Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0277

ISSN: 2167-0277

Research - (2019)Volume 8, Issue 4

This study aimed to compare the electromyographic (EMG) activity among participants with costo-diaphragmatic, mixed or upper costal breathing type. Forty male were classified according to their breathing type into three groups: costo-diaphragmatic, upper costal and mixed breathing type. EMG activity of diaphragm (DIA), external intercostal (EIC), sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and latissimus dorsi (LAT) muscles was recorded in the dorsal, left lateral and ventral decubitus positions, during the following tasks: 1) quiet breathing, 2) speaking, 3) swallowing, and 4) sustained maximal inspiration. DIA activity was higher in upper costal than in costo-diaphragmatic breathing in all tasks and body positions; was higher in mixed than in costo-diaphragmatic breathing in all tasks in the dorsal and ventral decubitus positions and only in task 4 in the left lateral decubitus position; was similar between upper costal and mixed breathing in all tasks and body positions. EIC activity was significantly higher in mixed than costodiaphragmatic breathing in all tasks in the dorsal decubitus position and only in task 4 in the left lateral decubitus position. SCM activity did not show significant differences. LAT activity was only higher in upper costal than costodiaphragmatic breathing in task 4 in the dorsal decubitus position, in tasks 1, 2 and 4 in the left lateral decubitus position, and in tasks 2, 3 and 4 in the ventral decubitus position. EMG activity of the DIA was the only muscle that allows to differentiate between upper costal or mixed breathing than costo-diaphragmatic in all tasks in the dorsal and ventral decubitus positions.

Electromyography; Respiratory mechanics; Muscles; Work of breathing; Posture

Normal respiratory mechanics depends on the interaction among the respiratory muscles, lung and rib cage compliance and the airflow in the airways to promote air going into and coming out of the lungs, making it available for gas exchange [1,2].

The main muscle involved in inspiration is the diaphragm, however the external intercostal muscles also participate in this function; and may receive support from the parasternal intercostal, sternocleidomastoid, scalene, upper trapezius, large dorsal and the pectoralis major muscles according to the demand imposed on the respiratory system [2-12]. Moreover, several authors have demonstrated that latissimus dorsi (LAT) muscle has an inspiratory action during increased inspiratory load in healthy subjects [4,13] and in patients with hyperpnea, emphysema, or asthma [14].

Breathing type has been defined depending on the expansion of the abdomino-thoracic region during inspiration at rest, and three types have been described [15,16]: 1) costo-diaphragmatic breathing; 2) upper costal breathing; 3) mixed breathing.

Electromyographic (EMG) activity of respiratory muscles between healthy subjects with upper costal and costo-diaphragmatic breathing type was compared in the standing position [17-19] and in the right lateral decubitus position [19,20]. Higher EMG activity of DIA muscle was observed in subjects with upper costal than costo-diaphragmatic breathing type in both body positions. These studies, however, did not include a group with mixed breathing type, neither was EMG activity recorded at dorsal, left lateral, and ventral decubitus positions.

EMG activity of DIA muscle was higher in healthy subjects with upper costal or mixed than in subjects with costo-diaphragmatic breathing type during tooth clenching at different decubitus positions, whereas EMG activity of EIC, SCM and LAT muscles was similar among breathing types [21]. However, the authors of this study did not record the EMG activity of these muscles in subjects at rest, speaking, swallowing and sustained maximal inspiration. A higher EMG activity of these muscles in subjects with upper costal or mixed breathing than in subjects with costo-diaphragmatic breathing at these tasks could suggest a greater muscular effort depending on the breathing type, since it is well known that there is a linear relationship between the electrical activity and the force developed by a muscle, and therefore, the muscular work [22-24].

Based on the aforementioned it would be expected to observe a higher EMG activity in the upper and mixed costal subjects than in subjects with costo-diaphragmatic breathing. Therefore, this study compares the EMG activity of the DIA, EIC, SCM and LAT muscles among subjects with costo-diaphragmatic, upper costal and mixed breathing type to achieve important knowledge about the activity of these muscles at different tasks and decubitus positions.

Participants

This cross-sectional study included 40 participants between 18 and 27 years old. Participants were students enrolled at the Dental or Medical school of the University of Chile volunteered for the study and signed an informed consent form after a detailed explanation of the experimental protocol and the possible risks involved. All procedures were made in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Chile, approved the study protocol (N° 0098/15).

Recruited participants were male in order to avoid difficulties with breast size, asymmetry of the breasts and the use of a bra by female subjects during EMG recording.

The selection criteria were participants with complete natural dentition (excluding the third molars), not current or history of orthodontic treatment in the last 12 months [25], not current or history of oro-facial pain, craniomandibular-cervical-spinal disorders, or maxillofacial and/or cervical trauma. All participants were healthy men, with full active university life and none of them had a medical diagnosis of breathing disorders. During clinical exam no participant presented respiratory difficulty like cold or environmental allergies, or was on medication that could have influenced muscle activity.

Determination of the breathing type

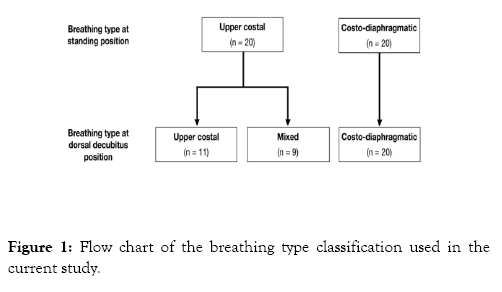

During the clinical exam, each participant was asked to remain in the habitual standing position with their feet 10 cm apart, to look straight ahead and to breathe normally for 2 min as a baseline. One calibrated examiner (R.C.) determined the breathing type according to previous works [17-21]. Briefly, the examiner gently placed the right hand on the upper chest and the left hand on the upper back. Next, they placed the right hand on the upper abdomen and the left hand on the lower right costal region. After checking for 10 inspirations on each step of the clinical examination, the subject was classified as upper costal breathing type if, during inspiration at rest, the superior thoracic expansion were predominant or as costodiaphragmatic breathing type if the abdominal and lateral costal expansion were predominant. Because the records were made at different decubitus positions in the current study, the breathing type was determined again in each participant at dorsal decubitus position. Each participant was asked to remain lying in the dorsal decubitus position. The same examiner classified clinically the breathing type as follows: First, the examiners gently placed the right hand on the upper chest. Next, they placed the right hand on the upper abdomen and the left hand on the lower right costal region. After checking 10 inspirations at rest, during each step of the clinical examination, each participant was assigned to one of the following groups: 1) costodiaphragmatic breathing type when the abdominal expansion was predominant (20 male participants who ranged in age from 18 to 27 years, with a mean age of 21.65 ± 2.81 years) 2); upper costal breathing type when superior thoracic expansion was predominant during inspiration at rest, (11 male participants who ranged in age from 18 to 24 years, with a mean age of 20.18 ± 1.66 years); 3) mixed breathing type when no clear predominance of superior thoracic expansion or abdominal expansion existed (9 male participants who ranged in age from 18 to 22 years, with a mean age of 19.67 ± 1.73 years). In the group of participants with the upper costal breathing type at standing position, 9 out of the 20 switched to the mixed breathing type in the dorsal decubitus position. In the group of participants with the costo-diaphragmatic breathing type at standing position, all 20 participants maintained the same breathing type in the dorsal decubitus position (Figure 1). The period during which the examiner selected the study sample was 12 weeks.

Figure 1: Flow chart of the breathing type classification used in the current study.

Electromyography

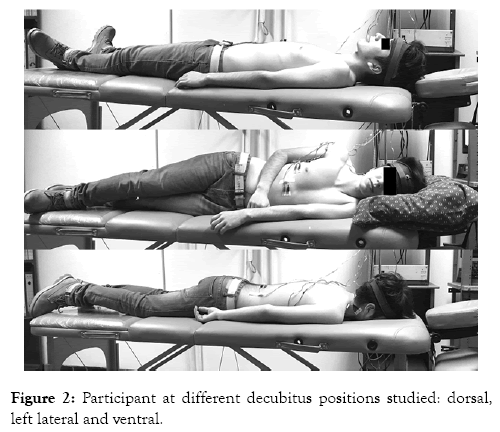

Bipolar surface electrodes (BioFLEX, BioResearch Associates, Inc., Brown Deer, WI, USA) were used for recording the EMG activity of the DIA, EIC, SCM and LAT muscles (Figure 2). Impedance was decreased by careful skin abrasion with alcohol. Electrodes were placed as follows [17-21,26]: on the DIA muscle, 1 cm below the xiphoid process; on the EIC muscle, between the 6th and 7th ribs on the imaginary vertical line that passes through the nipple; on the SCM muscle (middle portion), in the anterior border; and on the LAT muscle, in the projection of the 12th rib or lumbar vertebra L1 following the thoraco-lumbar fascia edge. The electrodes were located on the right side (except in the DIA muscle), because each participant was arbitrarily asked to lie on his left side. A large surface ground electrode (approximately 9 cm2) was attached to the forehead. The electrode impedance between both electrodes was measured (Kaise Electric Works, LTD., Model SK-200, Japan) being the maximal acceptable impedance 10 KΩ.

Figure 2: Participant at different decubitus positions studied: dorsal, left lateral and ventral.

EMG activity was recorded using a 4-channel computerized instrument in which the signals were amplified (Model 7P5B preamplifier, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA) and filtered (10 Hz high pass and 2 kHz low pass), with a common mode rejection ratio higher than 100 dB. The output was filtered again (notch frequency of 50 Hz), full-wave rectified and then integrated (time constant of 0.1 s) and recorded online in a computer exclusively dedicated to the acquisition and processing of EMG signals. The EMG signal was acquired at a sample rate of 200 Hz (50 Hz each channel) with a 12 bits A/D converter (MAX191) connected to the computer through an RS-232 port. The system was calibrated before each recording. EMG recordings were performed in the following body decubitus positions in a kinesiological bed (Figure 2):

- Dorsal decubitus: With the head supported by the bed.

- Left lateral decubitus: Head, neck and body horizontally aligned, checked by an external operator located approximately 3 m from the bed. The head and neck of each participant were supported by a Sleep Easy Pillow (Interwood Marketing Groups, Ontario, Canada).

- Ventral decubitus: With the face of participant resting on the contours of an oval space that allowed him to breathe naturally. Recordings were performed in one single session. The room light was turned off and the participant kept his eyes closed during the EMG recordings. Each participant underwent three EMG recordings while lying in a kinesiological bed, during the following tasks:

- Task 1: quiet breathing.

- Task 2: speaking the word “Mississippi”.

- Task 3: swallowing of saliva.

- Task 4: sustained maximal inspiration.

The decubitus positions as well as the task sequences were assigned by a random function program (Excel, Microsoft Corporation, USA). Before the EMG recording, an examiner explained the tasks to each participant so that he could perform them correctly. The instructions given for each task were the following: 1) to leave his jaw in resting posture; 2) to pronounce the word “Mississippi”. This phonetic method was chosen for being a functional activity commonly used by dentists in most oral reconstructive procedures [27]; 3) to perform the habitual swallowing of saliva. This task was chosen because it is a habitual physiological function [28]; and 4) to breathe in total lung capacity, holding the air for 10 s. This period was selected to ensure maximum and sustained muscle activity without producing a disorder in respiratory function.

Tasks 1, 2 and 3 lasted 10 s based on the duration of task 4. A 20 s resting period was allowed between each EMG recording in each task. To obtain the average value of the 10 s recording of each curve, measurements were obtained every 0.1 s using a computer program. Afterward, the average of the three EMG recordings of each task was used for the statistical comparisons. To check the homogeneity of the groups, age, body mass index (BMI) and waist/height ratio (WHR) were used.

Data analysis

Data of age, BMI, and WHR presented a non-normal distribution (p<0.05; Shapiro – Wilk test). Therefore, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare these variables among groups.

Ladder transformation was used to allow the normalization of EMG data. Comparison among breathing types were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey HSD posthoc test. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. The data were analyzed using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistic® v 21).

No significant differences were observed for age, BMI, and WHR among breathing types (p>0.05).

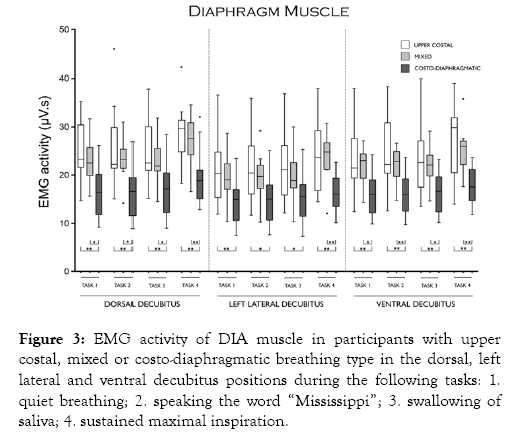

Figure 3 shows that DIA activity was higher in participants with upper costal than in participants with costo-diaphragmatic breathing in all tasks and body positions studied. DIA activity was higher in participants with mixed than in participants with costo-diaphragmatic breathing in all tasks in the dorsal and ventral decubitus positions, only in task 4 in the left lateral decubitus position. DIA activity was similar between participants with upper costal and participants with mixed breathing in all tasks and body positions studied.

Figure 3: EMG activity of DIA muscle in participants with upper costal, mixed or costo-diaphragmatic breathing type in the dorsal, left lateral and ventral decubitus positions during the following tasks: 1. quiet breathing; 2. speaking the word “Mississippi”; 3. swallowing of saliva; 4. sustained maximal inspiration.

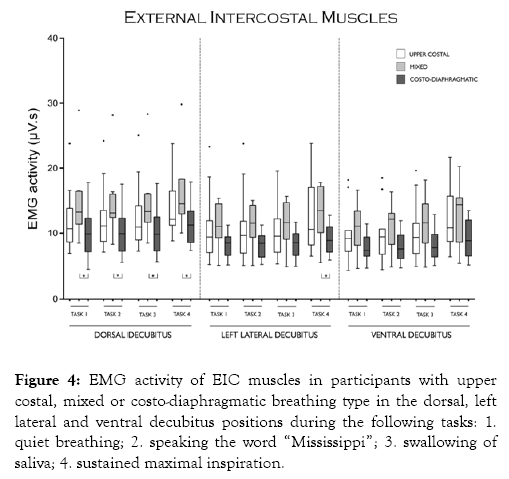

Figure 4 shows that EIC activity was significantly higher in participants with mixed than in participants with costodiaphragmatic breathing in all task in the dorsal decubitus position and only in task 4 in the left lateral decubitus position. EIC activity was similar between participants with upper costal and participants with mixed breathing in all tasks and body positions studied.

Figure 4: EMG activity of EIC muscles in participants with upper costal, mixed or costo-diaphragmatic breathing type in the dorsal, left lateral and ventral decubitus positions during the following tasks: 1. quiet breathing; 2. speaking the word “Mississippi”; 3. swallowing of saliva; 4. sustained maximal inspiration.

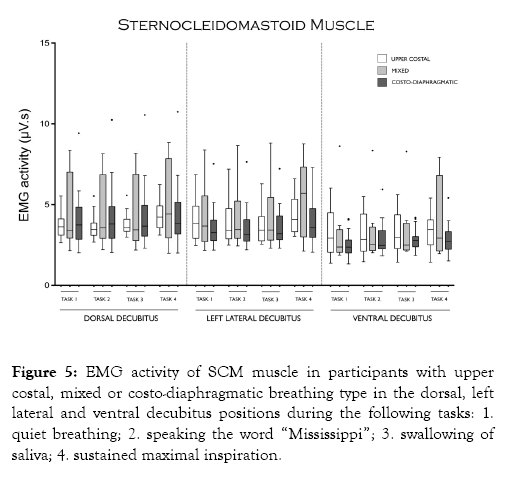

Figure 5 shows that SCM activity did not show any significant difference among breathing types during tasks and decubitus positions studied.

Figure 5: EMG activity of SCM muscle in participants with upper costal, mixed or costo-diaphragmatic breathing type in the dorsal, left lateral and ventral decubitus positions during the following tasks: 1. quiet breathing; 2. speaking the word “Mississippi”; 3. swallowing of saliva; 4. sustained maximal inspiration.

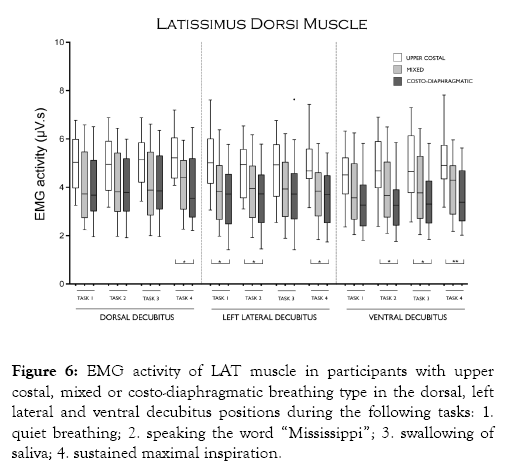

Figure 6 shows that LAT activity was only higher in participants with upper costal than in participants with costo-diaphragmatic breathing in task 4 in the dorsal decubitus position, in tasks 1, 2 and 4 in the left lateral decubitus position, and in tasks 2, 3 and 4 in the ventral decubitus position.

Figure 6: EMG activity of LAT muscle in participants with upper costal, mixed or costo-diaphragmatic breathing type in the dorsal, left lateral and ventral decubitus positions during the following tasks: 1. quiet breathing; 2. speaking the word “Mississippi”; 3. swallowing of saliva; 4. sustained maximal inspiration.

The higher EMG activity observed in participants with upper costal or mixed breathing than in participants with costodiaphragmatic breathing suggests a greater muscular effort depending on the breathing type as a compensatory mechanism to increase their ventilation due to their smaller lung capacity and less gas exchange, involving excessive upper chest wall activity [16,29,30]. This finding could support the necessity of physiotherapeutic program of breathing retraining in patients who do not present a costo-diaphragmatic breathing pattern.

The lower EMG activity observed in DIA muscle in participants with costo-diaphragmatic breathing when compared with upper costal or mixed breathing type is consistent with the evidence that this muscle improves pulmonary ventilation, mainly to the basal segments of the lung [31-34], being the main muscle of inspiration and responsible for generating the majority of inspiratory airflow [35]. This supports the concept that considers the costo-diaphragmatic as the optimal breathing type due to its efficiency in ventilation, increased gas exchange and oxygenation, with a lower breathing work [16,36,37]. This indicates that the breathing pattern reflects a principle of economy oriented toward minimal respiratory work [38].

EMG activity of EIC, SCM and LAT muscles recorded in the present study did no show a consistent significant difference among breathing types studied. This is in agreement with the finding observed in previous works between participants with upper costal and costo-diaphragmatic breathing in the standing and right decubitus positions [17-21].

Regarding the classification of the breathing type, the authors are aware that inductance plethysmography is an objective method to measure changes in thoracic and abdominal movements, but the clinical classification was preferred due to the clinical expertise of the examiner. Moreover, manual assessment of respiratory motion appears to be a valid and reliable clinical and research tool for assessing breathing movements, with good interexaminer reliability and greater ability to distinguish vertical rib cage motion than respiratory induction plethysmography [39].

It is important to note that in the present study nine of the twenty participants with upper costal breathing in the standing position changed to a mixed breathing in the dorsal decubitus position, so it would be interesting to conduct a future study to assess the mechanisms involved in the change of breathing type observed upon varying the body position.

The absence of SCM activity differences among the breathing types studied could be explained by the predominant effect of vestibular and/or visual afferents than other influences on its pool of motoneurons, due to its role as a postural rather than respiratory muscle [19].

In the present study, the participants were asked to perform all tasks voluntarily. This is important since it is well known that premotor drive from multiple descending pathways, i.e., from the motor cortex for voluntary respiratory tasks, is integrated at the spinal cord level [40,41]. They may arise directly from oligosynaptic pathways from the motor cortex to the diaphragm and intercostal motoneurons [42] or from local spinal reflexes. At the spinal level, all inputs acting on motoneurons and interneurons, including spinal reflexes, are coordinated to produce the appropriate motor output [41].

It is important to consider that afferences stemming from leg muscular proprioceptors, knee articular proprioceptors, and vestibular receptors may be involved in the EMG activity recorded upon varying the decubitus position of the participants [19]. Vestibular apparatus is the receptor detecting head position and change in space, therefore serving as one of the major organs of equilibrium [43], which could influence the motoneuron pools of respiratory muscles.

This study has at least three limitations. First, the subjects examined were only male, which limits the ability to extrapolate these findings to the general population; second, a small number of participants was included in the study; and third, surface electrodes on the chest could have captured electrocardiogram (ECG) and/or picked up activity from neighboring muscles.

From an overall point of view, results observed in the present study suggest that activity of DIA muscle recorded in the dorsal and ventral decubitus positions could be useful as instrumental diagnosis and follow-up of patients with upper or mixed breathing type under physiotherapeutic program of breathing retraining.

EMG activity of DIA muscle may be useful to differentiate between participants with costo-diaphragmatic breathing type and participants with upper costal or mixed breathing type in the dorsal and ventral decubitus positions.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Citation: Cordova R, Miralles R, Bull R, Gamboa NA, Santander H, Valenzuela S, et al. (2019) Respiratory EMG Activity between Subjects with Costo-diaphragmatic, Upper Costal or Mixed Breathing Type. J Sleep Disord Ther 8:306

Received: 18-Oct-2019 Accepted: 23-Nov-2019 Published: 30-Nov-2019 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0277.19.8.306

Copyright: 2019 Cordova R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited