Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2019)Volume 8, Issue 3

Background: Maternity waiting home (MWH) is a temporary residence where pregnant women who rarely access basic obstetric cares stay.

Objective: The study was aimed to assess women’s MWH satisfaction.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in three randomly selected districts of Jimma zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. A sample of 362 women who ever used MWH was recruited in the study. The sample size was proportionally allocated to each district. A simple random sampling was used. Data were collected using a pretested questionnaire-developed mainly based on MWH guideline. MWH standard of construction and utensils, services, social support and interpersonal communication (IPC) etc. were the major components of the tools. Data were analyzed using Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 statistical software. Reliability analysis was conducted for specific and overall satisfaction domains. Multiple linear regressions (β) were performed to identify predictors of satisfaction with MWH, p<0.05.

Result: A total of 362 mothers were participated in the study (response rate=98%). The overall mothers ’ satisfaction with MWH was 68.8%. Higher mothers’ satisfaction was from social support aspects: one to five women network (89.5%), cleaner/servant in MWH (88.9%) and husband (87.3%). And, lower satisfaction was from ambulance (24%), recreational (38.5%) and food (49.4%) services and utensils in MWH (56.2%). Nearly 2/5th users claim they do not come again and recommend MWH for others. Women’s overall satisfaction with MWH was

predicted by: length of stay in MWH (≤ 14 days), utensils in MWH, services (prenatal, food, sanitation, recreational), social supports (family, women’s 1-5 networks, and servants) and IPC with Health Care Workers (HCWs).

Conclusion: Women ’ s overall satisfaction with MWH was moderate (68.8%). However, most services (ambulance, recreational, food, sanitation) and MWH standard (construction and utensils) were lower extreme of satisfaction dimensions. Most services and length of stay in MWH predicted overall satisfaction; indicating MWH recommended services were also valuable for users. These low satisfaction and predictor variables will be barriers to women who never used and stopping return use. The health system should avail services recommended by the

guideline while strengthening social support, and shorter stay in MWH so that users advocate the innovation.

Mothers’ satisfaction; Maternity waiting home; Negative advocate; MCH strategy; Implementing MCH guidelines; Jimma- Ethiopia

FMOH: Federal Ministry of Health; HEWs: Health Extension Workers; HCWs: Health Care workers; HC: Health Center; IPC: Interpersonal Communication; MWH: Maternal Waiting Homes

Globally, maternal mortality rate (MMR) was fallen by nearly 44% over the past 25 years (i.e., from 385 to 216 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in time period 1990-2015). Specifically, Fifty-nine percent of world-wide maternal deaths occur in 10 countries; and Ethiopia being one of them. In 2015, about 11,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births were recorded in Ethiopia. In spite of the fact that health institution delivery behavior was increased in Ethiopia from 10% in 2011 to 26% in 2016, access to health facility continued to be a challenge for those who reside in rural areas. Therefore, home delivery is still common (for example one study reported about 73%) among women living in hard to reach areas [1-7]. This paved the way for the adaptation of strategies that specifically targeted reproductive age women living in disadvantaged settings focusing on promotion of safe delivery and reduction of maternal deaths.

The establishment of Maternity Waiting Home (MWH) is one of the strategies that focused on promotion of safe delivery. MWH is a residential facility where women who live remotely can wait before giving birth at health institution where obstetric care is available. Historically, the first MWH were intended for women with major obstetric abnormalities for whom operative delivery was anticipated but whose homes were in remote- inaccessible rural areas. Gradually, the concept has been enlarged to include "high risk" women i.e., women who live in settings poorly accessed with maternal health facilities and services. In Africa one of the early experiments with MWH (known as “Maternity Villages") was in Eastern Nigeria in the 1950s [8-13]. Historically, Attat was one of the oldest hospitals in Ethiopia to introduce the implementation of MWH on small scale in 1985. However, it is a recent phenomenon (2015) for Ethiopia to develop guideline on standardization of MWH services across the country. It was aimed to provide policy support for pregnant mothers who live in areas with difficult transportation, and suggested the women would come and stay in MWH 15 days before the due date of delivery so that they will get safe delivery service.

The guideline explicitly recommend access to a package of services related to ambulance, prenatal care, postnatal care, food, sanitation and recreation in every MWH found in health centers that were implementing the strategy. For example, according to the guideline, prenatal services include women’s health assessment, counseling and supports aimed to strengthen readiness for delivery, and health education about healthy maternity (nutrition, breast feeding, hygiene, etc.). On the other hand, postnatal services include mothers and newborn health assessment, provision of necessary care and vaccination and proper health education on healthy maternity and newborn care. And, recreation service indicated embrace availability of Television and other relaxation opportunities that serve for recreation and inherently educational. Furthermore, the guideline recommend consistent standard of construction of MWH (the appearance of the home should resemble the commonest type of a given family’ s residential house specific to settings) and utensils inside (chairs, sleeping arrangements like foam. mattress, sheet etc., cooking equipment including pots, spoon etc.) According to the sustainable development goals, by 2030, maternal mortality should be reduced to less than 70 (from 100,000 babies born alive) in Ethiopia whereas neonatal mortality rate should be reduced to less than 12 (from 1,000 babies born alive). The strategy was aimed to meet this outcome [8-13].

There were few studies conducted in other African countries on MWH utilization intention and practices and that can advise improvement of quality of MWH services. To mention some about reasons related to failure of utilization of MWH where it existed, results of studies performed in other regions of Ethiopia indicated that the absence of caretakers for children at home, home, husband and family did not allow women’s admission, shortage of transportation to and from the MWHs, families unable to bring the woman food items and unable to continuously supply food by traveling far distances, staying at MWH for a long period without delivering [14-19]. These reasons could be working for both ever and never used MWH. Furthermore, few studies [19-25] explored points on which mothers feel uncomfortable or comfortable during their stay in MWH. Accordingly, major categories of responses included: 1) Privacy (for example: dressing, overcrowded sleeping space), 2) Facilities in the rooms (for example: no bed or mattress, in adequacy of space for accompanies/relatives) and 3) Interpersonal relationship with health workers (for example: welcoming, reception on arrival, care, comfort and assurances provided by skilled birth attendants during the stay). Nonetheless, women’s reflections on level of satisfaction in relation to the quality of the packages as recommend by the working MWH guideline were not yet studied.

Although satisfaction is one of subtle concepts to define and understand, it is perceived to be helpful to make people keep use services and feel comforted. Satisfaction explains about people ’ s emotions based on their practical experiences evaluated against expectations and values. It is can be measured along extreme points on scales about objective of satisfaction, in this case MWH [9-14]. Therefore, in the context of the current study, mothers’ satisfaction with MWH was perceived as a multidimensional concept about emotional experiences of mothers: incorporating a wide range of familiarities related to services packages, interpersonal relationship, social supports and physical arrangements as recommended by MWH guideline. Perceived access to expectations will be elicited considering the guideline as it recommend access to food, essential utensils, presence of television for recreation and education, clean compound, social supports, professional maternal services accompanied with comfortable interpersonal relationship to provide comfortable, lovely and memorable life events [8,22-27]. Furthermore, studying user’s experiences and perspectives on MWH services will inform service providers, local planners, and decision makers to maintain the functionality of the strategy. Therefore, it is appropriate to study about women’s satisfaction over the course of their stay in MWH for their recent deliveries in Jimma zone.

Study design and setting

Community based cross sectional study design was employed to assess women’s level of satisfaction on MWH service in Jimma zone, Oromia regional state, South West Ethiopia. At the time of the study, Jimma zone had 21 districts. Ten of the districts had MWH in 50% of their respective health centers (HC). In this study, we included three (Manna, Kersa and Seka-Chokorsa) randomly selected of the ten districts-as expansion of MWH was based on the population of childbearing aged women in remote areas. Accordingly, Manna, Kersa and Seka-Chokorsa districts are found averagely about 20 kilometers away from Jimma town- the capital of Jimma zone towards West, East and South respectively. The study was conducted from March to April, 2018. In the year of study an estimated total population of the respective sites were 196,718 (Manna), 279,346 (Kersa) and 221,978 (Seka-Chokorsa) with respective pregnant women population of 6,826 (Manna) 9693 (Kersa) and 8302 (Seka-Chokorsa). A total of 13 health centers (HC) have functional MWH services across the districts (each 5 HC in Manna and Kersa districts and 3 HC in Seka-Chokorsa district). Similarly, there were 38 catchment villages in 13 HCs that encouraged pregnant women to utilize the MWHs.

Population and sample

In this study, women from Jimma zone districts having MWH, who ever used maternity waiting home from December 2016 to March 2018 were considered as target population. The sample population consisted of women randomly chosen from the 3 districts. Potential subjects were eliminated if they were critically ill or unable to respond to the questionnaire. At the time of data collection, the total target population across the selected districts was 538 women. A sampling frame of those women who ever used MWH between December 2016 and March 2018 was established separately for each of the three districts from MWH record book. Then, the sample size (N=369) was proportionally allocated to each district based on their respective number of MWH users. Then, the study participants were randomly selected by using computer generated random numbers from respective sampling frames. Finally, the selected women were approached at their home using addresses on the record book.

Sample size

Sample size required for the study was determined by using single population proportion formula: [n=[Zα/2]2*[p(1-p)/d2]. We considered the following parameters: proportion (p) of mothers ’ satisfaction during their stay in MWH=50% (p=0.05), level of significance (α=5%) to reject expected level of satisfaction, coefficient of reliability (Z) of standard deviation from expected level at 95% confidence level (Zα/2=1.96), tolerable margin of error (d=5%). Since our source population is less than 10,000 (N=538) correction formulas was used to calculate the final sample (n=224). By considering a 10% non-response rate, sample size became 246. Finally, design effect (D.E=1.5) was considered to determine the required sample size. Accordingly, the final sample size yielded was (NF=246*1.5=369).

Instrument and measurement

The instrument was developed after reviewing national guideline for MWH [8]. The questionnaire was first developed in English then translated into Afan Oromo and back translated to English to keep consistency. A pretested Afan Oromo version questionnaire was used for data collection. The instrument consisted of the three parts. Part I: Socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, marital status, educational status, occupation, religion, ethnicity and monthly income), Part II: Obstetrics and MWH history (e.g., parity, previous place of delivery, length of stay, person accompany, history of MWH). Part III: Overall satisfaction and satisfaction dimensions (e.g., standard of MWH, utensils in MWH, services (foods, prenatal, postnatal, sanitation, recreational), social support (husband, family, network, and janitor) and Interpersonal communication (IPC with HCWs, HEWs). Satisfaction was measured by using three points Likert scales ranging from not satisfied (1) to satisfied (3), the middle indicating indifference. Three points Likert scale was preferred as we noted pretest respondents were facing difficulty responding to the five points. Overall and specific satisfaction scores were calculated from the summation of their respective Likert scale items. Missing variables were excluded from the study. Then, the scores were converted to 100% for easy comparison among each other.

Data collection procedures

The data were collected through face to face interview led by five diploma nurses who fluently speak in Afan Oromo and had experience of data collection. The addresses of participants were obtained from the MWH records by the nurses who performed the interviews. The homes of the participants were visited by these nurses. Local guides assisted the nurses to the correct addresses. Finally, they conducted the interview in a confidential manner after securing oral informed consent. Two bachelor degree holder public health professionals supervised the data collection process. The data were cleaned and submitted to supervisors on daily basis. Consistency and completeness of the data were confirmed before approval by supervisors. Prior to data collection, pretest was done on 5% of the sample size in one of adjacent districts having MWH services. Based on the pretest finding, satisfaction dimension scales were modified to improve clarity of responses. Two days training was given for data collectors and supervisors on the purpose and procedures of the study. Thorough discussion was conducted on the tools during the training. Close supervision was done by principal investigators and supervisors throughout the data collection period. The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency of responses on daily bases. Data were first entered into Epi-data version 3.1 through double entry verification before exported to SPSS for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentages, mean, standard deviation, etc.) were computed and the results were presented by tables and figure. Pearson ’ s correlation coefficient was used to display correlation between overall and specific domains satisfaction. Reliability analysis was conducted for Likert scale questions and cronbach’s alpha (α ≥ 70%) were used to declare the scale items were internally consistent in the domain they belong. Scale items with inter-item correlation coefficient (r ≤ 10%) were removed from the domain to improve reliability of the scale. Then, satisfaction (overall and sub-dimensions) were constructed from items remained on the scale with α ≥ 70%. Accordingly, overall satisfaction was constructed from the summation of 12 questions asked in general terms on 3-point Likert scale. Specific domain satisfactions were the resultants of summations of series of questions about MWH standard, service packages, social support and IPC on 3-point Likert scale. Simple and multiple linear regression analysis were applied to model satisfaction on MWH. First, simple regression was executed to find independent variables at p-value less than 0.25. Then, candidate variables under the category of specific satisfaction domains, socio-demographic and obstetric history were inserted into multiple linear regression models for final adjustment. Then, all variables that remained in the model after using stepwise backward method at p-value less than 5% were accepted as significant predictors of satisfaction on MWH.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Three hundred sixty two respondents were involved in the study making a total response rate of 98%. The average (mean [x] ± standard deviation [St.D]) of respondents’ was (28.3 ± 3.6 years). More than half, 191(52.8%) of the respondents live in the age group of 25-29 years. Nearly all the respondents, 359 (99.2%) were married. Participants were predominantly, 327 (90.3%) Oromo ethnic group and 334 (92.3%) were Muslims. With regard to occupation, 234 (64.6%) of mothers were housewives. Two hundred and fifty two (69.6%) of mothers weren’t read or write, 109 (30.1%) were able to read or write. And, 187 (51.7%) husbands were able to read and write. More than half (58.0%) had average monthly income of ≤ 1000 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) at family level (Table 1).

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 362 | 100 |

| 20-24 | 41 | 11.3 |

| 25-29 | 191 | 52.8 |

| 30-34 | 108 | 29.8 |

| ≥35 | 22 | 6.1 |

| Mean (± St.D) of age (in year) | 28.3(mean) | (± 3.56) St.D |

| Residence | 362 | 100 |

| Rural | 361 | 99.7 |

| Town | 1 | 0.3 |

| Mothers’ educational status | 362 | 100 |

| Cannot read and write | 252 | 69.6 |

| Read and write | 109 | 30.1 |

| Others* | 1 | 0.3 |

| Husband educational status | 362 | 100 |

| Cannot read and write | 175 | 48.3 |

| Read and write | 187 | 51.7 |

| Mothers’ marital status | 362 | 100 |

| Married | 359 | 99.2 |

| Divorced | 3 | 0.8 |

| Mother’s occupational status | 362 | 100 |

| House wife | 234 | 64.6 |

| Farmers | 118 | 32.6 |

| Merchants | 9 | 2.5 |

| Government employee | 1 | 0.3 |

| Religion | 362 | 100 |

| Muslim | 343 | 94.3 |

| Orthodox | 19 | 5.7 |

| Ethnicity | 362 | 100 |

| Oromo | 327 | 90.3 |

| Dawuro | 15 | 4.2 |

| Kaffa | 12 | 3.3 |

| Amhara | 8 | 2.2 |

| Income | 362 | 100 |

| ≤ 1000 ETB | 211 | 58.3 |

| >1000 ETB | 151 | 41.7 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics MWH users, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia, April, 2018 (n=362).

Obstetric history, health facility access and MWH use of the respondents

The majority, 243 (67.1%) of respondents had 2-4 parity. Thirteen, 13 (3.8%) women had experience of giving their first birth at MWH, never elsewhere. Before their recent delivery at MWH majority, 234/349 (75.6%) of the multi-parity women had ever experienced delivering at home. Nearly two-fifth (38.4%) of the women stayed more than 15 days in MWH. Husbands and other family members were the major (>70%) companion of the women on their way to MWH. Though more than half, 200 (55.2%) of the women were taken to MWH on foot, slightly less than two-firth 134 (37%) accessed free vehicle including ambulance on their way to MWH. In fact, 184 (50.8%) of the respondents claimed living in areas where ambulance cannot reach. Additionally, 137 (33.8%) of the women should walk more than 1-2 hours to reach the MWH, and only 5 (1.4%) can reach there within 30 minutes. One hundred forty two (39.2%) women were ever diagnosed with risk of delivery complications. Regarding MWH rooms, 136 (37.6%) respondents claimed they shared a single room in three or more when they were expectant mothers. However, only 22 (6.1%) women claimed they shared a single room in three or more as postpartum mothers. More importantly, 142 (39.2%) women did not intend to come again to MWH for giving birth. And, 138 (38.1%) women who ever used MWH did not recommend it to other women (Table 2).

| Variables | Indicators | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | - | 362 | 100 |

| One | 13 | 3.6 | |

| Two to four | 243 | 67.1 | |

| Five and above | 106 | 29.3 | |

| History of MWH | - | 362 | 100 |

| Yes | 60 | 16.6 | |

| No | 302 | 83.4 | |

| Previous place of delivery (Before they gave birth in MWH) (n=349) |

- | 349 | 96.4 |

| Home | 234 | 75.6 | |

| Health institution | 115 | 24.4 | |

| Accompanies | - | 362 | 100 |

| Family | 273 | 75.4 | |

| Husband | 260 | 71.8 | |

| Neighbour | 44 | 12.2 | |

| Others* | 7 | 2 | |

| Length of stay in MWH | - | 362 | 100 |

| ≤ 14 days | 223 | 61.6 | |

| ≥ 15 days | 139 | 38.4 | |

| Mode of transportation | - | 362 | 100 |

| On foot | 200 | 55.2 | |

| Vehicle (free) | 134 | 37 | |

| Vehicle (paid) | 28 | 7.7 | |

| Estimated walking hours | - | 362 | |

| ≥ 2 hours (remote) | 15 | 4.1 | |

| 1-2 hours (far) | 122 | 33.7 | |

| 30 min-1 hour (moderate) | 220 | 60.8 | |

| <30 minutes (near) | 5 | 1.4 | |

| Area accessible for ambulance | - | 362 | 100 |

| Yes | 178 | 49.2 | |

| No | 184 | 50.8 | |

| Number of expectant mothers in a room | - | 362 | 100 |

| One | 67 | 18.5 | |

| Two | 159 | 43.9 | |

| ≥ 3 | 136 | 37.6 | |

| Number of postpartum mothers in a room | - | 362 | 100 |

| One | 175 | 48.3 | |

| Two | 165 | 45.6 | |

| ≥ 3 | 22 | 6.1 | |

| Use MWH again | - | 362 | 100 |

| Yes | 220 | 60.8 | |

| No | 142 | 39.2 | |

| Recommend MWH for others | - | 362 | 100 |

| Yes | 224 | 61.9 | |

| No | 138 | 38.1 |

Table 2: Obstetric and MWH use history, MWH users, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia, April, 2018 (n=362).

Satisfaction domains in the context of MWH: Reliability analysis

Before calculating magnitude of satisfaction on MWH, we executed reliability analysis based on major aspects the national guideline recommended. Overall satisfaction was considered as women ’ s summative experiences about MWH. Four specific satisfaction dimensions with respective sub-dimensions were: standard of MWH (construction and utensils), services (ambulance, recreation, food, sanitation, prenatal and postnatal), social support (husband, family/ relative, 1-5 women network, servant or cleaner), and interpersonal relationship-IPC (with health extension worker-HEWs and with health care workers-HCWs). Table 3 shows reliability tests for MWH satisfaction aspects (overall, domains and sub-domains. In this study, all satisfaction aspects (overall, domains and sub-domains) were found reliable at Cronbach’ s alpha of (ὰ ≥ 70%). For example, overall satisfaction scale for MWH was reliable at (ὰ=0.87). And, service (food=0.99, postnatal=0.90) and social support (servant/cleaner=0.98, women network=0.98 and husband=0.91) related satisfaction subscales were highly reliable (Table 3).

| MWH satisfaction dimensions | Cronbach’s alpha (ὰ score) |

|---|---|

| 1. Standard of MWH: guideline oriented physical arrangement of the home | |

| Construction of MWH | 0.74 |

| Utensils in MWH | 0.79 |

| 2. Services: guideline oriented maternal, food, hygiene and recreational services | |

| Ambulance service | 0.76 |

| Recreation service | 0.78 |

| Prenatal service | 0.82 |

| Sanitation food service | 0.85 |

| Postnatal service | 0.9 |

| Food service | 0.99 |

| 3. Social support: relevant sources of community supports* | |

| Family support | 0.86 |

| Husband support | 0.91 |

| 1 to 5 network support | 0.98 |

| Servant/cleaner support | 0.98 |

| 4. Interpersonal relationship (IPC)* | |

| With HEWs | 0.98 |

| With HCWs | 0.95 |

| 5. Overall satisfaction: general evaluation of MWH | 0.87 |

Table 3: Reliability test for overall and specific satisfaction dimension scales, MWH users, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia, April, 2018 (n=362).

Respondents’ satisfaction on MWH

Respondents’ satisfaction was constructed from the summation of items on reliable specific and overall satisfaction scales. MWH satisfaction domains were standard of the home, services, social support and IPC plus overall satisfaction. Then, the test scores for each specific aspects of satisfaction were converted to 100% for easy comparing (given the number of items on each scale vary).

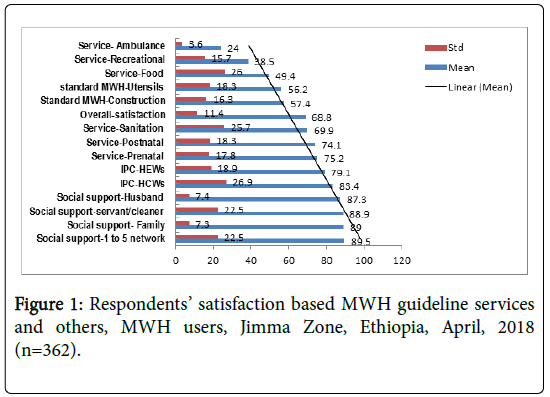

Figure 1 portrays the standardized mean scores of specific satisfaction aspects. Accordingly, the overall satisfaction on MWH was found to be 68.8%. Social supports accessed by women from (1 to 5 women network=89.5%, family/relatives=89%, servant/cleaner working in MWH=88.9% and husbands=87.3%) over the course of their stay in MWH were the highest satisfaction aspects.

Figure 1: Respondents’ satisfaction based MWH guideline services and others, MWH users, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia, April, 2018 (n=362).

The women were acceptably comfortable by interpersonal communication (IPC) with the HCWs (83.4%) and HEWs (79.1%) over the course of enrollment, stay and moving back home. Of the prominent service packages the guideline recommended for use and comfortable stay in MWH, women reported acceptable level of satisfaction with prenatal (75.2%), postnatal (74.1%) and sanitation (69.9%) services.

The standard of MWH as a home was felt to be less comfortable by the respondents in both its construction (57.4%) and equipment with essential utensils (56.2%). The respondents were reserved to provide responses towards favorable extreme along the scales used to measure satisfaction with food, recreation and ambulance services i.e., they were less satisfied with food (49.4%), recreation (38.5%) and ambulance (24%). Furthermore, the linear trend line showed recreation and ambulance services were the two most unacceptably low extreme of satisfaction (Figure 1).

Correlations of specific domains and overall satisfaction

In this study, overall satisfaction was considered an inclusive emotional evaluation of users about MWH. Multiple specific domains were expected to construct the overall satisfaction. This study looked on correlations within specific domains and between overall satisfactions. Accordingly, overall satisfaction was statistically significantly correlated with service (food, r=0.68, strong, pvalue< 0.05), social support (husbands, r=0.63, strong, p-value=0.01) and MWH standard (utensils, r=0.12, weak, p-value<0.05). This means satisfaction with food service and husband support were the two strong correlates of overall satisfaction with MWH. Nonetheless, food service was not significantly correlated with any other specific satisfaction domains. And, husbands support was significantly but weakly correlated with family support and prenatal services provided in MWH, not with the rest. Regarding correlations among the rest of the specific domains, only satisfaction with postnatal service was not significantly correlated with any other dimension of satisfaction. The rest had statistically significant correlations with at least one of the other aspects. One of the low extreme satisfaction domains, specifically Ambulance service was significantly correlated with satisfaction with prenatal services (r=0.13, weak, p-value=0.01) and IPC with the HEWs (r=0.13, weak, p-value <0.05) (Table 4).

Predictors of overall satisfaction with MWH

In this study, the specific satisfaction domains, obstetric history and socio-demographic predictors of overall satisfaction with MWH were assessed. Table 5 provides the final prediction status of candidate variables that significantly affected overall satisfaction at higher pvalue (<0.25) on simple linear regression model. These variables were inserted into multiple linear regression model for further adjustment at p-value <0.05. For example: overall satisfaction score averagely increased by 1.04 for every expectant mother who stayed shorter (<15) days in MWH compared to those who stayed longer. Likewise, those who intended to come to MWH again had an average excess satisfaction score of 3.63 compared to the non-intenders. Additionally, for every unit increase in satisfaction with food, recreation, sanitation, prenatal services and utensils in MWH, overall satisfaction score averagely increased by 11%, 18%, 20%, 25% and 20% respectively.

Similarly, for every unit increase in satisfaction with social supports (husband, other family member, servants/cleaners and women ’ s network) and IPC with HCWs, overall satisfaction increased by 20%, 10%, 19%, 8% and 4% respectively. However, MHW services (ambulance and postnatal) had no statistically significant effect on overall satisfaction with MWH. In the meanwhile, of the sociodemographic and obstetric history candidate variables (age, distance from the health facility, intention to come to MWH in future, recommendation of MWH to others and history of complication) only intention to come again was significantly predicted the overall satisfaction (Table 5). Therefore, predictors of satisfaction with MWH were summarized with the following final fitted model formula i.e., overall satisfaction on MWH=17.86+1.04 (shorter stay i.e., <15 days) +3.63 (intend to come again to MWH) +0.20 (utensils) +0.25 (prenatal service) +0.11 (food) +0.20 (sanitation) +0.18 (recreation) +0.04 (IPC/ HCWs) +0.20 (husband) +0.10 (other family) +0.19 (servant/cleaner) +0.08 (women network) +error. Generally, variables included in the above prediction formula, explained the variance of overall satisfaction with MWH by 90.8% (R2).

This study was aimed to assess satisfaction of women who ever used MWH. To conduct the assessment this study mainly used domains of MWH as specified on working guideline for Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia [8]. These include the standard of MWH itself and the services expected to be provided to every women available to MWH, Furthermore, the researchers decided to include other aspects based on evidence from various studies: the IPC [2-7,20-23] and social supports [9-13] along the continuum of health care service. In this study, overall satisfaction was considered- cumulative and embraces all elements relating to satisfaction with MWH. Therefore, it was expected to be constructed from women’s experiences of access to specific services, conditions and relationship compared to their expectations within a given limit of tolerance. Furthermore, the findings from this study were mainly discussed based on recommendations provided by the guideline.

Accordingly, this study has found out moderate amount of overall satisfaction score of 68.8%. In fact, women’s accesses to social supports from various sources (one to five women network, family, servant/ cleaner and husbands respectively) were the highest range (87.3%-89.5%) of satisfaction aspects over the course of stay in MWH. Furthermore, IPC with two categories of health professionals HCWs and HEWs were also higher (79.1%-83.4%) satisfaction points. According to MWH guideline the HEWs are community based health workers: they trace pregnant women and refer them to MWH when they near delivery by calling and availing ambulance services to the women [8]. They also organize social supports (women’s network, family/relative including husbands) to support the women on their way to MWH. And, the HCWs are clinicians including nurses and other experts who work in health center where MWH is available and they have to take care of pregnant women once they arrived to MWH. They are expected to provide MWH services to the women especially prenatal and postnatal ones. Many studies report client-provider relationship and communication as relevant elements of maternal satisfaction and service utilization [2-7,20-23].

In this study, three of six (sanitation, postnatal and prenatal) services that have to be provided to women when they were in MWH were supplied satisfactorily- slightly higher than the overall amount (69.9-75.2%). According to MWH guideline, once recruited in MWH, any women should get the following services: food, recreation, sanitation, prenatal and postnatal. Furthermore, the guideline extensively specifies about prenatal and postnatal services [8]. The prenatal services include assessment of health conditions, counseling and support to strengthen emotional and psychological readiness for delivery, and provision of health education about healthy maternity (nutrition, breast feeding, hygiene, etc.). And, postnatal services include assessment of health condition of the mother and newborn, providing necessary care and vaccination, and proper health education on healthy maternity and newborn care. Therefore, the higher satisfaction scores this study found on those services may be because mothers can have access to frequent visits by healthcare workers who give assurances and support across a few days of their stay in MWH.

On the contrary, the study has found out that the way the rest three (ambulance, recreation and food) services were supplied to the women seemed to be disappointing to users: satisfaction score ranging between 24 and 49.4 percent. The reasons for lower satisfaction on food and recreation may the challenge related to customization of food and recreation services as the women were not living in their own homes for the time being. For example, in MWH the women may not get the amount and type of foods and recreation they have been accustomed with while at home. Furthermore, ambulance service was the worst low satisfaction dimension concerning MWH topics. And, this may be the problem of access in general as few ambulances that are available for district health office are shared for a number of villages that can really tempt the coverage. In fact, the guideline specifies the women should get access to ambulance service at least on their way to MWH and when they back home if possible. Furthermore, women were less satisfied (56.2%-57.4%) with standard of construction of MWH and utensils inside. Many studies [9-12,16-19] in other Africa reported that food, transportation and utensils available in MWH were critical points of dissatisfaction and challenges to coming again for service.

In addition to assessing the magnitude of overall and specific satisfaction aspects, this study identified correlations between satisfaction aspects and predictors of overall satisfaction. Many satisfaction domains were statistically significantly correlated with each other expect that postnatal service was correlated with none. In fact, food service, husband support and utensils were the only aspects to correlate significantly with overall satisfaction. And, both high satisfaction aspects (e.g., social support from women’s network and family) and low satisfaction aspects (ambulance, recreation) were not correlated with overall one. This shows these aspects were less valuable for women and they were not things they bothered much about during their stay in MWH. Perhaps, food and utensils were fundamental requirements as they live there every day and husband is one of the most relevant sources of affection for women. The postnatal service was not correlated with any other aspects, may be because women were not bothering about what may happen post-delivery as they stay in MWH rather about delivery itself. The meaning and implication of satisfaction would be clearer when people’s experiences are interpreted based on expectations and elements valuable to them [9-14].

Regarding prediction, length of stay in MWH, intention to come gain to MWH for future, MWH services (prenatal, food, sanitation, recreation), MWH standard (utensils), IPC (HCWs) and social support (husband, other family, servant/cleaner and women network) were statistically significantly predicted overall satisfaction on MWH. Many studies [1-7,9-20,25] in few settings of Ethiopia and other African countries reported of long waiting, foods, IPC, sanitation and utensils to predict satisfaction and maternal service utilization. However, some relevant services recommended by the MWH guidelines were not mentioned among predictors of overall satisfaction with MWH tough they were correlated with overall satisfaction without adjustment. For example, ambulance service did not predict satisfaction when adjusted with other variables associated with satisfaction. This implies the women ’ s expectation for accessing ambulance was low compared other expectations they had concerning MWH. Likewise, postnatal service did not predict overall satisfaction when adjusted with other variables associated with satisfaction although it was associated with overall satisfaction itself at high pvalue (0.25) during simple linear regression analysis. This implies that the expectant mothers were not concerned about postpartum events when they were in MWH. In support of this idea, many studies reported mothers ’ low knowledge/misperceptions about postnatal complications in Ethiopia [8,13,14].

Therefore, this study has produced relevant findings that have implications for health system policy makers and implementers to think over urgently with regard to MWH strategy. For example, given that (foods, recreation, utensils and social supports and length of stay) were relevant for respondents and some of them were low satisfaction aspects, the mechanism of accessing foods, utensils and ambulances required for shorter length of stay and lovely services should be searched for in resource limited settings like Ethiopia. And, postnatal services were not the expectations and satisfaction element for child bearing aged mothers who should use MWH would be a reason for continuation of mortality. Finally, we would love to declare that this study was not without limitations. For example, as satisfaction is about the experience of women, qualitative data could have triangulated and improved the richness of the quantitative findings. For instance, challenges related to services especially (food, ambulance, and recreation) and availability of utensils inside the home could be explored further through observation, interviews and discussions. In connection to this, this study recommend further qualitative study to explore dimensions through which MWH services shall be reshaped and rendered to meet the aim of reducing maternal and newborn deaths and enhance service utilization. Furthermore, this study did not capture the networks and structures of all aspects of overall satisfaction at once.

Women’s overall satisfaction with MWH was moderate (68.8%). However, most services (ambulance, recreational, food, sanitation) and MWH standard (construction and utensils) were lower extreme of satisfaction dimensions. Most services (prenatal, sanitation, food and recreation), utensils in MWH, social supports, interpersonal communication with health care workers in MWH, intention to come again to MWH and length of stay in MWH predicted overall satisfaction; indicating most of the components recommended by MWH guidelines were also valuable for users as they go with mothers’ expectations. Given that intention to come again to MWH, food service and utensils were one of the predictors of overall satisfaction and significant portion of users did not intend to come again, felt food services and utensils in MWH were less than expected, the future of MWH strategy is a challenge.

These lower extreme satisfaction and predictor variables altogether will be barriers to women who never used MWH and stopping return use. Additionally, most of specific domains of satisfactions were correlated with each other. However, satisfaction with postnatal service was not correlated with other specific dimensions and did not predict overall satisfaction. This implies MWH user women were not thinking about postpartum challenges and there would be high chance of maternal and neonatal mortality to continue in resource limited setting if a perception of postpartum risks and expectations for services is not increased. The researchers recommend: 1) The health system should avail services recommended by the guideline while strengthening social support, technical (prenatal) services altogether with supportive interpersonal communication with health care workers and shorter stay so that pregnant women will use and advocate the innovation, 2) Qualitative study to further clarify mothers ’ perspectives and experiences to foster MWH strategy.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Jimma Univeristy, postgraduate and research coordinating committee ethically approved this study. The verbal consent was secured from every respondent after reading information sheet about the purpose, benefit and risk, right to withdraw and voluntary participation. The committee has approved the verbal consent as the study did not have any perceived risk on the participants.

Not applicable.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

We acknowledge Jimma University for funding this study. We are thankful to the study participants. Furthermore, we extend our gratitude to local guiders.

Jimma University financially supported this study. Jimma University had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript.

Yohannes Kebede, Fira Abamecha, Mamusha Aman and Abriham Tamirat conceived the idea. Yohannes Kebede, Fira Abamecha and Chali Endalew designed the study. Yohannes Kebede and Chali Endalew drafted the manuscript. All authors critical reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Citation: Kebede Y, Fira A, Endalew C, Aman M, Tamirat A (2019) User’s Satisfaction with Maternity Waiting Home Services in Jimma Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia: Implications for Maternal and Neonatal Health Improvement. J Women's Health Care 8:3. doi: 10.35248/2167-0420.19.8.464.

Received: 11-Mar-2019 Accepted: 10-May-2019 Published: 17-May-2019

Copyright: © 2019 Kebede Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.