Journal of Tourism & Hospitality

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0269

ISSN: 2167-0269

Research Article - (2022)Volume 11, Issue 3

For conservation project to be successful community participation plays a pivotal role. In this study, it is reflected in the community effort to conserve the Amur falcon in Pangti, Nagaland, India. However, the costs of conservation can also be quite high especially for economically marginalized rural communities. Prior to the conservation drive the high seasonal availability of the migratory bird had made its hunting a source of yearly income for the villagers of Pangti who had lost their fertile lands to submersion caused by the building of the Doyang dam. However, the mass hunting of the bird soon attracted adverse publicity resulting in a global outcry and the launch of a conservation movement which proved to be a success in fact, Pangti came to be popularly tagged by the media as one where ‘hunters-turned-conservationists’ lived. However, a section of the villagers also lost a good source of income as they had substituted bird hunting for farming, and were now bereft of livelihood, having already withdrawn from farming after the building of the dam. The promise of earning from eco-tourism was also belied. Today, those villagers struggle for their livelihoods, rendering the success of the conservation project lopsided.

Conservation; Livelihoods; Amur falcon; Migration

The Amur falcon covers one of the longest migration routes among all birds with an annual round trip of 22,000 km, which is likely to be the longest oceanic migration for any bird of prey with over 4,000 km of the outbound journey from India to Africa. They travel from eastern Asia (Russia and China) all the way to southern Africa and back every year [1]. They are considered to be one of the mightiest avian travelers in the world. These raptors leave the breeding area in Asia (Siberia) from late august to september and halt in parts of Northeast India and Bangladesh for several weeks to rest and fatten up feeding on migrating dragonflies and other insects before resuming their journey. They cross 14 countries two continents and one ocean. They arrive in their Southern African winter range by november–december. From Nagaland, it takes two months to reach their destination in Africa, including three and a half days of non-stop flight across the Arabian Sea.

These falcons are easy prey for hunters because they travel in flocks and are easy to trap using even basic traditional methods. They roost in three villages in the Wokha district of Nagaland, Pangti, Sungro and Ashaa, where they stay for around two weeks. Initially, the birds came in small numbers and the villagers thought they were carriers of diseases so they did not hunt them. However, post 2002;they started arriving in the millions. The reason for that was not really known but the conjecture was that the construction of the Doyang Dam attracted a lot of insects and therefore birds which fed on them. Thereafter, people trapped them with nets and managed to capture them in large numbers every year during the migration season. In a single day a solo hunter could trap about 400 birds and trade them for ≠20,000 to ≠80,000. These birds were considered as manna from heaven because they became a source of free food and income in a situation where the villagers had lost their most fertile and easily irrigated lands to submersion caused by the building of the dam. As a result, they had been forced to cultivate on higher grounds where elephants and other wild animals dwelled giving rise to an immediate human animal conflict. To be able to hunt the birds for food and trade was therefore a remarkable blessing in this context. As these migratory birds were available in large numbers, the villagers were able to live off them and many had even substituted farming with hunting especially since farming was steeped in uncertainty, compounded by insecure seasonal changes and human wildlife conflict.

This easy source of income did not last too long because the fact about the mass massacre of birds found its way into newsrooms (such as the British Broadcasting Corporation) documentaries and in the social media through NGOs thus causing a global outcry [2]. The church which has considerable influence on the naga social life, also conducted special service on Sundays to spread the conservation message. Eco clubs were formed and surveys on migrating birds were conducted. India is a signatory to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), and is bound by it to further the cause of conservation. It is responsible for providing a safe passage to the bird and also drawing up appropriate action plans for its long-term conservation [2]. The Amur falcon was protected under the Indian wildlife protection act, 1972 [3]. The conservationists and other protection rights activists ensured that such a massacre never happened again. Community conservation is not new to the state; there are other sites such as Khonoma, a conservation reserve. However, the Amur falcon conservation is a case of near extinction to survival owing its success to community efforts.

The conservation of the bird was a great success. For a successful conservation programme, community participation is a prerequisite. But the costs of conservation can be quite high and unsurmountable especially for rural communities that are already economically marginalized. While it is not always so, policies in favour of conservation may sometimes make a community worse off than before costing them time, resources, assets and livelihood opportunities. The main aim of this study is to bring out the impact of the Amur falcon conservation programme on the livelihoods of the local people.

Hunting conservation and livelihoods

Hunting is an important component in many household economies both as a primary source of protein employment opportunities and income [4-7].The majority of the hunters choose to hunt because there is no other source of income for them. With people’s dependence on wildlife and its meat for various reasons it is pertinent to question whether hunting can be continued indefinitely with some strategies without extirpating the species or whether hunting needs to be banned completely. argue that to protect wildlife is to stop hunting, while other scholars are not in favour of putting a stop to hunting, arguing that prohibition of hunting will be expensive and institutionally difficult [8-10]. There are also those who argue that reducing rural poverty and improving levels of income healthcare and education can prevent the destructive patterns of resource use [11].

Bird hunting once considered the primary source of subsistence has now become a source of income luxury food and a seasonal delicacy [12]. Given that hunting is an important source of livelihood in many rural areas bird hunting and its impact on livelihood cannot be considered as trivial. This raises the need to assess the socioeconomic dimensions of bird hunting, which can help in understanding the relationship between hunters and birds as one between resource users and a natural resource [13]. This in turn can help better perceive the dependence on natural resources and also make it possible to assess hunters coping ability when there are policy changes. Consequently, this can help policy makers to plan and implement policies and strategies considering the potential impacts of conservation [14].

The study in West and Central Africa addressed the issue of alternative livelihood provision and its impact on hunting [15]. They suggested that using pre-existing activities which do not require new skills was more likely to be successful. The alternative livelihood activities most frequently pursued were beekeeping, cane rat farming, livestock rearing and fish farming showed that the Tree Gudifecha project in Ethiopia improved the household’s average income from diversified livelihood activities [16]. These additional livelihoods should be substitution and not additional [17]. They must align with the needs of the people and fulfill the same characteristics of the original activity, Logically, conservation of resources should lead to development and increased opportunities of diversified livelihood, which also means that conservation success, should lead to livelihood improvement of those who are resource dependent [18].

Nature conservation is likely to promote ecotourism which, in turn, provides a means through which local people can gain economic benefits and improve their livelihoods [19]. However, only a few locals find jobs that are tourism-related because of the lack of capital, skills and education, and the high salaried jobs are usually cornered by elite immigrants or outsiders [20,21]. Some authors have argued that community conservation approaches are essential if the benefits or incentives provided in the programmers can adequately cater to local needs and offer sustainable alternative sources of livelihood [22-24]. However argues that such models do not completely understand the economic rationale and in the long run, they neither contribute to wildlife conservation nor lead to community welfare improvement [25].

Analyzed the impact of a Community Conservation Programme (CCP) implemented in a national park in Uganda over a period of seven years [26]. They concluded that communities which benefitted from the programme had a more positive attitude towards conservation than communities that did not. This is because these programmes enforce conservation policies and management on the rural poor, costing them economic opportunities, with farms and livestock lost to wildlife and resource exclusion [27-29]. Found that young age, education, shorter residency at the place were associated with positive conservation attitudes in the context of Puerto Rico. Communities that receive benefits to cover the costs of conservation are more likely to respond positively to conservation programmes. Argued that unequal benefit distribution might make it difficult to attain conservation goals because of the ‘tragedy of the commons’ [30]. They also argued that the present incentivebased conservation approaches lack consideration for issues on equal distribution of benefits [31]. To generate uniform community support one must include the marginalized communities and their traditional knowledge in planning, management and decision making [32,33].

Although there is progress in terms of inclusion of local people in management and planning, there is a lack of active participation and partnerships involving end users [34-36] argues that consequently, these disadvantaged groups may dismiss imposed restrictions because of limited returns from these programmes, leading to failure in achieving conservation plans and goals. In the context of a Mexican wetland, presented evidence on how lack of community participation in policy design could be responsible for policy failures, especially in the case of environmental policies [37].

The current management of conservation in developing countries suggests the essentiality of active community participation along with provision of benefits to them in order to reduce conflict. Thus, benefit dispersion needs to be addressed to generate maximum revenue at the local level. Understanding the local socio- environmental context to render regulations effective and enforceable can also avoid conflicts between the local communities and the policy makers [38]. In Botswana, the removal of community rights over wildlife and the ban on hunting increased human wildlife conflicts [39]. It was seen as a deprivation of their daily livelihoods [40]. Therefore, a framework that adequately compensates costs borne by the people living near the wildlife regions can go a long way towards ensuring conservation policy successes.

While the above study highlights the prevalence of studies that have discussed conservation programmes, their success and their effect on the livelihoods of local people, there is still a dearth of research on post-impact assessment of a conservation programme, especially in the context of Northeast India also acknowledged the less availability of literature on the role of local perceptions and institutions in determining socioeconomic and conservation outcomes [41]. This study tries to bridge that gap.

We undertook a research in Pangti village in the Wokha district of Nagaland in October 2018 and tried to compare livelihoods before and after conservation on the basis of livelihood assets. The village was selected because it was the highest roosting area and was the most impacted by conservation. It recorded the highest number of bird killings and was also the highest in revenue generation on account of this hunting.

The study is based on primary data collected from focus group discussions and household survey, which was carried out with interview schedule covering 84 households based on disproportionate stratified random sampling. The sample households are divided equally into 42 landowners and 42 nonlandowners. Two members of the village council, three members of the Amur Falcon Roosting Area Union (AFRAU) and an educator from the local eco club were also interviewed. The study was conducted during October to December, 2018. A translator and a local guide helped in communicating for the interviews conducted.

Conservation and the struggle for livelihood

Nagaland known for its system of property rights wherein the resources are largely community-owned and for community participation also saw the community ownership of falcon conservation which went up significantly in the local population [42]. However, not everyone was up for conservation. Although many volunteered to participate after being made aware of the conservation benefits, some felt compelled to follow the decision of the village and were sceptical of its impact on their livelihoods.

In the early stages of conservation, there was a lot of resistance and some hunters were apprehended. There were fines and other penalties imposed for hunting the bird. Eventually, with the efforts of the community and external support, conservation was made possible. The community led Amur Falcon Roosting Areas Union (AFRAU) was formed in 2014. This union, consisting of about 400 members, is comprised of landowners of the roosting sites of the falcons. The members erected check posts and carried out patrolling, resulting in zero killing of the bird.

Along with the village ban on the killing of the birds, funds were raised, a robust conservation strategy was put in place and actions were undertaken to ensure that the conservation of the falcons was successful. Various organizations and bodies such as the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), the Nagaland Wildlife and Biodiversity Conservation Trust (NWBCT), the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), the birdlife international, the natural nagas, among others got involved in the conservation drive.

Awareness was thus created in the region and it was even received well locally. The birds managed to pass through safely and continue with their migration. The local government also issued an antihunting order. Local outreach programmes were initiated and extended to the church, the students and the eco club programmes [43]. In 2013, the state of Nagaland came to be known as the ‘Falcon Capital of the World’ and went on to win awards such as the balipara foundation award and the royal bank of Scotland conservation award. The village also came to be popularly tagged by the media as one where ‘hunters-turned-conservationists’ resided. However, this success story isn’t all that there is to it.

The struggle of the villagers to search for other means of income was real and persistent because even though the Amur falcon income was only seasonal for some it was equal to an annual meager earning. With little or no incentives from the government and the NGOs, the villagers who had become dependent on the bird, now lost access to benefits derived from bird-hunting thereby having to directly bear the costs of conservation (Table 1).

| Particulars | Mean HH income (Indian rupee) | |

|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |

| Farming | 25695 (14%) | 36753 (23%) |

| Poultry | 14428 (8%) | 15400 (10%) |

| Fishery | 69185 (39%) | 58642 (38%) |

| Hunting | 42136 (24%) | 0 |

| Forest | 1425 (1%) | 2671 (2%) |

| Household industry | 2000 (1%) | 2250 (1%) |

| Interest | 15666 (9%) | 26250 (17%) |

| Total | 60268 (100%) | 25155 (100%) |

Note: Source: Primary Survey, 2018

Table 1: Sources of income.

Before conservation, the highest source of income was from fishery with a mean of ≠69185 which makes of 39% of the total sources of income followed by hunting with a mean of ≠42136 which makes 24% of the total sources of income. They earn an average annual income of ≠60268. After conservation, the highest source of income comes from fishery but has reduced to an average of ≠58642 because of increase of fishermen, unaffordable fishing equipment and lesser fish. The average annual income has reduced to ≠25155. From the data, we can conclude that there is poor financial capital that further decreased after conservation. Before conservation, fishing was the highest source of income followed by hunting but after the conservation, income from hunting reduced to zero and the mean income also dwindled greatly. Most of the villagers own lands and cultivate in their own, while some lease their lands and are paid back in tins of rice after the harvest. Many lands are family lands where they share the harvest from the same cultivating land. The percentage of households cultivating their own lands has decreased after the conservation. One reason is that people have opted to migrate to towns for better employment opportunities. The highest percentage of land holdings are the small farmers (Table 2).

| Cultivation | Before ( in percentage) | After (in percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Landless | 9.6 | 15.48 |

| Landholders | 90.4 | 84.52 |

| Marginal (0.1-2.5 acres) | 3.57 | 2.38 |

| Small (2.5- 5 acres) | 79.77 | 67.86 |

| Large (>5 acres) | 13.1 | 26.19 |

Note: Source: Primary Survey, 2018

Table 2: Land holdings.

The landowners of the roosting sites had to give up their lands for the birds to roost. On an average they gave up about 3 acres of land. The reason was that the birds did not stay to roost if there was the slightest of disturbance. At the same time, the excreta from the birds were excessive and too toxic for vegetation to grow. The roosting area was teeming with rubber, teak, banana and other plantations, and these were left untouched for the sake of the birds, resulting in some landowners having to give up their plantation land unwillingly. Nothing much was done to compensate the landowners or the hunters whose livelihood depended on the lands and the birds. The government provided poultry scheme to help them start a livelihood but the scheme covered only a few households and it was unsustainable even for those beneficiaries. The forest department funded the construction of waiting sheds, watchtowers but this did not boost the village economy.

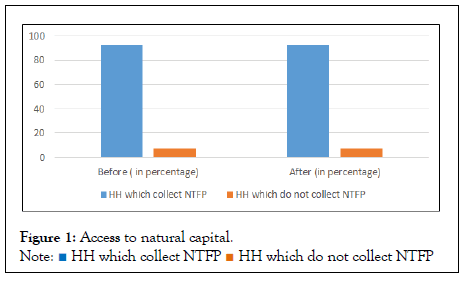

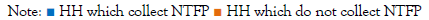

Initially, grants for village development were allotted under the supervision of the village council but it invited dissent from the landowners who preferred to be compensated directly as they had to give up their lands which otherwise had potential to be used for cultivation and plantation. The Amur Falcon Roosting Area Union (AFRAU) emerged as a result, to address the grievances and needs of the landowners. With time, grants for development were replaced with incentives for activities such as poultry farming, employment in the form of tourist guides, protection squads, boatmen, etc. For these activities, villagers were paid about ₹500 per day. However, these efforts were neither sufficient nor sustainable. The reason was that there were not enough people employed or employable, and the incentives were not distributed equally. Also, these were only seasonal employment and were inadequate in meeting the year-round needs of a household without the pursuance of other livelihood options. Only a few of the targeted beneficiaries (landowners) were able to access them. This only led to differences between the two bodies. Hence, the landowners and hunters, in order to sustain themselves and their families, had no other option but to go back to farming and fishing. For some, it meant migrating to the nearby towns for employment. This also meant development of a negative attitude towards conservation because it implied that conservation occurred at the cost of their livelihoods. To ensure sustainable conservation, the endeavor needs to be feasible from an economic point of view too. The availability of natural capital is, however, fairly good Figure 1. With the ban on hunting, the villagers had to decrease their dependence on wild animals for food and trade while the use of non-timber forest products continued to remain fairly high. Nearly 93 % of the households collect Non- Timber Forest Product (NTFP) for their own consumption like wild berries, wild green leafy vegetables some medicinal herbs and organic soils. About 7% collect them to sell. There is no change in this trend with before and after conservation. The annual average earning from NTFPs sold amount to ≠1400 before conservation. After conservation it has increased to ≠2600 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Access to natural capital.

Figure 2: Lending Household percentage.

In the initial years of conservation, there was a lot of hope for economic improvement in the village, be it from the increased attention from the tourists or from the policy makers. The media stories that covered the conservation of the Amur falcon reported that there would hopefully be many potential employment opportunities flowing from it for example, as tourist guides, boatmen, homestay owners, and other such tourism-related earning avenues. But, even after years of conservation, there hasn’t been any significant development that could possibly usher in sustainable alternative livelihoods for the villagers. Tourists come annually in thousands, which could have become a good source of revenue. There are opportunities for some households to offer their home as homestays to tourists and other visitors. However, the tragedy is that since there are no basic facilities that could be availed in the roosting sites and in the village, tourists prefer to return to nearby towns where there are better facilities. In effect, the visitors do not stay back in the village as was expected. There are camping sites near the roosting areas but they lack proper sanitation facilities. There are employment opportunities as protection squad members and guides, but sufficient revenue is not generated from them to cover the expenses of a household.

Families which were dependent on the birds were the most affected ones. They were earning about ≠20,000 to ≠80,000 annually per season, an income equivalent to their annual return from other sources. Having no other proper means of alternative sources of income, they had to shift their children to government schools, which are usually known for lower quality of education. Many had to borrow money to maintain their earlier standard of living that came with the hunting of birds. To pay for fees or food, some had to sell their livestock, mainly poultry and pigs which were initially reared for their own consumption. Even though income from hunting was seasonal, it was equivalent to their annual earnings, so the ban on hunting caused their income to plummet sharply. Business was affected too as the sales in the small shops were better before conservation (Figure 2).

To pay for fees or food, some had to sell their livestock, mainly poultry and pigs which were initially reared for their own consumption. Even though income from hunting was seasonal, it was equivalent to their annual earnings, so the ban on hunting caused their income to plummet sharply. Business was affected too as the sales in the small shops were better before conservation.

There are two primary health centers in the village. However, there is often a lack of medical supplies because of poor access to pharmacies and hospitals, which, in turn, is due to poor road conditions that are pervasive. With the conservation wave, the basic facilities seemed to have improved a little because of the attention from the government. Visitations to the health centers have also increased, but access to supplies from outlets is still difficult because of the unchanging poor road conditions. Around the season of the birds’ migration, the AFRAU repairs roads, collecting funds from among themselves and setting up posters to welcome the tourists, all without any aid from the government. There is a government middle school in the village that offers education till class 8th. For higher education, the villagers have to go to other villages.

On being asked whether he supports conservation policies or not, a respondent replied that he would go back to hunting without hesitation if he were not part of the AFRAU. But as a landowner and as a part of the conservation union, he admitted that he had no other option but to agree to participate in conservation efforts like the others. This response did not seem to be too surprising or uncommon, since many of the respondents felt the same way. Though the conservation was a community effort, many of the participants complied with the rules and regulations of the village, owing to their responsibility towards the landowners’ union or the village and not really due to their desire to engage in conservation activities. However, some educated people were keen on conserving the bird, knowing the benefits of conservation and the adverse effect of a missed factor on the food chain and other such ecological consequences. But there were very few people like them. It was also observed from the survey that many of the villagers, particularly the landowners and the hunters, were frustrated at how the conservation project impacted their livelihoods, with most of them preferring their livelihoods to conservation.

A closer look at the community after the conservation effort reveals a struggle for livelihoods. The loophole that conservation policies had was that they did not offer an effective sustainable alternative source of livelihood to the villagers who had become dependent on the bird. Not everyone was dependent on the birds for their income but there were definitely a lot of them who had turned to hunting and had given up farming and fishing. There were landowners who had to give up their lands, hunters who had to give up hunting and had to look for other sources of income. After the ban, there were hardly any villagers who could make ends meet because the income from bird-hunting used to be such that it had covered the expenses of the children’s school fees and supported the family throughout the year. One of the families lamented that after the ban on hunting the bird, four of their children had to discontinue studies because there wasn’t enough money to support their education. And that is just one family among many others facing a similar predicament.

The study concludes that there is no positive impact of conservation on the livelihood of the villagers on the basis of comparisons of livelihood assets made as part of the research. This is because there is no secure access to or ownership of such assets. No sustainable alternative livelihood option has been introduced after the birdhunting source of income got discontinued. The few incentives that were provided for practicing conservation were unequally distributed, which resulted in differences and conflict. What could have been a thriving tourist hotspot and could have made ecotourism a source of livelihood did not or hasn’t yet lived up to its potential. A community that is dependent on natural resources for its livelihood is seldom ready to give up its primary source of livelihood for a conservation cause without the availability of sustainable alternatives. Conservation by itself is necessary and vital not only for the survival of a species but also for the effect it has on the food chain and due to other environmental consequences. But, along with it, come tradeoffs, need for alternative livelihoods, sustainable approaches and so on. If these factors are not carefully considered, conservation projects may turn out to be more detrimental than beneficial. Conservation cannot be considered sustainable unless it assures biological and socio-economic stability and security. In the case of the Amur falcon conservation even though there was complete success in conserving the bird the same cannot be said about the economy of the village, as the conservation project had an undesirable impact on the village of Pangti.

Numerous pleas have been made and media attention has been sought to help in the provision of basic facilities and other incentives for the affected villagers. But, so far, nothing has been done except tagging a prestigious label on the village and applauding the villagers as ‘hunters-turned-conservationists’. If this persists it will be no surprise if these ‘hunters-turned-conservationists’ return to their old means of livelihood, even if it means exterminating the whole species of Amur falcon to secure the survival needs of their families.

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

[Cross ref] [Google scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Mero NU, Mishra PP (2022) Hunting Vs. Conservation of the Amur Falcon: Livelihood Struggles in Nagaland, India. J Tourism Hospit. 11: 496.

Received: 06-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JTH-22-17788; Editor assigned: 08-Jun-2022, Pre QC No. JTH-22-17788(PQ); Reviewed: 22-Jun-2022, QC No. JTH-22-17788; Revised: 29-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JTH-22-17788; Published: 06-Jul-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0269.22.11.496

Copyright: © 2022 Mero NU, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.