Maternal and Pediatric Nutrition

Open Access

ISSN: 2472-1182

ISSN: 2472-1182

Research Article - (2025)Volume 10, Issue 1

Objective: The purpose of the study is to assess magnitude of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antennal care follow-up at Yabello general hospital in Pastoralist Borena Zone from July-August, 2019.

Method: A hospital based cross-sectional study design was employed among 265 pregnant women attending antenatal care at Yabello general hospital from June 17-August 16 2019. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select two hundred sixty-five study subjects. The first study subject was chosen randomly by simple random sampling method blindly picking one of two using pieces of papers named for the first two visitors. The sampling interval (K) calculated to be 2, and then, every second pregnant woman who attending antenatal care was recruited. Socio-demographic, maternal nutrition, information and obstetric and medical characteristics were assessed. Hemoglobin value, stool examination, HIV and syphilis test results were collected from their regular laboratory tests. Blood film was conducted for pregnant women who had signs and symptoms and whose hemoglobin value less than the established cut of values and data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 software

Results: Magnitude of anemia with median hemoglobin value were (11.10 g/dl ± 1.66); majority 46 (63.9%) had mildly anemia, 24 (33.3%) moderate and 2 (2.8%) were severe anemia. Urban dwellers women (AOR, 95% CI: .18 (. 05-.64)), for those who had abortion before current pregnancy (AOR, 95% CI: 3.08 (1.17-8.13)); coffee/tea drinking immediately after meal (AOR, 95% CI: 4.39 (1.82-10.59), and who had excessive menstrual bleeding before current pregnancy were (AOR, 95% CI: 3.39 (1.47-7.84)) and mid-upper arm circumference less than 23 cm (AOR, 95% CI: 6.27 (1.15-14.30)) were found to be independent predictors of anemia among pregnant women.

Conclusion: Anemia in study area among pregnant women in Ethiopia was higher as compare with similar study elsewhere. Malnutrition, abortion, excessive bleeding and nutrition interaction with other inhibitors like coca cola, tea and coffee immediately after meals were independent predictors for anemia.

Magnitude; Anemia; Antenatal care; Yabello hospital; Borena; Ethiopia

ANC: Antenatal Care; CSA: Central Statistical Agency; EDHS: Ethiopian Demography and Health Survey; HGB: Hemoglobin; HSDP: Health Sector Development Program; IDA: Iron Deficiency Anemia; IFAS: Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation; ITN: Insecticide Treated Bed Net; MUAC: Mid-Upper Arm Circumference; RBCs: Red Blood Cells; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Science; SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa

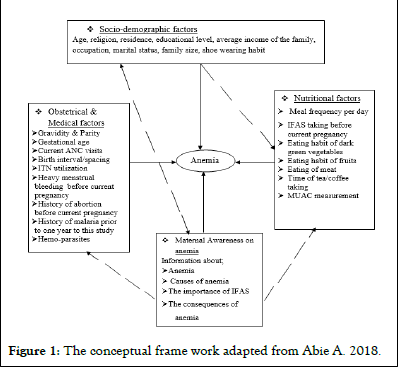

Anemia is defined as a condition in which the number and size of red blood cells and/or the concentration of hemoglobin falls below an established normal cut-off value, and as a result it impaired oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells to the tissues and carbon dioxide from the tissues to the lung [1]. Anemia during pregnancy is a global public health problem which affecting the population of both developed and developing countries with various type and magnitudes and which is responsible for the occurrences of major negative consequences on the human health, the social and the economic development of the countries [2]. During pregnancy, the concentration of hemoglobin decreases from the normal with hemo-dilution due to the increasing of the plasma volume in the circulating blood, and this condition was increase the needs of iron and other nutrients by the body three to six times more than the normal condition for both the mothers and fetus [3-5]. The causes for the occurrences of most anemia during pregnancy include; pregnancies that are closed together, being illiterate, had anemia before the current pregnancy, no eating of enough foods that are rich with iron, poor absorption of iron by the body, parasitic infections, parity, gravidity, poverty, culture, infections, less awareness about anemia, excessive blood loss during pregnancy poor health seeking behavior and so on [6-8]. The occurrence of anemia during pregnancy is preventable and reversible when it occurs due to deficiencies of nutrients particularly, micronutrients, vitamins and proteins and adverse effects of smoking on vitamin C, vitamin B12, folic acid and vitamin A, and therefore, according to Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO), anemia during pregnancy is defined as the concentration of hgb. less than 11 g/dl [7-9]. The magnitudes of anemia among pregnant women vary from countries to countries due to socially, geographically and economic status of the countries, and hence, in Sub-Saharan Africa countries the magnitude of anemia among pregnant women is 57.1%, in South-East Asia 48.2%, and this magnitude is twice as common as in America 21.1% and Europe 25.1% (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The conceptual frame work adapted from Abie A. 2018.

The study aimed to assess magnitude of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women attending antennal care followup at Yabello General Hospital in Pastoralist Borena Zone, Ethiopia from July-August, 2019. A hospital based crosssectional study design was applied.

The source population for this study was all pregnant women with the age between 15 to 49 years’ old who live in Yabello town and its catchment area. The study population was pregnant women who attending antenatal care in Yabello general hospital and study subjects were pregnant women who give full information for research team. Inclusion criteria was a pregnant woman who living in the catchment area and able to respond to the interview whereas exclusion criteria were a pregnant woman who severely ill and unable to respond to the interview and those who referred from other health facilities.

Sampling technique

Systematic and simple random sampling technique was used. The first study subject was chosen simple random sample by blindly picking one of two using pieces of papers named for the first two visitors. The sampling interval (K) calculated to be 2, and then, every second pregnant woman who attending antenatal care was recruited.

Data collection procedure: Data was collected using a face to face interview and MUAC measurement by trained duty-off midwife nurses at the ANC clinic and the results of stool investigation, the value of hgb. and PHICT (HIV) were collected by duty-off assigned laboratory technologists in the laboratory and recorded on to the corresponding questionnaires immediately after the final results were approved by the laboratory technologists. A blood smear was conducted to investigate the morphology of RBCs for those whose hgb. value was less than the established cut-off value (<11.0 g/dl).

Statistical analysis: Data was entered in to Epi-Info version 7.0 and then exported to SPSS Software Version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were done and summarized by frequencies proportions for categorical predictors. Variables with p<0.25 in a binary logistic regression were subjected to a multivariate logistic regression to control the possible confounding effects of other predictors and the strength of association was estimated using odds ratio with p<0.05 at 95% confidence interval.

Data quality management

He questionnaire is adapted from prior related studies and modified to the context of the study area and was translated in to local languages by whom, who is familiar with both languages and back to English. A pre-test was done on 5% with similar population of non-pregnant women in outpatient department at Yabello general hospital to check the understandability of the questionnaire. Data collectors were oriented on data collection tools and the procedures. In the laboratory, the quality of results was ensured through appropriate samples collection and analysis by experienced laboratory personnel. Samples were analyzed using internationally recommended HemoCue-301 hgb. analyzer and Olympus microscope. Appropriate standard operating procedures during sample collection and investigations were followed and completeness of data was checked by supervisor and principal investigator in a daily basis. The value of hgb. was adjusted for altitude and trimesters using WHO hgb. adjustment factors.

Sample size determination

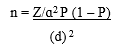

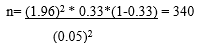

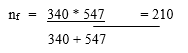

The sample size was determined using both single population proportion formula by computing the proportion of anemia among pregnant women from Arba Minch was 32.8%, 5% of margin of error and 95% confidence interval and a double population proportion formula using Stat-calc Epi Info statistical software version 7.0 with the following assumptions: Confidence level =95%, power =80 %.

Sample size determination for the first objective

Assumption

Z/α(Confidence level) at 95%, which is 1.96, P is the proportion of anemia among pregnant women which is assumed to be 32.8%, d (margin of error) which is 5% 185,980 887.

Since the total population is less than 10,000, the final sample size needs to be corrected using the correction formula:

Where; nf=the desired sample size (when the study population is less than 10,000), n=the desired sample size (when the study population is greater than 10,000, N=the average pregnant women who is expected to visit the ANC during the study period of two months is 547 (YGH, HMIS March to April report 2019).

The final sample size including 10% non-response rate is calculated to be 231.

Sample size determination for second objectives

The sample size for the second objective was calculated using double population proportion formula using the Statcalc of Epi Info statistical software version 7.0 with the following assumptions: Confidence level=95%, Power=80%, the ratio of unexposed to exposed 1.5 (Table 1).

| Variables | AOR | Anemia | Sample size | |

| Exposed | Non-exposed | |||

| HIV infection | 2.72 (1.04-7.23) | 8% | 42% | 120 |

| Previous malaria attack | 1.70 (1.40-9.33) | 58.70% | 47.00% | 260 |

| No iron supplementation | 1.96 (0.85-4.45) | 36.70% | 63.30% | 148 |

| No information about anemia | 2.16 (0.9-5.16) | 31.70% | 68.30% | 136 |

Table 1: Sample size calculation from prior related studies for some selected factors associated with anemia among pregnant women attending ANC at Yabello general hospital from July to August 2019.

The maximum sample size that was obtained from the second objective is 260; therefore, this sample is the larger sample size than the sample size from the first objective which was 231, therefore the final sample size that used for this study was the sample size that obtained from the second objective (260).

A total 265 pregnant women were participated in the study with 100% response rate. The mean age was (23.77 ± 4.91). Look table 2 for more detail).

| Variables | Categories | Anemic | Total (%) | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Age | 15-19 | 19 (23.2) | 63 (76.8) | 82 (30.9) |

| 20-24 | 29 (26) | 81 (73.6) | 110 (41.5) | |

| 25-29 | 17 (67.3) | 35 (32.7) | 52 (19.6) | |

| 30-34 | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) | 14 (5.3) | |

| 35-39 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (2.3) | |

| 40-44 | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | |

| Address | Urban | 25 (15.4) | 137 (84.6) | 162 (61.1) |

| Rural | 47 (44.6) | 56 (54.4) | 103 (28.9) | |

| Religion | Protestant | 28 (25.5) | 82 (74.5) | 110 (41.5) |

| Muslim | 11 (17.7) | 51 (82.3) | 62 (23.4) | |

| Orthodox | 7 (14.9) | 40 (85.1) | 47 (17.7) | |

| Waqefeta | 26 (56.5) | 20 (43.5) | 46 (17.4) | |

| Educational level | Illiterate | 43 (41.3) | 61 (58.7) | 104 (39.2) |

| Read and write | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | 19 (7.2) | |

| Primary/high school | 14 (15.9) | 74 (84.1) | 88 (33.2) | |

| College | 8 (14.8) | 46 (85.2) | 54 (20.4) | |

| Marital status | Married | 70 (27.1) | 188 (72.9) | 258 (97.4) |

| Not married | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Family size | 1-2 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 (1.1) |

| 3-4 | 22 (22.4) | 76 (77.6) | 98 (37.0) | |

| 5-6 | 15 (22.4) | 52 (77.6) | 67 (25.3) | |

| 6 and above | 32 (34.8) | 60 (65.2) | 92 (35.7) | |

| Monthly average income | <1000 EB | 40 (44.4) | 50 (55.6) | 90 (33.9) |

| 1001-2000 EB | 6 (25.0) | 18 (75.0) | 24 (9.1) | |

| >2000 EB | 26 (17.2) | 125 (82.8) | 151 (57.0) | |

| Occupation | House wives | 49 (31.4) | 107 (68.6) | 156 (58.9) |

| Daily laborer | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Gov. employee | 7 (13.2) | 46 (86.8) | 53 (20.0) | |

| Merchant | 15 (27.8) | 39 (72.2) | 54 (20.4) | |

Table 2: Anemia and socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

Magnitude and Severity of Anemia

Overall magnitude of anemia among the studied participants was 27.2% with the media hemoglobin range (11.10 g/dl ± 1.66). Regarding the morphologic appearance of the red blood cells 25(9.4%) pregnant women were with micro-cytosis (smaller size than the normal red blood cells size).

Anemia and nutrition status: One hundred sixty-six (62.6%) participants had meal frequency 3 and + per day during study period. Among them 32 (19.3%) were anemic, 157 (59.2%) who used to drink coffee/tea immediately after meal had mild anemia, 40 (25.5%) were moderate anemia, and 24 (15.3%) were severe anemia Tables 3 and 4 and Figures 2 and 3.

| Variables | Categories | Anemic | Total (%) | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Meal freq./ day | Once per day | 9 (36.0) | 16 (64.0) | 25 (9.5) |

| Twice per day | 31 (41.9) | 43 (58.1) | 74 (27.9) | |

| Three times/day | 32 (19.3) | 134 (80.7) | 166 (62.6) | |

| Coffee/tea drinking immediately after meal | Yes | 61 (38.9) | 96 (61.1) | 157 (59.2) |

| No | 11 (10.2) | 97 (89.8) | 108 (40.8) | |

| Green leafy vegetable consuming status | Every day | 3 (13.0) | 20 (87.0) | 23 (8.7) |

| Once per week | 33 (22.8) | 112 (77.2) | 145 (54.7) | |

| Once per month | 22 (30.6) | 50 (69.4) | 72 (27.2) | |

| Not at all | 14 (66.0) | 11 (44.0) | 25 (9.4) | |

| Fruit consuming status | Every day | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) |

| Once per week | 28 (10.6) | 92 (34.7) | 120 (35.3) | |

| Once per month | 18 (7.0) | 67 (25.3) | 85 (32.3) | |

| Not at all | 25 (9.4) | 32 (12.1) | 57 (21.5) | |

| Meat eating habit | Every day | 0 | 4 (100.0) | 4 (1.5) |

| Once per week | 39 (25.2) | 116 (74.8) | 155 (58.5) | |

| Once per month | 29 (29.6) | 69 (70.4) | 98 (37.0) | |

| Not at all | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (3.0) | |

Table 3: Anemia and maternal nutrition status.

| Variables | Categories | Anemic | Total (%) | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| Information about anemia | Yes | 27 (15.8) | 144 (84.2) | 171 (64.5) |

| No | 45 (47.9) | 49 (52.2) | 94 (35.5) | |

| IFAS | Yes | 42 (31.1) | 93 (68.9) | 135 (50.9) |

| No | 30 (23.1) | 100 (94.7) | 130 (49.1) | |

| Importance of IFAS | Yes | 23 (25.6) | 67 (74.4) | 90 (34.4) |

| No | 49 (28.0) | 126 (72.0) | 175 (66.0) | |

| Problem associated with anemia during pregnancy | Yes | 31 (24.2) | 97 (75.8) | 128 (48.3) |

| No | 41 (29.9) | 96 (70.1) | 137 (51.7) | |

Table 4: Distribution of anemia with maternal information characteristics of pregnant women attending antenatal care at Yabello general hospital 17 June-16 August 2019.

Figure 2: Percentage of anemia by severity among anemic pregnant women (n=72).

Figure 3: Red blood cells morphologic distribution among anemic pregnant women (n=72).

Obstetric and medical characteristics:

One hundred four (39.2%) participants had no previous information about the importance of Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (IFA), almost 135 (50.9%) respondents were supplemented with IFA during their ANC visits. One hundred five (39.6%) participants were not using any methods of contraceptive before the occurrence of current pregnancy. Two hundred seventeen (81.8%) had abortion before the occurrence of the current pregnancy. Two hundred five (77.4%) had no malaria history prior to one year of the study period. 9 (3.3%) participants who had infected with intestinal parasite (amoeba) of this, 7 (2.6%) of the were anemic and 4 (1.5%) and 3 (1.13%) respondents were mild and moderate anemic respectively (Table 5).

| Variables | Categories | Anemic | Total (%) | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | |||

| IFAS during ANC visits | Yes | 42 (31.1) | 93 (68.9) | 135 (50.9) |

| No | 30 (23.1) | 100 (76.9) | 130ÃÃÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂÃÃÂÂÂÂÃÂÂÂÂ (49.1) | |

| Gravidity | Prim-gravidity | 28 (24.6) | 86 (75.4) | 114 (43.0) |

| Multi-gravidity | 44 (29.1) | 107 (70.9) | 151 (57.0) | |

| OC usage before current pregnancy | Yes | 17 (17.0) | 90 (84.1) | 107 (40.4) |

| No | 55 (33.3) | 103 (65.2) | 158 (59.6) | |

| History of malaria | Yes | 13 (28.3) | 43 (71.7) | 60 (22.6) |

| No | 55 (26.8) | 150 (73.2) | 205 (77.4) | |

| Abortion before current pregnancy | Yes | 23 (51.1) | 22 (48.9) | 45 (17.0) |

| No | 49 (22.3) | 171 (77.7) | 220 (83.0) | |

| Heavy menstrual bleeding before current pregnancy | Yes | 32 (50.8) | 31 (49.2) | 63 (23.8) |

| No | 40 (19.8) | 162 (80.2) | 202 (76.2) | |

| Gestational age | First trimester | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | 23 (8.7) |

| Second trimester | 31 (20.8) | 118 (79.2) | 149 (56.2) | |

| Third trimester | 34 (35.6) | 59 (63.4) | 93 (35.1) | |

| No of ANC visit | Once | 24 (20.0) | 96 (80.0) | 120 (45.3) |

| Twice | 29 (35.6) | 60 (64.4) | 89 (33.6) | |

| Three times | 19 (33.9) | 37 (66.1) | 56 (35.1) | |

| MUAC | <21 cm | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | 19 (7.2) |

| 21-23 cm | 55 (27.1) | 148 (72.9) | 203 (76.6) | |

| >21 cm | 7 (16.3) | 36 (83.7) | 43 (16.2) | |

| Syphilis | Positive | 2 (25) | 6 (75) | 8 (3.0) |

| Negative | 70 (27.2) | 187 (72.8) | 257 (97.0) | |

| HIV | Positive | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 4 (1.5) |

| Negative | 70 (26.8) | 191 (73.2) | 261 | |

| Stool exam. | Bacillary | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (3.0) |

| Amoebiasis | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 9 (3.4) | |

| No parasite | 65 (24.5) | 183 (75.5) | 248 (93.6) | |

Table 5: Anemia, obstetric and medical characteristics study participants.

Associated factors and anemia among pregnant women

In a binary logistic regression analysis: education, income, abortion, heavy menstrual bleeding, gestational age, family size, meal frequency per day, drinking of coffee immediately after meal and no supplementation of iron-folic acid during pregnancy were statistically significant associate with anemia during pregnancy (p<0.25) (Tables 6-8).

| Variables | Categories | Anemic | COR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Educational status | Illiterate | 43 (41.3) | 61 (58.7) | .247 (.106-.575)* | 0.001 |

| Read and write | 7 (36.8) | 12 (63.2) | .298 (.090-.987) | ||

| Primary/HS | 14 (15.9) | 74 (84.1) | .919 (.358-2.361) | ||

| College | 8 (14.8) | 46 (85.2) | 1 | ||

| Address | Urban | 25 (15.4) | 137 (84.6) | 4.599 (2.585-8.184) | 0 |

| Rural | 47 (45.6) | 56 (54.4) | 1 | ||

| Family size | 1-2 | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | .889 (.199-3.961) | 0.061 |

| 3-4 | 22 (22.0) | 78 (78.0) | 1.842 (.972-3.493) | ||

| 5-6 | 28 (27.7) | 73 (72.3) | 1.849 (.903-3.787) | ||

| >6 | 19 (32.8) | 39 (67.2) | 1 | ||

| Occupation | House wives | 49 (31.4) | 107 (68.6) | .840 (.423-1.666) | 0.067 |

| Daily laborer | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | .385 (.023-6.550) | ||

| Gov. employee | 7 (13.2) | 46 (86.8) | 2.527 (.936-6.825) | ||

| Merchant | 15 (27.8) | 39 (72.2) | 1 | ||

| Average monthly income | <1000 EB | 40 (44.4) | 50 (55.6) | .260 (.144-.470) | 0 |

| 1001-2000 EB | 6 (25.0) | 18 (75.0) | .624 (.226-1.723) | ||

| >2000 EB | 26 (17.2) | 125 (82.8) | 1 | ||

Table 6: Binary logistic regression analysis for socio-demographic factors associated with anemia.

| Variable | Categories | Anemic | COR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Abortion history | Yes | 21 (43.8) | 27 (56.2) | .274 (.141-.533) | 0 |

| No | 51 (23.5) | 166 (76.5) | 1 | ||

| Contraceptive usage before | Yes | 17 (17.0) | 83 (83.0) | 2.827 (1.531-5.219) | 0.001 |

| No | 55 (33.3) | 110 (66.7) | 1 | ||

| Heavy menstrual bleeding | Yes | 28 (43.8) | 36 (56.2) | .239 (.131-.437)* | 0 |

| No | 44 (21.9) | 157 (78.1) | 1 | ||

| Inter-pregnancy interval | 0 | 30 (11.3) | 89 (33.6) | .364 (.119-1.117) | 0.002 |

| 1-3 | 10 (3.8) | 28 (10.6) | .152 (.025-.940) | ||

| 4-6 | 28 (10.6) | 48 (18.1) | .309 (.087-1.092) | ||

| >6 | 4 (1.5) | 28 (10.6) | .167 (.053-.524) | ||

| Gestational age | First trimester | 7 (30.4) | 16 (69.6) | 1.317 (.493-3.521) | 0.008 |

| Second trim | 31 (20.8) | 118 (79.2) | 2.194 (1.230-3.912) | ||

| Third trime | 34 (35.6) | 59 (63.4) | 1 | ||

| ANC visits | First | 24 (20.0) | 96 (80.0) | 2.054 (1.008-4.184) | 0.045 |

| Second | 29 (32.6) | 60 (67.4) | 1.062 (.523-2.159) | ||

| Third and above | 19 (33.9) | 37 (66.1) | 1 | ||

Table 7: Binary logistic regression analysis for medical and obstetric associated factors.

| Variable | Categories | Anemic | COR 95% CI | P-value | |

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Meal frequency | Once/day | 9 (36.0) | 16 (64.0) | .425 (.172-1.047) | 0.001 |

| Twice/day | 31 (41.9) | 43 (58.1) | .331 (.181-.605) | ||

| Three and more | 32 (19.3) | 134 (80.7) | 1 | ||

| Consuming green leafy vegetable | Everyday | 3 (13.0) | 20 (87.0) | 8.485 (1.995-36.093) | 0.004 |

| Once per wk. | 33 (22.8) | 112 (77.2) | 4.320 (1.792-10.414) | ||

| Once / month | 22 (30.6) | 50 (69.4) | 2.893 (1.135-7.371) | ||

| Not at all | 14 (66.0) | 11 (44.0) | 1 | ||

| IFAS | Yes | 42 (31.1) | 93 (68.9) | .664 (.384-1.148) | 0.018 |

| No | 30 (76.9) | 100 (23.1) | 1 | ||

| Coffee/tea drinking | Yes | 66 (42.0) | 91 (58.0) | .178 (.089-.360) | 0 |

| No | 6 (5.6) | 102 (94.4) | 1 | ||

| MUAC | <23 cm | 10 (52.6) | 9 (47.4) | .175 (.052-.587) | 0.017 |

| 21-23 cm | 55 (27.1) | 148 (72.9) | .523 (.22.-1.245) | ||

| >23 cm | 7 (16.3) | 36 (83.7) | 1 | ||

Table 8: Binary logistic regression analysis for nutrition associated factors and anemia.

In multivariate regression analysis results, the pregnant women who were from urban dwellers (AOR, 95% CI: .18 (.05-.64)), abortion before current pregnancy (AOR, 95% CI: 3.08 (1.17-8.13)), coffee/tea drinking status immediately after meal (AOR, 95% CI: 4.39 (1.82-10.59)), excessive menstrual bleeding than usual before the current pregnancy (AOR, 95% CI: 3.39 (1.47-7.84)) and mid-upper arm circumference (AOR, 95% CI: 6.27 (1.15-14.30)) were independent predictors of anemia by controlling other explanatory variables (Table 9).

| Variables | Categories | COR (95% CI), p<0.25 | AOR(95% CI) | p<.05 |

| Address | Urban | 4.599 (2.585-8.184) | .178 (.050-.635)* | .008 |

| Rural | 1 | |||

| Abortion | Yes | .274 (.141-.533) | 3.081 (1.167-8.131)* | .023 |

| No | 1 | |||

| Coffee drinking | Yes | .178 (.089-.360) | 4.394 (1.823-10.589)* | .001 |

| No | 1 | |||

| Excessive menstrual bleeding | Yes | .239 (.131-.437) | 3.394 (1.469-7.844)* | .004 |

| No | 1 | |||

| MUAC | <23 cm | .175 (.052-.587) | 6.274 (1.148-14.298)* | .034 |

| 21-23 cm | .523 (.22.-1.245) | 1 | ||

| >23 cm | .123 (.12.-.245) | 1 |

Table 9: Multivariate logistic regression analysis associated factors with anemia among pregnant women attending ANC at Yabello general hospital 17 June-16 August 2019.

The aim of study was to know the magnitude of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women. According to finding, the overall magnitude of anemia is 27.2%, this is similar when compare with study conducted in the South Nations and Nationalities People of Ethiopia which showed (27.6%); however, the finding is higher than a study conducted in Adama Hospital Medical College (14.9%), North Shoa (10%), Gondar (16.6%), and was slightly higher compared to the national prevalence (23%) and study conducted in China (23.5%). Furthermore, the finding is lower than the study findings conducted in the Arba-Minch hospital (32.8%), Neqemte hospital (52.0%), Kenya (57.0%), South Africa, (57.7%), India (64.0%) and Baghdad (67.0%). The differences might be because of the geographical variations, sampling techniques, software used for data analysis, skill of research teams, information and recall biases. Based up on the classification degree of anemia by WHO among all anemic pregnant women about (63.9%) were mild anemic, 33.3% were moderately anemic and (2.8%) were severely anemic. Our study findings also contradict with the study conducted in Egypt (92.2% mildly anemic, 7.8% moderately anemic and no severely anemic was reported). This variation might be resulted from different geographic location and advancement in quality of ANC and standardized living conditions.

Multiple logistic regression analysis reveals that, the odds of anemia among pregnant women who were urban dwellers (AOR 95% CI: .178 (.050-.635) times less likely compared to the odds of anemia among pregnant women who were rural dwellers. Similar finding of the study was reported from Ambiya health center. This variation could be due to; difference in educational level (55.5% from urban compared to 5.3% from rural; at least with one of educational categories), being informed about anemia and the possible risk factors (46.4%) urban dweller compared to pregnant women from rural (18.1) and being supplemented with IFA during their ANC visit 61.1% and 389% pregnant women from urban and rural respectively.

Among pregnant women who encountered abortion before the current pregnancy, the probability being anemic was 3.081 times higher than pregnant women who did not encounter abortion before the current pregnancy (AOR=95% CI: (1.167-8.131)). This could be resulted because abortion might expose women to loss more blood through prolonged hemorrhage and this condition leads to extra requirements of iron by the body. Study also showed that pregnant women who used to drink coffee/tea immediately after meal were (AOR=95% CI: 4.394 (1.823-10.589) times more likely to be anemic compared to pregnant women who did not drink coffee/tea immediately after meal. The similar study conducted in Durame health center showed similar result. The possible reason could be some chemicals could inhibit non-heme iron absorption by Tannin acid in coffee/tea. According to findings pregnant women with heavy menstrual bleeding than usual before the current pregnancy were (AOR=95% CI: 3.394 (1.469-7.844)) times more affected by anemia compare to pregnant women with normal menstrual bleeding; this finding is similar with the study in Mizan Tepi. Because of excessive loss of blood through menstrual bleeding, the pregnant women might encounter anemia due to the expansion of the blood plasma volume. The odds of anemia among pregnant women with mid-upper arm circumference less than 23 cm were (AOR=95% CI: 6.274 (1.148-14.298) which is lower than odds of similar study conducted in Kenya, Nairobi. In this study the findings show that, age, meal frequency per day, gravidity, not consuming green leafy vegetables, not consuming fruits after meal, history of malaria before the current pregnancy, not using Iron-Folic- Acid (IFA) supplementation and educational level, are not significantly associated with maternal anemia, but they were significantly associated with maternal anemia by other similar studies findings.

The research is intent to assess current status of anemia among pregnant women. Anemia prevalence in study area among pregnant women was moderate as compare with similar study conducted elsewhere. A multitude of external factors can affect the amount of iron available for absorption as either inhibitors or promoters. In this study malnutrition, abortion, excessive bleeding and nutrition interaction with other inhibitors like coca cola, tea and coffee drinking immediately after meals were independent predictors for anemia development. Therefore, health education should be given by health professional to enhance knowledge of pregnant on adequate dietary intake and Iron-folic combination supplement.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Adama Hospital Medical College and subsequent permissions were obtained from line departments and respective health institutions. Data were collected through structured questionnaire after translated into local language from pregnant women attending antenatal care follow up at different private and government higher clinics and Hospital. Verbal informed consent was obtained from participants who visit the facilities during the data collection period. In the informed consent form significant information such as aim of the study, confidentiality of the information and participant’s right to drop and withdraw from study have been explained.

As there are no identifiable details on individual participants reported in the manuscript, consent to publish is not required.

The datasets examined during the current study are available from the both authors corresponding and second authors on sensible inquiry.

As the authors we did not have any competing interest.

Adama Hospital Medical College delivered us financial support for the data collection and related cost. No other fund was obtained for the current

We are proposed and ran study design, data collection, performed data analysis and recruited the manuscript. Third persons had been analytically revised and finalized entire document with imperative contributions. Finally, we both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Dr Godana Arero (MPH in General Public Health, PhD in Nutritional Science) and working at Adama Hospital Medical College as Assistant Professor of nutrition, researcher, consultant and Head Public Health Department. Mr. Kinde Asssefa (BSC in Laboratory Technology) working at Yabello General Hospital, Department of Laboratory as an expert.

We thank Adama Hospital Medical College for funding the study and for the ethical approval. We are also thankful to other line departments and individuals who played important roles in availing necessary information without which this work wouldn’t have been completed. Last, but not least, we also appreciate the contributions of all supervisors, data collectors and study participants for their respective contribution without which the work would not have been appreciated.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Assefa K, Arero G (2025) Anaemia and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Follow-up at Yabellow General Hospital Living in Pastoralist of Borena Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia from July to August, 2019. Matern Pediatr Nutr. 10:248.

Received: 19-Mar-2024, Manuscript No. MPN-24-30262; Editor assigned: 21-Mar-2024, Pre QC No. MPN-24-30262 (PQ); Reviewed: 04-Apr-2024, QC No. MPN-24-30262; Revised: 13-Mar-2025, Manuscript No. MPN-24-30262 (R); Published: 20-Mar-2025 , DOI: 10.35248/2472-1182.25.10.248

Copyright: © 2025 Assefa K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.