Journal of Antivirals & Antiretrovirals

Open Access

ISSN: 1948-5964

ISSN: 1948-5964

Research Article - (2022)Volume 14, Issue 2

Background: Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) remains a serious health problem despite the prevention and treatment measures currently implemented. There is little data on the molecular characterization of the strains circulating in the Central African Republic (CAR). Here, we sequenced the full-length genome of HBV isolated from CAR patients.

Methodology: The serum samples were collected at the Institut Pasteur de Bangui. The full-length viral genome was isolated and sequenced using the Sanger technique with four overlapping primers. Sequences were analyzed in silico for mutations and drug resistance using bioinformatics tools.

Results: Four full-length HBV genomes were successfully sequences. All four isolates belonged to genotype E and contained an rtI90L mutation in the Reverse Transcriptase (RT) functional domain A. One isolate harbored a nonsense mutation at the 3' end of the S-ORF leading to a premature stop codon and the production of short protein sequences for all three surface proteins (large, middle, and small surface antigens). In silico analysis showed that this same mutant isolate also carried an rtH234N mutation in the RT functional domain D which increases the binding energy and leads to reduced affinities for adefovir and tenofovir.

Conclusions: Hepatitis B genotype E is the major genotype circulating in the CAR. We identified a mutation in the RT gene of a CAR HBV strain and this mutation may be associated with drug resistance. Therefore, there is a need for further, in-depth investigation of HBV RT in the HBV strains in circulation in the CAR.

Hepatitis B virus; Central African Republic; Complete genome sequence; Mutation; Binding energy

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is an enveloped DNA virus that infects the liver, causing inflammation and hepatocellular necrosis [1]. Based on a nucleotide divergence of more than 8% in the entire genome sequence, HBV is categorized into 10 genotypes, from A to J [2]. The HBV genotypes can be further classified into sub genotypes with 4%-8% genomic variability. The HBV genotypes have a distinct geographical distribution worldwide and genotypes A, D and E are the major HBV genotypes in circulation that have been identified in Africa, with genotype E being dominant in West and Central Africa [3-5].

The HBV genome consists of a ~3200 bp, circular and partially double-stranded DNA molecule that encodes four genes: the preS1/preS2/S gene encoding the hepatitis envelope proteins L, M and S; the pre C/C gene, which encodes the precore and structural capsid-forming core protein; the P gene encoding the Reverse Transcriptase (RT) and other proteins required for replication; and the X gene associated with the development of liver cancer, although it is not fully understood [6,7].

Despite the prevention, diagnosis, and control measures currently implemented, HBV remains one of the most devastating infectious diseases in the world, with over 800,000 deaths annually [8].Alongside the in vitro and in vivo experiments to combat the disease, the generation of molecular data and in silico experiments are of considerable interest, because they contribute to the understanding of genotypes and can help address issues involving prevention, diagnosis, and control strategies.

The HBV polymerase governing RT activity is of considerable interest for in silico drug design, drug assessment and drug resistance analyses. Recently, much of the crystal structure of HBV RT has been deduced from a human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase (HIV-1 RT) using homology modeling [9,10].

The present study combined wet and dry laboratory experiments to compile molecular data and assess binding affinities of some selected nucleoside/nucleotide analogues (NAs) on HBV isolates from the CAR.

Study site and sample collection

Serum samples were collected at Institut Pasteur de Bangui (IPB) in the Central African Republic, a landlocked country in Central Africa. The samples included samples archived in the year 2018 and samples prospectively collected in 2019 at the IPB Viral Hepatitis Laboratory (Table 1). None of the patients had been vaccinated and had no treatment histories recorded at IPB; they were considered treatment-naive patients. They all tested positive for the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), confirmed, and were screened for the hepatitis e-antigen (HBeAg) at the IPB Serological Laboratory. Samples were stored at -20oC before the study. All patients in this study came to IPB for HBV screening; patient consent was obtained by IPB.

| Sample ID | Gender | Age | Collection year | GenBank acc. no |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR_39 | M | 37 | 2019 | MN967526 |

| CAR_59 | M | 39 | 2018 | MN967527 |

| CAR_78 | F | 24 | 2019 | MN967528 |

| CAR_93 | M | 32 | 2019 | MN967529 |

Table 1: General information for the successfully sequenced HBV samples.

Viral DNA extraction and amplification of the HBV complete genome

Total DNA was extracted from 200 μl of HBV-positive serum using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (catalog number 51306, Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The full-length genome of HBV was amplified using the specific primers WA-L and WA-R as described previously [11]. Briefly, the PCR mix was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl containing 0.1 pmol of each primer, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 250 μM of each dNTP, 10 mM of Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), 30 mM of KCl, 1.5 mM of MgCl2, stabilizer and tracking dye and 0.8-2 ng/μl of DNA template. The PCR conditions were set with initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 3 min 30 s, and a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min.

Amplification of nucleotides spanning positions 1750 to 2500

The primers WA-L and WA-R flank the nucleotide positions 1804 to 1859 (the linearization of the HBV genome occurs in this region). Then, the amplification of the region spanning nucleotide positions 1750 to 2500 was carried out using either the AL1-L and AL1-R primer pair [11], or the newly designed primers HBVgapFwd (5’-CTGCAATGTCAACGACCGAC-3’) and HBVgapRv (5’-GATATTCATTTGCACCAGGACA-3’) based on the raw extracted viral DNA as the template. A ProFlex PCR Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems) was used for thermal cycling as follows: 95ºC for 5 min and then 30 cycles consisting of 95ºC for 30 s, 55ºC for 1 min, and 72ºC for 1 min 30 s, with a final elongation at 72ºC for 10 min.

PCR product purification and sequencing

All PCR products were resolved on 1% agarose gels stained with GelRed (Biotium) and viewed using a UV transilluminator. Sanger sequencing was performed by Macrogen (the Netherlands); the PCR product of the full-length genome was sequenced using three pairs of overlapping primers A2-L/A2-R, A3-L/A3-R and A4-L/ A4-R as described previously [11] to generate sequences covering nucleotides 1 to 1750 and 2500 to 3212 of the HBV genome.

The PCR products generated by the primer pairs AL1-L/AL1-R or HBVgapFwd/HBVgapRv were sequenced using the same primers.

Sequence clean-up and assembly

All the forward and reverse sequences obtained from Sanger sequencing were cleaned and assembled using CLC Genomic Workbench 8.0.3, then submitted to a NCBI nucleotide BLAST for a homology search.

Sequence genotyping, serotyping and recombination analysis

Genotype determination was carried out using the NCBI genotyping tool on the obtained full-length genomes. Further, phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA X using the neighbor-joining clustering method. To check for recombination, sequences were submitted to the recombination tool of NCBI.

Mutation and ORFs analyses

Mutations were analyzed in the complete genome using Geno2pheno.hbv and BioEdit. The HBV genotype E (acc. Number AB091255) obtained from the HBV database was used as a reference. Nucleotide sequences were analyzed online using the NCBI ORF finder.

Homology modeling of the mutant rtH234N

The nucleotide sequence of the polymerase gene was translated to the protein sequence online using the translation tool ExPASy (https://web.expasy.org/translate/) from the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB). The conserved domain was identified in NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) and homology model of the HBV reverse transcriptase (HBVrt) was built in MODELLER 9v8 [12] using the crystal structure of HIV- 1 RT (PDB code: 1T05) as a template. A total of 10 models were generated and the model with the lowest Discrete Optimization Protein Energy (DOPE) considered as the best native structure [13] was selected.

To generate the control model, the mutated amino acid sequence was substituted with the correct sequence based on the reference sequence (GenBank AB091255). To generate the tertiary structure of the proteins, the coordinates of the template-primer DNA duplex, the two Mg2+ cations and one Tenofovir (TNV) ligand were transferred from the template structure to the modeled proteins.

Modeled protein structure assessment

The quality of the protein structure was evaluated using PROCHECK [14] and PRoSA-web [15] and the selected structures were visualized using the PyMOL-2.3.2 molecular viewer [16].

Molecular docking of the mutant rtH234N with adefovir and tenofovir

Molecular docking of the modeled proteins was carried out using the AutoDock Vina docking engine version 1.5.6 [17]. Polar hydrogen molecules were added to the receptor with AutoDock and the adefovir and tenofovir ligands were downloaded from the PubChem server [18]. A grid box (center x=65.492, y=59.681, z=-52.597 and size x=44, y=60 z=56) was generated at the region containing the binding site in the protein by referring to the HIV- 1 RT model ligand. The best binding pose was identified based on the lowest binding free energy. The docking output files were visualized in PyMol molecular viewer and LigPlot [19].

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Scientific Committee of the University of Bangui, CAR, Ref. No: 21/UB/FACSS/ CSVPRS/19.

PCR and sequencing

Following PCR and amplicon sequencing, a full-length sequence of HBV was obtained for four samples. Overlapping sequences were analyzed in CLC genomic workbench vers. 8 to generate complete genome sequences. The nucleotide sequences of the complete HBV genome (3212 bp) reported in this study have been submitted to GenBank (NCBI) and assigned the accession numbers [MN967526- MN967529] (Table 1).

Genotyping and recombination analyses

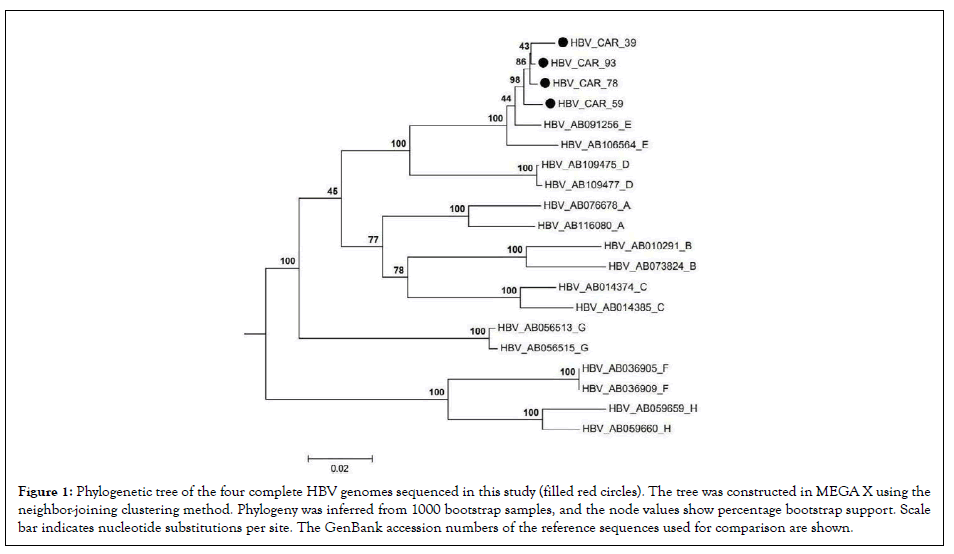

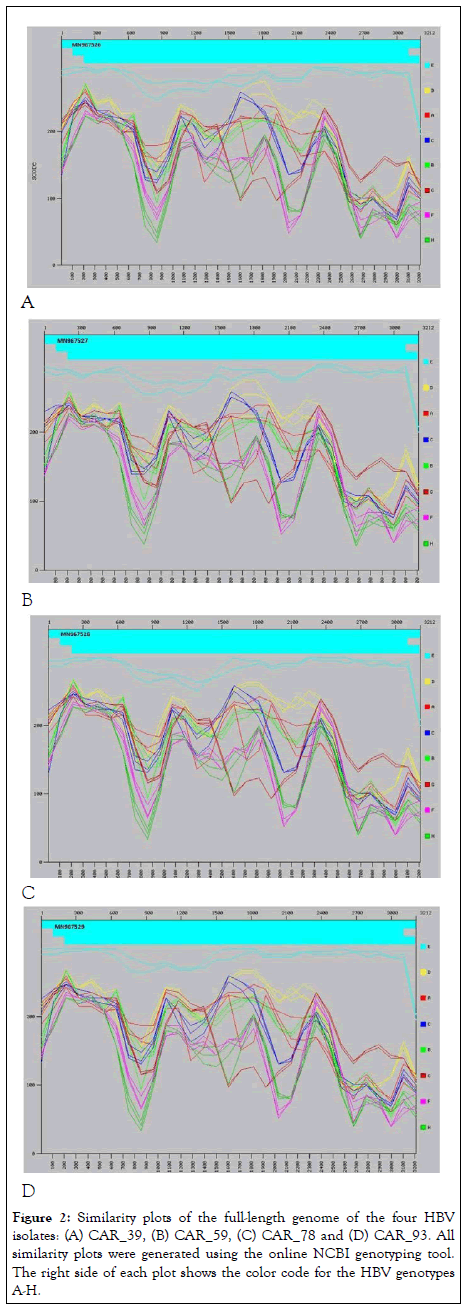

The phylogenetic tree (Figure 1)and NCBI genotyping tool revealed that all the four sequenced isolates belong to genotype E. The recombination analysis did not show evidence of recombination; however, the similarity plot (Figure 2) showed high similarity with genotype D in the region covering nucleotides 1500 to 1800.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic tree of the four complete HBV genomes sequenced in this study (filled red circles). The tree was constructed in MEGA X using the neighbor-joining clustering method. Phylogeny was inferred from 1000 bootstrap samples, and the node values show percentage bootstrap support. Scale bar indicates nucleotide substitutions per site. The GenBank accession numbers of the reference sequences used for comparison are shown.

Figure 2: Similarity plots of the full-length genome of the four HBV isolates: (A) CAR_39, (B) CAR_59, (C) CAR_78 and (D) CAR_93. All similarity plots were generated using the online NCBI genotyping tool. The right side of each plot shows the color code for the HBV genotypes A-H.

Open reading frame and mutation analyses

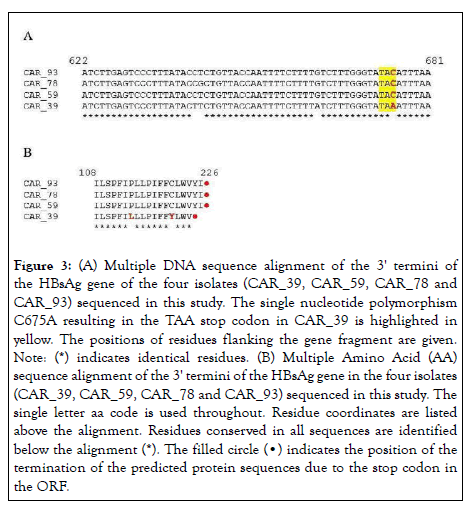

The HBsAg Open Reading Frame (ORF) predicted to encode a protein of 226 Amino Acids (AA) was analyzed using the NCBI ORF finder. The results revealed that the HBV CAR_39 isolate contains a C675A mutation at the 3' end of the HBsAg ORF (Figure 3A). A comparison of the predicted protein sequences of the HBsAg gene from the four sequenced HBV isolates showed that this single nucleotide variation introduces an internal TAA stop codon, resulting in a premature termination of translation, with the loss of the last two aa, YI, leading to a truncated HBsAg variant of 224 aa long (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: (A) Multiple DNA sequence alignment of the 3' termini of

the HBsAg gene of the four isolates (CAR_39, CAR_59, CAR_78 and

CAR_93) sequenced in this study. The single nucleotide polymorphism

C675A resulting in the TAA stop codon in CAR_39 is highlighted in

yellow. The positions of residues flanking the gene fragment are given.

Note: (*) indicates identical residues. (B) Multiple Amino Acid (AA)

sequence alignment of the 3' termini of the HBsAg gene in the four isolates

(CAR_39, CAR_59, CAR_78 and CAR_93) sequenced in this study. The

single letter aa code is used throughout. Residue coordinates are listed

above the alignment. Residues conserved in all sequences are identified

below the alignment (*). The filled circle (•) indicates the position of the

termination of the predicted protein sequences due to the stop codon in

the ORF.

In silico prediction of HBV RT three-dimensional structure and molecular docking simulation

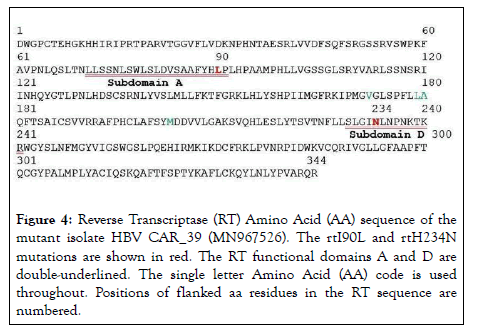

The mutations identified included rtH234N and rtI90L harbored in the polymerase gene of the HBV CAR_39 isolate (Figure 4). Ramachandran plots results show that 85%-86% of the residues were found in the most favored region, 10%-11% in the additional allowed region, and 2% in the generously allowed region. The overall Z scores were -3.36 and -4.1 for the wild type and rtH234N mutant, respectively.

Figure 4: Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Amino Acid (AA) sequence of the mutant isolate HBV CAR_39 (MN967526). The rtI90L and rtH234N mutations are shown in red. The RT functional domains A and D are double-underlined. The single letter Amino Acid (AA) code is used throughout. Positions of flanked aa residues in the RT sequence are numbered.

To predict the development of resistance in mutant virus strains, we examined the binding energy of therapeutic agents with HBV target molecules. Here, the binding energy of the commonly used anti-HBV agents the Nucleoside/Nucleotide Analogues (NAs) adefovir and tenofovir with RT from the HBV CAR_39 (MN967526) mutant was calculated and compared with that of the wild-type RT (AB091255). The rtH234N mutation increased the binding energy by 1 and 0.8 kcal/mol for adefovir and tenofovir, respectively (Table 2).

| HBV RT type | Adefovir | Tenofovir | GenBank acc. no |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type rtH234 | -7.9 | -7.9 | AB091255 |

| Mutant rtH234N | -6.9 | -7.1 | MN967526 |

| Mutant rtH234N+rtI90L | -9.8 | -6.8 | MN967526 |

Table 2: Binding energy (kcal/mol) of HBV Reverse Transcriptase (RT) mutants to adefovir and tenofovir.

This increase suggests that the rtH234N mutation limits the binding of the drugs, potentially promoting the resistance of HBV CAR_39 to adefovir and tenofovir. The double RT mutation at rtH234N + rtI90L elevated the binding energy for tenofovir by 1.1 kcal/mol compared with the wild type. In contrast, these double mutations induced a significant decrease in binding energy of 1.9 for adefovir (Table 2), suggesting that a concurrent mutation at rtH234N and rtI90L improves adefovir binding affinity for HBV RT.

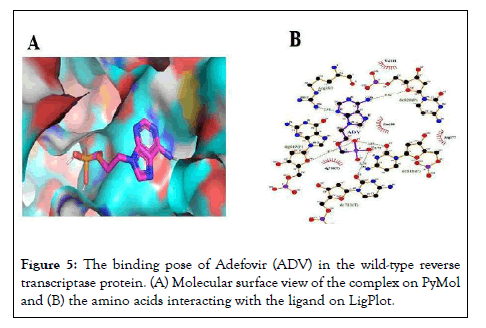

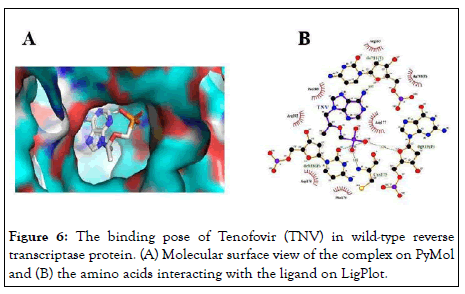

The best poses (Figures 5A and 6A) showed the best binding affinities (-7.9 kcal/mol) of adefovir and tenofovir for the wild-type model and were quite similar to the rtH234N mutant model but differed in their binding residues (Figures 5B and 6B) (arginine 183 for adefovir and cysteine 175 for tenofovir) (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: The binding pose of Adefovir (ADV) in the wild-type reverse transcriptase protein. (A) Molecular surface view of the complex on PyMol and (B) the amino acids interacting with the ligand on LigPlot.

Figure 6: The binding pose of Tenofovir (TNV) in wild-type reverse transcriptase protein. (A) Molecular surface view of the complex on PyMol and (B) the amino acids interacting with the ligand on LigPlot.

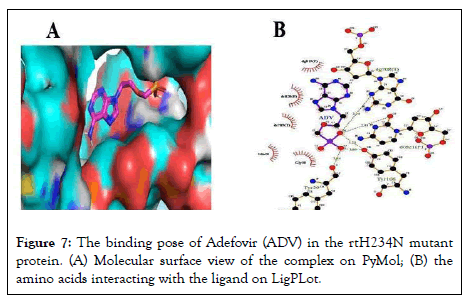

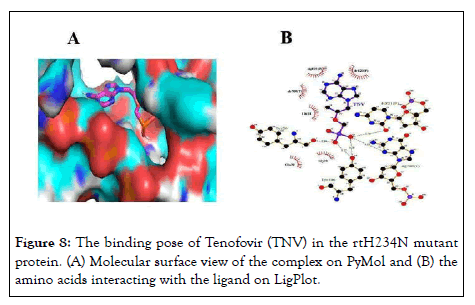

In the wild-type model, the two NAs had different binding residues, but had the same best binding affinity of -7.9 kcal/mol. For the rtH234N mutant, both NAs had the same binding residues, i.e. tyrosine 29 and tyrosine 106, but differed in their binding energies (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7: The binding pose of Adefovir (ADV) in the rtH234N mutant protein. (A) Molecular surface view of the complex on PyMol; (B) the amino acids interacting with the ligand on LigPLot.

Figure 8: The binding pose of Tenofovir (TNV) in the rtH234N mutant protein. (A) Molecular surface view of the complex on PyMol and (B) the amino acids interacting with the ligand on LigPlot.

HBV infection remains a serious public health problem. There is therefore an urgent need for detailed analyses to improve our understanding of the structure, genetic sequence, and diversity of HBV. Increasing our understanding of virus genetics in various endemic regions can contribute to better management of patients and the development of improved diagnosis, prevention and control strategies including new approaches to monitoring the infection [20].

The present study generated the full-length genome sequence of four HBV isolates using Sanger sequencing technology. All four ORFs were identified and the seven deduced proteins were deposited in the GenBank database.

Although the Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) platforms are rapidly becoming more widely used for virus genome sequencing [21-23], Sanger sequencing, which consists of consensus sequences of overlapping short fragments of viral genes, is still a highly useful approach.

Among the three HBV genotypes (A, E, and D) circulating in the CAR, HBV/E remains the dominant genotype [3,5,24]. Although all the HBV sequences generated in this study belonged to genotype E, the nucleotide BLAST plots showed high similarity with genotype D for nucleotides 1700-1900, a region that includes recombination breakpoints described in a previous study [21].

Alignment of the full-length sequences revealed several mutations, including an isolate (HBV CAR_39) harboring a stop codon detected at the 3' end of the surface protein. Because the three surface proteins (large, middle, and small) are all produced by the same S-ORF, (spanning nucleotides join (2848..3212,1..835),join (3202..3212,1..835), and 155..835, respectively for large, middle, and HbsAg), they all have the same 3' end. Therefore, the presence of a stop codon at the 3' end of the S-ORF would affect the production of all three surface proteins. Figure 3 shows how the detected stop codon reduces the HBsAg by 2 aa, which may interfere with the detection of HBsAg, an antigen of great importance for diagnosis and prevention measures.

The present study detected several mutations in the HBV genome of analyzed isolates, however little information was available on mutation rtH234N, requiring an assessment.

Due to its functions, HBV DNA polymerase is an important drug target for the treatment of HBV infections [25]. Therefore, mutations in HBV may reduce the success of existing treatments. The HBV DNA polymerase has four domains, thereby allowing multifunctional proteins. The domains include a priming region, a spacer region with unknown function, a catalytic region with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase/DNA polymerase activity, and a carboxy-terminal region with ribonuclease H activity [26]. To date, the crystal structure of HBV polymerase is unknown, because much of its structure has been deduced from HIV-1 RT using homology modeling [9-10]. Even with differences in aa sequences and in domain structure, almost all polymerases appear to have a common right-handed configuration with a thumb, a palm, and a finger domain. The palm domain contains the active site and catalyzes the phosphoryl transfer reaction; the finger domain can facilitate interactions with the incoming dNTPs as well as the template base to which it is paired; and the thumb is a domain that may play a role in positioning the duplex DNA, processivity, and translocation [27]. The palm located in the subdomain adjacent to the 3' terminus of the primer strand is the binding site of NAs and dNTPs.

Mutation rtN236T has previously been identified to be associated with adefovir resistance and reduction of tenofovir susceptibility [28]. Consequently, the rtH234N mutation (at 2 aa away from N236) harbored in isolate MN967526 was selected for assessment of affinity for adefovir and tenofovir. Docking of adefovir and tenofovir showed nearly similar affinities and the same binding residues (tyrosine 29 and tyrosine 106) in the mutant. However, in the wild type, adefovir has Arg183 as its ligand and tenofovir has Cys175 with no difference in binding energy. The docking analysis also revealed an increase in the binding energy of up to 1 kcal/mol with the mutant protein compared with the wild type, suggesting a potential development of drug resistance in the CAR_39 isolate [29]. Further study needs to be conducted to confirm the in silico results of the present study.

The HBV genotype E is predominant in the CAR. The present study generated four complete genome sequences of the HBV/E circulating in the CAR which were analyzed resulting in the detection of a premature stop codon harbored by the 3’ end of one HBV isolate. An in silico affinity analysis predicts a decrease in affinity for adefovir and tenofovir for one isolate due to the rtH234N mutation. We therefore recommend an in-depth investigation on HBsAg of HBV isolates from CAR.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This work comprises, in part, Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda’s master thesis, performed in part at the Viral Hepatitis Laboratory at the Institut Pasteur de Bangui and the BecA-ILRI Hub.

HBV serological tests were carried out by the Serology Laboratory at the Institut Pasteur de Bangui.

This research was supported by the Pan-African University of the African Union Commission for Science and Technology. Partial funding was also received from the Japan International Corporation Agency (JICA) through the AFRICA-ai-JAPAN PROJECT and the BecA-ILRI Hub program through the Africa Biosciences Challenge Fund (ABCF) program. The ABCF program is funded by the Australian Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) through the BecA-CSIRO partnership, the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), the UK Department for International Development (DFID), and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Conceptualization

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda and revised by Juliette Rose Ongus, Rosaline Macharia, Narcisse Patrice Komas, and Roger Pelle.

Data collection

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda, guided by Narcisse Patrice Komas.

Benches’ work

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda and Eunice Machuka.

Supervision

Rosaline Macharia, Juliette Rose Ongus, Narcisse Patrice Komas, and Roger Pelle.

Data analyses

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda, Rosaline Macharia, Eunice Machuka, and Roger Pelle.

Writing-original draft

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda

Writing, reviewing and editing

Giscard Wilfried Koyaweda, Juliette Rose Ongus, Rosaline Macharia, Eunice Machuka, Narcisse Patrice Komas, and Roger Pelle.

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

[CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

Citation: Koyaweda GW, Macharia R, Ongus JR, MachukaE, Pelle R, Komas NP (2022) In silico Analyses of Hepatitis B Virus Genotype E Strains from Treatment Naive Central African Patients Reveal Important Mutations in the Complete Genome. J Antivir Antiretrovir. 14:232.

Received: 15-Apr-2022, Manuscript No. JAA-22-16862; Editor assigned: 20-Apr-2022, Pre QC No. JAA-22-16862(PQ); Reviewed: 11-May-2022, QC No. JAA-22-16862; Revised: 18-May-2022, Manuscript No. JAA-22-16862(R); Accepted: 27-May-2022 Published: 27-May-2022 , DOI: 10.35248/1948-5964-22.14.235

Copyright: © 2022 Koyaweda GW, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.