Journal of Tourism & Hospitality

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0269

ISSN: 2167-0269

Research Article - (2023)Volume 12, Issue 5

This study investigates the impact of mentorship functions on the organizational performance of novice tour leaders in the travel industry, with a specific emphasis on exploring potential interference from psychological ownership. The primary objectives of this research are to establish and assess relationships between various variables related to mentorship functions and organizational performance within the travel industry while considering the influence of psychological ownership among novice tour leaders. The research methodology employed a comprehensive approach, including questionnaire development and data analysis. This study was conducted in three distinct phases, guided by an extensive review of relevant literature in the field. After questionnaire design, a survey was administered to 301 novice tour leaders from various travel agencies. Participants provided ratings on multiple parameters using a 5-point Likert scale. Subsequently, the collected data underwent statistical analysis and interpretation using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0. The findings reveal that mentorship functions within the travel industry and the levels of psychological ownership among new team leaders exert significant interference effects on organizational performance. Importantly, the degree of psychological ownership, whether high or low, influences the relationship between mentorship functions and organizational performance. These results underscore the critical roles played by mentoring and psychological ownership in shaping the performance of tour leaders in the travel industry.

Newbie tour leader; Mentoring function; Psychological ownership; Organizational performance

Since the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic at the end of 2019, it has spread at an unprecedented pace, posing a threat to the health and lives of millions of people worldwide. Most countries have implemented lockdowns and mandatory quarantines, weakened the global economy and paralyzed the tourism industry. This has led to a gradual decline in the travel and tourism-related sectors, indirectly causing a predicament for tour leaders who have no groups to lead and prompting the travel industry to reevaluate and restructure. Currently, the literature predominantly discusses the positive effects of mentorship relationships and Psychological Ownership on various aspects, including mentorship relationships and organizational performance, as well as the mediating effects of mentorship relationships, psychological ownership, and organizational performance. However, there is limited discussion about the moderating effects of psychological ownership on mentorship relationships and organizational performance. Additionally, there is a need to consider whether the so-called "mentorship function" can be beneficial to the organizational performance of the travel industry in the post-pandemic era. Furthermore, the role of Psychological Ownership in enhancing the overall service quality of travel itineraries for newbie tour leaders is a topic that warrants exploration [1,2].

Define mentorship as a systematic knowledge and experience transfer process within an organization, facilitated by senior experienced supervisors or colleagues, to help new or less experienced colleagues integrate into the organization quickly and enhance their job competence. Mentorship functions refer to the systematic transfer of knowledge and experience by senior experienced supervisors or colleagues within an organization to assist new or less experienced colleagues in integrating into the organization quickly and enhancing their job competence. The relationship developed through this process, bridging the mentor and the learner, is referred to as a mentorship relationship [3]. Furthermore, collectively term the functional benefits derived from such mentorship relationships as mentorship functions [4,5].

The concept of psychological ownership to explain personality dimensions, stating that it is a sense of possession regarding tangible or intangible objectives. It represents an extension of self in matters one owns and includes core dimensions such as selfconcept, belongingness, attitude, and responsibility. Additionally, proposed mechanisms and outcomes of the employee Psychological Ownership framework (antecedents, pathways, and consequences) concluded that (1) Psychological location is inherent in humans, (2) Psychological location (or Psychological Ownership) can be generated for both tangible and intangible objects (goals), and (3) Psychological position (or Psychological Ownership) influences objects with significant emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral implications [6,7].

Regarding the measurement of organizational performance, scholars explain that different viewpoints and assessments exist due to differences in data acquisition and perception (including Human Resource Development (HRD) needs assessment, Human Resource Management (HRM) performance management, performance improvement, organizational development, human capital, etc.). Categorized 30 studies and summarized the following evaluation criteria for organizational performance: productivity, profitability, resource acquisition, environmental mastery, efficiency, employee retention, growth, survivability, and others. Organizational performance requires the implementation of company strategies into actionable goals, metrics, and targets, which are then incorporated into daily management to drive strategy execution [8-10].

This study aims to investigate whether the psychological ownership variables of newly hired tour leaders in the comprehensive travel industry, categorized as high/low, have a moderating effect on organizational performance variables based on mentorship function variables. This forms the basis of the research motivation and purpose of this article.

Theory of tour leader, mentoring function, and psychological ownership

Recently, scholars have been continuously discussing and understanding the factors that lead to increased organizational performance, job retention intentions, and service quality [11]. This employee behavior is particularly crucial in the travel industry because it is associated with enhancing service quality, customer service experiences, and employee engagement [12,13]. Lately, there has been a growing interest in understanding how employees' feelings or psychological attachment to the organization influence their attitudes and behaviors toward the organization [14]. Therefore, the concept of psychological ownership has become a key framework for comprehending how employees' feelings translate into their positive attitudes and behaviors toward the organization.

Tour leaders (newbie/senior): Tour leaders are individuals who provide services and receive compensation for guiding groups of international tourists during their travel. When dispatched by a travel agency, tour leaders represent the company in serving international tourist groups. In addition to fulfilling various agreements outlined in the travel documents signed with clients, tour leaders are responsible for ensuring passenger safety, handling unforeseen incidents appropriately, and upholding the company's reputation and image. They possess a wealth of knowledge in the field of tourism, along with excellent foreign language communication skills. During their service, tour leaders play various roles [15-20].

Newly appointed tour leaders entering the travel industry may not have fully matured knowledge and skills. However, they can initially acquire the necessary knowledge through training provided by their company or organization. In addition to this skill training, we can analyze the professional abilities of tour leaders based on three main dimensions: "Professional knowledge," "group-leading skills," and "work attitude." Professional knowledge can be assessed through certification examinations, and knowledge accumulation can be enhanced by accessing the latest information and updates from journals and magazines issued by tourism authorities or tour leader associations. Information on training activities can be gathered from relevant websites or by connecting with professional organizations [21].

Experienced tour leaders, willing to take on the role of mentors, can help shorten the gap for newly appointed tour leaders, both in terms of job performance and interpersonal relationships within the organization. Past failures can serve as valuable learning experiences, and continuous efforts and accumulating experiences from mistakes can reduce the probability of errors. Throughout this process, guidance and instruction from mentors or senior tour leaders provided over an extended period and in a detailed manner, are often required to point out lessons learned from past failures. This study defines newly appointed tour leaders in the travel industry as those with less than one year of experience [22-24].

Mentoring functions: Introduced the concept of mentorship as a strong interpersonal interaction between a seasoned and experienced mentor and a less-experienced protégé or peer. In this process, the protégé is nurtured under the mentor's wing, receiving guidance, support, career direction, and personal development. It is a complex and multifaceted interaction. Subsequent research has explored this concept, confirming that mentorship functions can directly impact employee attitudes, behaviors, and organizational effectiveness. Hence, it is advocated that organizations should emphasize and promote the establishment of mentorship functions [25-30].

Through this function or system, mentors and protégés can enhance the quality of their relationship and build trust [31]. Protégés can quickly adapt and learn the necessary knowledge and skills through the guidance of their mentors, while mentors gain satisfaction and recognition from their protégés or others [32-34].

The definition of mentorship function for newly appointed tour leaders encompasses the exchange process between mentors and protégés, including the sharing of knowledge by mentors and learning by protégés. This process aims to enhance the capabilities of the protégés (newbies) and help the organization continuously progress and improve its overall performance categorized mentorship functions into career-related functions and psychosocial functions, while further divided psychosocial functions into social support functions and role modeling functions [35-37]. Subsequent researchers often use these three dimensions as the constructs of mentorship functions [38].

Therefore, mentors must maintain a positive role model to facilitate comprehensive knowledge transfer and modeling effects. Scholars have validated the reduced Mentorship Functions

Questionnaire (MFQ-9), which consists of 9 items and exhibits good reliability and validity [39]. MFQ-9 categorizes mentorship functions into "career support" functions, "psychosocial support" functions, and "role modeling" functions. This study extends this discussion and suggests that a high level of mentorship function provides opportunities for overall performance enhancement in organizations [40-45].

The relationship between mentoring function and organizational ownership

Identified three main pathways (or mechanisms) through which psychological ownership arises and highlighted the three core elements at the heart of psychological ownership [46].

Efficacy and effectance: This pathway stems from the desire to experience a sense of causal efficacy when changing one's environment. It leads to attempts to assert ownership and the emergence of a sense of ownership. In other words, people seek to possess and have a sense of ownership because it gives them a feeling of control and effectiveness in shaping their surroundings [47].

Self-identity: This element suggests that individuals use ownership to define themselves and express their self-identity to others. It ensures the continuity of one's self-concept over time [48]. In essence, people use ownership as a means of self-expression and self-definition, and it becomes an integral part of their identity.

Having a place: People invest significant energy and resources into objects or domains that may become part of their inner private sphere, often referred to as their "home." This inner motivation, coupled with the possibility of satisfying it through ownership, drives individuals to dedicate themselves to particular goals and possessions that can become an integral part of their personal space and identity [49,50].

These three core elements underscore how psychological ownership is deeply intertwined with human motivation, identity, and the desire for control and effectiveness in one's environment. It manifests as a profound sense of attachment to objects or domains that individuals perceive as extensions of themselves, influencing their behaviors, attitudes, and choices [51-54].

Since the core of psychological ownership lies in an employee's psychological sense of ownership over a specific matter, employee satisfaction depends on whether their emotions and needs are satisfied [55]. Psychological ownership, which includes self-efficacy, self-identity, and sense of belonging (here, translating the concept of psychological ownership into self-efficacy, self-identity, and sense of belonging), can precisely fulfill these personal needs. When employees feel a sense of psychological ownership toward the organization (in this case, transforming the original concept of Psychological Ownership into self-efficacy, self-identity, and sense of belonging), it enhances job satisfaction, consequently leading to organizational commitment [56]. In other words, employees who experience psychological ownership have a psychological attachment and a sense of belonging to the organization, which results in an attitude of organizational commitment [57].

Therefore, self-efficacy, affects an individual's performance motivation. When individuals believe in their ability to complete tasks, their motivation to complete those tasks is higher [58]. If provided with negative feedback, individuals with high self-efficacy will redouble their efforts, while those with low self-efficacy may not make the same effort [59]. In summary, this study adjusts the three factors of the original psychological ownership (namely, self-efficacy, self-identity, and sense of belonging) to self-efficacy, self-identity, and sense of belonging. Self-efficacy is demonstrated in the confidence to face challenges and the belief in one's overall ability to complete tasks. Psychological ownership makes employees perceive the organization as an extension of themselves. Therefore, when the organization succeeds, employees attribute it to their success. This study posits that if employees perceive their success as linked to the organization, it will reinforce the positive development and cyclical nature of psychological ownership, with these two aspects mutually reinforcing each other.

Organizational performance is a measure of the extent to which an organization achieves its goals and is an accumulation of the processes and outcomes of all its operations. It is a complex but crucial concept. Organizational performance can be divided into two different definitions: Narrow performance, which refers to financial indicators that reflect the fulfillment of company objectives; and from a broader perspective, organizational performance is referred to as company performance, encompassing financial indicators (such as revenue and return on assets) and operational indicators (such as product quality and market share). Therefore, the definition of organizational performance can vary depending on the research approach adopted by researchers. In this study, organizational employee service performance within the comprehensive travel industry in Taiwan is considered the dependent variable. Used productivity as a measure in their research, which encompasses both capital productivity and labor productivity. Financial performance in the comprehensive travel industry is often considered confidential and not easily accessible. Organizational performance includes factors such as alignment with the organization's vision and goals, operational efficiency, establishment of systems, coordination among members, as well as interactions with external stakeholders, and satisfaction of service recipients. Therefore, this study follows the suggestion for measuring organizational performance, which is regarded as an outcome of organizational and human activities. Subjective measurement is employed in this study, with new tour leaders providing subjective assessments based on the operational overview within the travel industry. Multiple indicators are used for this assessment.

The relationship between career mentorship functions and job performance

Young, inexperienced managers can enhance their abilities and job effectiveness under the guidance of experienced mentors through learning, emulation, and taking on challenging assignments. Research indicates that by transmitting information related to organizational role-playing, career functions can reduce protégés' role ambiguity and indirectly impact employee job performance. Mentorship functions have a positive impact on both organizational commitment and job performance also point out a significant relationship between mentorship functions, organizational career satisfaction, interpersonal relationships, and in-role performance. Additionally, employees who receive support through mentorship functions tend to experience higher levels of job satisfaction, performance, and organizational commitment.

It has been found that career functions alone significantly affect job performance, and career functions can influence employee attitudes, behaviors, and effectiveness. Other empirical studies also fiveconfirm that career functions have a positive relationship with job performance. Based on a prior discussion, the following hypothesis is listed.

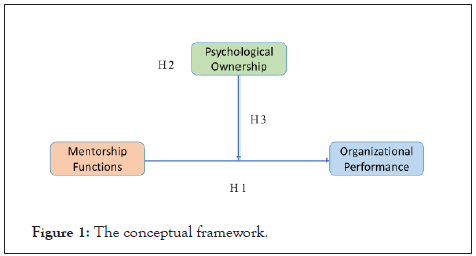

H1: Mentorship functions have a significant positive impact on organizational performance.

The relationship between psychological ownership and organizational performance

Mentors can provide valuable experiences such as knowledge transfer, understanding organizational goals, and workplace culture and values. These experiences lead protégés to feel satisfied with the organization and competent in their job responsibilities, ultimately influencing protégés' effectiveness and identification with the organization. Furthermore, mentorship functions can reduce role conflicts for protégés, enhancing their sense of psychological ownership and fostering positive professional or job attitudes. Employees who have mentorship relationships also tend to experience higher job satisfaction and job commitment. Emphasized the importance of occupational support and sociopsychological support within mentorship functions, highlighting the interaction between learners and mentors. Therefore, it's crucial to focus on social capital that facilitates positive transmission activities between both parties. Furthermore, high-quality mentorship functions tend to make protégés more receptive to the organization's values and goals, making them more willing to invest in the organization and maintain their membership.

Pointed out the significance of mentorship functions in the hotel industry, particularly in influencing job satisfaction and psychological states such as emotions and feelings related to job satisfaction. Additionally, the concept of "Having a place" may help mid-level managers in hotels feel more committed to their organizational roles, generating a sense of psychological ownership in their work and workplace. Therefore, when midlevel hotel managers experience a sense of ownership toward their organization, they are likely to have higher overall job satisfaction, which, in turn, affects their job satisfaction. Based on a prior discussion, the following hypothesis is listed:

H2: Psychological ownership has a significant positive impact on organizational performance.

Psychological ownership moderates the relationship between mentorship functions and organizational performance

Argued that an enhanced sense of psychological ownership is more likely to occur with increased investment of time and effort in ownership goals. This heightened involvement and the sense of impact on their immediate work environment are likely to have positive effects on individuals, including emotional commitment and job satisfaction. Indicated that mentorship functions serve as a powerful strategy to encourage innovation. When organizations establish guiding processes and structures to facilitate creativity, interaction, and communication among new employees, it leads to improved innovation performance. Mentorship functions have a mutual influence on job efficiency, job commitment, and job performance. Mentorship functions can also act as an intermediary through self-efficacy. Mentorship functions not only contribute to the development of feedback between protégés and organizations, resulting in improved organizational outcomes but also assist in enhancing protégés' job skills and performance by effectively transferring richer knowledge and experience. Based on the views of these scholars, this study suggests that mentorship functions can impact organizational performance, psychological ownership can influence organizational performance, and psychological ownership can play a mediating role between mentorship functions and organizational performance. Based on a prior discussion, the following hypothesis is listed:

H3: Psychological ownership exerts an interactive effect on both mentorship functions and organizational performance. Hierarchical regression analysis was employed for data analysis. Therefore, this model serves as the research framework. We presented the research model indicated figure 1 depending on the previous review of the literature and hypotheses (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The conceptual framework.

Sampling and data gathering

This study aims to examine the relationship between psychological ownership, mentorship functions, and organizational performance among new employees who have been in the travel industry for less than one year and are working as tour guides. Typically, newly hired employees in the travel industry are recent university graduates who are filled with aspirations and ideas about the industry. They have a high level of confidence in their ability to perform the duties of tour guides. The questionnaire items were adapted and modified from dividing mentorship functions into "career support," "psychosocial support," and "role modeling" functions, with a total of 18 items. Furthermore, the psychological ownership section was adapted and modified from dividing it into "self-efficacy," "self-identity," and "psychological location," with a total of 19 items. The organizational performance section, on the other hand, was referenced from domestic and foreign scholars such as total of 10 items. The data for this study were collected from new tour guides in the comprehensive travel industry using Google Surveys from February 2021 to September 2022. A total of 200 questionnaires were distributed, with 182 returned, resulting in a response rate of 91%. After filtering, 179 questionnaires were deemed valid, resulting in an effective response rate of 89.5%.

Measurement

The questionnaire used in this study consists of three main sections: The first section collects demographic and basic job information from new tour guide personnel. The second section assesses respondents' perceptions of mentorship functions and psychological ownership concepts. The final section requires respondents to evaluate organizational performance. Additionally, the author collaborated with the human resources departments of comprehensive travel industry companies and managers familiar with the industry to distribute paper surveys and distribute online surveys through tour guide association groups. The survey questions were appropriately modified to suit new tour guide personnel in the comprehensive travel industry and were measured using a fiveconfirm point Likert scale, ranging from "strongly disagree" (1 point) to "strongly agree" (5 points).

Data analysis

This study employed SPSS 20.0 statistical software for various analyses: Descriptive Statistics: The primary purpose of this analysis is to understand the background information of the participants.

Reliability analysis: The most commonly used measure of reliability is Cronbach's α coefficient, which ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher reliability. The data showed that using the factor analysis function in SPSS, multiple factors (latent variables) were extracted, and the maximum factor loading (0.2739) for all variables was less than 0.5. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is no common method variance in the items of this study.

Sample characteristics

Participant demographic information participant demographic data were collected in alignment with the research objectives and included the following variables: gender, age, educational level, monthly income, and years of work experience. Table 1 indicates the profile of the newbies working in the investigated travel agencies. The tour leaders were (i.e., 58.3%) males and (i.e., 41.7%) females. The newbies from 21 to 25 years were the bulk investigated percentage (i.e., 78.8%). The newbies had the most significant 25000˜35000 of monthly income status proportion (i.e., 64.9%), while those who were 35001 above had lower percentages (i.e., 1.4%). Most tour leaders had a university education (i.e., 78.4%) in terms of education. Regarding the length of tour leaders, most newbies had work experience of 4 up to 6 months (i.e., 77.3%) (Table 1).

| Variables | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 58.3 |

| Female | 41.7 | |

| Age | 21˜25 years old | 78.8 |

| 26˜30 years old | 20.6 | |

| 31 years old above | 0.6 | |

| Education | University | 78.4 |

| Graduate school | 21.6 | |

| Monthly income (NT) | 25,000 below | 32.3 |

| 25,001˜35,000 | 64.9 | |

| 35,001 above | 2.8 | |

| Years of work experience | below 3 months | 5.8 |

| 4˜6 months | 77.3 | |

| 7 months above | 16.9 | |

Table 1: Respondents demographic profile (n=301).

Measurement model

The reliability and validity analyses for each scale are as follows: Regarding the mentorship functions questionnaire items, this study utilized and referenced the 18-item scale from. The Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was found to be 0.908, and Bartlett's sphericity test yielded significance (<0.05). The eigenvalues indicated that the items could be divided into two factors, with a cumulative variance of 69.266%. Based on the research mentorship functions can be categorized into two types: instrumental and psychosocial. Therefore, this study also divided them into two factors: Psychosocial: This factor comprises a total of 13 items, and its Cronbach's Alpha value is 0. 955.

Instrumental: This factor consists of 5 items, and its Cronbach's Alpha value is 0. 898. Both factors demonstrate high reliability with Cronbach's Alpha values exceeding the acceptable threshold of >0.7, and the inter-item correlations between questions are >0.5. Regarding the psychological ownership questionnaire items, this study used and referenced the 19-item scale from. The Kaiser- Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was found to be 0.920, and Bartlett's sphericity test yielded significance (<0.05). The eigenvalues indicated that the items could be divided into three factors, with a cumulative variance of 80.100%. This factor is Self-Efficacy: This factor comprises a total of 9 items, and its Cronbach's Alpha value is 0. 959. Self-Identity: This factor consists of 6 items, and its Cronbach's Alpha value is 0. 918. Psychological Having a Place: This factor includes 4 items, and its Cronbach's Alpha value is 0. 873. All three factors demonstrate high reliability, with Cronbach's Alpha values exceeding the acceptable threshold of >0.7, and the inter-item correlations between questions are >0.5.

Regarding the organizational performance questionnaire items, a total of 10 questions were adopted and referenced from the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.874, Bartlett's sphericity test was significant (p<0.05), and eigenvalues greater than 1 were used, with cumulative variance accounting for 65.741%. Cronbach's Alpha value was 0.938, indicating high reliability, exceeding the accepted value of >0.7. Additionally, the inter-item total correlations among the questions exceeded 0.5. The Standard Error of Kurtosis is used to assess normality by examining the ratio of kurtosis to its standard error. If this ratio is less than -2 or greater than +2, it indicates a departure from normality. Positive kurtosis indicates that the tails of the distribution are longer than those of a normal distribution, while negative kurtosis indicates shorter tails, making it resemble a boxy uniform distribution (Tables 2 and 3).

| Variable | Mean | Standard error | Loading | Eigenvalue | Explained variance (%) | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Psychology (SP) | 11.102 | 61.678 | -0.503 | -0.193 | |||

| sp1 | 3.86 | 0.058 | 0.772 | -0.329 | -0.998 | ||

| sp2 | 3.97 | 0.058 | 0.792 | -0.25 | -0.458 | ||

| sp3 | 3.77 | 0.057 | 0.786 | -0.26 | -1.265 | ||

| sp4 | 3.55 | 0.075 | 0.848 | -0.511 | -0.93 | ||

| sp5 | 3.69 | 0.072 | 0.865 | -0.368 | 0.299 | ||

| sp6 | 3.79 | 0.051 | 0.738 | -0.296 | 0.348 | ||

| sp7 | 3.62 | 0.049 | 0.736 | -0.39 | 0.881 | ||

| sp8 | 3.76 | 0.046 | 0.78 | -0.717 | -0.502 | ||

| sp9 | 3.68 | 0.072 | 0.832 | -0.702 | -0.367 | ||

| sp10 | 4.05 | 0.065 | 0.753 | -0.466 | 1.169 | ||

| Instrument | |||||||

| ir1 | 3.98 | 0.062 | 0.721 | 1.366 | 69.266 | -0.58 | -0.487 |

| ir2 | 4.03 | 0.062 | 0.631 | -0.684 | -0.148 | ||

| ir3 | 4.16 | 0.079 | 0.754 | -1.056 | -0.606 | ||

| ir4 | 4.39 | 0.062 | 0.613 | -1.713 | 1.409 | ||

| ir5 | 4.53 | 0.048 | 0.676 | -1.688 | 1.905 | ||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | |||||||

| se1 | 3.45 | 0.063 | 0.82 | 10.629 | 55.943 | -0.259 | -0.881 |

| se2 | 3.88 | 0.053 | 0.884 | -0.359 | -0.002 | ||

| se3 | 3.92 | 0.051 | 0.843 | -0.21 | -0.245 | ||

| se4 | 4.03 | 0.057 | 0.874 | -0.457 | -0.555 | ||

| se5 | 3.36 | 0.088 | 0.839 | -0.368 | -1.135 | ||

| se6 | 3.56 | 0.076 | 0.871 | -0.476 | -0.936 | ||

| se7 | 3.58 | 0.062 | 0.811 | -0.274 | -0.268 | ||

| se8 | 3.63 | 0.058 | 0.852 | -0.091 | -0.228 | ||

| se9 | 3.71 | 0.06 | 0.833 | -0.204 | -0.394 | ||

| Self-identity (SI) | |||||||

| si1 | 2.64 | 0.08 | 0.853 | 3.424 | 73.964 | 0.407 | -1.029 |

| si2 | 2.85 | 0.091 | 0.883 | 0.409 | -1.262 | ||

| si3 | 2.99 | 0.089 | 0.809 | -0.021 | -1.147 | ||

| si4 | 2.86 | 0.073 | 0.792 | -0.072 | -0.871 | ||

| si5 | 3.1 | 0.058 | 0.705 | 0.101 | -0.168 | ||

| si6 | 3.45 | 0.07 | 0.609 | -0.033 | -0.962 | ||

| Having a place (HP) | |||||||

| hp1 | 3.94 | 0.057 | 0.853 | 1.166 | 80.1 | -0.784 | 0.383 |

| hp2 | 3.86 | 0.061 | 0.883 | -0.668 | 0.084 | ||

| hp3 | 3.86 | 0.056 | 0.809 | -0.707 | 0.283 | ||

| hp4 | 2.85 | 0.091 | 0.792 | 0.409 | -1.262 | ||

| Organizational performance (OP) | |||||||

| op1 | 3.55 | 0.075 | 0.772 | 6.574 | 65.741 | -0.26 | -1.265 |

| op2 | 3.98 | 0.062 | 0.792 | -0.58 | -0.487 | ||

| op3 | 4.03 | 0.062 | 0.786 | -0.684 | -0.148 | ||

| op4 | 4.16 | 0.079 | 0.848 | -1.056 | -0.606 | ||

| op5 | 4.53 | 0.048 | 0.865 | -1.688 | 2.905 | ||

| op6 | 4.39 | 0.062 | 0.738 | -1.713 | 2.409 | ||

| op7 | 4.04 | 0.054 | 0.736 | -0.556 | -0.028 | ||

| op8 | 3.68 | 0.072 | 0.78 | -0.717 | -0.502 | ||

| op9 | 3.85 | 0.056 | 0.832 | -0.122 | -0.68 | ||

| op10 | 3.88 | 0.053 | 0.753 | -0.359 | -0.002 | ||

Table 2: Measurement model analysis.

Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis is commonly used across various disciplines to explore the degree of association between two variables, without implying causation. It focuses on the relationship between variables without specifying which one influences the other. Correlation analysis has two key characteristics: magnitude and direction. The magnitude of the correlation coefficient represents the strength of the relationship between two variables and can range from -1 to 1. A correlation coefficient of 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, -1 indicates a perfect negative correlation, and 0 indicates no correlation. The direction of the correlation coefficient indicates whether the variables are positively or negatively related. A positive correlation means that as one variable increases, the other also increases, while a negative correlation means that as one variable increases, the other decreases.

In this study, Pearson's correlation analysis was used to examine the linear relationships between two variables and served as an initial assessment of the strength and direction of the relationships between variables. The results indicate correlations between mentorship functions, psychological ownership, and organizational performance. Factors A to E all show correlations with organizational performance (Table 3).

| Variable | Sub-Variables | A | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentoring functions | A: Social Psychology | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B: Instrument | 0.601** | ||||||

| Psychological ownership | C: Self-Efficacy | 0.568** | 0.603** | ||||

| D: Self-identity | 0.614** | 0.299** | 0.176** | ||||

| E:Having a place | 0.879** | 0.537** | 0.581** | 0.313** | |||

| Organizational performance | F: OP | 0.687** | 0.761** | 0.749** | 0.255** | 0.283** |

Note: **. Significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed)

*. Significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed)

Table 3: Pearson correlation coefficients among variables.

Regression analysis

The regression analysis conducted in this study aimed to examine the relationships between mentorship functions, psychological ownership, and organizational performance. The analysis yielded the following results:

Model 1: The inclusion of the two sub-constructs under the mentorship function dimension as explanatory variables resulted in an R-squared (R2) value, representing the coefficient of determination. An increase in R2 indicates improved explanatory power of the regression model. In Model 1, only the "Psychosocial" sub-construct significantly influenced "Organizational Performance" (with a regression coefficient of 0.478 and significance). This implies that Hypothesis H1, which posits a significant positive impact of mentorship functions on job performance, is supported.

Model 2: When the "Psychological Ownership" variable was added to the model, it contributed to a significant increase in the overall explained variance of "Organizational Performance" (△R2=0.015, positive and significant). This suggests that the inclusion of the "Psychological Ownership" variable was meaningful. Among its sub-constructs, "Self-Efficacy" significantly influenced "Organizational Performance" (with a regression coefficient of 0.274 and significance), as did "Self-Identity" (with a regression coefficient of 0.024 and significance). However, the "Psychological Location" sub-construct had a significant negative impact (with a regression coefficient of -0.033 and significance) on "Organizational Performance." Thus, Hypothesis H2, indicating a significant positive impact of psychological ownership on organizational performance (except for the sub-construct "Psychological Location," which has a negative impact), is supported.

Model 3: The most critical finding was that, after including the interaction terms between "Mentorship Functions" and "Psychological Ownership" in Model 3, there was a further significant increase in the overall explained variance of "Organizational Performance" (△R2=0.001, positive and significant). This result suggests that the interaction terms have a significant impact on the organizational performance of new tour guides in the travel industry. Consequently, it implies that psychological ownership can indeed moderate the relationship between mentorship functions and organizational performance (Table 4).

| DV | Organizational performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IV | M-1 | M-2 | M-3 |

| IV: Mentorship relationship | |||

| Social psychology | 478*** | 0.261*** | 0.260*** |

| Instrument | 0.568*** | 0.558*** | 0.555*** |

| Moderating variables: Psychological ownership | |||

| Self-efficacy | - | 0.274*** | 0.275*** |

| Self-identity | - | 0.024* | 0.025* |

| Having a place | - | -0.033* | -0.034* |

| Interaction term | |||

| MR * PO | - | - | -.004* |

| R2 | .968*** | 0.983 | 0.984 |

| △R2 | 0.968 | 0.015 | 0.001 |

| △F | 3680.970*** | 73.223*** | .114*** |

Note: *p<0.05; *** p<0.001; Mentorship Relationship (MR); Psychological Ownership (PO)

Table 4: Hierarchical regression analysis.

Demographic variable tests: Independent sample t-tests, one-way Anova tests

In this study, various tests were conducted to examine the impact of demographic variables on organizational performance:

Gender: An independent sample t-test was performed to assess gender differences in organizational performance. The Levene test for equal variances yielded an F-value of 1.894 with a p-value>0.05, indicating that gender differences did not produce significant variations in organizational performance (t-value=0.46, degrees of freedom=216, p-value>0.05).

Education: Another independent sample t-test was conducted based on respondents' education levels. It was found that respondents with educational backgrounds ranging from college to postgraduate levels did not exhibit significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=0.916, p-value>0.05).

Monthly income: One-way ANOVA was applied to examine the impact of monthly income on organizational performance. The analysis showed that different income groups among respondents did not lead to significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=1.886, p-value>0.05).

Year of work experience: One-way ANOVA was used to assess the influence of work experience on organizational performance. The results indicated that varying levels of work experience among respondents did not result in significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=0.941, p-value>0.05). In summary, demographic variables including gender, age, education level, monthly income, and work experience did not have a significant impact on organizational performance according to the statistical tests conducted in this study.

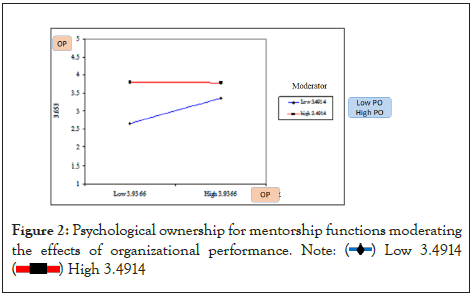

Notably, the interaction terms between "Mentorship Functions" and "Psychological Ownership" had a significant negative impact on "Organizational Performance." This indicates that the influence of mentorship functions on organizational performance is stronger in cases of lower psychological ownership. In other words, when employees in the travel industry have lower psychological ownership, it is crucial to pay more attention to the degree of psychological ownership they possess, as this can effectively enhance employee organizational performance (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Psychological ownership for mentorship functions moderating

the effects of organizational performance. Note:  Low 3.4914

Low 3.4914

High 3.4914

High 3.4914

In this study, various tests were conducted to examine the impact of demographic variables on organizational performance:

Gender: An independent sample t-test was performed to assess gender differences in organizational performance. The Levene test for equal variances yielded an F-value of 1.894 with a p-value>0.05, indicating that gender differences did not produce significant variations in organizational performance (t-value=0.46, degrees of freedom=216, p-value>0.05).

Education: Another independent sample t-test was conducted based on respondents' education levels. It was found that respondents with educational backgrounds ranging from college to postgraduate levels did not exhibit significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=0.916, p-value>0.05).

Monthly income: One-way ANOVA was applied to examine the impact of monthly income on organizational performance. The analysis showed that different income groups among respondents did not lead to significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=1.886, p-value>0.05).

Year of work experience: One-way ANOVA was used to assess the influence of work experience on organizational performance. The results indicated that varying levels of work experience among respondents did not result in significant differences in organizational performance (F-value=0.941, p-value>0.05). In summary, demographic variables including gender, age, education level, monthly income, and work experience did not have a significant impact on organizational performance according to the statistical tests conducted in this study.

Tests of interaction effects

Based on the observations from Figure 2, the graphical representations of high and low levels of psychological ownership exhibit discernibly divergent trends. These non-parallel trajectories suggest that varying levels of psychological ownership introduce an interfering influence within the relationship between mentorship functions and organizational performance. Additionally, we conducted a simple slope analysis, as per the conceptual model, to elucidate the direction of the interaction effect and discern disparities between the regression lines pertaining to high and low psychological ownership.

The graphical representation illustrates the outcomes of the simple slope analysis involving psychological ownership in the mentorship functions-organizational performance relationship. It becomes apparent that across distinct levels of psychological ownership, the magnitude of the positive impact, as represented by the slope, significantly fluctuates. Notably, the slope associated with low psychological ownership surpasses that of high psychological ownership, signifying a more pronounced effect of mentorship functions on organizational performance when psychological ownership is lower.

Notably, the interaction term denoted as "Mentorship Functions*Psychological Ownership" exerts a statistically significant negative influence on "Organizational Performance." This indicates that the effect of "Mentorship Functions" on "Organizational Performance" is amplified when psychological ownership levels are lower. In essence, when employees demonstrate reduced psychological ownership within the travel industry, it becomes imperative to prioritize interventions aimed at adjusting their psychological ownership. This adjustment, in turn, leads to a more pronounced positive impact on other employees within the organization. Such measures are of paramount importance in effectively enhancing overall organizational performance.

In summary, the analysis unveils that in instances where employees exhibit lower levels of psychological ownership, the influence of "Mentorship Functions" on organizational performance is notably more significant when contrasted with scenarios characterized by higher psychological ownership. This implies that within the context of the travel industry, particularly when new employees manifest reduced psychological ownership, the pivotal role of "Mentorship Functions" gains heightened prominence. In contrast to prior studies predominantly emphasizing the favorable impact of "Mentorship Functions" on "Organizational Performance," this research contributes a deeper comprehension by examining the dynamics of low psychological ownership in the management of the travel industry.

In the realm of comprehensive tourism management, tour leaders assume a critical role in the successful execution of travel-related activities. This study underscores the substantial impact of mentorship functions on the development of these tour leaders. Through a thorough literature review and meticulous result analysis, it becomes increasingly clear that the extent of psychological ownership, particularly among newly graduated tour leaders entering the travel industry, can have significant implications for the organizational performance of travel companies. This discovery implies that newbies, armed with fresh academic knowledge, may not always readily embrace guidance from their more experienced colleagues, potentially leading to integration challenges within the organization.

Furthermore, these findings highlight the need for a structured mentorship system within the travel industry, one that can effectively bridge the gap between seasoned professionals and new entrants. Such a system would facilitate the seamless transfer of knowledge and expertise, fostering better collaboration and ultimately enhancing organizational performance.

Theoretical implications

In Taiwan's travel industry, professionals are required to obtain government-issued licenses or certifications from relevant associations, such as tour guides or tour leader licenses, to conduct their work. These licenses are essential for ensuring the quality and professionalism of services provided within the industry. However, the performance of these professionals is not solely dependent on their qualifications; it is also significantly influenced by the leadership style and directives of their travel agency leaders. Effective leadership plays a crucial role in guiding and motivating travel industry professionals to excel in their roles.

Moreover, the implementation of mentorship programs has gained recognition as a valuable strategy for fostering talent development in the travel industry. Mentorship provides a platform for experienced professionals to share their knowledge and insights with newbies, facilitating their growth and integration into the field. However, despite the strong endorsement of mentorship systems, the absence of strict regulations and clear guidelines poses challenges. The lack of a standardized mentorship framework may hinder the full realization of the potential of mentorship functions, particularly in the context of training and nurturing tour leaders.

Furthermore, it's essential to address the needs and concerns of experienced tour leaders, including issues related to compensation and allowances. Providing fair and competitive compensation packages can help retain and motivate these seasoned professionals, ensuring their continued commitment to delivering high-quality travel experiences. As travel agencies aim to enhance travel quality, customer loyalty, and reduce complaints, talent development, including the implementation of effective mentorship programs, emerges as a vital strategy. By investing in the competence and professional growth of frontline tour leaders, travel agencies can better achieve their objectives and maintain their competitiveness in the industry.

Formal mentorship programs: The study highlights the paramount importance of implementing formal mentorship programs within organizations operating in the tourism and hospitality industry. These programs can serve as a powerful tool for facilitating knowledge transfer and skill development among new tour leaders. By establishing structured mentorship systems, companies can bridge the experience gap and ensure that newbies integrate smoothly into the industry. This approach not only accelerates the learning curve of new team members but also contributes to enhanced organizational performance.

Fostering psychological ownership: Organizations should be attuned to the varying levels of psychological ownership among their new tour leaders, particularly those who are recent graduates entering the workforce. To optimize performance and engagement, managers can invest in strategies aimed at enhancing psychological ownership from the outset of these individuals' careers. Creating an environment that instills a sense of ownership and responsibility can lead to increased commitment and dedication among team members, ultimately benefiting the organization.

Supporting experienced professionals: Recognizing and addressing the compensation and professional development needs of experienced tour leaders is crucial for talent retention. Competitive compensation packages and opportunities for career growth are essential to motivate and retain these seasoned professionals. By retaining the expertise of experienced tour leaders, organizations can ensure a consistent level of excellence and a positive impact on organizational performance. Additionally, fostering a culture of continuous learning and collaboration by encouraging knowledge sharing and open communication between tour leaders and mentors can maximize the effectiveness of mentorship functions, benefiting both individual career development and organizational success.

In summary, this study's managerial implications emphasize the importance of formal mentorship programs, psychological ownership dynamics, and the support of experienced professionals in the tourism and hospitality industry. Implementing these strategies can lead to improved organizational performance, enhanced customer experiences, and sustained competitiveness in a dynamic and evolving sector.

In the pivotal role of tour leaders in comprehensive travel management cannot be overstated. Their successful integration into the industry hinges on the effectiveness of mentorship functions, particularly in navigating the complexities of psychological ownership among new entrants. The research employed a comprehensive approach, including questionnaire development and data analysis. By recognizing and addressing these dynamics, travel companies can improve their organizational performance and ensure the continued growth and success of their teams.

This study has certain limitations. The sample size, reliant on selfreport surveys, may limit generalizability. The cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality, and the findings' context specificity should be noted. Future research can address these limitations by employing larger and diverse samples, longitudinal designs, and more objective measures. Further research avenues include comparative analyses across industry sub-sectors, intervention studies to evaluate mentorship programs, qualitative research for deeper insights, and strategies to enhance psychological ownership. Expanding organizational performance metrics and conducting cross-cultural studies would offer a more comprehensive perspective. These steps will advance our understanding and contribute to the broader discourse in the field.

[Cross Ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref ] [Google Scholar]

Citation: Chang NW, Liu CH (2023) The Impact of Mentoring Functions on Organizational Performance: The Moderating Effect of Newbie Tour Leaderâ??s Psychological Ownership. J Tourism Hospit.12:531

Received: 29-Sep-2023, Manuscript No. JTH-23-27264; Editor assigned: 02-Oct-2023, Pre QC No. JTH-23-27264 (PQ); Reviewed: 16-Oct-2023, QC No. JTH-23-27264; Revised: 23-Oct-2023, Manuscript No. JTH-23-27264 (R); Published: 30-Oct-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0269.23.12.531

Copyright: © 2023 Chang NW, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.