Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2023)Volume 12, Issue 3

Background: Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among Ethiopian women. Women living with human immunodeficiency virus are more likely to develop an increased risk of invasive cervical cancer. Despite many interventions being conducted, cervical cancer screening services have low uptake. Also, limited evidence is available on the women’s intention and associated factors to use cervical cancer screening services among women living with the Human immune deficiency virus.

Objective: To assess the magnitude of intention to use cervical cancer screening service and associated factors among HIV-positive women who attends Anti-retroviral therapy clinic in East Gojjam public Hospitals, 2022.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study design with a systematic random sampling technique was used to recruit 424 women from May 1 to June 30, 2022. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews and chart review using a structured questionnaire. Data were entered in epi-data and exported and analyzed using SPSS version 25 software. Variables at a P-value < 0.25 in binary logistic regression were fitted to multivariable logistic regressions. The odds ratio at 95% CI was used to measure the strength of association at a p-value <0.05.

Results: A total of 417 women participated making a response rate of 98.3%. The magnitude of intention to receive cervical cancer screening was (58.3%), 95% CI= 53.4%- 63.1%). The factors associated with intention were women who have no children (AOR= 2.94, 95%CI: 1.20-7.25), patients with opportunistic infection (AOR=2.12 95%CI: 1.21-4.40); with good knowledge (AOR=2.30, 95% CI: 1.51-3.51); positive Attitude towards cervical cancer screening (AOR=1.53, 95%CI:1.13-2.29); positive subjective norm (AOR=1.53,95%CI, 1.32-2.11) and also respondents with higher PBC were more likely to have the intention to use cervical cancer screening service than counterparts (AOR=1.35,95%CI: 1.51-2.71).

Conclusion and Recommendation: In this study more than half of the participants have the intention to use cervical cancer screening services. Positive Attitude towards the behaviour, positive subjective norm, high Perceived behavioural control, good knowledge of cervical cancer, women who have no children, and a history of opportunistic infection were the predictors of intention. Hence, behavioural change communication interventions are important to change their attitude and empower them to evaluate their control and normative beliefs.

Cervical Cancer, Intention, HIV Positive, TPB, Ethiopia

CC: Cervical Cancer; CCS: Cervical Cancer Screening; HPV: Human Papilloma Virus; NGO: Non-Governmental Organization; PBC: Perceived Behaviour Control; SD: Standard Deviation; SPSS: Statistical Product for Social Service; TPB: Theory of Planned Behavior; VIA: Visual Inspection with Acetic acid; WHO: World Health Organization

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer in women and it is anticipated to kill over 443,000 women by 2030 the most of them are believed to occur in developing countries mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa. About 604,127 new cervical cancer cases are diagnosed annually and it is the most common cancer in women aged 15 to 44 years in the World. Corresponding to the World Health Organization (WHO), in areas where HIV is aboriginal, cervical cancer screening (CCS) results become positive for precancerous lesions in 15–20% of the target population [1-3].

In sub-Saharan Africa, cervical cancer directions are on the increasing in the past two decades because of HIV and this has rebounded in an increase in cervical cancer cases among youthful women. Cervical cancer is a public health concern and a leading cause of cancer-related death in low and middle-income countries. In Ethiopia, cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women’s, with an estimated 7745 new cases and 5338 deaths in 2020 [4-9].

Of all Cervical cancer(CC) cases throughout the world, seventy percent are caused by only two types of human papillomavirus (HPV); HPV-16 and HPV-18, and women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have a higher prevalence of HPV along with infection with multiple high-risk HPV types [10].

The burdens of cervical cancer have increased in majorly lowresource settings due to the adverse effects of HIV. This is due to the high threat of pre-invasive cervical lesions among HIV-positive women due to the high threat of HPV and vulnerable compromised status [11-15]. Research carried on the resource-limited country and Nigeria showed that 6% and 26.7% of HIV-positive women were diagnosed with pre-cancer respectively [16, 17]. And in our country, in southern Ethiopia and Amhara regional state, precancerous cervical cancer lesion among HIV-infected women was prevalent (22.1% and 9.9%) independently [18, 19].

Despite the advanced threat of developing cervical cancer, a study in Ethiopia shows lower than 20% of HIV-positive women was screened for cervical cancer, which is much lower than the public target (80%) of cervical cancer screening. And also, use of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women was low [20- 23].

This low utilization is due to different personal factors including poor knowledge of the prevention of cervical 423wwa*..0cancer; low threat comprehensions, negative health beliefs, and poor health-seeking actions were major barriers for women seeking cervical cancer screening. In addition to this; social networks, sociocultural morals, and also the stigma associated with HIV were major factors [24, 25].

This factor leads to delayed treatment-seeking behaviour with advanced stages of the disease and is common in developing countries and could markedly lead to a diminished chance of success of treatment even with multiple modalities [21]. Besides morbidity and mortality; cervical cancer also affects Quality of life, psychosocial effects, and economics. This is another burden for women living with HIV [26].

Progress in the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer has been made but challenges still exist in developing countries [27]. As Cervical cancer is a potentially preventable form of cancer, integrating screening programs into already existing HIV services to enable early detection and effective treatment can reduce morbidity and mortality [28, 29]. Different guidelines and strategies were developed; like Sustainable development goal 3.7; planned by 2030, to ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services by integrating reproductive health into national strategies and programs. Additionally; WHO developed a comprehensive global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer among women in all countries in 2030(3). According to revised WHO guidelines, sexually active and HIVpositive women are suggested to be screened every 3 to 5 years regardless of their age [30]. Ethiopia also adopted the WHO recommendation in 2015 and recommended HIV-positive women start screening at HIV diagnosis, regardless of age and more emphasis was given to programs focusing on the early detection of cervical cancer [13].

Creating a favourable attitude towards Screening behaviour and general health-seeking behaviour related to prevention services is one way to increase service utilization at the early stage [21]. Cervical cancer screening interventions for HIV-positive women need to have a strong focus on explaining the seriousness of the disease and the benefits of screening. Improving attitude toward cervical cancer screening and promoting the health of high-risk women is important [31].

Understanding the competing and motivating factors affecting CCS behaviour among women in the context helps to enhance the screening and treatment efforts. Considering individual health needs, concerns and their decision-making process are imperative to understand the health-seeking behaviour toward any healthrelated conditions. Several theoretical frameworks or models have been developed that could help to explain individual health-seeking behavioral changes [32]

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) which is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), is one of the most commonly used social-cognitive theories to understand and predict intention and behaviors [33]. According to the TPB, attitude towards behavior, subjective norms (general perception of social pressure to do), and perceived behavioural control (PBC) determine intention which in turn predicts the behaviour [34].

A previous study conducted in Ethiopia was not emphasized on cognitive dimensions of HIV-positive women [19, 35, 36]. Therefore, this study addressed the complex normative dimensions and circumstances that importantly influence the women's decision-making process and intention to use CCS and associated factors among HIV-positive women.

Study design, area and period

The institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted in public Hospitals in the East Gojjam zone. It is one of the 13 zones in the Amhara National Regional State. And its capital town is Debre Markos which is located 300 km northwest of Addis Ababa to Northern and 265 km from Bahir Dar which is the capital city of Amhara Regional State. East Gojjam zone has a total area of 13809 km2. There are ten hospitals, in this zone. Currently, 4698 women are registered in the public hospital and actively following in the ART clinics. Among those 2550 women are screened but the rests were not screened. All Hospitals are providing screening services; it was conducted from May 1 to June 30, 2022.

Population

Source population: all HIV-positive women who were on ART follow-up in East Gojjam zone Public Hospitals.

Study population: all HIV-positive women who attended ART follow-up clinics during the study period were study populations.

Inclusion: All selected HIV-positive Women who come to the ART clinic during the data collection period were included.

Exclusion criteria: the HIV-positive woman who had previously been screened was excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

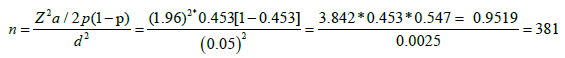

The sample size for this study was calculated using a single population proportion formula with the following assumptions 95 % confidence interval (a=0.05), 5 % margin of error (d) and the proportion (p) of intention to cervical cancer screening in women from a previous study conducted Debre Berhan was (45.3%) which gave maximum sample size.

0.0025 and by adding 10% non-response rate (NR); final sample size is, (NF) = Ni × 1/ (1-NR) =381 × 1/ (1-0.1) =424

Sampling procedure and techniques

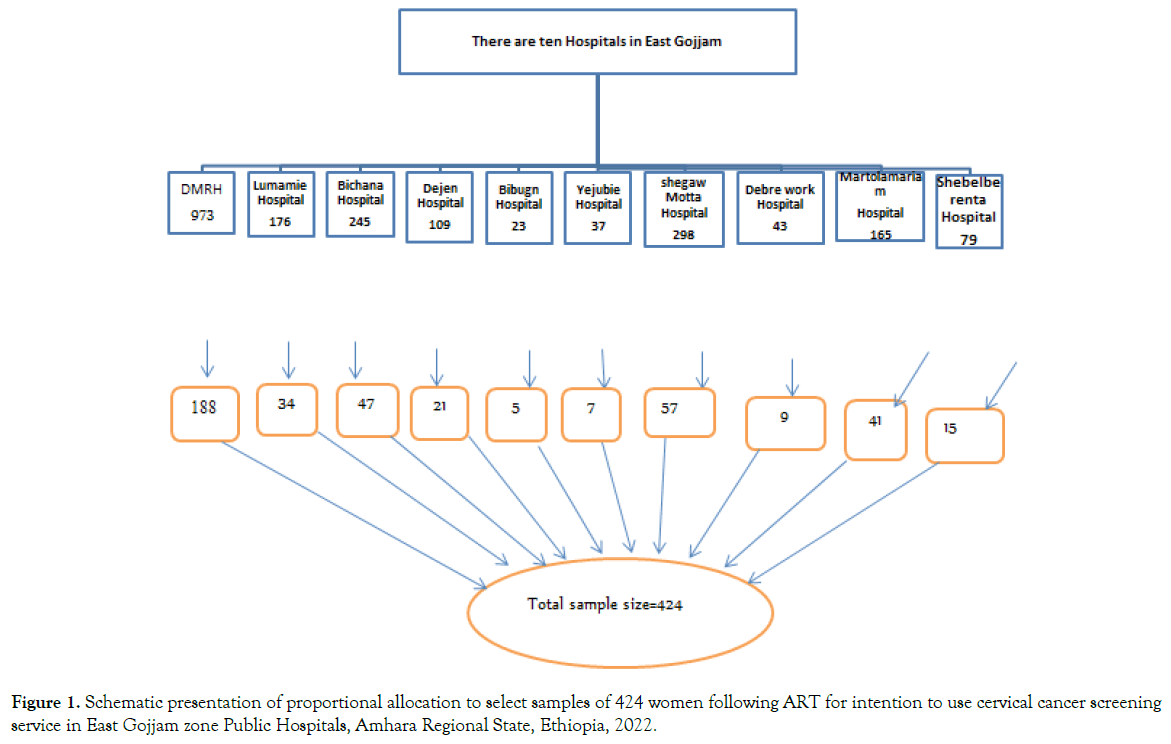

Ten public Hospitals in the East Gojjam zone are providing cervical cancer screening services. The calculated sample size was proportionally allocated based on the number of women unscreened to each Hospital. Then study participants were selected by using a systematic random sampling technique with a k-value of 3 (by dividing the total unscreened by sample size) until the required sample size was reached; lottery methods were used to select between 1 and 3 participants. So; every third woman who comes to ART follow-up in each hospital was included and the interview was conducted before entry in a separate room (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of proportional allocation to select samples of 424 women following ART for intention to use cervical cancer screening service in East Gojjam zone Public Hospitals, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia, 2022.

Variables

Dependent variable: Intention to use cervical Cancer Screening service

Independent variable: Socio-demographic variables: Age, religion, educational status, occupational status, monthly income, Ethnicity, Marital status, husband’s educational status, husband’s occupational status; Theory of Planned Behaviour constructs: Attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control; Obstetrics related factors: Living children; knowing woman’s who developed cervical cancer; Knowledge related risk factors and symptoms to cervical cancer; Health and treatment-related variables: duration of ART follow up, CD4 count, stages of HIV, history of opportunistic infection.

Operational-definitions

Intention: Intention is an internal mental state that denotes a determination to carry out a specific action or series of activities in the future [37]. The overall intention score was determined by calculating the mean score. The woman who scored greater than or equal to the mean intention score (3.84) was said to have an intention to screen for cervical cancer and no intention if they scored below the mean intention score [38].

The attitude: Respondents who scored greater than or equal to the mean attitude value (3.65) were considered to have a favorable attitude and respondents who scored below the mean attitude value were considered to have an unfavorable attitude towards CCS [39].

Subjective norm: It is the perception of the social pressure to receive cervical cancer screening service or not, and respondents who scored above the mean (3.25) subjective norm value were considered to have positive subjective norms, and respondents who scored below the mean subjective norm value were considered to have negative subjective norms on CCS [40,41].

Perceived Behavioural Control: It is an individual's perception of the ease or difficulty of performing a particular behaviour or one’s feeling that how much doing or non-doing a behaviour is voluntarily controlled [32]. Respondents who scored above the mean PBC value (3.32) were considered to have higher PBC on CCS and respondents who scored below the mean PBC value were considered to have lower PBC on CCS [42].

Knowledge: item scores were added up to get overall knowledge scores, individuals who rightly answered the item were given a value of "1" and those who answered inaptly were valued "0" and the mean and standard deviation were calculated. Women with a summary score greater than or equal to the mean (10.6) value were categorized as having "good knowledge" and those with a score less than the mean were categorized as having “poor knowledge [43].

Measurement and scoring

Each of the direct constructs of TPB (direct attitude, direct subjective norm, and direct perceived behavioural control) and intention towards cervical cancer screening was measured using four items with five points on the Likert scale. For each construct, the response variables were calculated by summing up the responses obtained under their four items.

Direct attitude; It was measured using four semantic scale type items with five scales; a higher score indicates a stronger attitude towards receiving cervical cancer screening. Direct subjective norm; was assessed using four Likert-type items and a higher score indicates subjective norms encouraging undergoing cervical cancer screening. Direct perceived behavioral control; is the perceived ability of an individual to control factors that influence cervical cancer screening. It was assessed using four scale type items and a higher score indicates controlling more perceived behavior to undergo cervical cancer screening.

Indirect TPB model variables were also measured by Likert-type items. Indirect attitude; is composed of behavioural belief, i.e one’s belief about the likely outcome of up taking cervical cancer screening and outcome evaluation, i.e; one’s judgmental evaluation of the outcome of the behavior. It was measured by ten Likert-type items, five items from behavioral belief, and five from outcome evaluation. Indirect subjective norm; It is a combination of normative belief, i.e, one’s belief about what significant others think that she should or should not uptake cervical cancer screening or behavior in question, and one's readiness to perform the behavior in the way that significant others want her to do. It was measured using twelve Likert-type items, six items from normative belief, and six from motivation to comply. Indirect perceived behavioral control; is also a combination of once control belief (seven items), ie, belief about the facilitators/barriers to cervical cancer screening uptake and power to control those control beliefs (seven items).

Data collection tools and procedures

An interviewer-administered face-to-face interview and chart review were carried out. The questionnaire was developed after reviewing applicable literature and based on the theory of planned behavior. In addition to constructs of TPB, socio-demographic information and knowledge about cervical cancer were addressed. The first questionnaire was prepared in English and restated to Amharic (local language) and back-translated to English. Ten BSc Midwives for data collection and two BSc midwife supervisors were recruited from near to the hospital.

The TPB constructs were adopted from the standard tool that is developed based on the theory of planned behaviour [44, 45]. Twelve items were adopted to measure the three constructs (attitude towards CCS, subjective norm about CCS, and PBC of CCS). All particular item responses have unipolar Likert scales of 1 to 5.

Data quality assurance

To maintain the quality of data; standardized data collection tools were used. And its validity and reliability was checked in former studies conducted among childbearing-age women to assess intention to use cervical screening services in Bahir Dar and Debre Berhan [45-48]. In this study reliability of the instruments was computed with the help of the SPSS software and Cronbach's alpha was computed to establish internal consistency on the Likert scale questions. As a result, Cronbach's alpha of was 0.71. The applicable one-day training was given for both data collectors and supervisors on clarification of assessment tools; the aim of the study, concerning the need for strict confidentiality of respondent’s information and submission on due time and supervision, was carried out by supervisors to check the completeness of the questionnaire.

Pre-tested was done with 22(5%) HIV-positive women who met the study criteria at Finote Selam General Hospital which is not part of the study to ensure consistency and completeness of the questionnaire. Codes were given to the questionnaires during data collection. The completeness of the collected data was checked by the data collectors and supervisor on daily basis. Furthermore, Statistical control during data analysis was used to reduce the influence of confounding factors.

After data collection, it was coded and entered into Epi-info version 3.1 and then exported to SPSS 25 statistical software package for analysis. Descriptive statics of continuous variables was presented using mean and discrete variables was presented using percentage and tables. Binary logistic regression analysis was done to assess the association between all independent variables with intention. All variables at a P-value less than 0.25 in bi-variable logistic regression were fitted to multiple logistic regressions and identified the independent factors of intention. The goodness of fit of the regression model analysis was checked by using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test (0.621). A significant independent factor was declared at a 95% confidence interval and a P-value less than 0.05 was used as a cut-off point of statistical significance. The multi-collinearity was checked by the variance inflation factor and the result was less than two.

The study offer was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Debre Markos University. A letter from the Research Ethics Committee was submitted to each public Hospital to get authorization for conducting the study. To protect the confidentiality of the participants, both data collectors and supervisors were interviewed in separate ART counselling rooms; in addition, personal identifier data was not collected. Informed verbal concurrence was attained from repliers after explaining the purpose of the study.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

A total of 417 respondents participated in this study, making a response rate of 98.3%. The mean age of the participants was 34.76years (SD±7.24 years). The majority of 408(97.8 %) study participants were orthodox Christian religious followers. Out of the total participants, 206(49.4%) of them reported that their main occupation was farming activities. Regarding marital status majority of the women, 330(79.1%) was married and 123 (29.5%) study participants had primary education (Table 1).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 | 19 | 4.6 |

| 25-34 | 197 | 47.2 | |

| 35-44 | 152 | 36.5 | |

| >=45 | 49 | 11.8 | |

| Religion | Orthodox Christian | 408 | 97.8 |

| Muslim | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Protestant | 6 | 1.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 330 | 79.1 |

| Single | 45 | 10.8 | |

| Divorced | 37 | 8.9 | |

| Widowed | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Educational status of the respondent | Unable to read & write | 86 | 20.6 |

| able to read & write | 81 | 19.4 | |

| Primary school | 123 | 29.5 | |

| Secondary school | 63 | 15.1 | |

| College & above | 64 | 15.3 | |

| Occupation respondent | Government employee | 52 | 12.5 |

| Private employee | 21 | 5.0 | |

| Marchant | 15 | 3.6 | |

| Farmer | 206 | 49.4 | |

| Housewife | 123 | 29.5 | |

| Educational status of husbands | Unable to read & write | 59 | 14.1 |

| able to read & write | 36 | 8.6 | |

| Primary school | 140 | 33.6 | |

| Secondary school | 48 | 11.5 | |

| College and above | 47 | 11.3 | |

| Occupations of husband | Government employee | 64 | 15.3 |

| Private employee | 17 | 4.1 | |

| Merchants | 23 | 5.5 | |

| Farmer | 226 | 54.2 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of women who visit east Gojjam public Hospital for ART follow-up in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, 2022 (n=417)

Obstetric and Health-related characteristics

Regarding the number of children majority of respondents had children one to four. Among all respondents, 403(96.6%) of them did not know a woman who developed cervical cancer and more than half of the respondents were in, WHO stage one of HIV (Table 2)

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of live children | No child | 47 | 11.3 |

| 1-4 | 319 | 76.5 | |

| 5 and above | 51 | 12.2 | |

| Knowing persons who developed cervical cancer | Yes | 14 | 3.4 |

| No | 403 | 96.6 | |

| Duration of ART follow-up (year) | <4 | 310 | 74.3 |

| 4-8 | 97 | 23.3 | |

| >=8 | 10 | 2.4 | |

| History of opportunistic infection | Yes | 35 | 8.4 |

| No | 382 | 91.6 | |

| Baseline WHO Stages of HIV | Stage 1 | 340 | 81.5 |

| Stage 2 | 53 | 12.7 | |

| Stage 3 | 24 | 5.8 | |

| Recent CD4 count | < 500 | 219 | 52.5 |

| >=500 | 198 | 47.5 |

Table 2. Obstetric and Health-related characteristics of women who visit east Gojjam public Hospital for ART follow-up in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, 2022 (n=417)

Knowledge related to cervical cancer prevention and symptom

In this study, 222 (53.2%) respondents who had good knowledge scored greater than or equal to the mean (>=10.6) value at Std. Deviation 2.37 whereas, 195 (46.8%) of the respondents who had poor knowledge scored less than the mean. Of all study participants, 324(77.7%) had heard about cervical cancer. Of those who had heard about cervical cancer, 169 (40.5%) participants were heard from health care professionals. More than two-thirds of 291(69.1%) respondents Know that cervical cancer can be caused by the unsafe sexual practice. Regarding symptoms of cervical cancer, 225(54.0%) and 180(43.2 %) of them mentioned pain and bleeding after sexual intercourse and foul-smelling vaginal discharge were symptoms of cervical cancer respectively. Two hundred four (48.9%) of study participants responds that cervical cancer is curable if it is treated in its earliest stage (Table 3).

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heard about cervical cancer | Yes | 324 | 77.7 |

| No | 93 | 22.3 | |

| Source of information | Mass-media | 91 | 21.8 |

| Friends/family | 131 | 31.4 | |

| Health care professional | 169 | 40.5 | |

| Health extension worker | 154 | 36.9 | |

| Cervical cancer caused by unsafe sexual practice | Yes | 291 | 69.8 |

| No | 27 | 6.5 | |

| I Do not know | 99 | 23.7 | |

| Symptoms of cervical cancer | Pain or bleeding after sexual intercourse | 225 | 54.0 |

| Post-menopausal bleeding | 141 | 33.8 | |

| Excessive vaginal discharge | 180 | 43.2 | |

| Abnormal bleeding between periods | 126 | 30.2 | |

| Cervical Cancer is a preventable disease | Yes | 273 | 66.4 |

| No | 41 | 13.1 | |

| I don’t know | 103 | 20.5 | |

| Prevention of cervical cancer | regular medical check-ups/screening | 195 | 46.8 |

| vaccine for HPV | 165 | 39.6 | |

| delaying sexual debut | 78 | 18.7 | |

| consistent condom use | 132 | 31.7 | |

| early detection of cervical cancer is good for treatment outcome | yes | 214 | 51.3 |

| No | 39 | 9.4 | |

| I don’t know | 164 | 38.8 | |

| Cervical cancer is better to be cured at | Early | 204 | 48.9 |

| Late | 39 | 9.4 | |

| Not curable at any time | 81 | 19.4 | |

| Curable at any time | 42 | 10.1 | |

| I do not know | 51 | 12.2 |

Table 3. Knowledge about risk factors, presenting symptoms, and preventions of cervical cancer among women who visit East Gojjam Public hospitals in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, 2022 (n=417)

Magnitude of intention to use Cervical Cancer screening service

The mean value of intention score was 3.83 at standard deviation ±0.71 and more than half of 243 (58.3%, CI=53.4- 63.1%) respondents scored above the mean, that they have the intention to use cervical cancer screening service in the next three months from date of data collection.

Concerning the direct components of the theory of planned behavior, about 229(54.9%), of women have a positive attitude with a mean score of 3.65 ± 0.68, followed by perceived behavioral control of about 210(50.4%) of women have high PBC with a mean score of (3.32; SD 0.65) (Table 4).

| Components | No of items | Min. value | Max. value | Mean | SD | Collinearity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | ||||||

| Direct attitude | 4 | 1.75 | 5.00 | 3.65 | 0.68 | 1.053 |

| Direct Subjective | 4 | 1.50 | 5.00 | 3.25 | 0.69 | 1.105 |

| Direct PBC | 4 | 1.25 | 4.75 | 3.32 | 0.65 | 1.117 |

| Intention | 3 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.84 | 0.71 | |

| Indirect attitude = ∑Behavioral belief (BB) * Evaluation of behavioral belief (EBB) | 10 | 2.60 | 4.70 | 3.96 | 0.40 | 1.149 |

| Indirect subjective Norm= ∑ Normative belief(NB) *Motivation to comply (MTC) | 12 | 2.83 | 4.67 | 3.78 | 0.34 | 1.150 |

| Indirect PBC= ∑Control belief (CB) *Power of control belief (PCB) | 14 | 1.42 | 5.17 | 3.05 | 0.76 | 1.079 |

Table 4. Descriptive statistics for the components of the theory of planned behavior model and women’s intention to use cervical cancer screening service among women on ART East Gojjam Public hospitals in East Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, 2022 (n=417)

Factors associated with intention to use cervical cancer screening service

Bi-variable analyses were done between dependent and independent variables. Variable like age, marital status, maternal educational and occupational status, husband educational and occupational status, number of live children, history of opportunistic infection, stages of HIV, durations of ART follow-up, CD4 count, knowledge of cervical cancer, direct (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control) and indirect (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control) were tested in bi-variable logistic regression. Among these Variables: age, maternal education, occupational status, number of children, History of Opportunistic infection, stages of HIV, CD4 count, Knowledge of cervical cancer, direct (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioural control), and indirect (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control) were significant variables in bi-variable logistic regression at P-value of ≤ 0.25.

Multi-variable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with intention to use cervical cancer screening service

Variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 from the bi-variable analysis were entered into multivariable analysis to identify the significant associated factors for intention to screen for cervical cancer at a p-value of less than or equal to 0.05. Accordingly, as described in Table 5, the associated factors for intention among HIV patients taking ART were; the number of children, the odds of cervical cancer screening intention were increased by 2.9 times in women who have no children than in women who have more than five children (AOR= 2.94, 95%CI: 1.20-7.24). The likelihood of having an intention for cervical cancer screening was 2.1 times higher among women who had a history of opportunistic infection than their counterparts (AOR=2.12 95%CI: 1.21-4.40); women who had good Knowledge were 2.3 times more likely to have intention than woman's who had poor knowledge (AOR=2.30, 95% CI: 1.52-3.51); odds of patients with positive Attitude were 1.5 times more likely had intention than counterpart (AOR=1.53, 95%CI:1.13-2.29); odds of women's having positive subjective norm were also 1.7 times more likely had intention than woman’s who had negative subjective norms(AOR=1.53,95%CI, 1.32-2.11) and also odds of respondents with higher PBC were 1.3 times more likely have the intention to use cervical cancer screening service than the respective referent group (AOR=1.35,95%CI: 1.51-2.71) .

| Variables | Intention | Odds ratio (95 %CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have intention | Have no intention | COR | AOR | ||||

| Ages of respondents | |||||||

| 15-24 | 15 | 4 | 2.18(.626-7.573) | 2.5(.738-9.520) | 0.135 | ||

| 25-34 | 108 | 89 | 0.71(.370-1.343) | 0.82(.376-1.394) | 0.334 | ||

| 35-44 | 89 | 63 | 0.82(.422-1.694) | 0.78(.396-1.536) | 0.472 | ||

| >=45 | 31 | 18 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Educational status of respondents | |||||||

| Unable to read and write | 41 | 45 | 0.45(.230-0.871) | 0.60(0.220-1.632) | 0.318 | ||

| Can read and write | 43 | 38 | 0.55((.280-1.091) | 0.65(0.230-1.248) | 0.421 | ||

| Primary | 78 | 45 | 0.85(.447-1.602) | 1.07(0.402-2.837) | 0.896 | ||

| Secondary | 38 | 25 | 0.74(.359-1.534) | 0.86(0.384-2.139) | 0.735 | ||

| College and above | 43 | 21 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Occupations of respondents | |||||||

| Government employee | 36 | 16 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Private | 11 | 10 | 0.49(.173-1.382) | 0.67(0.218-2.084) | 0.493 | ||

| Merchant | 12 | 3 | 1.78(.440-7.177) | 1.83(0.424-7.885) | 0.419 | ||

| Farmer | 116 | 90 | 0.57(.299-1.097) | 0.96(0.435-2.077) | 0.899 | ||

| Housewife | 68 | 55 | 0.55(.276-1.093) | 0.97(0.430-2.183) | 0.940 | ||

| number of a live child | |||||||

| No children | 37 | 10 | 3.04(1.248-7.401) | 2.94(1.195-7.246) | 0.019* | ||

| 1-4 | 178 | 141 | 1.04(.572-1.879) | 0.63(0.412-0.951) | 0.952 | ||

| 5 and above | 28 | 23 | 1 | 1 | |||

| History of Opportunistic infection | |||||||

| Yes | 26 | 9 | 2.35(1.317-7.382) | 2.12(1.208-4.998) | 0.010* | ||

| No | 207 | 165 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Stages of HIV | |||||||

| Stage 1 | 210 | 130 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Stage 2 | 22 | 31 | 0.44(.244-.791) | 0.71(0.287-1.656) | 0.096 | ||

| Stage 3 | 11 | 13 | 0.52(.228-1.204) | 0.68(0.281-1.656) | 0.398 | ||

| Recent CD4 count | |||||||

| >= 500 | 118 | 65 | 1.58(1.064 -2.355) | 1.51(0.987-2.308) | 0.057 | ||

| Less than 500 | 125 | 109 | 1 | 1 | |||

| knowledge category | |||||||

| Good knowledge | 152 | 70 | 2.48 (1.665-3.699) | 2.30(1.508፟-3.511) | 0.001* | ||

| Poor knowledge | 91 | 104 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Direct constructs of TPB | |||||||

| favourable attitude | 153 | 91 | 1.55(1.044-2.302) | 1.50 (1.130-2.286 | 0.035* | ||

| Unfavorable attitude | 90 | 83 | 1 | 1 | |||

| High PBC | 130 | 77 | 1.45(1.980-2.143) | 1.35(1.510-2.710) | 0.045* | ||

| Low PBC | 113 | 97 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Positive Subjective norm | 122 | 66 | 1.65(2.452-1.110) | 1.53(1.325-2.109) | 0.020* | ||

| Negative subjective norm | 121 | 108 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Indirect constructs of TPB | |||||||

| Favourable indirect attitude | 146 | 91 | 1.37(1.927-2.134) | 1.25(1.347-2.022) | 0.010* | ||

| Unfavorable indirect attitude | 97 | 83 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Positive indirect SN | 149 | 76 | 2.04(1.376-3.035) | 1.85(1.223-2.810) | 0.040* | ||

| Negative indirect SN | 94 | 98 | 1 | 1 | |||

| High indirect PBC | 80 | 42 | 1.54(1.995-2.391) | 1.41(1.200-2.028) | 0.048* | ||

| Low indirect PBC | 163 | 132 | 1 | 1 | |||

Table 5. Multi-variable analysis of factors associated with intention to use cervical cancer screening service among women in ART follow-up in East Gojjam public Hospitals Debre Markos, Ethiopia, 2022

The current study assessed the magnitude and associated factors of intention to use cervical cancer screening services among HIVpositive patients by using the Theory of planned behaviour model.

The study found that 58.3% (95%, CI=53.4-63.1%) of the HIV patients taking ART had the intention to use cervical cancer screening service in the next three months from the date of data collection. When compared with other similar studies, the magnitude of intention in the current study area is comparable with a study conducted in Jimma, 57.3% [43].

The magnitude of the current study finding was slightly higher than a study conducted in Debre Berhan 43.4%. The difference in this finding might be due to participants of this study having more contact with health care providers and due to variation in access to information. Moreover, the finding of this study was consistent with findings conducted in Malawi 57.2%, Malaysia 56%, and 63% in Uganda had intention [39-41].

But other studies conducted in Canada 84% and Ghana 82% showed that the magnitude of intention was greater than the current study area. The reason for the such difference could be due to the difference in the socio-demographic characteristics, and socio-cultural variation towards health-seeking behaviors and most of the respondents of the former studies heard about cervical cancer and screening services introduced earlier in those countries [38,42]

In the current study, women's knowledge about cervical cancer was related to their intention of cervical cancer screening, and having good Knowledge was a positively associated factor. When compared with other studies conducted in Debre Berhan found that Knowledge of women on cervical cancer was significantly associated with intention of cervical cancer screening uptake [43]. This could be explained by patients having good knowledge of risk factors, their severity, and on prevention methods could be highly intended to screen at an earlier stage.

In this study women who had no children were more likely to have intention than a woman who had more than five children. This finding was similar to studies in Jinka, Ethiopia, and Dare Salaam; Tanzania that shows respondents who had two or fewer living children were more than two times more likely willing to be screened for cervical cancer as compared with women who had three or more children [9,49-52]. The reason for this might be due to women who have no children have the desire to get a healthy child and they may fear no child in the future if they haven't been screened and developed cervical cancer.

This study revealed that; respondents who had a positive attitude were significantly associated with an intention to screen for cervical cancer. Similar findings were also observed in studies by Debre Berhan, Bahir Dar and Jimma revealed that positive attitudes towards cervical cancer screening had a positive influence on women's intention to use cervical cancer screening services [43,45,48]. Current studies were also consistent with findings in China and western Iran which identified attitude toward cervical cancer screening as the most positive significant factor that affects intention to use cervical cancer screening services [46,47]. This finding indicates that creating a favorable attitude toward cervical cancer screening is necessary to minimize misperception and to enable people to use screening services at an early stage.

In addition, this study also revealed that respondents who had Positive subjective norms were 1.5 times more likely to have intention than a woman who had negative subjective norms. This finding similar to studies in Debre Berhan, Bahir Dar, and Jimma, showed that a positive subjective norm was a significant positive association with intention to use cervical cancer screen service [43,45,48]. Similarly, a study conducted in Singapore, Malaysia, and Tanzania found a high level of subjective norms significantly predicting cervical cancer screening intention [41,49,50]. Possibly this might be due to beliefs about the normative expectations of others and this results in perceived social pressure to use screening services.

The current study also showed that respondents with higher PBC were significantly associated and 1.3 times more likely to have the intention to use cervical cancer screening services than their counterparts. This finding was similar to the findings in Debre Berhan, Bahir Dar, and Southern Ethiopia: indicating that Perceived Behavioural Control was found to be the most important factor positively associated with the intention to screen for cervical cancer [45,48,51]. The current finding was also consistent with the studies in Latin-American that direct perceived behavioural control was positively and strongly associated with intention to use cervical cancer screening services [33]. This was consistent with the concept of TPB which stated that the more favourable (positive) attitude, positive subjective norm, and the greater the PBC the stronger should be the person's intention to perform the behaviour in question [53-57].

There might be a possibility for social desirability bias that might affect the study outcome; this might be mentioned as possible limitation for this study.

In this study more than half of woman’s have intention to use screening service, but several activities required from health professionals and patients. To increase intentions to use cervical cancer screening services acting on knowledge of possible risk factors for cervical cancer is important. Knowledge of risk factors and preventions of cervical cancer, number of children, History of opportunistic infection, Positive attitudes towards cervical cancer screening (CCS), subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control were predictors of women’s intention to screen for cervical cancer. This finding highlights the need for focused interventions on the intention to use cervical cancer screening service uptake to ensure the effectiveness and minimize cervical cancer mortality, especially in these high-risk groups of women. East Gojjam Zone health office better emphasizes behavioural change communication to improve women's intention on health-seeking behaviour towards cervical cancer screening focusing on the constructs theory of planned behaviour through different meetings and by using mass media. Health care providers better give special emphasis to women who have poor knowledge of risk factors and prevention methods of cervical cancer and further more researchers better conduct prospective studies to identify actual behaviours to use screening services within three months.

Conceptualization: Geremew Bishaw

Proposal: Geremew Bishaw,Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezew, Fekadu Baye, Habtamu Ayele, Gezhagn Aychew

Methodology: Geremew Bishaw, Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezaw, Fekadu Baye, Habtamu Ayele, Gezhagn Aychew

Formal analysis: Geremew Bishaw,Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezew

Validation: Geremew Bishaw, Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezaw, Fekadu Baye, Habtamu Ayele, Gezhagn Aychew

Writing- report: Geremew Bishaw, Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezaw Fekadu Baye, Habtamu Ayele, Gezhagn Aychew

Mnauscript preparation: Geremew Bishaw, Nurilign Abebe, Yibelu Bazezaw Fekadu Baye, Habtamu Ayele and Gezhagn Aychew involved in the manuscript preparation. And all authors read and permitted the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared there is no conflict of interest with respect to the research authorship, or publication of this article.

The authors are thankful for Debre-Markos University for the necessary funds, the data collectors, hospital administrators, ART unit staff, and study participants who participated in this study.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Citation: Bishaw G, Abebe N, Bazezew Y, Baye F, Ayele H, Aychew G (2023) Intention to Use Cervical Cancer Screening Service Among Womans Living With HIV Who Attends to ART Clinic, Amahara East Gojjam, Ethiopia 2022. J Women's Health Care. 12(2):630

Received: 31-Jan-2023, Manuscript No. JWH-23-21647; Editor assigned: 02-Feb-2023, Pre QC No. JWH-23-21647(PQ); Reviewed: 18-Feb-2023, QC No. JWH-23-21647; Revised: 23-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. JWH-23-21647(R); Published: 02-Mar-2023 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0420.23.12.630

Copyright: © 2023 Bishaw G et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited