Journal of Women's Health Care

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-0420

ISSN: 2167-0420

Research Article - (2021)

Objective: Obstetric fistula is a life-altering birth associated injury and it is indicative of a health system that has failed to provide appropriate intra-partum care. Therefore, this study aimed to assess factors associated with knowledge and the misconception of obstetric fistula among women in Northwest Ethiopia.

Method: Health facility based cross-sectional study was employed from March to April, 2019 among 395 pregnant women. The data were collected by systematic random sampling technique and analysed using SPSS 23.0 version. Logistic regression analyses was employed to estimate the crude and adjusted odds ratio with confidence interval of 95% and a P value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results: In this study, 41.3% of pregnant mothers had heard of obstetric fistula and among those mothers, 62.6% and 42.3% had good knowledge and misconceptions of obstetric fistula respectively. Living in urban [AOR=3.19, 95% CI=1.33-7.67], having history of antenatal visit [AOR=4.05, 95% CI=1.56-10.51], having primary educational level, secondary and above educational level, high monthly income, age at first pregnancy, institutional delivery, primiparity, multiparty, and contraceptive methods utilization were associated with knowledge of obstetric fistula. Whereas; had no formal education [AOR=4.01, 95% CI =1.51-10.65], living in rural and not using contraceptive methods were associated with the misconception of obstetric fistula.

Conclusion: In the present study, pregnant women who had knowledge of obstetric fistula low and the misconceptions of obstetric fistula was high. Therefore, there is a need to give more emphasis on addressing obstetric fistula messages about its risk factors and preventive methods.

ANC: Antenatal Care; AOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; COR: Crude odds ratio; PNC: Postnatal Care; SPSS: Statistical Package of Social Sciences; VVF: Vesico Vaginal Fistula.

Obstetric fistula is an abnormal opening in between the female genital and urinary tract and/or the gastrointestinal tract [1]. According to WHO 2014 report, globally an estimated amount of more than two million women living with untreated fistula and every year there are between 50,000 to 100,000 new cases of obstetric fistula develop worldwide [2]. Among all maternal morbidities, obstetric fistula has the most devastating effects on physical, social and economic levels and represents a major public health issue for women and in low income countries. However; it has been essentially eradicated in high-income countries [1,3-6]. The main direct causes of obstetric fistula is inadequately managed prolonged obstructed labor, which resulting in vaginal, bladder, and rectal damage due to compression of the maternal tissue by the fetus [3,7,8]. A woman with chronic incontinence and pain, unable to perform household chores and child-rearing as a wife, thus devaluing her. As a result, many women are divorced or abandoned by their husbands, disowned by family, marginalized by the society, develop mental health problems and commit suicide [9-15]. Because of continuous dripping, the acid in the urine causes severe burn wounds on the legs, this can result in nerve damage and cause the woman to struggle with walking and eventually lose mobility. In an attempt to avoid the dripping, the women limit her intake of water and liquid, which can ultimately lead dehydration, kidney disease and failure and lastly lead to death [15,16].

Others factors which contributing to obstetric fistula includes lack of education, and skilled birth attendants, poor health seeking behaviour, and transportation systems, inadequate facilities providing comprehensive obstetric care services, poverty, malnutrition and harmful traditional practices [8,12,16-19]. It is treatable by surgery as well as further by palliative care and can be prevented completely by providing competent emergency obstetric care throughout pregnancy, promoting education of girls and discouraging harmful traditional practice [2,5,6,20].

Knowledge on obstetric fistula risk factors in developing countries remains a great challenge, and despite the problems associated with it, many women are not know about this disease entity, and this makes them not be able to take practical steps in its prevention [18,21,22]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess factors associated with knowledge and the misconceptions of obstetric fistula.

Study Design and Period

Health facility based cross-sectional study design was employed from March to April, 2019 at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia.

Study Area

The study was conducted in Injibara town, Awi zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Injibara town is located about 447 km away from Addis Ababa the capital city of Ethiopia, and 118 km from Bahir Dar city of Amhara Region. The town has five Keeble’s with the total population of 46,745, of which 23,466 are females [23].

Source Population

All pregnant women who attended ANC at the public health facilities of Injibara town.

Study Population

Systematically selected pregnant women who attended ANC at the public health facilities of Injibara town.

Inclusive and Exclusion Criteria

Pregnant women who attended ANC at the public health facility of Injibara town were included. While pregnant women who revisited the ANC unit during the study period were excluded.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula by considering the following assumptions: knowledge of obstetric fistula among pregnant women in Ghana was 62.8% [24], Zα/2 = critical value for normal distribution at 95% confidence level, which is equal to 1.96 (Z value of alpha=0.05) or 5% level of significance (α=0.05) and a 5% margin of error (ω =0.05). The sample size was adjusted by adding 10% non-response rate and the final total sample size was 395 pregnant women.

Sampling Procedure and Technique

After considering both of the public health facilities of the town, the total sample size was proportionally allocated for each health facility based on their quarterly ANC flow. The total sample size after proportional allocation was 145 and 250 pregnant women, respectively, for hospital and health center. Then eligible pregnant women in each facility selected by using systematic random sampling techniques. The sampling interval or the Kth units (900/395 = 2) was obtained by dividing the numbers of mothers who visited ANC unit monthly by the sample size. The starting unit was selected by using the lottery method among the first Kth units.

Operational Definition

Knowledge: In this study, refers to knowledge of mothers about the risk factors, sign and symptoms, availability of treatment and preventive methods of obstetric fistula. Mothers were considered to have good knowledge of obstetric fistula if she correctly answered >50% of knowledge assessing questions [6].

Misconception: Refers to the incorrect response or opinion of the mothers regarding to the risk factors of obstetric fistula [24].

Data Collection Tools and Procedures

Structured interviewer administered questionnaire was used to collect the data, which was adapted from relevant literatures and modified to local context [24-27]. Questionnaires were first prepared in the English language, then it was translated first into Awigni by an individual who has good ability of these languages then retranslated back into the English languages to check its consistency. The questionnaire consisted of Socio-demographic characteristics, reproductive characteristics, and knowledge testing questions. Knowledge testing questions were assessed by +1 for correct answer and 0 for an incorrect answer. The score for each pregnant woman were summed and categorized.

Data Quality Assurance

Data was collected by trained data collectors and pre-testing of the instrument was done before the actual data collection. The questionnaire was pre-tested at 5% (20) pregnant women who attended ANC at Lideta health center with similar population. Data collectors and the supervisors trained for two days by the investigator. Necessary modifications and correction was done based on the results of the pre-test.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were entered into Epi data 3.5, and then exported to SPSS version 23.0 for analysis. During analysis, all explanatory variables which have significant association in bivariate analysis with a P value <0.20 was entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to get the AOR and those variables with 95% of CI and a P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant with knowledge and the misconception of obstetrics fistula. The multi collinearity test was done using variance inflation factor and there was no collinearity exists between the independent variables. The model goodness of the test was checked by using Hosmer- Lemeshow goodness of the fit test and the P-value of the model fitness of the test was greater than 0.5. Frequency tables, and descriptive summaries used to describe the study variables.

Socio Demographic Characteristics

A total of 395 women participated in the study with a response rate of 100%. The mean age of the mothers was 26.36 years with (±SD=4.95). Of these, 168 (42.5%) found in the age group of 20-25 years. Over 70.0% (n=280) of the women lived in urban and 114 (28.9%) had primary educational level (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age 15-19 20-25 26-30 31-35 36-40 |

23 (5.8) 168 (42.5) 136 (34.5) 42 (10.6) 26 (6.6) |

| Ethnicity Amhara Others* |

378 (95.7) 17 (4.3) |

| Residency Urban Rural |

280 (70.9) 115 (29.1) |

| Religion Orthodox Muslim Protestant |

333 (84.3) 52 (13.2) 10 (2.5) |

| Marital status Married |

395 (100.0) |

| Educational level Had not formal education Primary education Secondary school Diploma and above |

106 (26.8) 114 (28.9) 91 (23.0) 84 (21.3) |

| Occupational status House wife Merchants/self employed Employed |

247 (62.6) 91 (23.0) 57 (14.4) |

| Monthly income of the family in Ethiopian birr Low Medium High |

41 (10.4) 202 (51.1) 152 (38.5 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the women who attended ANC at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=395).

Knowledge and the Misconception of Obstetric Fistula

In this study, less than half (n=163, 41.3%) of pregnant mothers had heard of obstetric fistula, with most obtaining their information from health facility (n=80, 40.0%) and the others from media (n=65, 32.5%), school (n=32, 16.0%) and family/friends (n=23, 11.5%). Among 163 expectant pregnant mothers who had heard of obstetric fistula, 102 (62.6%), [95% CI= 54.6-69.9%] had good knowledge and 69 (42.3%), [95%: CI=35.0-49.7%] had the misconceptions of obstetric fistula.

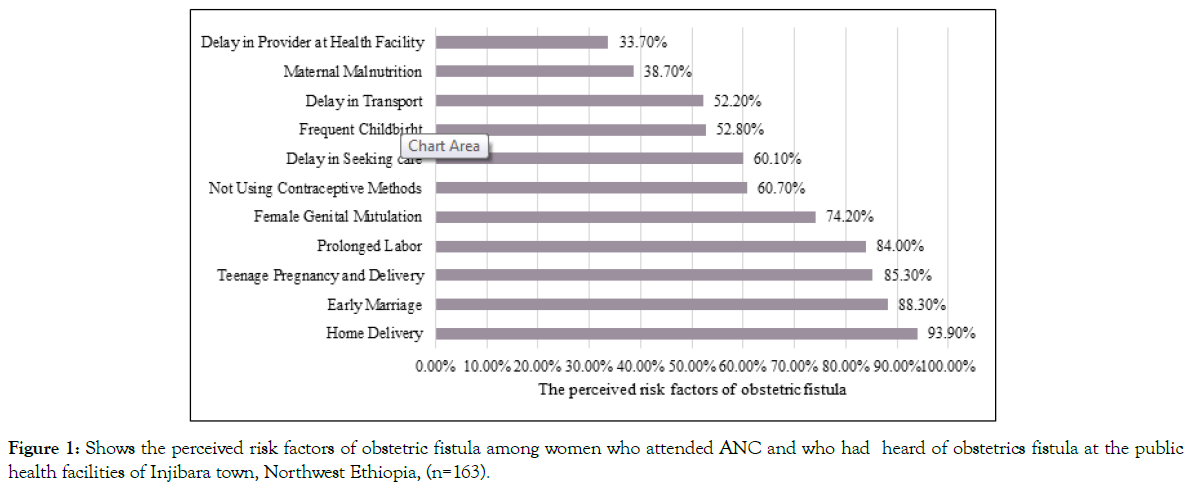

Among mothers who had heard of obstetrics fistula; home delivery (n=153, 93.9%), early marriage (n=144, 88.3%), teenage pregnancy and delivery (n=139, 85.3%) and prolonged labor (n=137, 84.0%) identified as risk factors of obstetric fistula (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Shows the perceived risk factors of obstetric fistula among women who attended ANC and who had heard of obstetrics fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=163).

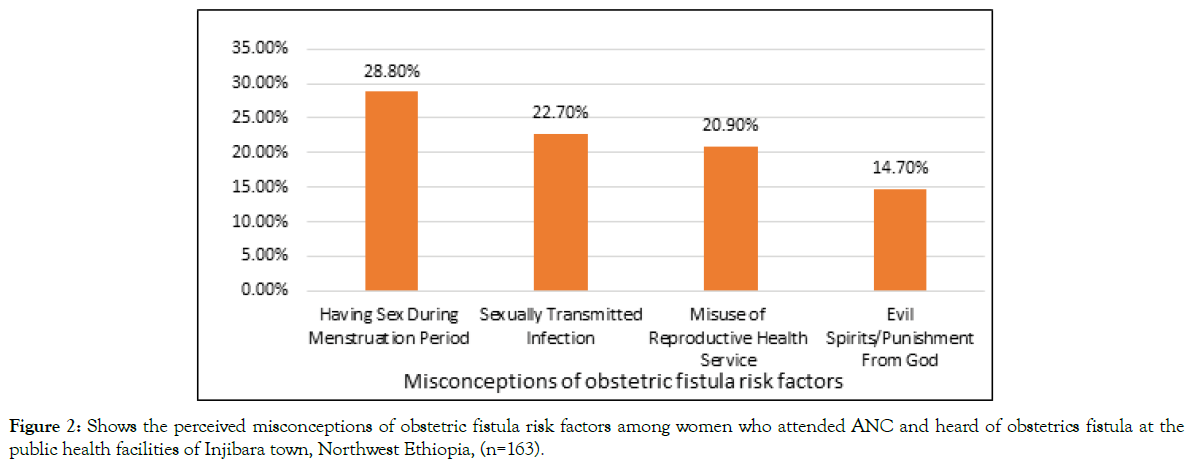

About 47 (28.8%) and 34 (20.9%) of the mothers responded that having sex during menstruation period and misuse of reproductive health service identified as the misconceptions of obstetric fistula risk factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Shows the perceived misconceptions of obstetric fistula risk factors among women who attended ANC and heard of obstetrics fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=163).

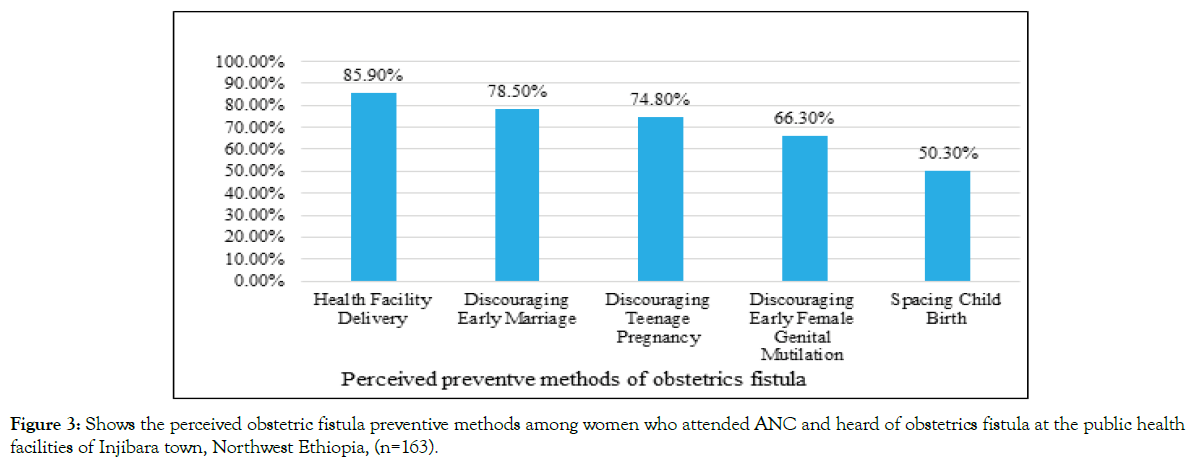

Of the 163 expectant women who had heard of obstetric fistula, 134 (82.2%), 70 (43.0%) and 47 (28.8%) women were mentioned urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence and vulvar irritation as a symptom of obstetric fistula respectively. The availability of obstetric fistula treatment knew by 92 (56.4%). About, (85.9%) (n=140) of the mothers believed that giving child birth at health institution with the assistance of health care professionals could prevent obstetric fistula (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Shows the perceived obstetric fistula preventive methods among women who attended ANC and heard of obstetrics fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=163).

Women who lived in rural were more likely to have both poor knowledge (62.5% vs 26.5%; P=0.001) and the misconception (60.0% vs 34.5%; P=0.002) about obstetric fistula compared with women who lived in urban. Having no educational background was associated with both poor knowledge (74.1% vs 30.1%; P=0.001) and the misconception (70.4% vs 36.8%; P=0.001) of obstetric fistula compared with women who had at least a primary educational level (Tables 2 and 3).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at first marriage <18 years ≥18 years |

70 (17.7) 325 (82.7) |

| Age at first pregnancy <18 years ≥18 years |

43 (10.9) 352 (89.1) |

| Parity Nulliparous Primiparous Multiparous |

152 (38.5) 88 (22.3) 155(39.2) |

| History of abortion Yes No |

83 (21.0) 312 (79.0) |

| History of ANC visit in previous pregnancy (n=243) Yes No |

158 (65.0) 85 (35.0) |

| Age at first childbirth (n=243) <18 ≥18 |

23 (9.5) 220 (90.5) |

| Place of delivery for the most recent childbirth (n=243) Health institution Home |

164 (67.5) 79 (32.5) |

| Mode of delivery for the most recent child birth (n=243) Spontaneous vaginal delivery Instrumental delivery Caesarean section |

178 (73.3) 39 (16.0) 26 (10.3) |

| Attendant of the labor (n=243) Health workers TBA Family |

164 (67.5) 43 (17.7) 36 (14.8) |

| History of PNC utilization (n=243) Yes No |

54 (22.2) 189 (77.8) |

| Utilization of contraceptive methods before the current pregnancy Yes No |

241 (61.0) 154 (39.0) |

| Numbers of ANC visits on the days of interview 1 2 3 4 |

164 (41.5) 116 (29.4) 65 (16.5) 50 (12.7) |

| Where you want to give birth in current pregnancy Health institution Home |

387 (98.0) 8 (2.0) |

| How you plan to travel to the health institution on the onsets of labor (n=387) Ambulance Taxi Foot Own car |

217 (56.1) 144 (37.2) 17 (4.4) 9 (2.3) |

| Types of facility Health center Hospital |

250 (63.3) 145 (36.7) |

Table 2: Reproductive and obstetric characteristics of the women who attended ANC at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=395).

| Variables | Poor knowledge (n=61) | Misconceptions (n=69) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) P –value | No. (%) P- value | |

| Age 15-19 20-25 26-30 >30 |

0.914 8 (42.1) 22 (39.3) 20 (36.4) 11 (33.3) |

0.982 8 (42.1) 23 (41.1) 23 (41.8) 15 (45.5) |

| Residency Rural Urban |

0.001 31 (62) 30 (26.5) |

0.002 30 (60.0) 39 (34.5) |

| Educational status No formal education Primary education Secondary and higher |

0.001 20 (74.1) 12 (33.3) 29 (29.0) |

0.001 19 (70.4) 19 (52.8) 31 (31.0) |

| Monthly income of the family Low Medium High |

0.001 15 (60.0) 28 (50.9) 18 (21.7) |

0.005 15 (60.0) 29 (52.7) 25 (30.1) |

| Age at first marriage < 18 years >18 years |

0.031 19 (52.8) 42 (33.1) |

0.771 16 (44.4) 53 (41.7) |

| Age at first pregnancy <18 years >18 years |

0.001 22 (66.7) 39 (30.0) |

0.232 17 (51.5) 52 (40.0) |

| Parity Nulliparous Primiparous Multiparous |

0.178 26 (47.3) 15 (31.9) 20 (32.8) |

0.727 23 (41.8) 18 (38.3) 28 (45.9) |

| Contraceptive method utilization No Yes |

0.001 30 (57.7) 31 (27.9) |

0.001 32 (61.5) 37 (33.3) |

| History of ANC visits No Yes |

0.001 16 (59.3) 19 (23.5) |

0.822 15 (55.6) 47 (58.0) |

| Place of delivery Home Health institution |

0.005 13 (56.5) 22 (25.9) |

0.295 12 (52.2) 34 (40.0) |

| PNC utilization No Yes |

0.319 25 (35.7) 10 (26.3) |

0.629 31 (67.4) 15 (32.6) |

| Types of health facility Health center Hospital |

0.011 44 (45.4) 17 (25.8) |

0.531 43 (44.3) 26 (39.4) |

Table 3: The relationship between poor knowledge or the misconception of obstetric fistula with socio-demographic and obstetric characteristic among ANC attendees and who had heard of obstetric fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=130).

Factors Associated with Knowledge of Obstetric Fistula

In bivariate analysis; age of the mothers, residency, educational level of the mothers, monthly income of the family, age at first marriage and pregnancy, parity, utilization of contraceptive methods, history of ANC visits in previous pregnancy, place of delivery, and utilization of PNC were significantly associated with knowledge of obstetric fistula at a P value of <0.20. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis; residency, educational level of the mothers, monthly income of the family, age at first pregnancy, parity, utilization of contraceptive methods, history of ANC visits, and place of delivery remained significantly associated with knowledge of obstetric fistula.

There was an increasing trend toward knowledge of obstetric fistula as increasing educational levels, nearly four times being had primary education level [AOR=3.99, 95% CI=1.10-14.46] and 5.24 times being attending secondary and higher education [AOR=5.24, 95% CI=1.61-17.01] than not having a formal education (Table 4).

| Variables | Knowledge of obstetric fistula | COR (95%-CI) | AOR (95%-CI) | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||||

| Age** 15-19 20-25 26-30 >=31 |

11 34 35 22 |

8 22 20 11 |

1 1.12 (0.39-3.23) 1.27 (0.44-3.69) 1.45 (0.45.4.65) |

1 0.69 (0.17-2.79) 0.99 (0.21-4.71) 1.36 (0.22-8.39) |

0.602 0.997 0.740 |

| Residency** Rural Urban |

19 83 |

31 30 |

1 4.51 (2.22-9.16) |

1 3.19 (1.33-7.67) |

0.009* |

| Educational level** No-formal education Primary education Secondary and above |

7 24 71 |

20 12 29 |

1 5.70 (1.89- 17.25) 7.00 (2.67-18.32) |

1 3.99 (1.10- 14.46) 5.24 (1.61-17.01) |

0.035* 0.006* |

| Monthly income** Low Medium High |

10 27 65 |

15 28 18 |

1 1.45 (0.55-3.77) 5.42 (2.08-14.08) |

1 2.20 (0.62-7.85) 3.88 (1.11-13.55) |

0.222 0.034* |

| Age at first marriage** <18 years >18 years |

17 85 |

19 42 |

1 2.26 (1.07-4.80) |

1 1.47 (0.46-4.70) |

0.514 |

| Parity** Nulliparous Primiparous Multiparous |

29 32 41 |

26 15 20 |

1 1.91 (0.85-4.30) 1.84(0.86-3.90) |

1 3.05 (1.08-8.60) 4.05 (1.45-11.28) |

0.036* 0.007* |

| Age at first pregnancy** <18 years >18 years |

11 91 |

22 39 |

1 4.67 (2.06-10.54) |

1 3.38 (1.20-9.57) |

0.021* |

| Contraceptive methods utilization** No Yes |

22 80 |

30 31 |

1 3.52 (1.77-7.01) |

1 3.20 (1.38-7.44) |

0.007* |

| History of ANC visit*** No Yes |

11 62 |

16 19 |

1 4.75 (1.88-11.96) |

1 4.05 (1.56-10.51) |

0.004* |

| PNC utilization*** No Yes |

45 28 |

25 10 |

1 1.55 (0.65-3.72) |

1 1.08 (0.41-2.84) |

0.874 |

| Place of delivery*** Home Health institution |

10 63 |

13 22 |

1 1.47 (0.48-4.52) |

1 2.97 (1.08-8.17) |

0.035* |

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis of the knowledge of obstetric fistula among ANC attendees and who had heard of obstetric fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=163).

Factors Associated with the Misconception of Obstetric Fistula

In bivariate analysis; residency, educational level of the mothers, monthly income of the family, utilization of FP methods and knowledge of obstetrics fistula were significantly associated with misconception of obstetrics fistula at a P value of <0.20. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis; residency, educational level of the mothers and utilization of FP methods remained significantly associated with misconception of obstetrics fistula. Mothers who are lives in rural were 2.46 times more likely had misconception of obstetrics fistula relatives to mothers who are lives in urban [AOR=2.46, 95% CI=1.17-5.15] (Table 5).

| Variables | Misconception of obstetric fistula | COR (95%-CI) | AOR (95%-CI) | P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Residency Rural Urban |

19 38 |

31 75 |

3.22 (1.61-6.43) 1 |

2.46 (1.17-5.15) 1 |

0.017* |

| Educational level No-formal education Primary education Secondary and above |

18 19 32 |

8 18 68 |

4.78 (1.88- 12.15) 2.24 (1.04-4.84) 1 |

4.01 (1.51-10.65) 2.07 (0.92- 4.66) 1 |

0.005* 0.079 |

| Monthly income Low Medium High |

15 29 25 |

10 26 58 |

3.48 (1.37-8.80) 2.59 (1.28-5.25) 1 |

2.51 (0.91-6.96) 1.69 (0.77-3.70) 1 |

0.077 0.192 |

| Contraceptive methods utilization No Yes |

32 37 |

20 74 |

3.20 (1.61-6.34) 1 |

2.55 (1.23-5.29) 1 |

0.012* |

| Knowledge of obstetrics fistula Poor knowledge Good knowledge |

31 38 |

30 64 |

1.74 (0.91-3.31) 1 |

0.70 (0.31-1.58) 1 |

0.392 |

Table 5: Logistic regression analysis of the misconceptions of obstetric fistula among ANC attendees and who had heard of obstetric fistula at the public health facilities of Injibara town, Northwest Ethiopia, (n=163).

In this study, less than half of women had heard of obstetric fistula. Among women who had heard of obstetric fistula, 62.6% (95% CI= 54.6-69.9%) had good knowledge obstetric fistula and, 42.3% (95%: CI=35.0-49.7%) of the women were having misconceptions of it. This finding is in line with a study done in Ghana 62.8% [24]. However, the result in this study is higher than study done in Burkina Faso 36.4% [6]. The difference might be attributed to the age of participants, as the study conducted in Burkina Faso were conducted on young women, while this study was conducted by including all reproductive age group pregnant women and majority of them were had history of previous pregnancy, thus may have accounted for higher knowledge of obstetric fistula in our study.

The knowledge of obstetric fistula in this study is higher than a study done in Nigeria shows that 29.5% and 4.7% of had moderate and high knowledge of vesico vaginal fistula (VVF) respectively, while the majority of the women with VVF had low knowledge [27]. This gap might be attributed to the educational levels of the women, as seen in this study, around 73% of the women had at least primary educational level, while in the study done in Nigeria, and around 36% had no formal education. Moreover, in this study, 67.5% of the women were gave birth at the health institution in their previous pregnancy, while the study done in Nigeria shows that 77.1% were gave birth at home [27]. This shows that having at least primary education level and utilizing maternal health services have a positive effect on knowledge of obstetric fistula.

However, the finding in this study is lower than another study done in Nigeria, shows that 70% of women with fistula on admission had knowledge of the causes of their fistula [28]. This difference might be due to the study participants, as this study includes only pregnant women without fistula, while the study done in Nigeria were includes women with obstetric fistula.

Among ANC attendees and who had heard of obstetric fistula, the majority of the mothers were perceived that: home delivery, prolonged labor and teenage pregnancy as risk factors of obstetric fistula. This finding is consistent with studies done in different countries [7,21,24-28]. Nearly 83% of the mothers were mentioned at least one symptom of obstetric fistula. This finding is higher than studies reported in rural parts of Ethiopia [27,29]. This difference might be time gap and residency, as those studies was conducted in rural parts of the country, while this study was conducted by include both urban and rural residential with the majority of urban residences. The majority of the women were believed that giving childbirth at health institution could prevent obstetric fistula. This finding is supported by studies done in Ghana and Nigeria [24,27].

Among women who were mentioned the risk factors of obstetric fistula, 42.3% had misconceptions about it and they perceived that: evil spirits, having sex during menstruation periods, sexually transmitted disease, and misuse of reproductive health services as risk factors of obstetric fistula. Similar findings have been reported in studies done in different countries [21,24,26]. Having these misconceptions may have a negative effect on the use of reproductive health services, it also makes them not be able to take practical steps in its prevention. The availability of obstetric fistula treatment was known by 56.4% of clinic attendees. Similar finding, reported in Ghana [24].

Less than half (40.0%) of the women who had heard of obstetric fistula, obtained their information from a health facility. Similar finding, reported in Ghana [24]. While the remaining 60.0% of the women who were aware of obstetric fistula got the information through the media, school and family/friends. Similar finding, reported in Burkina Faso [6]. This indicates that counselling on obstetric fistula may not have been an integral components ANC in the health facilities and as well as the information obtained from healthcare providers or other source may not have been very accurate as seen in this study 42.3% of the mothers had misconceptions of obstetric fistula.

Women who lived in urban were 3.19 times more likely had good knowledge of obstetric fistula. This finding agrees with a study done in Burkina Faso [6]. This may be due to the availability of information accessed between rural and urban residency as participants who lived in urbanized area has more information access.

Women who had primary educational level were nearly four times and women who had secondary and higher educational level were 5.24 times more likely had good knowledge of obstetric fistula. The finding in this study agrees with a study done in the Bench Sheko Zone [30]. It is also in line with studies conducted in different countries [6,24,27,31,32]. This indicates that attending education, even primary educational level is a cornerstone to increasing the knowledge of women towards obstetric fistula [33].

Women who had high monthly family income were 3.38 times more likely had the odds of having good knowledge of obstetric fistula. This may attribute that women who had high monthly family income could have a high chance of influence on their overall empowerment and access to information. This finding is supported by a study done in Ghana shows that women in employment are more likely to seek ANC services as they are less likely to face financial barriers [24]. Being pregnant for the first time after the age of eighteen were increased the odds of having good knowledge of obstetric fistula 3.38 times. The possible reason may be due to their residency and educational status as seen in this study, more than half of women who were being pregnant for the first time after the age of eighteen where lives in urban and educated, because of these, they may have a chance of acquiring knowledge on the risk of being pregnant before the age of eighteen.

Having good knowledge of obstetric fistula was increased with parity, threefold being primiparous and fourfold being multiparous. The finding agrees with studies done in Burkina Faso and Ghana [6,24]. The possible reason may be that women who have history of previous pregnancy may had history of maternal and child health care services utilization, thus may intern increasing their chance of getting more information about obstetric fistula in the form of health education or counselling. Having history of contraceptive methods utilization were increasing the chance of having good knowledge of obstetric fistula by 3.20 times. This finding is supported by a study conducted in Nigeria [32]. This indicates that utilizing maternal health care services may increase the chance of acquiring information related to the maternal health.

Among mothers who had history of previous child birth and those who had heard of obstetric fistula: having history of ANC visits and childbirth at health institution was increased the odds of having good knowledge of obstetric fistula four times and nearly three times respectively. This finding is in line with a study conducted in the Bench Sheko Zone [30]. Women who are not utilized maternal health care services have low knowledge of obstetric fistula and they are at risk for developing obstetric fistula [27]. Utilization of maternal health services is the most favourable contact point for mothers to get health related information from health providers.

Living in rural were increased the chance of having the misconception of obstetric fistula by 2.46 times. This may attributed to that woman who lives in rural may have less chance of getting information about obstetric fistula. This finding supported by a study conducted in Burkina Faso [6]. Mothers who have no formal education were 4.01 times more likely had misconceptions of obstetric fistula. The possible reason might be that those women who have no formal education may have less chance of getting information related to maternal health. Mothers who have at least primary educational levels may have high chance of getting information about maternal health issue [6,24,27,31,32]. Mothers who have no history of contraceptive utilization were 2.55 times more likely had misconception of obstetric fistula. The possible reason might be utilizing health care service provided by the health care professionals, may increase the mother’s level of information regarding to their health. Women who used maternal health care were more likely had information of obstetric fistula [32].

Pregnant women who have no ANC visits were not addressed.

Less than half of the mothers had heard about obstetric fistula, among them who had good knowledge of obstetric fistula was low, while the misconceptions of obstetric fistula were high. Sociodemographic, reproductive and obstetric related factors were significantly associated with knowledge of obstetric fistula as well as the misconception of it. Therefore, this study indicates that there is a need to give more emphasis for educating women about obstetric fistula, its risk factors and prevention methods by integrating it into the components of ANC.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences and a formal letter, from Injibara town health office and concerned bodies. A written consent was obtained from each study participants for those ages greater than 16 years and from parents/ guardians for those ages less than 16 years.

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

WF, AZ, and FY: conception of the research idea, study design, data collection, and supervision. WF, FA, TW and EA: data analysis, interpretation and manuscript write-up. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was financially supported by Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Sciences. The funder has no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Firstly, we would like to thank Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Secondly, we would like to thank the Injibara town health office and health facilities staffs for giving necessary information. Finally, we would like to acknowledge, the study participants, data collectors and supervisors for their participation in this study.

Citation: Feyisa W (2021) Factors Associated With Knowledge and the Misconception of Obstetric Fistula in Northwest Ethiopia. J Women's Health Care 10:556. doi: 10.35248/2167-0420.21.10.556

Received: 02-Oct-2021 Accepted: 18-Oct-2021 Published: 25-Oct-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2167-0420.21.10.556

Copyright: © 2021 Feyisa W, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.