Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2022)Volume 11, Issue 6

Background: Birth preparedness and complication readiness are important factors in the reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality as well as infant morbidity and mortality. Objective: This study was intended to assess the level of knowledge and practice to birth preparedness, and complication readiness (BPCR) among pregnant women visiting Debreberhan town governmental health institutions. Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Debreberhan Town Health Institutions from January 1 to 30, 2019. The sample size was 340 pregnant women, and one referral hospital and three health centers located in the town were included in the study. A systematic random sampling method was utilized. A structured questionnaire was utilized. The data were entered into EPI data manager version 3.3 and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 23. The statistical association was performed by chi-square test for categorical variables. Multivariate analyses were performed. Results: All of the study subjects were successfully interviewed (340), yielding a response rate of 100%. Of the study subjects, 5 (1.5%) did not mention any danger signs during childbirth or labor. One hundred seventy-one (50.3%) of the respondents mentioned three or more danger signs. Among the study participants, 191 (56.2%) were prepared for birth and its complications. Maternal education was a strong predictor in preparation for birth and complications. Illiterate mothers were approximately five times less likely to be prepared for birth and complications than literate women (AOR= 5.013 (1.236, 20.329)). Conclusion: The status of birth preparedness and complication readiness was low in our setting. Maternal literacy, knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth, history of stillbirth, family size, monthly income, age, and advice given to partners on birth preparedness during ANC follow-up were found to be strong determinants of birth preparedness and complication readiness. Health professionals working in Debre Berhan town public health institutions should provide adequate health education and promotion activities to enhance the awareness of pregnant mothers regarding the importance of birth preparedness and complication readiness. A nationwide, prospective, community-based study should be conducted to investigate the actual readiness for birth and complications.

Birth preparedness, Complication readiness, Maternal health

The World Health Organization (WHO) indicated that more than half a million women die each year from complications of pregnancy and childbirth, with the vast majority of these deaths (99%) occurring in the developing world. Across all developing countries for every 100,000 live births, 450 women died during pregnancy, childbirth, or the postpartum period [1].

Maternal mortality is a substantial burden in developing countries. Improving maternal mortality has received recognition at the global level, as evidenced by the inclusion of reducing maternal mortality in the Millennium Development Goals. Since it is not possible to predict which women will experience life-threatening obstetric complications that lead to maternal mortality, receiving care from a skilled provider (doctor, nurse, or midwife) during childbirth has been identified as the single most important intervention in safe motherhood [2].

The 2016 EDHS pregnancy-related mortality ratio (PRMR) for Ethiopia is 412 deaths per 100,000 live births for the seven years before the survey. The confidence interval for the 2016 PRMR ranges from 273 to 551 deaths per 100,000 live births. More than 6 in 10 women (62%) aged 15-49 receive antenatal care (ANC) from a skilled provider (doctor, nurse, midwife, health officer, and health extension worker). Only 26% of births occur in a health facility, primarily in public sector facilities. However, 73% of births occur at home. Women with more than secondary education and those in the wealthiest households are more likely to deliver at a health facility. Only 5% of births in 2000 were delivered in a health facility, compared to 26% in 2016. Overall, 28% of births are assisted by a skilled provider, the majority by nurses/ midwives. Most births are delivered by unskilled traditional birth attendants (42%). Women in urban areas (80%), those with more than secondary education (93%), and those living in the wealthiest households (70%) are most likely to receive delivery assistance from a skilled provider. Skilled assistance during delivery has increased from 6% in 2000 to 28% in 2016 [3].

Birth preparedness and complication readiness are important factors in the reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality as well as infant morbidity and mortality. Therefore, there is a need to assess the knowledge, practice, and factors influencing birth preparedness and complication readiness [4].

Key danger signs during pregnancy include severe vaginal bleeding, swollen faces or hands, and blurred vision. During childbirth, severe vaginal bleeding, prolonged labor (>12hrs), convulsions, and retained placenta are observed [1].

BP/CR encourages women, households, and communities to make birth arrangements such as identifying or establishing available transport, setting aside money to pay for service fees and transport, and identifying a blood donor to facilitate swift decision-making and reduce delays in reaching care once a problem arises. To have birth preparedness and complication readiness at the provider level, nurses, midwives, and doctors must have the knowledge and skills necessary to treat or stabilize and refer women with complications, and they must employ sound normal birth practices that reduce the likelihood of preventable complications. Facilities must have the necessary staff, supplies, equipment, and infrastructure to serve clients with normal births and complications, and they must be open, clean, and inviting [1]. Every pregnancy faces risks somewhere in the world and a woman dies as a result of complications arising during pregnancy and childbirth. The majority of these deaths are avoidable by accessing the quality of maternal health services [5].

Skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth are important intervention in reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pregnant mothers who receive ANC from a skilled provider are informed about danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth, advised on birth preparedness and complication readiness, and get blood tests for infection screening and anemia, a urine test, tetanus toxoid injections, iron and folate supplements, deworming medications and a thorough physical examination done to identify any problems [6].

This study was conducted to assess the current knowledge of how pregnant women prepare for birth and the eventuality of an emergency. Therefore, this study aims to fill the gap by assessing the current level of BP/CR with determinant factors among pregnant women who visited Debre Berhan Town Governmental Health Institutions, North East, Ethiopia. The findings from this study might provide valuable information about the knowledge, practices, and factors that influence BP/CR among pregnant women and this might help us obtain baseline data for future studies and might be helpful for the relevant stakeholders in the planning and implementation of intervention activities to prevent, delay and improve maternal and neonatal survival [7].

The objective of this study was to assess knowledge and practices towards birth preparedness and complication readiness as well as factors associated with their practices among pregnant women attending ANC follow-up in Debre Berhan Town Governmental Health Institutions from January 1 to 30, 2019.

Study Area and Period

This study was conducted in Debre Berhan Town Governmental Health Institutions, which are located in the North Shewa Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia; located 130 km in the northeast of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The town has one referral hospital and three health centers. In 2018, approximately 10,997 pregnant mothers visited antenatal care clinics; of these 5,451, were pregnant in Debreberhan town health centers, and 5,546 pregnant mothers visited Debreberhan Referral Hospital (DBRH). The study was conducted from January 1 to 30, 2019.

Study Design

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted among pregnant women in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions.

Source Population

All pregnant women who underwent ANC follow-up in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions.

Study Population

All pregnant women who had ANC follow-up in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions during the data collection period.

Inclusion Criteria

• All pregnant women who had ANC follow-up in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions during the data collection period.

Exclusion Criteria

• Those pregnant women who were not mentally and physically capable of being interviewed

• Those pregnant women were not willing to give information

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

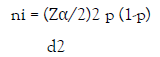

The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula considering a study conducted in Addis Ababa Public Hospitals. The prevalence of birth preparedness and complication readiness in that study was 72%. The minimum sample size required for this study was determined by using a single population proportion formula.

where: ni= minimum sample size required for the study

Z= standard normal distribution (Z=1.96), CI of 95% = 0.05

P= prevalence of bone fracture among Victims of road traffic accidents is unknown in my study area; hence, p= 72% (0.72) was used

d=Absolute precision or tolerable margin of error= 5% (0.05)

ni = (1.96)2 ×0.72 (1-0.72) = 310 (0.05)2

Consider 10% for non-respondents = 31

The final sample size was = 341

Dependent Variables

• Birth preparedness and complication readiness

Independent Variables

• Socioeconomic and demographic factors (age, marital status, religion, ethnicity, education, income, family size).

• Obstetric factors (parity, complications experienced, history of stillbirth).

• ANC follow-up

• Husband’s factors (age, occupation, education, income)

• Knowledge of key danger signs of pregnancy, labor/childbirth

Operational Definitions

Knowledge of obstetric complication(s): Symptom of obstetric complication(s) reported by a woman who may occur in women during pregnancy, delivery, or within 6 weeks after delivery.

Practice: Woman’s usual activities or behaviors about normal and complications of pregnancy, labor/childbirth

Knowledgeable of key danger signs of pregnancy: A woman is considered knowledgeable if she can mention at least two of the three key danger signs for pregnancy (vaginal bleeding, swollen hands/face, and blurred vision) spontaneously or after prompting.

Knowledgeable on key danger signs of labor/childbirth: A woman is considered knowledgeable if she can mention at least three of the four key danger signs for labor/childbirth (severe vaginal bleeding, prolonged labor(>12 hours), convulsions, and retained placenta) spontaneously or after prompting.

Birth preparedness: A woman is considered birth prepared if she identified the place of delivery, saved money, and identified a mode of transport ahead of childbirth.

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

A structured questionnaire mainly adapted from JHPIEGO monitoring BP/CR (1) was developed in English in such a way that it includes all the relevant variables to meet the objectives. The English version was translated to Amharic for better understanding, and then the Amharic version was translated back to English to check for its original meaning. The questionnaire consisted of sociodemographic information of the respondents, questions related to knowledge/awareness of respondents on danger signs during pregnancy, questions related to knowledge/awareness of respondents on BPCR, personal experience of respondents related to last pregnancy, and so on.

Five BSc health professionals were assigned to collect the data from the questionnaire, and two BSc/ MSc health professionals supervised the data collectors in the process of data collection. To maintain data quality, training was given to data collectors and supervisors for 3 days. Properly designed data collection materials were developed. Supervision was carried out daily to check completeness, and consistency by both the supervisors and the principal investigators to maintain the quality of the data. The pretest was performed on 10% of participants to the actual data collection time, and a correction was carried out.

Data Analysis

After data collection, each questionnaire was given a unique code. The principal investigators prepared the template and entered data using EPI data and then translated them into SPSS version 23 statistical software for analysis. Five percent of the data were rechecked. Frequencies were used to check for missed values and outliers. Any error was corrected after the revision of the original data using the code numbers.

Frequencies and proportions were used to describe the study population about sociodemographic and other relevant variables (age, marital status, gravidity, parity). The statistical association was performed by chi-square test for categorical variables. The strength of association between independent and dependent variables was assessed using crude odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Multivariate analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Department Research Ethics Review Committee of Debre Berhan University. This letter of ethical clearance as well as a letter of cooperation was sent to the hospital manager/medical directors. Data collection was started after permissions were obtained. Data that were collected from the participants were kept secure to maintain confidentiality. Voluntary participation was ensured, and participants were free to opt-out.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

A total of 340 study pregnant women were successfully involved in the study, yielding a response rate of 100%. Approximately 55.3% of the mothers were aged 25-34 years. The mean age was 31 years (SD=5.221). Nearly two-thirds (74.1%) were Orthodox Christian. Approximately (15.9%) of the mothers were illiterate. The majority (85.3%) were married. The average monthly income for the majority of the mothers (90.6%) was > 1000 ETB (Table 1).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 15-24 | 42 (12.4) |

| 25-34 | 188 (55.3) |

| >=35 | 110 (32.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 10 (2.9) |

| Married | 290 (85.3) |

| Widowed | 22 (6.5) |

| Divorced | 18 (5.3) |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox | 252 (74.1) |

| Catholic | 3 (0.9) |

| Muslim | 81 (23.8) |

| Protestant | 4 (1.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Amhara | 255 (75) |

| Oromo | 83 (24.4) |

| Others | 2 (0.6) |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 117 (34.4) |

| Farmer | 13 (3.8) |

| Daily laborer | 9 (2.6) |

| Gov’t employees | 165 (48.5) |

| Private employees | 9 (2.6) |

| Private business | 27 (7.9) |

| Educational status | |

| Illiterate | 54 (15.9) |

| Read write | 16 (4.7) |

| Grade 1to 8 | 66 (19.4) |

| Grade 9 to 12 | 46 (13.5) |

| Certificate & above | 158 (46.5) |

| Family size | |

| 1-3 | 223 (65.6) |

| 4-6 | 108 (31.8) |

| >=7 | 9 (2.6) |

| Monthly income in EBR | |

| <3297 | 392 (61.9) |

| > or = 3297 | 241 (38.1) |

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant mothers who visited Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Husbands (for women married and in the union)

Out of 340 pregnant women, (85.3%) were married and in the union. The majority of the husbands (50.3%) were between the age group of 25-34 years. Most of them were involved in private business and their educational statuses were certificates and above, 42.4% and 35.2% respectively (Table 2).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 15-24 | 4 (1.4) |

| 25-34 | 146 (50.3) |

| >=35 | 140 (48.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Farmer | 28 (9.6) |

| Governmental employees | 96 (33.1) |

| Private employees | 24 (8.3) |

| Private business | 123 (42.4) |

| Daily laborer | 19 (6.6) |

| Educational status | |

| Illiterate | 14 (4.8) |

| Read-write | 20 (6.9) |

| Grade 1to 8 | 56 (19.3) |

| Grade 9 to 12 | 98 (33.7) |

| Certificate and above | 102 (35.2) |

Table 2: Sociodemographic characteristics of husbands of respondents (for married and in the union) in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Obstetric Characteristics of the Respondents

The majority of pregnant women (93.8%) were gravid 1-4, and (41.8%) were primigravida. Out of the respondents, (11.5%) were experienced stillbirth (Table 3).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gravidity | |

| 1-4 | 319 (93.8) |

| >=5 | 21 (6.2) |

| Parity | |

| 1-4 | 169 (49.7) |

| >=5 | 29 (8.5) |

| 0 | 142 (41.8) |

| Stillbirth | |

| No | 301 (88.5) |

| Yes | 39 (11.5) |

Table 3: Obstetric characteristics of pregnant women who visited Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Antenatal Care Clinic Visit and Counseling about BPCR

From a total of 340 pregnant women, 97.8% started advice about BP/CR during their first and second ANC visits. A total of 74.4% of partners were counseled on BP/CR (Table 4).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Partners counseled | |

| No | 75 (25.6) |

| Yes | 215 (74.4) |

| Receive BP/CR counseling | |

| No | 7 (2.2) |

| Yes | 333 (97.8) |

| BPCR counseling started during | |

| 1st ANC visit | 291 (87.4) |

| 2nd ANC visit | 42 (12.6) |

Table 4: Pregnant women attending antenatal care clinics counseled on BP/CR in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Knowledge of the Respondents about Danger Signs that can Happen During Pregnancy and Childbirth/Labor

Out of 340 pregnant women, 5 (1.5%) participants did not mention any danger signs of pregnancy. Nearly half of them (50.6%) mentioned two or more danger signs, and (49.4%) mentioned only one key danger sign. Of the key danger signs, (84.4%), (50.9%) and (23.8%) vaginal bleeding, blurred vision, and swollen face or hand were mentioned, respectively (Table 5).

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| During pregnancy | Yes | No |

| Vaginal bleeding | 287 (84.4) | 48 ( 14.1) |

| Severe headache | 276 (81.2) | 59 (17.4) |

| Convulsion | 80 (23.5) | 255 (75) |

| High fever | 143 (42.1) | 192 (56.5) |

| Loss of consciousness | 72 (21.2) | 263 (77.4) |

| Blurred vision | 173 (50.9) | 162 (47.6) |

| Swollen hand/face | 81 (23.8) | 254 (74.7) |

| Difficulty of breathing | 49 (14.4) | 286 (84.1) |

| Severe weakness | 52 (15.3) | 283 (83.2) |

| Severe abdominal pain | 51 (15) | 284 (83.5) |

| Reduced fetal movement | 65 (19.1) | 270 (79.4) |

| Leakage of liquor | 135 (39.7) | 200 (58.8) |

| During labor/child birth | ||

| Vaginal bleeding | 285 (83.8) | 50 (14.7) |

| Severe headache | 189 (55.5) | 146 (43) |

| Convulsion | 115 (33.8) | 220 (64.7) |

| High fever | 73 (21.4) | 262 (77.1) |

| Loss of consciousness | 55 (16.1) | 280 (82.4) |

| Prolonged labor | 227 (66.8) | 108 (31.7) |

| Retained placenta | 294 (86.5) | 41 (12) |

Table 5: Knowledge of pregnant women on danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth/labor in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Knowledge and Practice of Pregnant Mothers on Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

Among pregnant mothers, (56.2%) were prepared for birth and its complications. Of these (89.1%) reported that they saved money, (86.5%) identified a place of delivery, and (57.4%) identified a mode of transportation. Considering their responses, saving money (89.1%) was the most commonly identified component of birth preparedness and complication readiness (Table 6).

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness | Yes | No |

| Identify place of delivery | 294 (86.5) | 46 (13.5) |

| Save money | 303 (89.1) | 37 (10.9) |

| Prepare essential items | 295 (86.8) | 45 (13.2) |

| Identify skilled provider | 47 (13.8) | 293 (86.2) |

| Aware signs of emergency | 234 (68.8) | 106 (31.2) |

| Decision maker on her behalf | 44 (12.9) | 296 (87.1) |

| Arranging to communicate | 43 (12.6) | 297 (87.4) |

| Arranging emergency funds | 41 (12.1) | 299 (87.9) |

| Identify mode of transportation | 195 (57.4) | 145 (42.6) |

| Arranging blood donors | 43 (12.6) | 297 (87.4) |

| Identify nearest institution | 56 (16.5) | 284 (83.5) |

| VCT | 209 (61.5) | 131 (38.5) |

Table 6: Knowledge of pregnant mothers on birth preparedness and complication readiness in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Husbands’ Attitudes towards Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

Only 1(0.3%) husband disagreed regarding the care their wife received from trained health professionals in public health institutes (Table 7).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Husband’s attitude towards birth preparation for ahead | |

| Strongly agree | 167 (57.6) |

| Agree | 123 (42.4) |

| Disagree | 0 |

| Husband’s attitude toward receiving care from a trained health professional | |

| Strongly agree | 168 (57.9) |

| Agree | 121 (41.8) |

| Disagree | 1 (0.3) |

Table 7: Attitude of husbands (for women married and in the union) regarding BPCR in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Factors Associated with Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

Illiterate mothers were approximately five times less likely to be prepared for birth and complications than literate mothers with [AOR =5.013 (1.236, 20.329)].

Partners who did not advise and counseled during the ANC visit were two times less likely prepared for birth and its complications than advised and counseled partners with (AOR= 2.149 (1.061, 4.353)).

Inexperienced mothers with stillbirth were six times less likely prepared for birth and complication readiness compared with experienced mothers, (AOR= 6.484 (1.044, 40.254)).

Pregnant mothers who know the danger signs of pregnancy were three times more likely prepared for birth and its complications readiness than non-knowledgeable mothers, (AOR= 3.066 (1.628, 5.77)).

Pregnant mothers who knew the danger signs of childbirth/labor were three times more likely prepared for birth and its complication than non-knowledgeable mothers, (AOR= 3.106 (1.676, 5.75)). Young mothers (age group 15-24 years) were two times less likely prepared for birth and its complications than aged mothers (age group above 34 years), (AOR= 2.892(1.100, 7.60)) (Table 8).

| Variables | Birth preparedness/ complication readiness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | COR | AOR | p-value | |

| Age group | |||||

| 15-24 | 9 | 33 | 11.186 (6.689, 18.706) | 2.892 (1.100, 7.60) | 0 .031 |

| 25-34 | 95 | 93 | 9.375 (5.487, 16.154) | 1.756 (1.081, 5.80) | |

| >=35 | 84 | 26 | 1 | 1 | |

| Educational status | |||||

| Illiterate | 4 | 50 | 3.611 (8.286, 67.281) | 5.013 (1.236, 20.329) | 0.024 |

| Others | 187 | 99 | 1 | 1 | |

| Stillbirth | |||||

| No | 154 | 147 | 17.659 (4.181, 74.586) | 6.484 (1.044, 40.254) | 0.045 |

| Yes | 37 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Knowledge of danger signs of Labor | |||||

| Knowledgeable | 141 | 30 | 11.186 (6.689, 18.706) | 3.106 (1.676, 5.75) | < 0.001 |

| Not knowledgeable | 50 | 119 | 1 | 1 | |

| Knowledge of danger signs of pregnancy | |||||

| Knowledgeable | 142 | 30 | 11.495 (6.865, 19.249) | 3.066(1.628, 5.77) | 0.001 |

| Not knowledgeable | 49 | 119 | 1 | 1 | |

| Partner counseled | |||||

| No | 25 | 50 | 2.791 (1.705, 4.570) | 2.149 (1.061, 4.353) | 0.034 |

| Yes | 158 | 57 | 1 | 1 | |

Table 8: Factors associated with birth preparedness and complication readiness in Debreberhan town governmental health institutions, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2019.

Complications during pregnancy and childbirth are unpredictable, and every woman needs to be aware of the key danger signs of obstetric complications during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period [8]. Findings from this study revealed that nearly half of the respondents were aware of most danger signs in connection to pregnancy, labor/delivery, and postpartum.

In this study, 97.8% of pregnant women received BP/CR counseling, and 91.5% started counseling during their 1st ANC visits. Nearly half of them (46.5%) had their first ANC visit in the first three months of pregnancy. According to the 2016 EDHS, 62% (age 15- 49) receive ANC from a skilled provider. One in five women has their first ANC visit in the first trimester, as recommended [4]. The current findings are higher than those of EDHS 2016, and a study from Adigrat town. This difference might be explained by the difference in the study period, socioeconomic characteristics, health service delivery, study area, and age difference. It may also be due to the increased awareness creation done by HEWs and it might also be due to the setting of the study.

The key danger signs during pregnancy include severe vaginal bleeding, swollen face or hands, blurred vision, severe vaginal bleeding, prolonged labor (>12hrs), convulsions, and retained placenta [1]. In this study, 1.5% of pregnant women did not mention any danger signs of pregnancy. This finding might be due to the study participants being interviewed during their first visit before advice and counseling were given. In this study, 50.6% of respondents mentioned two or more danger signs during pregnancy, and 49.4% mentioned only one key danger sign. In this study, the knowledge of respondents about key danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth/labor was 50.6% and 50.3%, respectively. However, the findings are consistent with the studies conducted in Dire Dawa, Dilchora referral hospital, 58.6%, and 51%, respectively [7]. This similarity might be due to the setting of the study, both conducted in health facilities. In both studies, the findings still indicate a low level of knowledge of key danger signs. These findings may indicate that less attention might have been given to key danger signs while providing health education and advice during ANC.

In this study, 56.2% were prepared for birth and its complications. Of these, 89.1% reported that they saved money, and 86.5% identified the place of delivery. Different findings on the practice of BP/CR showed that 22% of women participants from Tigray [6], 16.5% from Robe [8], 23.3% from Jimma, 17% from SNNPR [9], 54.7% from Dire Dawa [10], 68.6% from Addis Ababa [11], and 30% from Goba [12] were found to have made BPCR plans. These findings are relatively consistent with a study conducted in Dire Dawa. However, this finding is far higher compared to studies from Tigray, Robe, Jimma, and SNNPR. This difference might be due to the difference in the study period, socioeconomic characteristics, health service delivery, study area, and age difference. This might also be because this study was conducted in an urban setting with populations who have better access and awareness of health information. The other possible explanation for the higher level of BP/CR in this study might be due to the setting of the study, which was an institutional-based study. The finding is very low compared to a study conducted in Addis Ababa. This discrepancy might be due to the study area which was conducted in the capital city of Ethiopia.

Identification of the place of delivery is very important to obtain a skilled provider to deliver at health institutions. Lack of money and transportation is a barrier to seeking care as well as identifying and reaching medical facilities. The money saved by a woman or her family can pay for health services and supplies, vital transport, or other costs such as loss of work. Even when money is available, it can be difficult to secure transport at the last minute after a complication has occurred. Arranging transport ahead of time reduces the delay in seeking and reaching services [11]. In this study, 89.1% of respondents planned to save money, and 57.4% planned to arrange transport. However, only 12.6% planned to arrange blood donors. This finding contradicts the study conducted in the Sidama Zone, South Ethiopia in 2007, in which 34.5% planned to save money, 7.7% planned to arrange transport, 2.3% planned to arrange blood donors, and 8.1% planned to deliver in health facilities [13]. This difference might be explained by the difference in socioeconomic status, level of knowledge, and education. Since birth preparedness and complication readiness is relatively a recent strategy, service providers and program planners might have given special attention to the study setting. The overall status of birth preparedness and complication readiness in this study was 56.2%. This finding is different from studies conducted in Jimma town, Adigrat, and Sidama zone, where the status of BP/CR was 23.3%, 22%, and 17%, respectively [6,13]. This finding is far higher compared to studies in Jimma town, Adigrat, and Sidama zone. This difference might be due to the difference in the study period, socioeconomic characteristics, and health service delivery [13].

In this study, the age of pregnant mothers, level of educational status, knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth, and history of stillbirth were significantly associated with preparation for birth and its complications. This study is similar to other studies conducted in this country and abroad in which knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth were among the strong predictors of BP/CR practice [6,13]. This might be due to advice about the risks of pregnancy and the importance of BP/CR given during ANC. Health education during ANC also increases knowledge of danger signs and develops a favorable attitude that enhances preparation for birth and its complications.

More than half of the study participants had plans for birth preparedness and complication readiness, but their preparations were not comprehensive. Maternal literacy, knowledge of danger signs during pregnancy and childbirth, history of stillbirth, family monthly income, age, and advice given to partners on birth preparedness during ANC follow-up were found to be strong determinants of birth preparedness and complication readiness.

Based on our findings; the following will be recommended, health professionals working in Debre Berhan town public health institutions should provide adequate health education and promotion activities to enhance the awareness of pregnant mothers regarding the importance of birth preparedness and complication readiness. A nationwide, prospective, community-based study should be conducted to investigate the actual readiness for birth and complications. This study has the following limitations, because it is an institution-based study, and might not reflect the true rate of BP/CR practice in the community. In addition, this study was a cross-sectional study, and establishing a cause and effect relationship is difficult. Since the data collectors were health professionals, there may be some social desirability bias for some of the variables.

Data Availability

All data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Submitting authors are responsible for coauthors declaring their interests.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Debreberhan University for its kind cooperation in conducting this study.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Citation: Asefa A (2022) Knowledge and Practice on Birth Preparedness, Complication Readiness among Pregnant Women Visiting Debreberhan Town Governmental Health Institutions, North-East Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care 11:587.

Received: 13-May-2022, Manuscript No. JWH-22-17486; Editor assigned: 16-May-2022, Pre QC No. JWH-22-17486(PQ); Reviewed: 30-May-2022, QC No. JWH-22-17486; Revised: 03-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JWH-22-17486(R); Published: 10-Jun-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0420.22.11.587

Copyright: © 2022 Asefa A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.