Clinical Pediatrics: Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2572-0775

ISSN: 2572-0775

Research Article - (2023)Volume 8, Issue 3

Adolescent pregnancy is a serious and complex problem. An overwhelming majority of teens feel that avoiding teen pregnancy would be easier if they were able to have open discussions about contraceptives with their parents. Therefore, this study was done to assess parent-adolescent communication about contraceptives and identify factors associated with parent-adolescent communication in Bahir Dar city, North West Ethiopia. A school based cross-sectional study was conducted with a total of 821 adolescent. Multi stage sampling technique was used to recruit the students. The data was collected using a pretested and structured interviewer administered questionnaire. Then it was exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Bivariable and multi-variable logistic regression analysis were done.

Contraceptive; Adolescent; Parent; Communication

Adolescence is defined as the period between the ages of 10 and 19 during which a person transitions from childhood to adulthood [1]. During this time, adolescents frequently come into contact with high-risk circumstances, such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), unintended pregnancy and abortion [2]. Parents transmit to their children ideas, values, beliefs, expectations, knowledge, and information through parent-adolescent communication. Adolescents have been at risk to sex at an early age (<15 years) [3]. This early age at first sex among adolescents could expose them to the risks of unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. Since many adolescents begin sexual activity at a young age, communication between parents and adolescents about contraceptive is essential [4]. Talking with adolescents about contraceptives is a positive parenting practice [5].

Although there are several safe and effective contraceptives available, adolescent pregnancy is still on the increase [6]. Every year, approximately 21 million girls aged 15 to 19 years and 2 million girls age less than 15 years become pregnant in developing regions [7].

Adolescent pregnancies are highly likely to be unplanned. Almost half of the pregnancies among adolescents in Ethiopia are unintended, and 46% of those unintended pregnancies end in abortion [8]. The 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) showed that 25.1% of pregnancies among Ethiopian adolescents aged 15-19 years were unintended [9]. Lack of parental guidance and communication about sexual issues is a determinant of adolescent pregnancy [10]. An overwhelming majority of teens feel that avoiding teen pregnancy would be easier if they were able to have open discussions on contraceptives with their parents [11]. Adolescents had also suggested that parent-child communication about sexual issues may be an effective means of reducing teenage pregnancies [12].

However, contraceptives were one of the rarely discussed Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) topics [13-15]. Exiting studies in Ethiopia on parent adolescent communication on contraceptives communication are limited. Thus, this study was done to examine parent-adolescent communication about contraceptives in Bahir Dar city.

Study setting and design

A school based cross-sectional study was conducted in Bahir Dar City, Amhara region. Bahir Dar is the capital city of Amhara National Regional State.

Study population

The study participants were selected in school adolescents aged 10 to 19 years who were enrolled for the 2021-2022 academic year. This study does not include night program students, students who were seriously ill and absent from school at the time of data collection and married adolescents.

Sample size and sampling procedures

A total of 845 in school adolescents were included in the survey. The sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula with 5% margin of error, 95% confidence level; 50% of proportion of parent-adolescent communication, design effect of 2% and 10% non-response rate. Multi stage sampling technique was used to recruit adolescents. First, the schools were stratified as public and private. Taking 30% from each school, 7 public and 12 private schools were selected randomly.

Then, sample was allocated proportionally to each school. Two sampling frames were prepared; one for governmental schools and the other for private schools. Then, the required number of students was selected by generating a random number using excels from each sampling frame.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data was collected using a structured, interview administered questionnaire, which was adapted from previous literatures [16-18]. The questionnaire had five parts, socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge of adolescents about contraceptives, attitude of adolescents towards contraceptive communication, sexual behavior of adolescents, and communication of adolescents and parents about contraceptives. After guarantying respondent willingness to take part in the study, data collectors interviewed the students.

Data quality assurance

To assure the quality of the data, the questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated to Amharic and translated back to English. Pretest was done before the actual data collection to check the clarity, consistency, skipping pattern and order of the questions. Training was given to data collectors and supervisors for two days.

Data processing and analysis

Data were coded, entered, cleaned and exported to SPSS version 25 for analysis. Categorical variables were summarized using numbers and percentages and displayed by frequency tables and graphs, whereas continuous variables were presented by mean/median and standard deviations/IQR based on the distribution of the data. Binary logistic regression was run to see the association of each independent variable with parent adolescent communication about contraceptives.

Variables with P-value less than 0.25 in bivariable analysis were included to the multivariable logistic regression. An adjusted odds ratio at 95% confidence level was used to declare statistically significant association.

Socio-demographic characteristic of the respondents

Eight hundred twenty one (97.2%) adolescents participated in this study. Four hundred forty-three (54%) were females. The mean age of the adolescent was 14.5 (SD ± 2.6) years. Seven hundred fifty-three (91.7%) were Amhara in their Ethnicity. Six hundred eleven (74.4%) were from public school. Six hundred fifty-two (79.4%) were orthodox (Table 1).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 378 | 46 |

| Female | 443 | 54 | |

| Age | Oct-14 | 428 | 52.1 |

| 15-19 | 393 | 47.9 | |

| Educational status | Primary | 417 | 50.8 |

| Secondary | 404 | 49.2 | |

| Type of school | Private school | 210 | 25.6 |

| Public school | 611 | 74.4 | |

| Listen school mini media | No | 417 | 50.8 |

| Yes | 404 | 49.2 | |

| Ethnicity | Amhara | 753 | 91.7 |

| Others1 | 68 | 8.3 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 652 | 79.4 |

| Muslim | 81 | 9.9 | |

| Others2 | 88 | 10.7 | |

| Religious participation | Every day | 109 | 13.3 |

| At least once a week | 402 | 49 | |

| At least once a month | 239 | 29.1 | |

| Once a year | 71 | 8.6 | |

| Living arrangements of students | With Both parents | 696 | 84.8 |

| Others3 | 125 | 15.2 | |

| Mother's educational status; n=795 | Unable to read and write | 23 | 2.9 |

| Able to read and write (but no formal education) | 171 | 21.5 | |

| Primary (1-8th ) | 231 | 29.1 | |

| Secondary (9-10th) | 173 | 21.1 | |

| Diploma and above | 197 | 25.4 | |

| Father's educational status, n=775 | Unable to read and write | 17 | 2.2 |

| Able to read and write (but no formal education) | 109 | 15.4 | |

| Primary (1-8th) | 177 | 22.8 | |

| Secondary (9-10th) | 164 | 21.2 | |

| Diploma and above | 308 | 38.4 | |

| Occupation of the mother, n=795 | House maker | 387 | 48.7 |

| Employed (private) | 158 | 19.8 | |

| Employed (government) | 149 | 18.8 | |

| Others4 | 101 | 12.7 | |

| Occupation of your father, n=775 | Unemployed | 25 | 3.2 |

| Employed (private) | 319 | 41.2 | |

| Employed (government) | 235 | 30.3 | |

| Others5 | 242 | 25.3 | |

| Family size | <5 | 582 | 70.9 |

| ≥5 | 239 | 29.1 | |

| Family income per month | <4000 | 231 | 28.1 |

| 4001-7000 | 219 | 26.7 | |

| 7001-10000 | 246 | 30 | |

| >10001 | 125 | 15.2 |

Note: Others1: Tigrie, Gurage ,Agew, Oromo; Others2: Protestant ,Adventist; Others3: With Mother only, With Father only; Others4: Merchant, Daily laborer, Farmer Others5: Merchant, Daily laborer, Farmer.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of adolescents in Bahirdar city, North West, Ethiopia, June, 2022.

Knowledge of adolescent about contraceptives

In this study, five hundred sixteen (62.9%) adolescent had heard about contraceptives. When asked about method specific knowledge questions, from those who had heard about pills, 45(24.1%) were not sure or did not know whether oral pills should be taken daily, 47(17.7%) were not sure whether emergency pills must be taken within 72 hour after unprotected sex, 87(28.1%) were not sure or did not know whether injectable should be taken every 3 month. The analysis showed that 162(19.7%) adolescent had comprehensive knowledge about contraceptives (Table 2).

| Total knowledge indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| women should take a pill every day to avoid becoming pregnant (n=187) | Yes | 142 | 75.9 |

| No/Don’t know | 45 | 24.1 | |

| To prevent pregnancy emergency pills must be taken within 72 hour after unprotected sex (n=265) | Yes | 218 | 82.3 |

| No/Don’t know | 47 | 17.7 | |

| To prevent pregnancy injectable (Depo) should be taken every 3 months (n=310) | Yes | 223 | 71.9 |

| No/Don’t know | 87 | 28.1 | |

| Implants can prevent pregnancy up to 5 years (n=176) | Yes | 68 | 38.6 |

| No/Don’t know | 108 | 61.4 | |

| IUCD (loop) can prevent pregnancy up to 12 years (n=201) | Yes | 70 | 34.8 |

| No/Don’t know | 131 | 65.2 | |

| One condom can't be used more than once (n=449) | Yes | 226 | 50.3 |

| No/Don’t know | 223 | 49.7 | |

| Breast feeding can prevent pregnancy up to 6 months (n=119) | Yes | 81 | 68.1 |

| No/Don’t know | 38 | 31.9 | |

| Day 9-19 are unsafe period of the menstrual cycle (n=203) | Yes | 141 | 69.5 |

| No/Don’t know | 62 | 30.5 | |

Table 2: knowledge level of adolescent among who had awareness about contraceptives in Bahirdar city, North West Ethiopia, June 2022.

Three hundred sixty-four (44.35%) students believed that it is normal to have sexual feeling during adolescence. One hundred ninety-four (23.6%) had a boyfriend/girlfriend. One hundred fourteen (13.9%) adolescents had history of sexual intercourse.

The mean age for adolescents to have first sex was found 15.2 (± 1.3 SD). Among sexually active adolescents, forty-one (35.9%) had history of multiple sexual partner.

Parent-adolescent communication about contraceptives

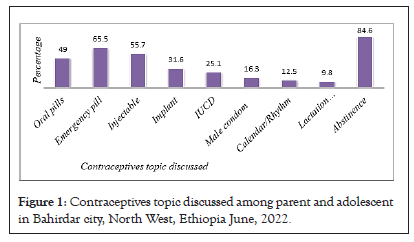

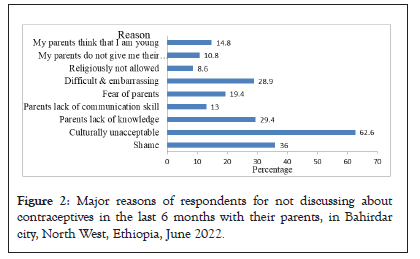

Although six hundred fifty-seven (80%) of the respondents reported that it was important to discuss about contraceptives with parents, one hundred eighty-three (22.3%) (95% CI:19%-25%) of adolescent had communicated with their parents. Among in-school adolescents who reported discussion with parents about contraceptives, the majority (84.6%) reported that they discussed about abstinence as shown in Figure 1. One hundred forty-five (79.2%) had discussed with their mothers, whereas 38(20.8%) discussed with their fathers. Nearly one-third of the adolescent preferred to discuss about contraceptives with their friends (peer), followed by their mothers (20.2%), brother/sisters (19.4%). Among three hundred five who didn’t discuss about contraceptives with parents, majority (62.6%) mentioned that parent adolescent communication about contraceptives is culturally unacceptable. Other mentioned feeling shame (36%), lack of knowledge (29.4%), feeling difficulty and embarrassing (28.9%) to talk as reasons for not communicating about contraceptives (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Contraceptives topic discussed among parent and adolescent in Bahirdar city, North West, Ethiopia June, 2022.

Figure 2: Major reasons of respondents for not discussing about contraceptives in the last 6 months with their parents, in Bahirdar city, North West, Ethiopia, June 2022.

Factors associated with parent-adolescent communications about contraceptives

In bivariable logistic regression analysis sex of adolescent, family size, age, income, school type, perceived importance of discussion, attitude, knowledge and history of sexual intercourse were candidate variable for multivariable logistic regression at P-value <0.25.

In the multivariable logistic regression model sex of adolescent, family size, age, knowledge, attitude, school type, and history of sexual intercourse were significantly associated with parent adolescent communication (Table 3).

| Variables | Category | Parent adolescent communication | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | Male | 47 | 331 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 136 | 307 | 3.120 (2.163,4.50) | 2.675 (1.761,4.065)** | |

| Age | Oct-14 | 52 | 376 | 1 | 1 |

| 15-19 | 131 | 262 | 3.615 (2.528,5.171) | 1.641 (1.042,2.586)* | |

| Family size | <5 | 89 | 493 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥5 | 94 | 145 | 3.591(2.546,5.065) | 2.764 (1.791,4.267)** | |

| Family income per month | <4000 | - | 194 | 1 | 1 |

| 4001-7000 | 38 | 181 | 1.101 (.670-1.808) | .780 (.438,1.389) | |

| 7001-10000 | 60 | 186 | 1.691 (1.072-2.670) | .926 (.514,1.667) | |

| >10001 | 48 | 77 | 3.269 (1.975-5.408) | 1.617 (.764,3.425) | |

| Knowledge | Not Knowledgeable | 104 | 555 | 1 | 1 |

| knowledgeable | 79 | 83 | 5.079 (3.5,7.372) | 1.661(1.016,2.717)* | |

| Attitude | Unfavorable | 83 | 535 | 1 | 1 |

| Favorable | 100 | 103 | 6.258 (4.369,8.965) | 4.014(2.618,6.155)** | |

| Perceived importance of discussion | No | 16 | 132 | 1 | - |

| Yes | 167 | 506 | 1.819 (1.127,2.934) | 1.495(.8,2.793) | |

| Ever had sex | No | 130 | 577 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 53 | 61 | 3.856(2.548,5.836) | 2.236(1.341,3.731)* | |

| Types of school | Public | 155 | 456 | 1 | |

| Private | 28 | 182 | .453 (.292,.701) | .451(.245,.831)* | |

Note: COR: Crude Odd Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odd Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval *=p value <0.05 and **=p value ≤0.001.

Table 3: Bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression of parent adolescent contraceptives communication in Bahirdar city, North West Ethiopia, June, 2022.

This study revealed that parent adolescent communication about contraceptives was 22.3% (95% CI: 19%-25%). This finding is in line with studies done in Weldia (20.9%), and Awabel (21.2%) [19,20]. The possible reason may be similarity in the measurement of outcome variable. However the proportion of school adolescents who reported parent adolescent communication about contraceptives was lower than studies done in Wereta (43.3%) and Yirgalem (36.1%), the difference may be due to the difference in the study population [21,22]. The study done in Yirgalem and Wereta collected information from late adolescent (from grade 9-12 students) who may better communicate contraceptives than early adolescent, which may increase the proportion of adolescents who communicated with parents about contraceptives. The finding in this study was lower than studies conducted in China (35%), Nigeria (50.2%) and Gambia (42.2%) [23-26]. The possible explanation for this discrepancy may be due socioeconomic differences and culture related to openness of contraceptives discussion. Contraceptive conversations are deemed a taboo subject in Ethiopia. The other reason for this difference might be difference related to parenting style.

However, the proportion of in-school adolescents who reported communication with parents about contraceptives in this study was higher than studies conducted in Nepal (10.1%), (2.8%) (5,27), Bangladesh (4.4%) and Myanmar (5.3%) [27-29].

This difference might be due to tool differences. In this study contraceptives include all pregnancy prevention method like condom, abstinence and others whereas in that study condom and abstainance were not included.

Adolescents who had favorable attitude towards parent adolescent communication about contraceptives had higher odds of discussing about contraceptives with their parents compared to adolescents who have unfavorable attitude. This is in line with study done in Bodity town, Southern Ethiopia. Similarly adolescents who were knowledgeable about contraceptives had higher odds of discussing about contraceptives with parents compared to adolescents who have poor knowledge. This is due to adolescents who had knowledge about contraceptives was eager to communicate the issue with parents. This in line with study done in Debre Markos [30].

The odds of parent-adolescent communication were higher among female adolescent than male adolescent. This is in line with study in Myanmar in Ambo, Ethiopia and the Netherlands [31]. The reason for this might be the fact that those females spend more time in the home where they can easily access their parents. In addition it might be due to adolescent girls are more vulnerable; thereby, they require more information on contraceptives to lead a healthy life.

Adolescents aged 15-19 years had higher odds to communicate with parents about contraceptives than adolescent who were in the aged 10-14 years. This is in line with study done in Nigeria. The implication is that the discussion about contraceptives varies as adolescents approach the late adolescence stage.

Adolescent who were sexually active were 2.2 times more likely to communicate with their parents about contraceptives than adolescent who were not sexually active. This is in line with study done in Weldia and in Amhara region [32]. This might be due to the fact that these adolescents might have higher perceived risk of pregnancy.

The other possible reason might be due to fear of complication that comes after sexual intercourse; sexually active adolescent may discuss this issue with their parent. Similarly the odds of parent-adolescent communication about contraceptives among students who were from large family (family size ≥ 5) were 2.7 times higher compared to students from households with small family size. This was supported by a study done in Dera woreda, North West Ethiopia [33]. The possible reason might be as family member increase they can easily predict the outcome of poor communication between family members. In addition there might have different information source as family member increase, the information they got from different source may pave the way for initiation of communication.

Communication about contraceptives between adolescent and their parent was low. Favourable attitude toward parent adolescent communication, being sexually active, female sex, age 15 to 19, knowledgeable toward contraceptives, and family size of ≥ 5 were significantly associated with parent adolescent communication about contraceptives. Therefore parent shall give especial emphasis for male adolescents. It is important to encourage and empower parents to start to communicate with their adolescent while the adolescents are still in early adolescent years, before they become sexually active. The health extension workers and other health professionals shall teach parents how to communication their adolescent and facilitate the community to encourage open discussion about contraceptives among family members with their adolescents.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Wubet B, Worku G, Abeje G (2023) Parent-Adolescent Communication about Contraceptives and Associated Factors in Bahir Dar City, North West, Ethiopia. Clin Pediatr. 8:237.

Received: 10-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. CPOA-23-21448; Editor assigned: 12-Apr-2023, Pre QC No. CPOA-23-21448 (PQ); Reviewed: 26-Apr-2023, QC No. CPOA-23-21448; Revised: 04-May-2023, Manuscript No. CPOA-23-21448 (R); Published: 12-May-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2572-0775.23.8.237

Copyright: © 2023 Wubet B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.