay in reaching the diagnosis of sinoatrial node disease. Diagnostic delays in both reports related to alternative diagnoses (particularly neurological) being considered first, and difficulties in obtaining an accurate history of the syncopal events [7].

It is unclear why people with Down Syndrome (DS) may be predisposed to sinoatrial disease. We postulate that the phenomenon of premature ageing and prevalence of autonomic dysfunction in patients with Down Syndrome (DS) may contribute to an increased incidence of sinoatrial disease, and further research should explore the potential mechanisms [8,9]. There is also a need for formal guidelines for clinicians focused on cardiovascular care in Down Syndrome (DS) [10].

To find individuals with Down's syndrome who required permanent pacemaker installation due to cardiac conduction disorders, we conducted a retrospective analysis of data at our tertiary referral centre from January 2018 to January 2021. People who have Down Syndrome (DS) may have an increased risk for sinus node dysfunction compared with the general population. Heart rhythm assessment should be considered in the setting of suspicious symptoms.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was provided by the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Research Ethics and Governance Office, and all patients were consented for the inclusion of their de-identifiable medical data in this publication (Ref X21-0373 & 2021/ETH11852).

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or guardians for publication of this Case Series including any accompanying figures. A copy of consent forms are available for review by the editor of this journal.

Citation: Chadwick V, Medi C, McGuire M, Sepahpour A, D’Ambrosio P, Celermajer DS, et al. (2023) Sinus Node Dysfunction in People who have Down Syndrome with Structurally Normal Hearts: A Case Report. J Down Syndr Chr Abnorm. 9:215.

Received: 20-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JDSCA-23-21561; Editor assigned: 22-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. JDSCA-23-21561 (PQ); Reviewed: 09-Mar-2023, QC No. JDSCA-23-21561; Revised: 16-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. JDSCA-23-21561 (R); Published: 23-Mar-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2472-1115.23.9.215

Copyright: © 2023 Chadwick V, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.