Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2593-9173

ISSN: 2593-9173

Research Article - (2022)Volume 13, Issue 5

The research assessed youth involvement in plantain value chain in Ondo State, Nigeria. It examined the characteristics of the respondents, determined their level of involvement and constraints to their involvement. A multi stage sampling procedure was used to select 120 respondents for the study. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data collected. Detailed results show that higher percentage (59.2%) of female were involved in the plantain value chain with average annual income of 98666.67 ± 18422.37 and all (100%) the respondents had formal education. Their mean age was 33 ± 4 years. There was a significant relationship between their annual income (r=0.211, p ≤ 0.05), years of experience (r=0.245, p ≤ 0.01) and involvement in plantain value chain activities. The study concluded that many of the respondents were moderately involved in plantain value chain activities; its can promote national food security and reduce unemployment problem. The study recommended among others that training in plantain value chain activities should be organized by development stakeholders to promote youth involvement in plantain value chain activities.

Assessment; Youth; Involvement; Plantain; Value chain

Nigeria operates basically an agricultural economy with over 70 % of the population actively engaged in farming at various levels [1,2]. Agriculture is the subsector of national economy which contributes immensely to the development of the economy through foreign exchange. It is the main source of raw materials for industries, provision of food for increasing population, provision of employment and creation of market for industrial products. Nigeria agriculture features tree crops, forestry, livestock and fisheries. Agriculture is one of the sectors that have a critical role to play in poverty reduction in Nigeria as over 40 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) comes from the sector and it employs about 60 percent of the working population [3,4].

According to the challenge facing Nigeria today is that of feeding her teeming population and youth unemployment as a socio-economic problem challenging the sub-Saharan Africa. The way forward is to encourage youth to engage in agricultural production focusing on food crops that could help mitigate food insecurity and poverty in Nigeria. Much concentration is placed on high quality grains, tubers and livestock or poultry products. However, there are other high nutritive and medicinal food items which are of economic value that are often neglected by the youth. Plantain is one of such food crops that could fulfil those requirements [5,6].

Plantain is one of the most important horticultural crops and it is among the ten most important food security crops that feed the world and has always been an important staple food for both rural and urban populace [7,8].Plantain belongs to the non-traditional sector of the rural economy, where it is used mainly to shade cocoa and contain essential components of human and livestock’s diet [9]. Its fruit are edible, and are generally used for cooking. Plantain are important food crops in Sub-Sahara Africa, providing more than 25 percent carbohydrate and 10 percent calorie intake for approximately 70 million people in the region [10,11].

Plantain is of great socio-economic importance in Nigeria from the view point of food security and job creation. In addition to being a mainstay for rural and urban consumers, plantain provides an important source of revenue for smallholders, who mainly produce them in compound or home gardens (International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, IITA, 2016). The economic importance of plantain lies in its contribution to subsistence economy [12]. The continuous availability of harvested bunches from established areas makes it possible for the crop to contribute to all year round food security for consumers also income for producers processors and marketers. Plantain has the potential to contribute to strengthening national food security and decreasing rural poverty [7]. This could be achieved through youth involvement in the different activities of plantain value chain such as production, processing and marketing of plantain. Agricultural value chain is considered as an economic unit of analysis of a particular commodity or group of related commodities that encompasses a meaningful grouping of economic activities that are linked vertically by market relationships.

Youth could be defined as phase of individual development between childhood and adult. Commonwealth secretariat defines youth as people in the category of 13-30 years. The United Nations definition of youth argued that youth start with a lower age of 15 years and upper age limit as 39 years of age [13]. Youth aged 10-24 years, are 27 percent of the world’s population and 33 percent of the population in Africa [14]. Worldwide, it is estimated that there were 1,200 million youths in year 2000, 53 percent of who live in rural areas [1]. According to Food and Agricultural Organisation of United States (FAO) (2014), global population is expected to increase to 9 billion by 2050, with youth (15-24) accounting for about 14 percent of this total. Sustainable agricultural production in Nigeria could only be achieved through the mobilization of the large numbers of youth as active participants since youth dominate in Nigeria. United Nations’ definition of youth was adopted in this study.

Agriculture constitutes the main occupation of the people in Ondo state. The state is one of the major producers of plantain producing state in Nigeria. Other agricultural products include cocoa, yams, cassava and palm. Government in Ondo state has, therefore, put in place the new generation farmers programme as means of empowering the youth and increasing the population of farmers so that agricultural productivity can hike and alleviate poverty in the state. The agriculture sector employs about two-thirds of the total labour force and prove livelihood for about 90 percent of the population. Most studies on Plantain in Nigeria have been on Production for example, Baruwa et al, (2011) [15], Agronomy [16], Marketing [12], Processing and Post-Harvest losses [17,18]. Furthermore, statistics on rural youth that are involved in plantain are lacking. Youth constitute the most important sector in a society and they are one of the greatest assets that any country could have and as such must not be neglected.

Ondo state is one of the Nigeria states that have best comparative advantage for plantain farming because of the vibrant and favourable climate. Considering the nutritional and medicinal importance of plantain, venturing into its enterprise holds a promising potential [12]. However, research shows that the age bracket with the highest population distribution is the (41-50.99) years which constitute 38.6 percent of the farmers that are engaged in plantain production in Nigeria. This result suggests that the farmers are ageing which could result in the reduction of the available energy and in the efficiency of farmers supervising their farming operations [10].

One of the setbacks of Nigerian agricultural production is attributed to the low level of involvement of youth and the inability of the Federal Government to integrate youths into the mainstream of the numerous agricultural development programmes implemented over the years [19]. The situation described above arouses the need to assess the level of youth involvement in plantain production, processing and marketing in Ondo state. This study assessed the level of youth involvement in plantain production, processing and marketing as a source of employment and enhancing food security in Ondo state with aim of determining the socio-economic characteristics of rural youth that are involved in plantain production, marketing and processing in the study area; identified the level of their involvement; examine their perception towards their involvement and examined constrains militating against youth involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing. The study tested the following hypotheses in null forms: there is no significant relationship between the socio-economic characteristics of the rural youth and their involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing; also, there is no significant relationship between the rural youth perception and their involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing.

The study was conducted in the rural area of Ondo State, Nigeria. Ondo state was created from the defunct Western Region on 3rd February, 1976 with capital in Akure. The coordinate of the state is 7° 10′N 4°840′E and it covers a land area of 14,793 square kilometres. According to analytical report of the National Population Commission (2006), Ondo state has 3,441,024 people with eighteen local government areas. Ondo state is located in the south-western geopolitical zone of Nigeria and bounded in the North by Ekiti and Kogi states, in the East by Edo state, in the west by Osun states in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. The state’s Economy is basically agrarian with large scale production of cocoa, palm produce and rubber. Other crops like maize, kolanut, yam and cassava are produced in large quantities. The population of the study was youth between the ages of 19years to 40 years as defined by Adedoyin (2005) in the children-in-Agriculture Programme in Nigeria. Youth involved in plantain production, marketing and processing within this age range in the selected communities were selected for the study. A multi-stage sampling procedure was used for sample selection. In the first stage, one LGA was purposely selected from each of the four Agricultural zones in Ondo state based on predominance of plantain production in the area. These LGAs were: Akoko North West from Owo/Akoko Zone, Ile-oluji/Oke-Igbo from Ondo/Odigbo Zone, Okitipupa from Okitipupa/Irele Zone, and Akure South from Akure/ Ifedore/Idanre Zone. Secondly, three rural communities were randomly selected from each LGA namely: Ikaram, Ase and Irun from Akoko North west; Aule, Irese and Olokuta from Akure south; Modebiayo, Ilado and Lepa from okitipupa. In all, twelve rural communities were selected. Lastly simple random sampling technique was used to select ten respondents from each of the community for the study because the researchers do not have the list of youth in each community. In all, 120 respondents were selected for the study. Data were collected by using interview schedule at individual level in the study area. The questions were drawn in English language in the major areas based on the objectives of the study. Involvement of youth in plantain production, marketing and processing was measured using a 4-point rating scale which ranges from: Not Involved (NI)=0, Rarely Involved (RI)=1, Moderately Involved=2 and Highly Involved=3. The total involvement score per respondent was further classified into three levels: high, medium and low using mean score plus/minus standard deviation. That is high for scores above mean plus standard deviation; low for scores below mean minus standard deviation; and medium for scores between the two. The respondents’ perception was measured by asking the respondents to react to eight perceptional statements. Their reaction were against five-point Likert-type scale of strongly agree (5), agree (4), undecided (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1) for the positive and vice versa for the negative statements. The total perception score per respondent was further classified into three categories: positive, indifferent and negative using mean score plus/minus standard deviation. That is: positive for scores above mean plus standard deviation; negative for scores below mean minus standard deviation; and indifferent for scores between the two. Descriptive statistics such as mean, frequency count, percentages, means and standard deviations, together with inferential statistics such as Pearson Product Moment Correlation were used to analyze the data collected.

Socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

The results in Table 1 reveal that higher percentage (59.2%) and of the respondents were female, this might be as a result of plantain value chain activities are not too strenuous for female gender; many (65.0%) and (50.8%) were married and Christians respectively with average household of 3.39 ± 2.14, their mean age was 33.62 ± 4.54 with mean of annual income from plantain value chain activities of N 98666.67 ± N 18422.37. This implies that the respondents were in their active and productive age which could be deployed effectively to plantain value chain activities; Furthermore, analyses shows that majority (89.2%) indicated farming as their parents’ main occupations which positively influence their involvement in plantain value chain activities, their mean years of education was 11.60 ± 2.60. Many (65%) indicated that their main occupation was farming. The findings agreed with Adeniji, et al., (2010) claims that rural dwellers either directly or indirectly depend on agriculture.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | Central tendency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | - | - | - |

| 22-26 | 12 | 10 | 33.62 ± 4.54 |

| 27-30 | 18 | 15 | |

| 31-35 | 40 | 33.3 | |

| 36-40 | 50 | 41.7 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 49 | 40.8 | |

| Female | 71 | 59.2 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 33 | 27.5 | |

| Married | 76 | 65.5 | |

| Divorce | 9 | 7.5 | |

| Religion | - | - | - |

| Christianity | 61 | 50.8 | |

| Islam | 59 | 49.2 | |

| Household size | |||

| 03-Jan | 48 | 40 | 3.39± 2.14 |

| 06-Apr | 72 | 60 | |

| Annual income (₦) earned from plantain value chain activities | |||

| 80, 000- 100, 000 | 88 | ||

| 101, 000 - 120, 000 | 21 | 98666.67±18422.37 | |

| 121, 000 - 140, 000 | 8 | ||

| 141, 000 - 150, 000 | 3 | ||

| Years of formal Education | |||

| Below 6 | 18 | 15 | 11.60 ± 2.60 |

| 12-Jul | 80 | 66.7 | |

| 13-16 | 22 | 18.4 | |

| Years of experience in plantain value chain activities | |||

| 07-May | 28 | 23.3 | 9.22± 2.28 |

| 10-Aug | 57 | 47.5 | |

| 15-Nov | 35 | 29.2 | |

| Parents’ Occupation | |||

| Farming | 107 | 89.2 | |

| Trading | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Teaching | 4 | 3.3 | |

| Main occupation | |||

| Farming | 78 | 65 | |

| Fashion designing | |||

| Trading | 31 | 25.8 | |

| Teaching | 4 | 7.5 | |

Note: Source: Field survey, 2017.

Table 1: Distribution of respondents by their socio economic characteristics n= 120.

Involvement of rural youth in plantain production, marketing and processing

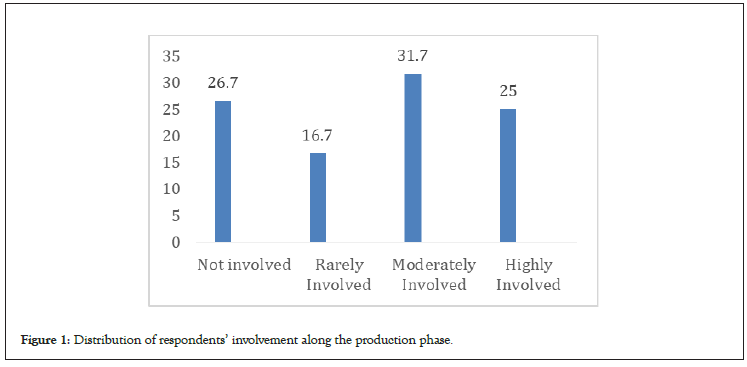

Production phase

Results in Figure 1 show among other that 31.7 percent of the respondents were moderately involved and 25.0 percent of the respondents were highly involved in plantain production. The low involvement in production phase of plantain might be as a result of its strenuous nature. This result is also in agreement with that of Faturoti et al, (2007) [20] and Akinyemi et al, (2010) [21] that recorded low plantain production and farmers growing the crops either for home consumption or for local markets. The activities in production phase include establishment and management of the farm such as land clearing, planting, weeding, application of fertilizer and harvesting and most cultivated specie of plantain in the study area is “hybrid agbagba” the giant elephant plantain specie.

Figure 1: Distribution of respondents’ involvement along the production phase.

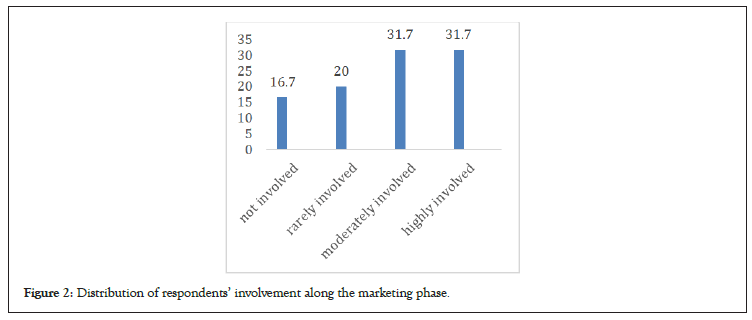

Marketing phase

Result in Figure 2 show among others that 31.7 percent were moderately involved and 31.7 percent were highly involved in marketing of plantain. Activities relating to marketing phase include on-farm/off-farm selling of harvested matured plantain fruits to wholesalers, retailers and consumers. On the other hand, some marketers which Adeoye et al., 2013 identified as the assemblers move around farms, collect the produce from farmers at low prices and transport it to the cities where they hand them over to wholesalers, who in turn pass it on to retailers vendors for sale to consumers. Women of all ages, including youth, dominate plantain marketing either as assemblers, wholesalers or retailers in the study area. Retailers source their bananas locally especially from farmers, wholesalers, fellow retailers and their own farms. This study also agrees with Adesope et al, (2004) [22] and Adeoye et al, (2013) [7] who identified many intermediaries in the marketing of plantain in Nigeria.

Figure 2: Distribution of respondents’ involvement along the marketing phase.

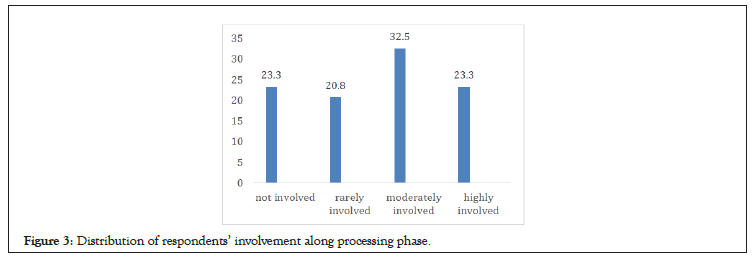

Processing phase

The results in Figure 3 among others show that 32.5 percent were moderately involved and 23.3 percent were highly involved in plantain processing. The processor buys directly from Assemblers and from the producers and they mostly operate on a small scale using rudimentary implements in the processing business. This result is in tandem with that of Ekunwe and Ajayi, (2000) [23] and Tchango et al., (1999) [24] who identified Plantain chips and plantain flour respectively as the most popular plantain products in Nigeria. Plantains in the study area are processed into different types of products such as plantain chips, and plantain flours. Plantain chips are created by frying slices of unripe or slightly ripe plantain pulp in vegetable oil, and are packaged in plastic or aluminum sachets. Plantains are also made into flour by peeling the plantains, cutting the pulp into pieces and air drying it, and then grinding the dried pulp in a wooden mortar or corn grinder. Processing fresh plantain helps to increase the shelf life of plantain and thus helps plantain to be stored longer than in its fresh state.

Figure 3: Distribution of respondents’ involvement along processing phase.

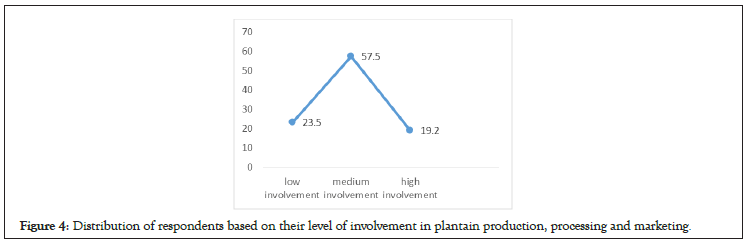

Overall level of involvement

The results in Figure 4 reveal that 57.5 percent (3.0> level of involvement <3.5) of the respondents has medium level of involvement among others. These findings is in line with that of Chikezie et al, (2012) [4] and Ayanlaja et al, (2010) [6] that reported fair involvement of rural youth in cassava value chain activities in Imo State, Nigeria.

Figure 4: Distribution of respondents based on their level of involvement in plantain production, processing and marketing.

Perception of youths towards plantain value chain

The results in Table 2 reveal among others that, about 30.8 and 25 percent of the respondents strongly agree that involvement and enlightenment of rural youths can lead to the improvement in the socio-economic conditions of rural youths and motivate their involvement in plantain value chain activities. Also, 23.3 percent strongly agree that the availability of alternative income generating activities either in other crops or non- farming activities does affect rural youth involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing. While about 21.7 percent strongly agree that these activities can earn high profit like other crops in agriculture. This indicates that rural youth believed that these plantain activities are profitable and can earn enough income that can sustain them.

| Variables | SAF (%) | AF (%) | UF (%) | DF (%) | SDF (%) | Mean + SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plantain production, marketing and processing can fulfil rural youths socio-economic needs |

26 (21.7) | 30 (25.0) | 12 (10.0) | 32 (26.7) | 20 (16.7) |

2.08 + 1.433 |

| Plantain production, marketing and processing is a source of employments for rural youths |

24 (20.0) | 37 (30.8) | 6 (5.0) | 31 (25.8) | 22 (18.3) | 2.17 + 1.497 |

| Government support and incentives are good motivator for youth involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing |

27 (22.5) | 37 (30.8) | 5 (4.2) | 27 (22.5) | 24 (20.0) | 2.16 + 1.484 |

| Enlightenment can motivate youth involvement in production, marketing, processing of plantain |

30 (25.0) | 51 (42.5) | 16 (13.3) | 15 (12.5) | 8 (6.7) | 2.05 + 1.214 |

| Plantain production, marketing and processing can provide incentives for rural youths |

27 (22.5) | 28 (31.7) | 5 (4.2) | 27 (22.5) | 23 (19.2) | 2.25 + 1.324 |

| Plantain production, marketing and processing can earn income like other activities in agriculture |

26 (21.7) | 41 (34.2) | 20 (16.7) | 17 (14.2) | 16 (13.3) | 2.37 + 1.328 |

| Availability of alternative income generating activities has no effects in youth involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing |

28 (23.3) | 27 (22.5) | 20 (16.7) | 23 (19.2) | 22 (18.3) | 2.15 + 1.442 |

| Youth involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing can lead to the improvement of rural youth socio-economic conditions |

37 (30.8) | 39 (32.5) | 10 (8.3) | 24 (20) | 10 (8.3) | 2.62 + 1.367 |

Table 2: Distribution of respondents based on their perception towards plantain production, marketing and processing.

Constrains militating against youth involvement in plantain value chain activities

Production phase constraints

The results in Table 3 reveal that main constraints with their mean value were poor road condition (2.38), pilferage (2.08), inadequate storage facilities (2.21) and marketing (2.4) among others. The main constraints as indicated by the respondents were poor road condition and credit inaccessibility. This finding also agree with Olokundun et al, (2012) and Ebiowei (2013) [25] who reported that the major problems in plantain production were inadequate capital, poor transportation, frequent and long period of drought, marketing challenges and lack of storage facilities.

| Variables | Not severe F (%) | Severe F (%) | Fairy severeF (%) | Highly severe F (%) | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High transport cost | 10 (8.3) | 14 (11.7) | 17 (14.2) | 79 (65.8) | 2.38 | 1st |

| Pilferage | 9 (7.5) | 12 (10) | 59 (49.2) | 40 (33.3) | 2.08 | 3rd |

| Inadequate storage | 4 (3.3) | 20 (16.7) | 47 (39.2) | 49 (40.8) | 2.21 | 2nd |

| Land inaccessibility | 14 (11.7) | 37 (30.8) | 49 (40.2) | 20 (16.7) | 1.68 | 6th |

| Inadequate manpower | 27 (22.5) | 23 (19.2) | 44 (36.7) | 26 (21.7) | 1.58 | 7th |

| Credit inaccessibility | 9(7.5) | 22(18.3) | 51(42.5) | 38 (31.7) | 1.98 | 5th |

| Inadequate training | 25 (20.8) | 47 (39.2) | 32 (26.7) | 25 (20.8) | 1.33 | 8th |

| Marketing problems | 11 (9.2) | 22 (18.3) | 38 (31.7) | 49 (40.8) | 2.04 | 4th |

Note: Source: Field survey, 2017. Frequency (F).

Table 3: Distribution of respondents based on constrains militating against youth involvement in the production phase.

Marketing phase constraints

The results in Table 4 reveal that main constraints with their mean were high transportation cost (2.10), inadequate storage facilities (1.82) and pilferage (2.00) among others. Major constraints in marketing phase of plantain were high cost of transportation, credit inaccessibility and inadequate storage facilities. This result is in agreement with that of Miller and Jones (2010) [26] and Noorman, (2013) who reported that lack of good infrastructures and facilities for storage as well as processing coupled with the means of transport needed serious improvement in plantain marketing system.

| Variable | Not severe F (%) | Severe F (%) | Fairly severe F (%) | Highly Severe F (%) | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High transport cost | 17 (14.2) | 10 (8.3) | 37 (30.8) | 56 (46.7) | 2.1 | 1st |

| Pilferage | 46 (38.3) | 15 (12.5) | 16 (13.3) | 43 (35.8) | 1.82 | 4th |

| Inadequate storage facilities | 12 (10.0) | 28 (23.3) | 50 (41.7) | 30 (25.0) | 2 | 3rd |

| Credit inaccessibility | 41 (34.2) | 29 (24.2) | 10 (8.3) | 40 (33.3) | 2.07 | 2nd |

| Inadequate manpower | 46 (38.3) | 15 (12.5) | 16 (13.3) | 43 (35.8) | 1.26 | 7th |

| Inadequate training | 51 (42.5) | 20 (16.7) | 32 (26.7) | 17 (14.2) | 1.38 | 6th |

| Marketing problems | 11 (9.2) | 22 (18.3) | 38 (31.7) | 49 (40.8) | 1.74 | 5th |

Note: Source: Field survey, 2017. Frequency (F).

Table 4: Distribution of respondents based on constrains militating against youth involvement in plantain marketing phase.

Processing constraints

The results in Table 5 reveal that main constraints with their mean were credit inaccessibility (2.08), inadequate training (2.06), adequate storage facilities (2.09) and credit inaccessibility (2.08) among others. These findings are similar to that of Ekunwe and Atalor, (2007) [23], Folayan and Bifarin, (2011) [18] and Odemero, (2013) [27] who reported that the major constraints of plantain processors include poor transportation, poor storage, inadequate capital, inadequate labour supply and technology [28-34].

| Variable | Not severe F (%) | Severe F (%) | Fairly severe F (%) | Highly Severe F (%) | Mean | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor road condition | 31 (25.8) | 30 (25.0) | 27 (22.5) | 31 (25.8) | 1.5 | 5th |

| Pilferage | 80 (66.7) | 16 (13.3) | 20 (16.7) | 4 (3.3) | 0.8 | 7th |

| Inadequate storage | 26 (21.7) | 50 (41.7) | 5 (4.2) | 39 (32.5) | 2.09 | 1st |

| Credit inaccessibility | 13 (10.3) | 15 (41.7) | 42 (35.0) | 13 (10.3) | 2.08 | 2nd |

| Land inaccessibility | 90 (75.0) | 10 (8.3) | 11 (9.2) | 9 (7.5) | 0.49 | 8th |

| Inadequate manpower | 59 (49.2) | 11 (9.2) | 34 (28.3) | 16 (13.3) | 1.09 | 6th |

| Inadequate training | 16 (13.3) | 26 (21.7) | 39 (32.5) | 39 (32.5) | 2.06 | 3rd |

Note: Source: Field survey, 2017. Frequency (F).

Table 5: Distribution of respondents based on constrains militating against youth involvement in plantain processing.

Hypotheses testing

The results in Table 6 show that there were positive and significant relationship between annual income from plantain value chain activities (r=0.211, p ≤ 0.05), years of experience in plantain value chain activities (r=0.245, p ≤ 0.01) and their involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing. In view of this result, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between selected socio-economics characteristics and their involvement in plantain value chain activities is rejected and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. This implies that an increase in annual income from plantain value chain activities and year of experience in plantain value chain activities will result to an increase in their involvement in plantain value chain activities.

| Variable | Correlation coefficient (r) | Sig (P) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 0.034 | 0.71 | NS |

| Years of experience | 0.245** | 0.007 | S |

| Household size | 0.023 | 0.565 | NS |

| Average income earned | 0.211* | 0.008 | S |

| Years of education | 0.065 | 0.485 | NS |

Note: **r is significant@0.01 level,*r is significant@0.05 level, S= significant, NS=Not significant.

Source: Field survey, 2017.

Table 6: Pearson correlation show relationship between socio-economic characteristics of the youth and their level of involvement in plantain production, marketing and processing.

Also, results in Table 7 show that there was positive and significant relationship between involvement of youth in plantain value chain activities and the perception (r=0.200, p ≤ 0.05) of respondents towards involvement in plantain value chain activities. In view of this result, the null hypothesis that there is no significant relationship between perception and their involvement in plantain value chain activities is rejected and the alternative hypothesis is accepted. This implies that the more positive their perception towards involvement in plantain value chain activities [35-37].

| Variable | Correlation coefficient (r) | Sig (P) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perception | 0.200* | 0.028 | S |

Note: Level of significant=0.05 (P < 0.05), S=Significant.

Source: Field survey, 2017.

Table 7: Pearson correlation shows the relationship between the level of involvement in plantain production, marketing, processing and their perception.

Based on the findings of the study, it was concluded that many of the rural youths were moderately involved in Plantain value chain activities in the study area. Main constraints to their involvement in plantain value chain activities were prevailing high cost of transportation, poor/inadequate storage facilities, credit inaccessibility and inadequate trainings among others. It was recommended among others that agricultural and rural development stakeholders should encourage on-farm and development trainings for youth on plantain value chain activities; and provide adequate policies and legislations for improved and easier access to resources such as capital, technology and information which would help the youth develop keen interest and be actively involved in plantain production, marketing and processing.

[Crossref]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref]

[Crossref]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref]

[Crossref]

[Crossref]

[Crossref].

[Crossref]

Citation: Ayinde J, Adeloye KA, Alao OT, Ser OB (2022) Assessment of Youth’s Involvement in Plantain Value Chain Activities in Ondo State, Nigeria. J Agri Sci -Open Access. 13.500.

Received: 05-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JBFBP-20-004-PreQC-22; Editor assigned: 07-Sep-2022, Pre QC No. JBFBP-20-004-PreQC-22 (PQ); Reviewed: 22-Sep-2022, QC No. JBFBP-20-004-PreQC-22; Revised: 29-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. JBFBP-20-004-PreQC-22 (R); Published: 06-Oct-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2593-9173.22.13.500

Copyright: © 2022 Ayinde J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.