Journal of Tourism & Hospitality

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0269

ISSN: 2167-0269

Research Article - (2019)Volume 8, Issue 1

A large number of studies have been done to determine strategies to tackle poverty in Nigerian context, however quite a few focused on marketing approach to the problem. Accordingly, this paper seeks to determine empirically the adoption of marketing mix model for reducing poverty incidence in Nigeria. Quantitative survey research design was adopted for the study. Questionnaire was used to collect data from 240 selected Nigerians who earn below 1 dollar a day in the six geo-political zones of Nigeria. Face and content validities of the questionnaire were ascertained. Reliability of the instrument was supported using Cronbatch alpa test which show 0.84 co-efficient. Logit regression analysis was used to test the hypotheses. Results show that poor quality of poverty alleviation products, poor pricing, poor marketing promotion, poor distribution, poor people, poor processes and poor physical evidence have significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. Improvements in these weak marketing mix variables were recommended in order to improve poverty syndrome in Nigeria.

Poverty alleviation; Programme; Marketing mix; Poverty incidence; Nigeria

Poverty is a global problem. There is no nation that is absolutely free from poverty. What is perhaps arguable is the level at which it afflicts nations. Although poverty syndrome is world-over, the problem appears more acute in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, Latin America and other developing nations [1-5].

In the case of Nigeria, poverty problem appears daunting and this has attracted the attention of the Nigerian government, the international community such as the United Nations, World Health Organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Poverty has also been the focus of many research scholars and also a topical issue in seminars, conferences, symposia and workshops in Nigeria. The major objective has been to determine strategies to reduce or eradicate poverty if possible. Similarly, calls have been made on government to introduce reform measures targeted at poverty scourge reduction in Nigeria. However, measures recommended by most past research scholars and conference resolutions appear to concentrate more on domestic, sectorial, financial and economic reform measures than marketing. Various governments in Nigeria both military and democratic have equally responded to the calls by introducing many reform programmes. For instance, at independence government instituted a farm settlement centre the aim of which was to develop cash and food crops. General Gowon administration also introduced Agricultural Development Programme (ADP) in 1973. Similarly Operation Feed the Nation (OFN) was introduced by General Olusegun Obasanjo administration. Green Revolution came on board between 1979 and 1983 during Shehu Shagari administration. Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida introduced Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) in 1986; Better Life for Rural Women in 1986; National Directorate of Employment (NDE), Directorate of Foods, Roads and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI), Family Economic Advancement Programmes (FEAP). The recent programmes are National Poverty Eradication Programmes (NAPEP) and the Sure-P. Evidently these programmes could not achieve any meaningful results in reducing poverty and this situation seems to have fuelled the growth momentum in research papers trying to address the issue [5-7]. More importantly, studies that focused on poverty alleviation in Nigeria from the marketing perspective seem scarce and are beginning to unfold among contemporary scholars [8-10]. It is on this note that the current paper is designed to provide additional insight on how to improve poverty situation in Nigeria from the marketing perspective.

Statement of the problem

Despite the much acclaimed robust reform measures put in place by government to reduce poverty and the various contributions of the research scholars on strategies to tackle poverty in Nigeria, poverty incidence appear to be rising unabated [7,11-13]. For instance, recent research reports [8,14] show that a large percentage of Nigerian earn less than $1 a day and still have no access to such basic needs as food, housing, drinking water, education, power, and good road network which are taken for granted in developed nations. Life expectancy remains at 55 years. Over 60% of employable youths have no jobs. Many youths have lost their lives while trying to illegally migrate from Nigeria to Europe in search of greener pastures. With the disappointing performance of poverty alleviation program in Nigeria, calls from various scholars on how to deal with poverty situation have continued to receive a heightened attention. Although significant contributions have been made by scholars on measures to reduce poverty situation in Nigeria, only a few have tried to address this problem from the marketing perspective even when research studies show that marketing is a potent tool for selling government programmes. Research in area of marketing approach to poverty reduction in Nigeria remains shallow, elusive and highly under-reported in the main stream literature.

Given this knowledge gap there is the need to explore the degree of marketing influence on poverty reduction in Nigeria. This study would contribute to the discourse, provide additional insights on the marketing solutions to the problem and deepen our knowledge in this domain of inquiry.

Objectives of the study

The objectives of the study include:-

• To determine the influence of poor products’ quality on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• To ascertain the extent of the influence of poor price on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• To assess the influence of poor marketing promotions on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• To analyse the degree of the influence of poor place strategy on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• To ascertain the influence of poor people on poverty incidence in Nigeria.

• To analyze the extent of the influence of poor process on poverty incidence in Nigeria.

• To determine the degree of poor physical evidence on poverty incidence in Nigeria.

Statement of hypotheses

• Poor product quality does not have any significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• Poor price has no significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• Poor marketing promotions do not have any significant influence on the poverty incidence in Nigeria

• Poor place strategy has no significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria

• Poor people do not have any significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria.

• Poor process has no significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria.

• Poor physical evidence does not significantly influence poverty incidence in Nigeria.

Conceptual framework

The nature of poverty: The term “Poverty” has no simple definition. It is a multi-dimensional concept which can be described from different perspectives. Individuals who are born into upper class society cannot even imagine or explain poverty. Sometimes the concept is better explained by the poor who experience it. Narayan, for instance, captured the view of a poor Kenyan man who was asked to define poverty in the following words:

“Don’t ask me what poverty is because you have met it outside my house. Look at the house and count the number of holes. Look at my utensils and clothes I am wearing. Look at my house and write what you see. What you see is poverty”

A number of studies conceptualize poverty as a situation where a person, household, community or nation does not have the basic necessities of life that others around have or enjoy. Poverty affects all aspects of human lives such as the cloth we wear, the foods we eat, and the houses we live in. It also affects our communication, transportation, sanitation, markets facilities, our education and health statuses as well as our general living standards. It can also mean begging for food and clothing. Think of where a man is forced to accept humiliation and insults when he seeks for help. All these are signs of “poverty”.

Okoh [15] defined poverty as a state of deprivation in terms of economic and social indicators such as income, employment, education, health care, access to food, social status, self-esteem and self-actualization. Similarly, Obadan [16] to the poor as those who are unable to obtain an adequate income, find a suitable job, own property or maintain a healthy living standards.

Aku et al. [17] explains poverty from five dimensions of deprivation. These are: (i) those who lack personal physical and basic needs such as food, shelter, clothing, health, education; (ii) those who lack economic power such as income, property, assets, capital and factors of production; (iii) those that lack freedom of full social association (social deprivation). (iv) those that lack access to cultural values, beliefs, knowledge, information (cultural deprivation) and (v) those that lack political voice to participate in decision making that affects their lives. According to the World Bank Report [18], poverty is hunger, lack of shelter, being sick and not being able to go to school, not knowing how to read or write or speak properly, not having a job, fear for the future, losing a child to illness brought about by poor hygiene and lack of finance. It also means powerlessness, lack of representation and freedom.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) adopt the use of Human Development Index (HDI) for measuring the level of poverty in a country. HDI combines life expectancy at birth, educational level and improvement in standard of living as determined by capita income in determining poverty level. As measures of poverty World Development Report [19] uses income level of less than US $ 370 a year or a dollar a day as benchmark for determining poverty.

Although “poverty” is defined in different ways, majority of the authors seem to agree that poverty has four characteristics [6,20-22]. Firstly poverty is absolute. Absolute poverty refers to a serious deficiency or lack of access to basic necessities of life such as food, drinkable water, clothing, medical care, education, employment, communication, transportation and other basic social infrastructures [21-25].

Secondly, poverty is relative. It refers to the economic and social deprivation which an individual, household, group or community or nation suffer when compared to others in the same locality or elsewhere [26]. Thus a person considered rich in rural area may be poor when compared with those living in the urban areas. Nigeria may be considered rich when compared to Togo. However when compared to Germany, it may be considered poor. What is considered poverty level in one country or community may well be the height of well-being in another.

Thirdly, poverty operates in a vicious circle. Poverty begets poverty. Vicious circle of poverty refers to a situation where there is a low level of income and there is a low level of income because there has been little investment or lack of employment [27]. Many people born under this type of environment also raise poor children.

Fourth poverty is subjective. This is based on one’s own judgment of himself. In Nigerian context subjective poverty is caused by government and the governed. On the part of government, corrupt officials misuse the nation’s resources meant for development and poverty alleviation [6]. On the part of the governed, many are lazy and do not simply want to do anything meaningful to get out of poverty. Many are not even employable.

Poverty incidence in Nigeria: For most Nigerians, poverty is endemic and real. By all standards a large percentage of Nigerians has no access to quality foods, housing, health, sanitation, and security [24,25]. Life in Nigeria involves a daily struggle against hunger, malnutrition, electricity, energy crisis, poor medications even drinkable water [6]. In Nigeria there is no social welfare programme to alleviate the condition of the poor. The poor depend largely on relations and friends for sustenance [22].

Evidences from World Development Indicators [WDI], Multidimensional Poverty Index [MPI] and Oxford Poverty Human Development Initiative [OPHI] reveal that Nigeria is third poorest country in the world. 88.59 million of the people presently are living below $1.25 per day and about 93.83 million are living in multidimensional poverty [10]. These figures are still on the increase as more Nigerians are becoming internally displaced from their homes due to the rising insurgencies, terrorist and Fulani herdsmen attacks currently ravaging the country [22]. Poverty incidence in Nigeria is a function of the level at which poverty indices and measures (poor per capita income, poor standard of education and poor living standard) exist in the country.

Past poverty alleviation programmes in Nigeria: Poverty Alleviation Programmes (PAPs) in Nigeria refers to governmentrelated socio-economic programmes targeted at reducing or eradicating poverty in the country. Table 1 below shows some past poverty alleviation programmes in Nigeria.

| S/N | Programmes | President | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Accelerated Food Programme | Gowon | 1973 |

| 2 | Nigerian Agriculture and Co-operative Bank | “ | 1972 |

| 3 | Lake Chad Basin Development Authority | Murtala | 1975 |

| 4 | Agricultural Development Project (ADP) | “ | 1975 |

| 5 | River Basin Development Authority (RBDA) | Obasanjo | “ |

| 6 | Operation Feed the Nation (OFN) | “ | 1976 |

| 7 | Nigerian Export Promotion Council (NEPC) | “ | 1979 |

| 8 | Green Revolution | Shagari | 1979 |

| 9 | Federal Agricultural Co-ordination Unit (FACU) | “ | 1983 |

| 10 | National Directorate of Employment | Babangida | 1986 |

| 11 | Nigeria Export Processing Zone | “ | 1986 |

| 12 | Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) | Babangida | 1986 |

| 13 | Better Life for Rural Women | Babangida | 1986 |

| 14 | Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme | “ | 1986 |

| 15 | Directorate of Foods Roads and Rural Infrastructure | “ | 1989 |

| 16 | National Agricultural Insurance Corporation (N.A.I.C) | “ | 1988 |

| 17 | Back to Land | Buhari | 1983 |

| 18 | People’s Bank of Nigeria | Babangida | 1990 |

| 19 | National Agriculture Land Development Authority (N.A.L.D.A.) | “ | 1991 |

| 20 | Family Economic Advancement Programme (FEAP) | “ | 1997 |

| 21 | National Programme for Food Security | Abdusalam | 1999 |

| 22 | Nigeria Agricultural Co-operative & Rural Development | Obasanjo | 2000 |

| 23 | Root Tuber Expansion Programme (RTEP) | “ | 2001 |

| 24 | Presidential Initiative on Rice, Cassava etc. | “ | 2001 |

| 25 | Vegetable Oil Development Programme | “ | 2001 |

| 26 | TREE Crop Development Project | “ | 2001 |

| 27 | Natural Food Reserve Agency | Yar’Adua | 2008 |

Table 1: Some Past Poverty Alleviation Programmes.

It is worthy of note that despite the pragmatic and lofty programmes designed by government to reduce or eradicate poverty in Nigeria, poverty situation appear daunting and no significant improvement seems to have been recorded [6].

Marketing and poverty alleviation programmes in Nigeria: Recommendations of past studies on how to reduce poverty scourge in Nigeria seem to have been concentrated more on administrative, political, multi-domestic sectorial, financial and economic reform measures and strengthening of public institutions [6] than marketing even when marketing has been widely recognized in the literature as a potent tool for promotion of social causes [9]. It is in this connection that marketing scholars acknowledge marketing mix elements as the strategies for creating, stimulating, facilitating, sustaining and achieving exchange behaviors as well as promotion of social causes such as poverty alleviation. Consumption or exchange behavior is a strong correlate of marketing mix elements [11,28]. It is on this basis that we adopt marketing mix elements as tools for tackling poverty incidence in Nigeria. Arguably, poverty reduction in Nigeria will largely depend on how well these marketing mix elements are formulated to address the socio-economic needs of the poor.

Marketing mix is the combinations of the basic controllable input that constitute the core of an organization’s internal marketing system. Marketing mix is a set of tools that organizations use to achieve their marketing goals in their target markets. Development of the marketing mix elements has received a considerable research attention such that a number of researchers propose different elements of the marketing mix at different times as Table 2 below shows:-

| S/N | Author | Marketing Mix Elements Proposed by Different Scholars |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Borden (1965) | Product planning, pricing, branding, channels of distribution, personal selling, advertising, promotions, packaging; display, servicing, physical handling and fact finding and analysis |

| 2 | McCarthy (1964) | Product, price, promotion and place |

| 3 | Lazer et al (1973) | Goods and services mix ; the distribution mix; communication mix |

| 4 | Booms and Bitner (1980) | To accommodate the service firms, the authors added, people, physical evidence and process to McCarthy’s original 4P’s thus making a total of 7Ps. |

| 5 | Kotler (1986) | Added, political power and public opinion formation to McCarthy’s 4Ps. |

| 6 | Judd (1987) | Added fifth “P” (people) to McCarthy’s 4P’s |

| 7 | Vignals and Davis (1994) | Added “service” to the McCarthy’s original 4P’s |

| 8 | Goldsmith (1999) | Added “participants, physical evidence, process, and personalization. |

Table 2: Marketing Mix Elements.

Although Table 2 shows that there is no consensus among scholars in the literature regarding what constitutes the elements of the marketing mix, there is a fairly strong support for Booms and Bitner’s [29] 7Ps marketing mix framework. Thus in line with the views of other scholars, this study adopted 7Ps marketing mix elements as the framework for reducing poverty incidence in Nigeria.

The relationship between marketing mix elements (7Ps) and poverty incidence in Nigeria product: A product is conceived as anything that the buyer acquires or purchases to satisfy a need or want. It includes physical objects, services, persons, places, organizations, programmes or ideas. As individuals or a household buys food to satisfy hunger drive so also the poor are expected to purchase poverty alleviation programmes (products) to reduce poverty. It is important to understand that unless a product provides satisfaction or solutions to a buyer’s needs or problems, a product becomes ordinary “bolts” and “nuts” and of no use. For it is the satisfaction inherent in a product that drives consumer patronage it. It is in this sense that Onyeke and Nebo [30] define a product as a bundle of benefits. Therefore product in this current study is regarded as all the poverty alleviation programmes many of which are listed in Table 1 which government offers to the poor for attention, acquisition, use or consumption which are expected to reduce or eradicate poverty. This is measurable through the fund government has spent so far on the programme and the perceived benefits the programmes offer to the poor. It can also be measured through quantity and quality of poverty products such as soft loans to investors, basic education for all, primary health care delivery systems, access roads, stable power supply, communication facilities and balanced nutrition to the poor. Others are: provision of employment opportunities to the poor through the establishments and proper funding of small and medium scale industries [31]. In a study conducted by Vinodhini and Kumar [32] and Chao-Chan Wu [33], results established a strong positive relationship between quality of products and sales performance. There is also a strong positive relationship between provision of social infrastructure, employment and poverty reduction in Nigeria [31].

Price: Price is the money paid in exchange for a product. It is a value expressed in terms of money [34,35]. Buyers’ concern for and interest in price is related to their expectations about the satisfaction or utility associated with a product. For the purpose of this study, price is measured in terms of what the poor has to pay in order to obtain poverty alleviation products such as payment of interests and provision of collateral securities on loans. Others prices paid for poverty alleviation are: bills which the poor pay in order to enjoy social amenities such as water, electric, market, hospital, sanitation, business premises, education. Others are food bills and income taxes. Consuegra, Molina and Esteban [36] examined the relationship among price fairness, customer satisfaction and patronage and found a strong positive relationship. Similarly, Nebo and Okolo [37] did a study on the strategies for customer satisfaction on the performance of insurance firms in Enugu metropolis, findings show that insurance premium (price) was a key factor in customer patronage and sales of insurance products.

Promotion: Promotion refers to the marketer’s means of communicating product offerings and marketing programmes and activities to actual and potential customers. Marketing promotion tools are done through the means of advertising, personal selling, sales promotion, publicity, public relations and direct marketing. Marketing communications are potent tool for educating consumers about products benefits and uses as sell as increasing level of patronage and sales performance [38,39]. In this study, the means through which government communicates information about poverty alleviation porgramme are regarded as marketing communications and it is measured by the amount of money government has spent so far on marketing communication tools such as billboards, newspapers, radio, televisions announcements, internet advertisements and the level of awareness created by government on the programmes, the advertisement recall level, intentions to buy poverty alleviation products by the poor. Nebo and Okolo’s [11] study found effective marketing promotion as a strong correlate of customer satisfaction, patronage and sales performance of insurance services.

Place (Distribution): Place also known as distribution is concerned with making products available at the desired time and location using marketing logistics (e.g transportation, storage, inventory, and packaging) and channel members (e.g manufacturers, distributors, retailers and agents). No product or service in an absolute sense is of any value to a customer unless it is made available to him. It is the responsibility of the originator of the product to select and use the appropriate channel to get his products to customers. This is very important as failure to do this means that the customers would not have access to the products. In this study, the distribution channels are the various government outlets, ministries, agencies, banks, insurance firms and on-line tools through which poverty alleviation products are made available to the poor. Various studies have shown that efficient and effective distribution have a strong relationship with customers’ patronage of a product [40-42]. Effective distribution of poverty alleviation products is a measure of the extent to which poverty alleviation products such as soft loans, basic education, primary health care delivery systems, access roads, stable power supply, communication facilities, balanced foods, markets, employment opportunities, good leadership and governance are made accessible to the poor through proper channel of distribution.

People: In this study, people refer to government employees or officials in various ministries, agencies and parastatals who implement poverty alleviation programmes. The quality of poverty alleviation staff (people) is measured in terms of how reliable, empathic, responsible, responsive and sensitive they are to the problems and needs of the poor masses. Various studies have shown that success or failure of services depend on the reliability, assurance, empathy and responsiveness of the individuals who provide them [11,43,44]. Aliyu [31] noted in his study that embezzlement of fund by corrupt officials and insensitivity of government officials to the plights of poor were the major cause of poverty in Nigeria. He discovered that the poor were often neglected in budget allocations due to poor leadership. He lamented that economic and social policies in Nigeria were not designed to lift the poor out of poverty.

Process: This refers to the procedures, mechanism and flow of activities by which a service is acquired. It is seen as a series of steps followed to accomplish a specific task or undertaking. It is the gamut of stages, documentation, explanations, procedures, and rules to be observed while accessing poverty alleviation programmes. For instance, the process to be followed in obtaining poverty alleviation loans may require that the consumer (the poor) submits application letter to the relevant authorities, pays for the application fee, attaches some important documents such as passport-sized photograph, letter of identification, age declaration etc. to the application and returning same to the relevant authorities or agencies within a specified period of time. The application forms to be completed by the customer, the poor in this case, should be simple and easy to understand. The easier and simpler the forms are to complete, the greater the time utility and service accessibility to the customer. A well-trained staff should be used in providing answers to questions usually raised by customers while completing the forms. Narang’s [45] study show that ambiguous and complex service process produce patient’s dissatisfaction in Indian hospital’s service delivery.

Physical evidence: In this study, physical evidence refers to the physical facilities, general conditions of equipment, personnel, communication materials and the environment that facilitate the performance of poverty alleviation services. Examples are equipment, buildings, structures and facilities in public hospitals, schools, power authorities, water corporations, ministries, parastatals, government agencies and conditions of access roads. Holder [46] concluded in his study that physical evidence is an important dimension in the perception of service quality.

Empirical studies

Quite a number of studies have been done to determine the strategies for poverty alleviation in both Nigerian context and countries abroad. By focusing only on the studies done in the Nigerian context, Oloyede’s [7] study revealed that there has been a significant effect of poverty reduction on economic development in Nigeria. However, other studies show that poverty alleviation programmes have been a failure in Nigeria [5,23,47]. Of all the reported causes of the programmes’ failure, corruption was highest. On this note, two opposing schools of thought advocate bidirectional causality between corruption and poverty. The first school of thought championed the malignant infests of corruption as the leading cause of poverty in Nigerian over the years [14,20,22,23,47]. The other school of thought argued otherwise, stating that poverty syndrome has institutionalized the culture of corruption in Nigeria [6]. Regardless of how poverty and corruption affect each other, findings from most extant studies have established that both menace remain and these have been a serious virus wrecking the socioeconomic lives of Nigerians [22].

As it becomes almost impossible for successive government administrations in Nigeria to end poverty, studies suggesting diverse strategies to tackle the problem have continued to receive a heightened attention. While some researchers strongly advocate for socioeconomic reforms, some suggest a paradigmatic shift in how poverty alleviation efforts are made. Amongst the subscribers of the former are: Osahon and Osarobo [20], and Aluko [6], who advocate a total domestic macro and sectorial policy reforms that improve general living standards and access to education, health, transportation, communication and food. Among those who advocate a change in how poverty alleviation programmes are implemented is Adawo [22] who argue that the poor should first be clearly identified before designing products that meets their needs.

Similarly, other scholars offer a participatory approach as a pathway for improving the poverty situation in Nigeria [5,14,23]. They strongly recommended that the poor masses should be involved in the planning, formulation and implementation of the poverty programmes. Additionally, Innocent et al. [14] suggest that the programmes should be made to be in line with the yearnings and aspirations of the poor masses.

Few studies have been able to approach poverty alleviation from the marketing perspective. One of such studies was done by Kehinde [8] who recommended an eight-step process for achieving success in the marketing of poverty alleviation products. The steps include (i) problem statement: recognizing that poverty exists; (ii) use of marketing research to find types and causes of poverty; (iii) generate alternatives to solve the poverty problem; (iv) develop strategies and policies to solve the chosen alternative; (v) implement the developed strategies and policy solutions; (vi) control and evaluation; (vii) harvest results; and (viii) carryout research on the post evaluation results to find out the true and current positions of things. Levinsohn [10] did a similar study titled World Bank’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Approach: Good Marketing or Good Policy? The study show that the poor was not properly identified and there was no significant changes in the well-being of the poor after implementation of programme. Kotler and Levy [48] also called for marketing thinking in providing solutions to poverty situation especially in the third world countries.

Gaps in the reviewed literature

Past studies reviewed so far show that there seem to be a paucity of research focus on the use of marketing strategies for reducing poverty scourge in Nigeria. Specifically, it appears that few studies have been done to (i) determine whether poverty alleviation programmes designed by government have the potential to solve poverty problems in Nigeria, (ii) determine whether the price of the program is affordable (iii) ascertain whether the marketing promotions adopted for the programme are effective (iv) evaluate the degree of accessibility of the programme to the poor masses (v) determine whether personnel used for the programme are right (vi) assess whether the process for obtaining poverty alleviation products are easy to understand and follow.

Sample

Quantitative survey research design methodology was adopted for this study. This is consistent with hypothesis testing and generalization of results [49]. The study was carried out in the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria and two states were randomly selected for the study in each zone as shown below:

North Central: Benue state, and Niger state

Northwest: Kano state, and Zamfara state

Northeast: Bauchi state, and Taraba state

Southeast: Enugu state, and Ebonyi state

Southwest: Ogun state, and Osun state

South-south: Bayelsa state, and Edo state

The unit of analysis in this study were the poor Nigerians who are the presupposed beneficiaries of poverty alleviations programmes designed by government. A sample size of 240 (20 from each of the six geo-political zones in Nigeria) were selected for the study. They were selected based on five characteristics of the poor which include: income range per day, educational level, access to basic amenities, type of occupation and where they reside.

Questionnaire design and administration

Structured questionnaire was the instrument used in collecting primary data. Marketing mix measurement scales were adapted from the literature [29,39,48]. However some items in the measurement scales were re-phrased to suit the local context of the respondents. The contents validity of the questionnaire was checked by ensuring that the measurement items were constructed in line with marketing theory and past measures adopted by similar studies. Face validity was also ensured using two well-experienced academic marketing researchers. The reliability of the instrument was checked using Cronbach’s alpha test which shows 0.84 coefficient relative 0.70 minimum benchmark suggested by Nunnally and Bernstein [50-55]. Based on this benchmark the instrument was deemed reliable.

The questionnaire was structured into two major sections: Section A captured the bio-data of the respondents while section B captured the marketing mix (major) constructs under investigation [56,57]. The questions were designed in five-point Likert-scales ranging from strongly disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (5 points). Copies of the questionnaire were administered in the six geo-political zones of Nigeria using research assistants well-trained for that purpose. Judgmental and convenience sampling techniques were applied in carefully choosing the respondents who were qualified to participate in the survey. Specifically, those below 18 years and individuals who earn above $1 a dollar were excluded from the study. Logit Regression Analysis was used to test the hypotheses [58].

Model Specification:

• Poverty Incidence in Nigeria (PIN) = f (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7)

• Where PIN = Poverty incidence in Nigeria

P1 = Poor poverty alleviation products (Poor PAProduct 1)

P2 = Poor poverty alleviation prices (Poor PAPrice 2)

P3 = Poor poverty alleviation promotion (Poor PAPromotion 3)

P4 = Poor poverty alleviation place (Poor PAPlace 4)

P5 = Poor poverty alleviation people (Poor PAPeople 5)

P6 = Poor poverty alleviation process (Poor PAProcess 6)

P7 = Poor poverty alleviation physical evidence (Poor PAPhysical Evidence 7)

• A Priori Expectation

P1< 0, P2 > 0, P3< 0, P4< 0, P5< 0, P6 < 0, P7 < 0.

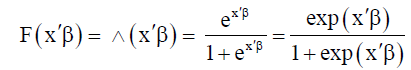

From the above model specification, Poverty Incidence in Nigeria is hypothetically a function of poor blending of the 7Ps of Marketing. Using a logit regression analysis model for this foregoing specified function, we have;

Where  is the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of

the logit regression model representing the predicted probabilities of

the model which lie between 0 and 1 (i.e. whether ‘poor’ or ‘not poor’

incidence). These are proxy for Poverty Incidence in Nigeria (PIN)

as the outcome (dependent) variable for poverty alleviation products

marketed through poor integrated marketing practices. The predictor

(independent) variables (x) are the 7Ps of marketing specified above,

each of which are ordinal. They take on the values of 1 to 5. Responses

with a score of 1 represent very weak marketing practice whilst those

with a score of 5 have very strong marketing practice. The 7Ps of

marketing were treated as categorical data.

is the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of

the logit regression model representing the predicted probabilities of

the model which lie between 0 and 1 (i.e. whether ‘poor’ or ‘not poor’

incidence). These are proxy for Poverty Incidence in Nigeria (PIN)

as the outcome (dependent) variable for poverty alleviation products

marketed through poor integrated marketing practices. The predictor

(independent) variables (x) are the 7Ps of marketing specified above,

each of which are ordinal. They take on the values of 1 to 5. Responses

with a score of 1 represent very weak marketing practice whilst those

with a score of 5 have very strong marketing practice. The 7Ps of

marketing were treated as categorical data.

Out of the 240 copies of questionnaire administered, 193 copies were returned. 47 others were not returned. This gives a percentage success response rate of 80.4%.

Table 3 shows that 107(55.4%) of the respondents captured in the survey are males while 86(44.6%) others are females. 54(28.0%) of them are < 30 years old; 78(40.4%) are 30 – 39 years old; 57(29.5%) are 40 – 49 years old; while 4(2.1%) others are ≥ 50 years old. In terms of their occupation, 87(45.1%) of them said they are unemployed while 32(16.6%) are self-employed; 41(21.2%) said they work with private organizations and lastly, 33(17.1%) others work with the government. The table also shows that 75.6% (16.6% + 26.4%+32.6%) of the respondents are poor (They earn less than one dollar (< N300) a day) while 24.4% are seemingly not. This means that the majority of the respondents captured are poor.

| Freq. | Percent | Freq. | Percent | ||||

| a. Gender | Male | 107 | 55.4% | c. Occupation | Unemployed | 87 | 45.1% |

| Female | 86 | 44.6% | Self Employed | 32 | 16.6% | ||

| Total | 193 | 100.0% | Private Employer | 41 | 21.2% | ||

| Civil Service | 33 | 17.1% | |||||

| b. Age | < 30yrs | 54 | 28.0% | Total | 193 | 100.0% | |

| 30 - 39yrs | 78 | 40.4% | |||||

| 40 - 49yrs | 57 | 29.5% | d. Income/per day | None | 32 | 16.6% | |

| ≥ 50yrs | 4 | 2.1% | < N100 | 51 | 26.4% | ||

| Total | 193 | 100.0% | N100 - N299 | 63 | 32.6% | ||

| ≥ N300 | 47 | 24.4% | |||||

| Total | 193 | 100.0% |

Table 3: Respondents’ Demographic Data.

Model summary

R-Square 0.821

Adj. R Square 0.793

S.E of the Estimate 0.35865

The results presented on Tables 4 and 5 above represent the output of the Multiple Linear Regression Analysis. The regression model is fit at R2 = 82.1%. The ANOVA result on Table 4 confirms that the explanatory variables (7Ps of marketing) altogether have a combined significant (F=12.563, p<0.05) effect on the poverty incidence in Nigeria. This is further confirmed in Table 5 through the slope coefficients of each explanatory variable and their corresponding p-values.

| Model | Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 11.311 | 7 | 1.616 | 12.563 | .000a |

| Residual | 23.668 | 184 | .129 | ||

| Total | 34.979 | 191 |

Table 4: ANOVA.

| Model 1 | Unstandardized Coeff. | Stdzd Coeff. | T | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | .707 | .104 | 6.807 | .000 | |

| Poor PAProduct 1 | .236 | .056 | .709 | 4.241 | .000 |

| Poor PAPrice 2 | .092 | .025 | .279 | 3.757 | .000 |

| Poor PAPromotion 3 | .110 | .043 | .332 | 2.538 | .012 |

| Poor PAPlace 4 | .061 | .023 | .169 | 2.601 | .010 |

| Poor PAPeople 5 | .034 | .021 | .104 | 1.644 | .002 |

| Poor PAProcess 6 | .039 | .038 | .116 | 1.019 | .010 |

| Poor PAPhysical Evidence 7 | .055 | .022 | .156 | 2.551 | .012 |

Table 5: Coefficients.

Thus, it can be inferred from these results that poor poverty alleviation products, pricing, promotion, distribution, people, process and poor physical evidence (p < 0.05) altogether account for high poverty incidence in Nigeria. This means that poor marketing programmes contributed to the failure of poverty alleviation programmes in Nigeria. Based on the results in Table 5, the seven null hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, and H7) which states that poor quality of poverty alleviation products, poor prices, poor promotion, poor place, poor people, poor process and poor physical evidence have no significant influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria will be rejected

To correct this past failure in poverty alleviation efforts, the following results on Table 6 reveal how poverty incidence in Nigeria can be reduced by effectively using integrated marketing mix model.

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAProduct | -3.797 | 1.018 | 13.902 | 1 | .000 | 44.571 |

| PAPrice | 1.236 | .330 | 14.054 | 1 | .000 | 3.442 |

| PAPromotion | -1.305 | .496 | 6.918 | 1 | .009 | .271 |

| PAPlace | -.605 | .230 | 6.914 | 1 | .009 | .546 |

| PAPeople | -.245 | .184 | 1.760 | 1 | .015 | .783 |

| PAProcess | -1.186 | .774 | 2.349 | 1 | .025 | .306 |

| PAPhysical_Evidence | .662 | .228 | 8.415 | 1 | .004 | .516 |

| Constant | .692 | 1.043 | .441 | 1 | .507 | 1.998 |

Table 6: Variables in the Equation.

On Table 6, the marginal effects of each slope coefficient in the logit model are presented together with their corresponding p-values and odd ratios.

• The sign of each slope coefficient obeys the a priori expectation rules;

• All the slope coefficients are significant – describing the marginal effect that;

• any 1% improvement in the quality of poverty alleviation products that reflect the needs of the masses will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 379.7% with an odd ratio of 44.51

• any 1% improvement in the prices (i.e. cost of accessing poverty alleviation products) will positively reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 123.6% with an odd ratio of 3.442

• any 1% improvement in poverty alleviation promotion will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 130.5% with an odd ratio of 0.271

• any 1% improvement in poverty alleviation distribution practices will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 60.5% with an odd ratio of .546

• any 1% improvement in the quality of poverty alleviation people will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 24.5% with an odd ratio of .783

• any 1% improvement in the poverty alleviation process will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 118.6% with an odd ratio of .306

• any 1% improvement in the physical evidence of poverty alleviation practices will reduce poverty incidence in Nigeria by 66.2% with an odd ratio of .516

Products

Findings from this study show that poor quality of poverty alleviation products has significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This means that poor products increases poverty situation in Nigeria. This is consistent with the Aliyu’s findings [31] who noted that products such as soft loans to investors, basic education for all, primary health care delivery systems, access roads, stable power supply, communication facilities, agriculture, small and medium scale industries designed to reduce poverty are not properly funded in Nigeria.. Findings from this study also show that improvements on the quality of products will make the highest contribution to poverty reduction in Nigeria relative to other marketing mix variables (see Table 6). This means that government should pay more attention to improvements in the quality of poverty alleviation products (e.g education, agriculture, power, roads, water, communications, markets, small and medium scale industries) relative to other marketing mix variables by properly funding them and making them available to the poor.

Prices

Poor prices of poverty alleviation products were found to have significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This means that prices of poverty alleviation products are not affordable by the poor masses and this increases poverty in Nigeria. This finding is supported by previous studies [36,37]. In Nigeria interests and collateral securities on loans, social infrastructure (water, electric, market, hospital, sanitation, business premises, education) bills, food prices and income taxes seem high and unaffordable by the poor. The implication is that prices at which these poverty alleviation products are sold should be improved by making them affordable to the poor.

Promotion

Findings from this study show that poor quality of marketing promotion of poverty alleviation products has significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This finding is supported by previous studies [37]. In Nigeria, it appears that the target audience (the poor) do not have proper information about the products, their prices, the places they can be found, the process to be followed in obtaining the products and the right individuals to meet. The implication is that government should embark on aggressive marketing campaign using the proper grass root channels of communications such as churches, mosques, town hall, clan, age grade and village meetings to inform and educate the poor about the products, their prices and places to obtain them.

Place

Poor place strategy was found to have a significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This means that poor distribution (place) strategy increases poverty syndrome in Nigeria. This finding is strongly supported by previous studies [40,41]. In most cases outlets for the distribution of poverty alleviation products such as banks, ministries, agencies are either not enough or found in rural areas where majority of poor masses reside. Government should improve on this by ensuring that the distribution outlets for poverty alleviation products are enough and located where poor masses can have access to them.

People

Findings from this study show that poor people has a significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This may mean that poor people are used in marketing poverty alleviation products and this increases poverty situation in Nigeria. This finding is supported by Aliyu’s [31] studies who noted that policy makers do not remember the poor in their economic and social policy decisions. He discovered that funds meant for developing and marketing of poverty alleviations products are embezzled or diverted due to corrupt leadership, poor management and bad governance. Government should therefore improve on the quality of people or officials employed for selling poverty alleviation products by ensuring that honest employees and good leaders who are sensitive to needs of poor are appointed and properly trained for service delivery.

Process

Poor process was found to have significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This means that the process adopted for marketing of poverty alleviation products was poor and this increases poverty situation in Nigeria. This is in line with Narang’s [45] study which show that ambiguous and complex service process produce customers’ dissatisfaction. In most cases the documentation processes for buying poverty products are complex and not easy to follow. The implication is that government should make the process for obtaining poverty alleviation products easy and as simple as possible.

Physical evidence

Findings from this study show that poor physical evidence has significant positive influence on poverty incidence in Nigeria. This may means that the physical facilities used in rendering services in places such as public schools, health centers, ministries and agencies are poor and this contributes to poverty incidence in Nigeria. Government should improve on physical evidence by proper funding of the program and provision of modern facilities in public schools, health centers, ministries and agencies. These modern facilities will help in proper implementation of poverty alleviation programs.

Poverty situation in Nigeria requires multi-faceted approach. The success of any intended goal of the government to alleviate poverty in Nigeria does not only depend on multi-domestic sectorial, financial and economic reform measures and strengthening of public institutions but also on significant improvements in the marketing approach to the problem. Specifically, there should be significant improvements on these marketing variables: poverty alleviation products, prices charged, marketing promotions, distribution, people, processes and physical evidence in order to reduce poverty menace in Nigeria.

Citation: Nwora NG (2019) Adopting Marketing Mix Model for Reducing Poverty Incidence in Nigeria. J Tourism Hospit 8:396. doi: 10.4172/2167-0269.1000396

Received: 13-Dec-2018 Accepted: 18-Feb-2019 Published: 25-Feb-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0269.19.8.396

Copyright: © 2019 Nwora NG. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.