Poultry, Fisheries & Wildlife Sciences

Open Access

ISSN: 2375-446X

ISSN: 2375-446X

Review Article - (2021)Volume 9, Issue 11

The global seafood industry generates significant amounts of waste, consisting of low value by-catch and processing discards, which include shell, head, bone intestine, fin, skin, etc. besides voluminous amounts of nutrient-rich wastewater as process effluents. These discards and effluents, if not properly valorized, are responsible for heavy losses of valuable nutrients as well as for serious environmental hazards. The problems can be addressed by valorization of the waste by environmentally savvy green processes. These generally involve bioconversion based on microbial fermentation or action of externally added enzymes, which release the ingredients from the food waste matrices. The released nutrients, biomaterials, industrial chemicals and also bio-energy are isolated by appropriate green processes. Cultivation of microalgae in seafood waste generates algal biomass, as single cell proteins (SCP), which are rich sources of proteins, oil, polysaccharides, bio-energy and others. A bio-refinery approach for multiple components recovery is economically viable that can contribute towards a sustainable bio-economy.

Seafood discards; Process effluents; Cleaner production; Valorization; Green technology; Bio-refinery

Food security is very much dependent on the sustainable availability of nutritious and safe food. Fisheries and aquaculture, which are major components of international food trade, significantly contribute to nutrition, food security and possibly to poverty alleviation [1]. However, burgeoning world population, climate change, ocean acidification, global warming and the current pandemic are showing strains on the availability of marine resources. In the year 2018, an amount of 178.5 Million Tons (MT), consisting of 96.4 MT of capture fisheries and 82.1 MT of aquacultured items were harvested [2]. The popular seafood items belong to finfish (pelagic, anchoveta, pollock, tuna, herring, mackerel, whiting, and others), and shellfish, which can be crustaceans such as shrimp, krill, crab, lobster, and, mollusks, consisting of bivalves (mainly mussels, oysters, clams, and scallops), cephalopods (squid and cuttlefish), and gastropods (mainly abalone, snails). Unfortunately, the fish stocks that are within biologically sustainable levels have decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 65.8 percent in 2017 [2]. Furthermore, more than a quarter of marine fish stock is over-fished and the rest increasingly fished at their maximum capacity [3]. In addition, all the available catch does not fetch value as food. A sizeable portion of the harvest, designated as by-catch, although rich in nutrients, have poor consumer acceptance due to unappealing appearance, smaller size and other reasons. Besides, commercial processing of valuable fishery items including shellfish results in discards consisting of shell, head, bones intestine, fin, skin etc., as high as 50%, depending on the raw material. It has been estimated that on an average, about 40% of seafood produced globally is wasted. Annually about 6 to 8 million tons of shell waste from crab, shrimp and lobster are produced globally [4]. On dry weight basis, the finfish wastes have approximately 60% proteins, 19 to 20% fat, and 20 to 21% ash. Wet crustacean shells contain 20 to 40% protein, 20% calcium carbonate and other minerals including magnesium salts and 15 to 20% chitin. Fishery wastes are rich in nutrients including functional proteins, enzymes, gelatin, collagen, peptides, carotenoids, oil rich in long chain omega n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (omega-3 PUFA), minerals and others such as chitin, chitosan, glucosamine, etc. Loss of these nutrients denies nutrition to millions all over the world [5,6]. Besides, washing, boiling, filleting, marination and other operations consume as high as 10 to 40 m3 freshwater per ton of the raw material; the process effluents contain significant quantity of proteins and other nitrogenous compounds, Fats, Oils, and Grease (FOG), in soluble, colloidal, or particulate forms as Total Suspended Solids (TSS), which are responsible for high Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) [7]. Disposal of by-catch through ocean dumping can damage the oceanic ecosystem, while landfill causes formation of hazardous gases such as methane, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide. The environmental issues of seafood processing include high consumption of water, generation of effluent streams, consumption of energy and the generation of discards [8,9]. In addition, shortage of drinking water, eutrophication (growth of unwanted biota), biotic depletion, algal blooms, and extensive siltation of corals are other environmental hazards [7]. The above situation warrants that the seafood industry should make sufficient efforts not only to maintain sustainability of the resources but also to control the industry-related environmental hazards. It has been recognized that if global fisheries were optimally managed, it would generate an additional US $50 billion as income [3].

There is urgent need to significantly reduce global food waste and post-harvest food losses along the production and supply chains to achieve the sustainable development goal target 12.3 of the United Nations by the year 2030 [2]. It is well recognized that a circular economy can strengthen resource efficiency and reduce the use of additional fossil carbon. In a circular economy, the value of products, materials and resources is maintained for as long as possible and the generation of waste is minimized. Bioeconomy, like circular economy, has similar concepts, which aim at improved resources and eco-efficiency, lower Greenhouse Gases (GHGs) emission, reduce the demand of fossil carbon, and valorize waste and side streams. Bio-economy relies on biotechnology for valorization of waste biomass including waste streams into value added products such as nutritious food, feed, bio-based food supplements, functional ingredients, healthy animal feeds and bioenergy. Biotechnological approaches avoid or make lower uses of toxic and harsh chemicals. Circular bio-economy, which is defined as an intersection of circular economy and bio-economy, aims at utilization and up gradation of organic wastes, thereby significantly resolving food-related global issues [10]. Depletion of fishery resources, their incomplete utilization, generation of nutrient-rich waste biomass and effluents as well as their role in environmental degradation are the major seafood-related global issues. Many of these issues can be significantly addressed by circular bio-economy processes. These essentially rely on the concepts of ‘reduce, reuse and re-cycle’ for the recovery of renewable biological resources including food, food supplements, functional ingredients, healthy animal feed, and bioenergy from food waste biomass and process effluents [11-13]. These approaches are compatible with the European Bio-economy Strategy (2012), which reconciles food security with the sustainable use of renewable resources, while ensuring environmental protection [10].

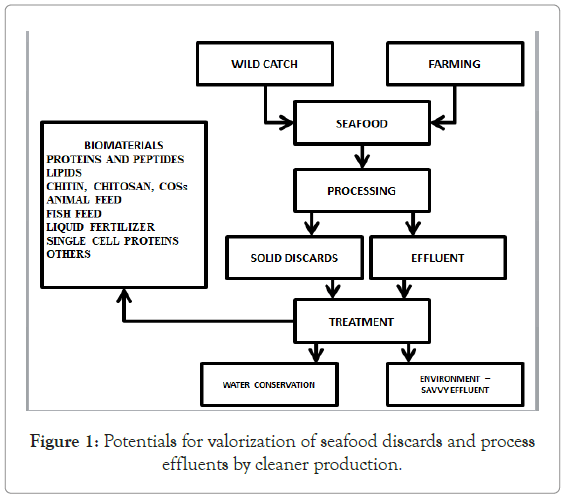

It is therefore important that the seafood discards and effluents are properly treated by biotechnological processes to achieve the objectives of bio-economy. Conventional processes for the valorization of seafood waste and waste streams are based on chemical and physical methods, which have several limitations and, therefore cannot be used indiscriminately [14]. For example, acid and alkali treatments of crustacean shell waste for chitin extraction require large volumes of freshwater to wash off alkali and acid, releasing corrosive waste water. Similarly, the chemical production of Chitosan Oligosaccharides (COSs) is environmentally hazardous and also difficult to control the degree of polymerization and acetylation. Solvent extraction of lipids from fishery waste can cause oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids [13-15]. Therefore cleaner production methods are required for waste treatment. Cleaner production is defined as continuous application of an integrated preventive, environmental strategy applied to products, processes and service [8]. These biotechnology-based green processes employ processing pathways use less harsh chemicals to achieve the objectives of bio-economy. They are environmentally friendly, cost effective and safe and have potential to convert food waste and wastewater into valuable raw materials thereby satisfying the objectives of sustainable seafood processing and ‘water-energy-food nexus [11,15-19]. Figure 1 depicts potentials for the recovery of valuable ingredients from bioprocessing of seafood discards and effluents. This article briefly points out potentials for environmentally friendly green processes for bioprocessing of seafood discards and effluents that can have achieve the objectives of bio-economy.

Figure 1: Potentials for valorization of seafood discards and process effluents by cleaner production.

Valorization of seafood waste essentially depends on its initial bioconversion to release the components from the food matrices followed by extraction of ingredients from the treated materials. The choice of the green processes depend on the nature of the food matrices and the chemistry of the targeted compounds [6,17,18,20,21]. For example, iso-electric pH solubilization precipitation, which is a pH shift process and weak acid-induced gelation are plausible green methods for the recovery of proteins from fishery discards [22].

Bioconversion by microorganisms

Growth of microorganisms in food waste helps bioconversion, providing safe and effective release of components from the food matrices [18,21,23]. Fermentation by suitable microorganisms (aerobic, anaerobic, or facultative bacteria, fungi, mycelium, or microalgae) results in the production of hydrolytic enzymes such as proteases, chitinases and lipases, and others depending on the microorganism. Proteases replace alkali in the conventional treatment for proteolysis, assisting deproteination and demineralization of the waste. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) dependent bioconversions make otherwise inedible foods edible, nutritional, less toxicity, preserve, and decrease cooking time. LAB-fermentation breaks down sugar to lactic acid, resulting in pH as low as 3.5; the low pH helps optimal activity of enzymes such as acid proteases, which release proteins bound to lipids, carbohydrates, minerals and carotenoids in the waste. The acid also reacts with calcium carbonate, the main mineral component to form calcium lactate resulting demineralization of the shells and also controls growth of contaminant microorganisms [14]. Chitinases catalyze the cleavage of the β-1,4-O-glycosidic bonds in chitin. Lipases function as triacylglycerol hydrolases and also catalyze the synthesis of ester compounds. The fermentation processes can be batch or fed batch types operated under solid, submerged, liquid, or anaerobic conditions. In the commonly used fed-batch process the culture medium is added continuously or in pulses to reach the optimal volume in the reactor. The advantages of fed-batch over the conventional batch operation are higher productivity and decrease in fermentation time. Solid state fermentation of fish offal in presence of sawdust and wood shavings in equal proportions gave a nutritive fertilizer [24]. Microbe-assisted aerobic bioprocess of fishery waste including aquaculture solid waste resulted in bioconversion of nitrogen into ammonium ions [25].

Microbial fermentation processes are highly desirable due to easy handling, simplicity, rapidity, controllability through optimization of process parameters, and negligible requirements of organic solvents. Fermentation is safe, environmental-friendly and low energy consuming. Bio-extraction of chitin is emerging as a green, cleaner, eco-friendly and economical process. Fermentation increases the quality of protein hydrolysates, oil, chitin and produces antioxidant compounds [17,26]. Successful pilot production of chitin using LAB fermentation process has been reported in the early 2000s. The epiphytic Lactobacillus acidophilus isolated from shrimp waste was used to ferment shrimp waste on a pilot scale. The pH of the fermentation broth decreased to a value as low as 3.99 after 12 hr. Besides, the high protease activity of the LAB helped quick removal of minerals and protein. The residue of the fermented shrimp waste contains less than 1% minerals and can be easily transformed into chitin by a mere bleaching treatment [27]. Fermentation by Bacillus megaterium and B. subtilis recovered chitin along with protein hydrolysate from prawn shell waste [28]. Chitosan is a versatile compound having diverse uses. Production of high viscosity chitosan from biologically purified chitin isolated by microbial fermentation has been reported [29]. Protein hydrolytes and calcium lactate are by-products that are useful for animal feed and calcium supplements [4]. Fish viscera may contain 19 to 21 lipids; up to 85% of the lipids could be recovered by fermentation [30]. Several microbial bioconversion processes for seafood waste valorization have been discussed recently [6].

The conversion of food waste including seafood discards into algal biomass resource has attracted attention as a green and economically viable process to recover functionally active compounds. This makes use of cultivation of microalgae such as chlorella, spirulina, dunaliella, diatoms, and cyanobacteria (blue green algae) in the nutrient rich waste in open ponds, under heterotrophic conditions or in closed photo-bioreactors. Growth of these organisms allows degradation of organic contents, and unused food with the removal of CO2, NH3-N, CO2, and H2S, thereby reducing environmental pollution. The cultivated algal biomass referred as single cell proteins (SCP) can contain up to 60% proteins, good amounts of oil, and also polysaccharides, minerals, carotenoids, and other biomaterials. These ingredients can be extracted from SCP by suitable means. The algal technology has good scope to develop proteins, oil, bioactive peptides, plant growth stimulants, aqua-feeds, food additives, cosmeceuticals, and others [31,32]. Cultivation under stringent nitrogen limitations stimulates the algae to produce lipids as high as 75% rich in n-3 PUFA. Microalgae have the key advantage to produce third generation biofuel (bioethanol, biobutanol, and biogas), because of its rapid growth associated with high lipid production [33]. Chlorella vulgaris accumulated a lipid content of 32.15 ± 1.45% when cultivated in seafood effluent [34]. Algal products are nutritious and generally safe to human, animals and plants. For instance, spirulina, having 60 to 71% proteins, 13 to 16 carbohydrates and 6-7% fat, is emerging as an effective nutrient to improve poultry productivity [35]. Table 1 gives examples of microbial bioconversions for resource recovery from seafood processing waste.

| Seafood discards | Microorganism | Products |

|---|---|---|

| Shell waste | Lactic acid bacteria | Calcium, carotenoids peptides |

| Shell waste | S. marcescens | Chitinases, proteases, pigment |

| Shrimp waste | L. acidophilus | Chitin, protein hydrolyzate |

| Shrimp head | Lactic acid fermentation | Chitin and aquafeed |

| Shrimp waste | P. acidolactici | Carotenoids |

| Shrimp waste | B. cereus and E. acetylicum. | Chitin, protein |

| Prawn shell waste | B. megaterium, B. subtilis | Chitin, protein hydrolysate |

| Shrimp waste | Solid state fermentation by L. brevis and R. oligosporus | Chitin |

| Crab shell waste | L. paracasei, and S. marcescens | Chitin |

| Fish waste | Mixed microorganisms | Liquid fertilizer |

| Seafood effluents | Microalgae | Single cell protein [SCP] |

| Mussel processing effluents | S. zooepidemicus fermentation | Hyaluronic acid |

| Aquaculture solid waste | Aerobic microbial bioconversion. | Liquid fertilizer |

| Tuna waste | L. plantarum, B. licheniformis | Aquafeed |

| Fresh water fish viscera | P. acidilactici | Oil |

| Grass fish bone | Proteolysis and LAB [L. mesenteroides] fermentation | Calcium supplement |

| Tuna condensate | Candida rugosa and .L. futsaii | Glutamic acid, gamma aminobutyric acid |

Table 1: Examples of resource recovery by microbial bioconversions of seafood processing waste.

Bioconversion by enzymes

Enzymes can be used as additional processing aids to conventional processes Bioconversions using exogenous enzymes cause direct releases of the components from the food matrices. Hydrolases such as carbohydrases, proteases, and lipases are popular enzymes used for this purpose. The advantages of enzymes are their low energy requirements, safety, and low cost [36]. Chitinases have gained recent biotechnological attention due to their ability to transform chitin in biological waste COSs having wide agricultural, industrial or medical applications. Chitinase Chit42 was expressed in a heterologous system. The enzyme produced small partially acetylated COSs, which have enormous biotechnological potentials in agriculture, medicine and food. Chitosanases are glycosyl hydrolases that catalyse the endohydrolysis of β-1,4-glycosidic bonds of partially acetylated chitosan to release COSs [37-39]. Enzymatic hydrolysis and bacterial fermentation of heads and other discards of several fish species, followed by green extraction processes, recovered Fish Protein Hydrolysates (FPHs), peptones and PUFA-rich oils. The FPHs, having a degree of hydrolysis of more than 13% and soluble protein concentrations greater than 27 g/L, had good antioxidant and antihypertensive activities. The peptones were viable alternatives to expensive commercial ones [40]. The enzyme, alcalase extracted 26% high quality oil from salmon heads and frames [41]. A few examples on the uses of enzymes for the recovery of various ingredients from diverse fishery wastes are pointed out in Table 2.

| Seafood discards | Enzyme | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Shrimp heads | Brevibacilluys sp. alkaline protease | Chitin |

| Crab and shrimp shells | Deproteination by crab protease | Chitin |

| Shrimp shell | Proteases | Protein, chitin, carotenoprotein |

| Shrimp shell | Chitinases, chitosanases and chitin deacetylases | Better defined chitosan and chitosan oligomers |

| Lobster waste, shrimp waste |

Papain, bacterial protease, alcalase, pancreatin |

Astaxanthin |

| Crude chitin | Chitinase | Chitin oligomers, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine |

| Fin, head, scales | Collagenase, trypsin | Collagen |

| Fish waste | Proteases | Fish protein hydrolysate |

| Salmon frame | Proteases | Oil, peptides |

| Salmon heads | Proteolysis, lipase | PUFA-rich oil |

| Fish oil | Candida rugosa lipase | PUFA-rich oil |

| Tuna head | Alcalase | Deodourized oil |

| Fish bone | Intestine crude proteinase | Bone oligo-phospho-peptide |

Table 2: Examples of resource recovery by enzymatic bioconversions of seafood discards.

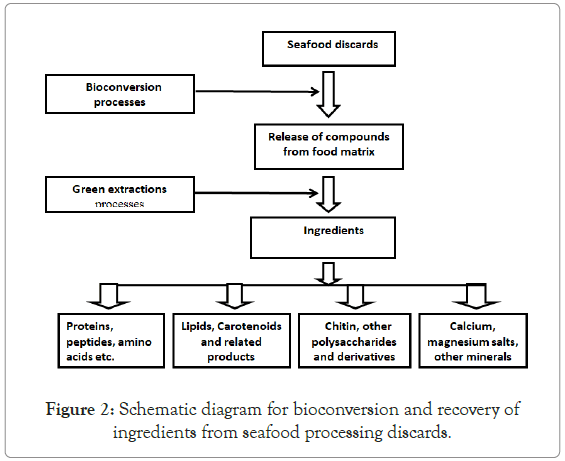

The compounds released by microbial or enzymatic bioconversion processes can be isolated and concentrated by coupling the bioconversion processes with suitable biotechnology-based green innovative processes, which are generally mild, cost-effective, safe, and environmental friendly. They mostly involve reduced process time along with enhanced yields of products. These processes include ultrafiltration, nano-filtration pressurized liquid, subcritical, super-critical fluid, enzyme-mediated, microwave and ultrasound-assisted extractions, and others [18,20,42,43]. LAB fermentation followed by green extraction processes can help sequential or simultaneous recovery of astaxanthin, hydrolyzed protein and chitin from crustacean waste [44]. Green methods are available for fish oil extraction; one of the promising methods is supercritical CO2 extraction [45]. A sulfated polysaccharide fraction having anticoagulant activity was isolated from the gonads of abalone by enzymatic hydrolysis followed by ion-exchange and gel-filtration chromatography [46]. Bioactive compounds from lobster processing by-products can be extracted using microwave, ultrasonic, and supercritical fluid extraction [47]. Pre-treatment by ultrasonication and microwave radiation improved extraction of chitin by fermentation or chemical routes [38]. Hydrothermal conversion (including hydrothermal liquefaction and hydrothermal carbonization), is a cost-effective and environmentally friendly thermo-chemical technology for the utilization of biomass as sources of biochar and bio-oil [48] Hydrothermal treatment followed by enzymatic hydrolysis recovered about 85% protein from tilapia scales, giving a gelatin hydrolysate containing peptides in the range of 200-2000 Da. The peptide fraction had stable Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity [49]. Membrane bioreactors integrate reaction vessels with membrane separation units for producing materials such as peptides, COSs and PUFA from seafood discards [50]. Advancements of waste valorization by biotechnological conversion processes have been discussed [51]. Figure 2 depicts general process for extraction of various ingredients from seafood waste biomass through bioconversion and green methods.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram for bioconversion and recovery of ingredients from seafood processing discards.

The voluminous amount of process effluents is a burden to the seafood industry, as pointed out earlier. The major advantages of effluent treatment are alleviation of environmental hazards, conservation of water, and recovery of commercially valuable ingredients. Biological treatments of effluents make use of aerobic, anaerobic or facultative microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa to degrade organic matter present in the waste water. Fermentation of seafood wastewater by organisms such as Saccharomyces sp. and Lactobacillus plantarum in presence of molasses can give a stable product that could be used as feed. Membrane processes are novel cost-effective. These have been discussed in detail [9]. The aquaculture industry is one of the fastest growing sectors in food production and consumes volumes of water for fish farming operations. Discharge of the untreated waste water is highly harmful to the environment. The treatment options for aquaculture effluents include sedimentation, filtration, and mechanical separation, chemical and biological treatments. Electrochemical Oxidation (EO) has potential to treat aquaculture wastewater for removal of multiple pollutants. The EO process has also good bactericidal effect and can remove antibiotics in the effluents [52]. Industrial level treatments of effluents and opportunities, challenges, and prospects of recovery of resources particularly by biological technologies have been discussed in detail [9,53]. Table 3 summarizes some of the green processes for effluent treatment.

| Process | Advantages |

|---|---|

| Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) | Reduce sedimentation time of suspended solids, BOD and COD |

| Activated sludge consisting of mixed microorganisms | Degrades organic materials in presence of dissolved O2. Removes nutrients and heavy metals. Reduction in BOD, COD, Saves water. |

| Anaerobic digestion | Involves hydrolysis, liquefaction, and fermentation in the absence of O2. Gives methane for energy use. |

| Membrane processes: microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), nanofiltration (NF), reverse osmosis (RO), forward osmosis (FO). Can be integrated with biological methods |

Can efficiently separate organic matter consisting of proteins, bacteria, viruses, etc. The COD and NH3-N removal efficiency of the system can be as high as 95%. |

| Electrochemical oxidation | Removes proteins, lipids etc. Potential to treat aquaculture wastewater |

| Cultivation of microalgae in systems such as photobioreactors to give SCP | SCP is source of various biomaterials. Lipids of SCP can be converted into biofuels. |

| Flocculation by electro-flocculation or by flocculants such as chitosan, carrageenan, alginate, carboxymethyl cellulose, etc. | Sedimentation of proteins and other materials, which can be recovered by membrane processes. Useful for aquaculture water treatment. |

| Microbial fuel cell | COD reduction, source of energy. |

Table 3: Some green processes for the treatment of seafood process effluents.

The ingredients isolated from seafood waste biomass can have diverse commercial uses [22,23]. The effluents can also be subjected to multiple processes for the isolation of biomaterials including proteins, peptides, amino acids, oil, and others [6,9]. Proteins including collagen and also gelatin isolated from seafood discards as well as effluents invariably retain their natural functional properties including solubility, water-holding, emulsion capacity, antioxidant activities, among others. They can be used as additives including emulsifiers, and texturizers. Protein hydrolysates can function as bio-stimulants for improvement of plant growth, chlorophyll synthesis and as sources of peptides for use as antioxidants, antimicrobials and other functional additives [22]. Lipids are rich in PUFA and therefore can be food additives. Fish oil, when subjected to ozonization and trans-esterification can be source of bio-energy, while carotenoids are natural antioxidants and food colorants [9]. Chitin and other polysaccharides can have diverse industrial and pharmaceutical applications. Applications of ingredients isolated from various seafood discards and effluents have been discussed [6,9].

Most individual extraction processes of components from seafood waste and effluents, as pointed out earlier, may have limitations with respect to their economical viabilities. Therefore, recovery of multiple compounds through a cascade of processes based on an integrated bio-refinery approach (defined as ‘sustainable processing of biomass into a spectrum of bio-based products) has received recent attention. A successful seafood bio-refinery can have lower operation costs and lower energy consumption, along with high productivity. The bio-refinery allows zero discharge of nutrients from both solid wastes and effluents [54]. The European Commission has opined that these bio-refineries should adopt a cascading approach that favors the highest volume of value added and resource efficient products [10]. Bio-refinery can convert fish waste material into value added biological products such as biofuels, industrial chemicals, animal and fish feed, human food, neutraceuticals and organic fertilizer, etc., [55]. A typical example is the shell refinery where crustacean can be subjected to fermentation, sequential enzymatic, and other processes to recover chitin, proteins including collagen and gelatin, protein hydrolyzates, peptides, PUFA-rich lipids, carotenoids, calcium carbonate, chitin, and chitin oligosaccharides, sulfated and amino-polysaccharides and N-acetylglucosamine [4,56]. Algal biotechnology can be a promising platform for bio-refining of seafood discards on a commercial scale [57]. Cultivation of oleaginous microorganisms including microalgae, yeasts, and bacteria helps valorization of organic wastes for energy production [58,59]. Wastewater treatment incorporating microalgae culture could be greatly developed in the future to achieve a greener environment [34]. The bio-refinery approach can also be extended to make better use of low-cost bycatch fish. Successful pilot plant studies in valorization of seafood waste biomass and effluents including using algal technology have been summarized recently [6,9]. Table 4 gives some examples of bio-refinery based seafood waste treatment. Advances in genetics, biotechnology, process chemistry, and enzyme engineering can further improve the bioconversion and bio-refinery strategy, which can further achieve the objectives of bio-economy [54].

| Bio-refinery | Products having various uses |

|---|---|

| Algal bio-refinery, Cultivation of alga, Haematococcus pluvialis | Astaxanthin, SCP |

| Lactic fermentation | Astaxanthin, hydrolyzed protein and chitin |

| Sequential treatment of crustacean shells | Chitin, proteins, lipids, carotenoids and CaCO3. |

| Demineralization and enzymatic degradation of N-acetylglucosamine | Chitin monomers |

| Sequential enzymatic, acid-alkaline extraction of shrimp cephalothorax | Chitin, chitosan, protein and astaxanthin |

| Integrated autolysis of shrimp head | Chitin, protein hydrolyzate, sulfated glycosaminoglycans |

| Sequential treatment of marine cartilage | Chondroitin sulfate, fish meal |

| Oil extraction, ethanol transesterification, n-3 PUFA concentration | Fish proteins, Glycerol, Lquid bio-fuel |

| Hydrolysis of fish waste by proteolytic enzymes | Food, Feed, Fertilizer ingredients |

| Coupled alcalase-mediated hydrolysis and bacterial fermentation | Gelatin, oils, FPH, bioactive peptides, and fish peptones |

Table 4: A few examples of seafood waste bio-refinery for multiple products having various uses.

The major problems facing the seafood industry are huge losses of nutrients through the by-catch, process waste biomass and effluents, and the environmental hazards caused by these wastes and effluents including those from aquaculture them. The current situation of stagnating oceanic resources and its adverse impacts on food security demands sustainable and cost effective secondary processing of both seafood waste biomass and process effluents. Green processes, can economically recover valuable resources and bio-energy from the waste biomass, without adverse impacts on the environment. Bio-refinery and algal technology are approaches that can have commercial potentials. The advantages of these processes include total utilization of the fishery harvest not only as food but also as sources of diverse industrial compounds, conservation of water and mitigation of seafood-related environmental hazards. Proper management of seafood discards can ultimately lead to achieve the goals of water-energy-food nexus and seafood sustainability towards bio-economy. Future developments in marine biotechnology can further help realize these goals.

Citation: Venugopal V (2021) Green Processes for Seafood Waste Management towards Bio-Economy. Poult Fish Wildl Sci. 9:231.

Received: 06-Oct-2021 Accepted: 20-Oct-2021 Published: 27-Oct-2021

Copyright: © 2021 Venugopal V. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.