Family Medicine & Medical Science Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2327-4972

ISSN: 2327-4972

Research Article - (2020)Volume 9, Issue 3

Background: Depression is a significant contributor to the global burden of disease. Primary care physicians are the initial health care contact for most patients with depression to provide early detection and continuous management for depressed patient. Despite this opportunity, care for depression is often suboptimal.

Objective/Aim: To assess performance of family physicians for early detection and management of depression according to the Egyptian guidelines. Subjects and Methods: a cross sectional study, conducted on 55 family physicians in training working in academic family practice centers and outpatient family medicine clinic affiliated to Suez Canal university hospital. Comprehensive sample used according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study group conducted a semistructured questionnaire modified from the Egyptian guidelines and Meredith et al. developed by the researcher and revised by a psychiatrist.

Results: Regarding the adherence of family physicians to the Egyptian guidelines for diagnosis and management of depression, (70.9%) of the family physicians were not adherent, while (74.5%) were not adherent to the Egyptian guidelines regarding the prescription of antidepressant medications. The barriers to care of depressed patients include: 82% of the participants admitted low confidence in overall management of depression, 89% mentioned patient denial to see mental health professional and 80% of them considered that inadequate time to provide counseling or health education were the main barriers to providing optimum care.

Conclusion: the present study reveals that most of the family physicians participated in the study were poorly adherent to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression. So, an intervention program including on job training to overcome addressed barriers to the best practice and knowledge gaps should be conducted.

Physicians; Depression; Egyptian guidelines; Family physicians

Depression is a significant contributor to the global burden of disease and affects people in all communities across the world; approximately 350 million people worldwide suffer from depression at any given time [1]. The average lifetime prevalence of depression is 17%- 26% for women and 12% for men in developing countries [2]. The estimated prevalence of depressive disorders is 13-22% in primary care clinics in developing countries but is only recognized in approximately 50% of cases [3]. Primary care physicians are the initial health care contact for most patients with depression and are in a unique position to provide early detection and continuous management for persons with depression. The US preventive service task force issued new depression screening recommendations encouraging primary care physicians to routinely screen their adult patients for depression. Physicians should have systems in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment and follow-up [4]. Barriers to early detection and management of patient with major depressive disorder by family physician include: Physician barriers, Patient barriers and Organizational barriers [5]. As an attempt to overcome such circumstances, ceaseless efforts have been made worldwide for the development of an evidencebased clinical practice guidelines that would suggest therapeutic recommendations systematically. Evidence based guidelines aim to encourage practices that the evidence suggests are beneficial and to discourage ineffective or potentially harmful practices [6].

The current study was a cross sectional study was conducted on 55 family physicians in training (Master Degree, Diploma and MD) working in academic family practice centers and outpatient clinic affiliated to the Family Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Egypt. The study population subjected to semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire, modified from the Egyptian guidelines and Meredith LS et al., developed by the researcher, revised by the supervisors and psychiatrist (consultant).

The questionnaire composed of three parts:

The First Part

Socio-demographic data of family physician including: code number, age, gender, qualification, years of experience, receiving training in mental health, number of depressed patient seen over the last year, the number of articles read about major depression, number of mental health consultations ,the number of times received orientation about antidepressants by a pharmaceutical company representative , number of requests for a specialty referral or for antidepressant medications and need to change or improve the way to care for depression.

The Second Part

Specific items to measure knowledge of family physicians for early detection and management of depression which are:

-General knowledge of family physicians about depression.

-Ability of family physicians to prescribe proper treatment.

-Aggregate score (all 13 items), general items (1, 4, 7 and 13), Anti- Depressants items (3, 5, 6, 9, 10 and 12), Psychotherapy items (2, 8 and 11).

-Each statement is rated on 5-point Likert scale ranging from definitely true to definitely false. Scoring was done by adding one point for each correct answer of total 13 points according to the model answer, scoring was poor if ˂60%, accepted knowledge score if ≥ 60%.

The Third Part

Barriers to early detection and management of depression explored in details including: physician barriers, patient barriers and organizational barriers.

The mean age of the participants who included in the study was 32 ± 3.915 years old with predominance of females (80%). Only (5.5%) received training in mental health during previous year, While the mean time (in hours) spent in workshops or seminars for mental health care during the previous year was (0.5 ± 1.7) hrs. while, (70.9%) of the participants were poorly overall adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression and (74.5%) had bad prescriptions of antidepressant medications. Regarding the barriers that face family physicians to care of depressed patient, (82%) of the participants admitted low confidence in overall management, (89%) admitted patient reluctance to see mental health professional and (80%) of the physician admitted inadequate time for counseling or health education as organizational barriers. There was statistically significant relationship between adherence to the Egyptian guidelines about prescribing antidepressant medications and qualification (p=0.043) and receiving training in mental health during previous year (p=0.014).

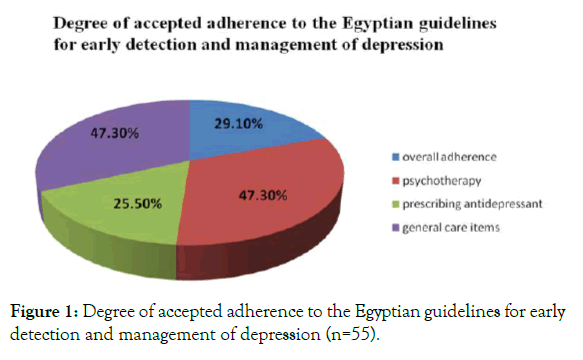

Logistic regression analysis illustrates that physician qualification and number of mental health consultations during the previous year had significant linear association with adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression. (P=0.005, 0.009 respectively) as per Figure 1.

Figure 1. Degree of accepted adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression (n=55).

Table 1 illustrates that the mean age of the participants was 32 years old with predominance of females (80%). Only (5.5%) received training in mental health during previous year. While, the mean time (in hours) spent in workshops or seminars for mental health care during the previous year was (0.5 ± 1.7) and the mean number of mental health consultations during the previous year was (60.2 ± 57.6) session.

| Variables | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|

| (n=55) | ||

| Gender: | ||

| Female | 44 | 80 |

| Male | 11 | 20 |

| Age (in years) (Mean ± SD) | 31.5273 | ± 3.915 |

| 25 | 24 | 43.6 |

| 30- | 29 | 52.7 |

| >40 | 2 | 3.6 |

| Qualification (Under training program) | ||

| Diploma | 9 | 16.4 |

| Master degree | 21 | 38.2 |

| MD | 25 | 45.5 |

| Years of experience | ||

| ≤ 5 years | 24 | 43.6 |

| > 5 years | 31 | 56.4 |

| Receiving training in mental health during previous year | 3 | 5.5 |

| Number of depressed patients seen over the last year (Mean ± SD) | 58.3 ± 62.1 | |

| Amount of time (in hours) spent in workshops or seminars for mental health care during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 0.5 ± 1.7 | |

| The number of articles read about major depression during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 3.3 ± 2.9 | |

| The number of mental health consultations during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 60.2 ± 57.6 | |

| The number of times received orientation about antidepressants by a pharmaceutical company representative during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 4.0 | |

| The number of requests for a specialty referral or for antidepressant medications during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 13.8 ± 23.6 | |

| Need for changing or improving the way of caring for depression | 55 | 100% |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the study group and training received (n=55).

Table 2 illustrates that (82%) of the participants considered that low confidence in overall management, (89%) considered that Patient reluctant to see mental health professional is the main barrier related to patient barriers. While, (80%) of the participants considered that inadequate time to provide counseling or health education is the main barrier related to organizational barriers.

| Physician barrier | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Low confidence in overall management. | 45 | 81.8 |

| Low confidence in treatment with medications. | 43 | 78.2 |

| Low confidence in treatment with counseling. | 41 | 74.5 |

| Patient barrier | ||

| Patient reluctant to see mental health professional. | 49 | 89.1 |

| Patient reluctant to take antidepressant medication. | 47 | 85.5 |

| Medical problems were more pressing. | 44 | 80 |

| Patient concern about medication side effects. | 42 | 76.4 |

| Symptoms may be explained by other medical illness. | 37 | 67.3 |

| Patient or family reluctant to accept diagnosis. | 30 | 54.5 |

| Incomplete knowledge of treatment of depression. | 34 | 61.8 |

| Incomplete knowledge of diagnostic criteria. | 27 | 56.4 |

| Not responsible for treatment. | 21 | 49.1 |

| Lack of effective treatments. | 20 | 36.4 |

| Low confidence for diagnosis. | 18 | 32.7 |

| Not responsible for recognition. | 14 | 25.5 |

| Organizational barrier | ||

| Inadequate time to provide counseling or health education. | 44 | 80 |

| Appointment time too short for adequate history. | 39 | 70.9 |

| Poor reimbursement for treatment | 34 | 61.8 |

| Insurance coverage limited treatment options | 32 | 58.2 |

| Mental health professionals not affordable. | 30 | 54.5 |

Table 2: Barriers to care of depressed patients (n=55).

Table 3 illustrates that there were statistically significant relationship between adherence to the Egyptian guidelines about prescribing antidepressant medications and qualification (p=0.043) and receiving training in mental health during previous year (p=0.014).

| Scoring | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (%) | |||

| Poor (41) | Accepted (14) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 33 (80.5%) | 11 (78.6%) | 1 |

| Male | 8 (19.5%) | 3 (21.4%) | |

| Age (in years) | |||

| 25 | 18 (43.9%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.903 |

| 30 | 21 (51.2%) | 8 (57.1%) | |

| >40 | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Qualification | |||

| Diploma | 9 (22.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.043* |

| Master degree | 17 (41.5%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| MD | 15 (36.6%) | 10 (71.4%) | |

| Years of experience | |||

| ≤ 5 years | 18 (43.9%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.946 |

| > 5 years | 23 (56.1%) | 8 (57.1%) | |

| Receiving training in mental health during previous year | |||

| Didn’t receive | 41 (100.0%) | 11 (78.6%) | 0.014* |

| Received | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | |

| Number of depressed patients seen over the last year (Mean ± SD) | 62.6 ± 62.7 | 45.4 ± 63.9 | 0.16 |

| Amount of time (in hours) spent in workshops or seminars for mental health care during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 0.4 ± 1.8 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 0.169 |

| The number of articles read about major depression during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 4.0 ± 3.5 | 0.452 |

| The number of mental health consultations during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.053 |

| The number of times received orientation about antidepressants by a pharmaceutical company representative during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 4.3 | 0.9 ± 3.2 | 0.494 |

| The number of requests for a specialty referral or for antidepressant medications during the preceding year (Mean ± SD) | 14.8 ± 22.6 | 11.1 ± 26.8 | 0.092 |

| Need for changing or improving the way of caring for depression | 41 (100.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | |

| *Statistically significant at p<0.05 | |||

Table 3: Relation between adherence to the Egyptian guidelines about prescribing antidepressants medications and socio-demographic data.

Table 4 shows the Logistic regression analysis illustrates that the qualification and number of mental health consultations during the previous year had significant linear association with adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression. (P=0.005, 0.009 respectively), the higher level of qualification and the higher number of mental health consultations, the higher adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression (β =2.167, 2.136 respectively).

| Variables | Β | S.E. | Wald | P value | OR | 95% C.I for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||||

| Qualification | 2.167 | 0.78 | 7.79 | 0.005* | 8.74 | 1.91 | 40.01 |

| Number of articles read about major depression during the preceding year | 1.653 | 0.92 | 3.23 | 0.072 | 5.22 | 0.86 | 31.65 |

| Number of mental health consultations during the preceding year | 2.136 | 0.82 | 6.83 | 0.009* | 0.12 | 0.024 | 0.59 |

| Constant | -5.059 | 1.93 | 6.86 | 0.009* | 0.006 | ||

| * Statistically significant at p<0.05 | |||||||

Table 4: Logistic regression for predictors of adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for Early Detection and Management of Depression.

The current study is a cross-sectional study was conducted on 55 family physicians under training in (Diploma, Master degree and MD) working in academic family practice centers, the mean age of family physicians was 32 years old with predominance of female (80%). (45.5%) were MD candidate, (38.2%) were master and (16.4%) were diploma. Meredith LS et al. [7] stated that the mean age of the participants was 44years old, 36% were female and 78% were board certified. While, Hashim H, in Saudi Arabia [8] stated that the mean age of the participant was 39 years old with average years of experience were 13 years and 54% have master degree. The difference between the results could be due to difference in sample size and the limited number of postgraduate physicians in the academic family medicine department.

Regard adherence to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression, (70.9%) of the family physicians were poorly overall adherent to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression and (74.5%) of family physicians were poorly adherent to prescribing antidepressant medications guidelines. These results disagreed with that found by Meredith et al. [7] in Pre-intervention results showed that 73.3% of physicians answered correctly about overall knowledge of depression according to the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality practice guidelines for depression, 77.1% answered correctly about prescribing antidepressants. Our results were inconsistent with that studied by Manal Saeed and Louise McCall in Abu Dhabi [9] in 2006 which showed that 50.6% of family physicians answered correctly the questions on depression according to the British clinical practice guidelines. Whereas, Smolder M et al. [10] showed that 40% of family physicians were good adherent to the Dutch primary care guidelines for diagnosis of depression, 19% of family physicians provided appropriate pharmacological treatment for depressed patients.

Discrepancy between the results of the current study and the above mentioned results could be due to difference in years of experience of family physicians, who work in family practice centers, difference of qualification and patient flow or lack of knowledge about diagnosis and management of depression according to the guidelines due to lack of training courses for family physicians about mental health problems or difference in used guidelines.

Regard training of mental health, only 5.5% of family physicians in the present study received training of mental health during previous year and the mean time (in hours) spent in workshops or seminars for mental health care during previous year was (0.5±1.7) hours.

These results were inconsistent with Meredith LS et al. [7] who reported that family physicians in their study spent about 8hours of their time in CME a continuing medical education for mental health; this could be due to different continuous medical education programs between countries. Also, our results were not in accordance with Manal Saeed and Louise McCall in Abu Dhabi [9] who stated that 85% of family physicians in the study had prior training of mental health.

While, Hashim H Tabuk area Saudi Arabia [8] stated that 64% of the participants received training courses in mental health. This dissimilarity could be due to more interest of family physicians to receive training courses related to chronic diseases as diabetes and hypertension more than mental health diseases or family physician’s belief that they are not accountable for care provided to psychiatric problems.

Regarding barriers that face family physicians to diagnose and manage depressed patients, the results of the present study showed that (82%) of the family physicians considered that low confidence in overall management of depression which was the main physician related barriers. While, (89%) considered that patient reluctance to see mental health professional was the main patient related barriers and (80%) considered that inadequate time to provide counseling or health education was the main organization related barriers.

The results of our study regarding physicians’ barriers differ from a study done by William JW et al. [11] which showed that 64% of family physicians admitted low confidence in treatment with counseling followed by 17% mentioned low confidence in overall management representing both diagnostic and treatment aspects were the main barriers related to physician barriers. But the results in the current study regarding patient and organizational barriers agreed with William JW et al. [11] which showed that patient reluctance to see mental health specialist and inadequate time to provide counseling or health education were the main patient and organization barriers (54% and 64%) respectively. This difference could be due to different health systems, different continuous medical education programs of physicians, or self-assessment methodology in a non-blame culture which facilitate admitting deficiencies and pitfalls.

Our results were in accordance with Hashim H [8] who stated that the main barriers that face primary health care physicians in diagnosing and managing depressed patients in the Tabuk area of Saudi Arabia were incomplete knowledge for managing depressed patient (17.3%), patient denial to accept diagnosis (45.3%), and inadequate time to provide counseling (53.3%), that were related to physicians, patient and organization respectively.

The dissimilarity related to physicians’ barriers may be due to the difference in the level of experience, lack of training courses of mental health to family physicians, or lack of the communication style used in consultations such as assessing suicide risk or advising about taking medication. While, the similarity related to organizational and patient barriers may be due to increased workload seen in family practice centers in a certain time or lack of adequate number of family physicians.

When describing the relation between adherence of family physicians to the guidelines for early detection and management of depression and socio-demographic data, there was a positive significant correlation with qualification and time spent in work shops or seminars for mental health care (p=0.011 and p=0.047 respectively). Also, there was a positive significant correlation between adherence to the guidelines about prescribing antidepressant medications and qualification and receiving training in mental health (p=0.043 and p=0.014 respectively). The results of the current study were partially agreed with Manal Saeed and Louise McCall in Abu- Dhabi [9], showed that the adherence of family physicians to the guidelines for diagnosis and management of depression positively correlate with training of mental health (p=<0.01). But, the results were inconsistent with Meredith et al. [7] who stated that physicians participated in the study were significantly read more articles about depression (p< 0.01) and were oriented by pharmaceutical companies about antidepressant medications (p<0.01). The dissimilarity could be due to low confidence of family physicians in the present study for diagnosis and management of depression due to system difference or system failure to address physician needs.

Our study reveals that most of the family physicians included in the study were poorly adherent to the Egyptian guidelines for early detection and management of depression. So, Quality-improvement efforts need to address barriers to best practice and knowledge gaps about early detection and management of depression. Improving the quality and integration of mental health referral services is necessary for improving outcomes for patients with depression.

Citation: Saad MM, Abdo HA, Metwally TM (2020) Assessment of Family Physician’s Adherence to the Egyptian Guidelines for Early Detection and Management of Depression in Family Practice Centers -Suez Canal University. Fam Med Med Sci Res 9: 254. doi:10.35248/2327-4972.20.9.254.

Received: 22-Jan-2020 Accepted: 14-Aug-2020 Published: 21-Aug-2020 , DOI: 10.35248/2327-4972.20.9.254

Copyright: © 2020 Saad MM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited