Journal of Psychology & Psychotherapy

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0487

ISSN: 2161-0487

Review Article - (2020)

Some positive psychologists claim that quantitative research leads to the most effective interventions for the intentional pursuit of happiness. A similar claim made in psychotherapy research resulted in failure; fifty years of experimental research has not improved psychotherapy outcomes. In this essay it is argued that the explosion in happiness studies of the last twenty years did has not improved effect sizes of happiness interventions. The supposed epistemological superiority of positive psychologists has not produced more effective happiness advice. This should not be taken as an encouragement to throw the baby out with the bathwater. If we follow current reasoning in psychotherapy research, we can conclude that positive psychological research can correct misguided or counterproductive happiness advice, but will not offer definitive answers. The individuals making his their own choices on the basis of a personal life philosophy count. A further conclusion is that happiness interventions should not just be about acquiring skills to correct the affective system in our brains, so that we are able to overcome our negativity bias or hedonic adaptation. Intervention should also be about following our emotional action tendencies; promoting doing to do more of what feels right to us and avoiding what causes pain.

Happiness; Positive psychology; Emotion; Happiness advice; Evidence-based psychotherapy

The world has a habit of recycling its best ideas. One idea is that surfaces again and again is that science and practitioners should not only focus on studying and repairing what goes wrong, but also on observing and strengthening what is good. We find this idea in humanistic psychology with its focus on self-actualization and the importance of ‘being needs’ compared to ‘deficiency needs’ [1]; in psychiatry with a focus on recovery and maintaining people in the community, instead of fending off relapse and deterioration [2]; in health care with the concept of positive health that can be defined as the ‘ability to adapt and self-manage, in light of the physical, emotional and social challenges of life’ so that health care no longer strives for the total absence of physical, emotional and social pathology [3]; in dementia care with a focus of personhood and citizenship and not just on brain damage [4]; in solutionfocused therapy with its focus on strengths and competency and not on assumed deficits and pathology [5], and of course in positive psychology, the ‘science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions promises to improve quality of life and prevent the pathologies that arise when life is barren and meaningless’ [6].

The idea that we should strive for the positive has added to the quality of life of countless individuals and of the professionals that use this idea. It is my personal impression that of all the examples mentioned above, positive psychology has been most widely disseminated to the general audience. This raises question about the ‘marketing strategies’ of positive psychologists. How do they present the main ideas in the public domain?

If you want to gain an impression of the public image positive psychologists strive for, you can start with the self-help book The How of Happiness; A New Approach to Getting the Life You Want, by Sonja Lyubomirsky [7], a leading happiness researcher. The publisher Penguin Books has devoted the first three pages to reviews praising the book. For example, Arianna Huffington is quoted: “Our founding fathers told you it is our right to pursue happiness - but they left it vague about how to attain that holy grail of modern life.’ But now Lyubomirsky shows us the way to a life of purpose, productivity and joy.’

The praise of well-known positive psychology scholars falls into two categories. The first is that happiness is made easy. You should just follow the ideas and suggestions set out in Lyubomirsky’s book. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes that the book ‘provides practical suggestions for improving one’s life that are easy to follow’. Susan Nolen-Hoeksema tells us this is ‘the authoritative guide to what makes us happy and how to achieve happiness’. Barry Schwartz mentions the ‘sound, practical recommendations to make life more satisfying.’ If you know how, you can just do it.

The second theme praises the scientific background of Lyubomirsky. Charles Nichols writes in The Journal of Positive Psychology ‘As I was reading it, I kept wishing I had a stack of copies I could give away to the various people I’ve heard over the years endorse faulty theories of happiness or whom I’ve observed pursuing unprofitable approaches to become happier.’ Barry Schwartz mentions the ‘cutting edge psychological research’, Martin Seligman the ‘science-based advice’, and Susan Nolen- Hoeksema speaks of a ‘world authority on happiness research’.

These eminent psychologists state that Lyubomirsky’s happiness advice is superior, because she knows the science best. Daniel Gilbert drives this message home with Trumpian self-indulgence. ‘Everyone has an opinion about happiness, and unfortunately, many of them write books. Finally we have a self-help book from a reputable scientist whose advice is based on the best experimental data. Charlatans, pundits, and new-age gurus should be worried and the rest of us should be grateful. The How of Happiness is smart, fun, and interesting-and unlike almost every other book on the same shelf, it also happens to be true.’

I always imagined that Lyubomirsky would be a bit embarrassed by this lavish praise, because in the book she tells us that her advice is not that different from the things her grandmother told her when she was young. In a later book, The Myths of Happiness; What should make you happy, but doesn’t, what shouldn’t make you happy but does Lyubomirsky [8] seems less modest. Her readers should not pursue happiness using common sense or the counsel of wise relatives, but let themselves be guided by data taken from happiness researchers. For example, if you a fed up with your partner and ask yourself the classical question ‘Should I stay or should I go?’, Lyubomirsky tells you: ‘The sooner you consider the research, the sooner you will be prepared to make a decision based on reason rather than intuition’. The ‘vague’ founding fathers do not only have a worthwhile positive idea, but also found solid ground in using this guiding principle in daily life.

Happiness is easy

The first theme of the public praise for Lyubomirsky is that everybody just needs to follow her advice to increase their happiness. I do not suggest that this is a main theme in her own thinking and papers, but I will devote a lot of attention to it, because it seems to be a major theme in the way positive psychology is sold to the general public.

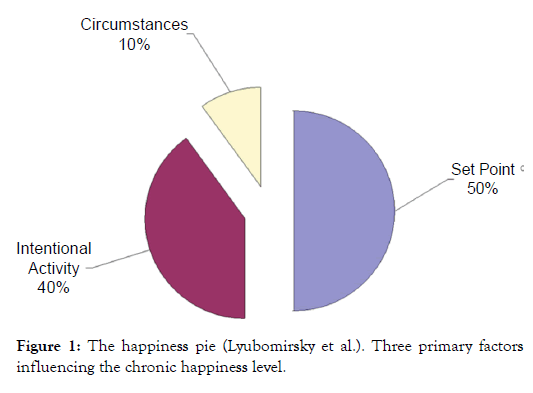

The cover of the how of Happiness features one of the most used models for popularizing positive psychology, the happiness pie. A little less than half of the pie is missing and next to it a text states that ‘This much happiness - up to 40%- is within your power to change.’ The message is existential: ‘life is what you make it’, although Lyubomirsky also mentions that 50% of our happiness is due to genetic factors and 10% to life circumstances. It is worthwhile to note that the percentages are derived from data gathered to explain differences in happiness between respondents, and not the intra-individual factors associated with happiness [9].

Being married or not does not explain a lot of happiness between individuals, but if you are married to an aggressive, unemployed alcoholic, who threatens to harm your children, this circumstance may be a better predictor of your happiness than your intentional capacity to think positively about his or her future character development [10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The happiness pie (Lyubomirsky et al.). Three primary factors influencing the chronic happiness level.

A problem with the happiness pie is that it is theoretically and empirically flawed. Theoretically, because the reasoning is too simple. Lyubomirsky, Sheldon and Schkade [9] ascribe fifty percent of happiness to genetic factors and ten percent to circumstances and infer that the other forty percent must be due to intentional activity. It is quite a leap of faith to explain all the unexplained variance by one single factor. Coincidence and person-environment fit are also plausible candidates to explain part of the variance. The happiness pie is also empirically flawed. Brown and Rohrer [11] have shown that the percentages chosen from the literature are biased. Using the same data and literature and data to recreate the happiness pie, it would be just as reasonable to estimate that five percent of the happiness variance is explained by intentional activity.

Sheldon and Lyubomirsky [12] state that they mostly agree with the analysis of Brown and Rohrer. Pursuing happiness is harder than was estimated in 2005. The ‘pie chart diagram appears to have outlived its usefulness’. Most experts seem to agree, according to a recent Delphi study in which 14 leading scientists (including Sonja Lyubomirsky) rated the effectiveness of the development of skills for greater happiness, using self-help or professional coaching. The effectiveness of the training of skills to change intentional activity was rated 3.1 of a 5-step scale. The experts had more confidence in happiness increasing techniques such as ‘Invest in friends and family’ and ‘Get physical exercise’, which were rated with a (4). Getting children (2,7) or gaining wealth (2.8) was rated lower than skill development with self-help or professional coaches [13].

Marketing positive psychology by stating that happiness is made easy, can also be judged on the basis of the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions (PPI’s). Four major meta-analysis lead to the conclusion that the interventions have positive but modest effects. Sin and Lyubomirsky [14] report a small effect (mean r = +0.29, median r = +0.24) on ‘well-being’. Bolier et al. report a similar effect (d = +0.34) on subjective well-being, that partly waned at follow-up (d = +0.22) and after the removal of outliers (d = +0.17). In a recent re-analysis of the studies included in the first two metaanalyses mentioned above White, Uttl and Holder [15] used an improved correction for small sample sizes and found an smaller effect of d = 0.1 of PPI’s on well-being. Hendriks et al. have shown that multi-component PPI’s have a small to moderate effect on subjective well-being (Hedges’ g = +0.34). The removal of outliers or low-quality studies lowered the effect on well-being (g = + 0.24 without outliers, g = +0.26 for high quality studies). Another recent meta-analysis that analyzed the effects of randomized controlled positive psychological interventions on subjective and psychological well-being, found an overall effect size (Cohen’s d value) of 0.22 for subjective well-being [16]. Taken together these meta-analysis lead to the conclusion that the skills trained are of limited importance for happiness or that the efforts to train them do not increase competence very much. Happiness is not made easy, but training does increase the probability that one can be happy.

A possible caveat against this conclusion is that the concept of well-being is quite fuzzy [17] and the data may reflect the operationalization of well-being instead of happiness. Bergsma, Buijt and Veenhoven (in press) used the World Database of Happiness for a research synthesis focused on interventions designed to increase happiness. In this study the concept of happiness was strictly defined as the degree to which individuals judge the overall quality of their life-as-a-whole favorably [18]. The PPI’s were found, on average, to have had a positive effect on happiness of five percent on the theoretical scale range. This effect is comparable to an increase in household income of about € 1.250 for an average German household. Stated this way the five percent increase is impressive. An alternative way to look at it, is that five percent borders on a just noticeable difference. Again the data reveal a worthwhile, but modest effect. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky [12] acknowledge that happiness advice does not work miracles. They summarize the state of the art with respect to the pursuit of happiness as follows: ‘Happiness can be successfully pursued, but it is not “easy”.’

The conclusion is that positive psychology promises more than it can deliver. If somebody asked me personally how to achieve more happiness, than I would recommend Lyubomirsky’s The How of Happiness as an excellent starting point, although I would suggest to tear the sales pitches out of the book.

Positive psychology has improved happiness training

The second theme running through the praise for Lyubomirsky is that her happiness advice is better than that of others, because it is substantiated by data taken from empirical studies. This is one of the central distinctions between humanistic psychology and positive psychology. Humanistic psychologists tend to prefer qualitative research methods. Positive psychologists argue that they added scientific rigor to the speculation of humanistic psychologists by employing quantitative methodologies requiring rigorous experimental and/or statistical techniques [19].

Sheldon and Lyubomirsky [12] defend the selective use of data in the happiness pie chart, by referring to the differences in epistemology between humanistic and positive psychology. Their conclusion that about the forty percent of happiness could be explained by intentional activity ‘supported the nascent science of positive psychology, helping to justify its search for new ways to help people activate their potentials’. I hope this is a retrospective justification, but if we use Gilbert’s language and if you allow this essay to be cynical, I could say that the happiness pie bended the truth, to be able to find the means to do research to find the truth. Science is a social activity, but I guess it is possible to put too much emphasis on the politics.

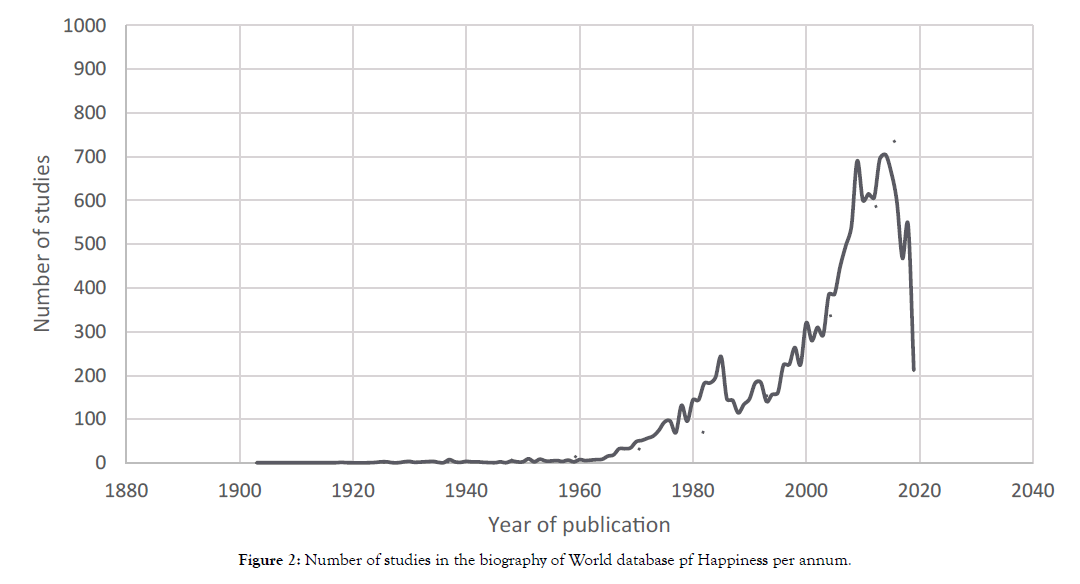

After twenty years of positive psychology, we can try to evaluate if quantitative research has increased the quality of happiness advice and has made happiness easier to achieve. If not, it is not because of a lack of trying. In 2020, we can safely conclude that the nascent science of positive psychology has blossomed and today there is an increasing number of journals devoted to various aspects of the field. See for example: the Journal of Positive Psychology, the Journal of Happiness Studies, the Journal of Well-Being Assessment, the Journal of Wellness, Applied Research in Quality of Life, and the European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology. If we focus of the number of scientific publications on happiness that are entered in the World Database of Happiness, we see a steep rise since the start of this century [20]. Note: the fall in publication numbers in the last two years does not indicate a decline in happiness studies, but is an artefact of delays in entering studies in the database (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of studies in the biography of World database pf Happiness per annum.

Scholars, coaches and trainers that want to increase the quality of happiness advice, have a richer pool of studies to draw from than for example Fordyce [21,22] had at his disposal when he started his pioneering work on happiness training techniques. Fordyce could read 788 studies (year 1976) on happiness. In 2020 the number was increased to 14.491.

If positive psychologists are right about their idea that science will improve interventions aimed at increasing happiness, than it should be visible by now. The history of psychology leaves room for doubt. We can take data about psychotherapy, probably the best researched form of psychological advice, as an example. A recent meta-analysis on psychotherapy for young people, spanning 53 years (1963-2016) and 453 RCTs (31,933 participants) found no trend for increasing effectiveness of psychotherapy, although there is strong empirical support for treatment [23]. All the considerable efforts to improve psychotherapy using quantitative research efforts have not substantiated in improved therapy outcomes. This insight is not new. Luborsky, Singer and Luborsky [24] famously suggested we use the verdict of the Dodo in Alice in Wonderland: ‘Everyone has won and all must have prizes.’ Empirical research has yet to help us come up with a winner. Miller et al. [25] state that we know that psychotherapy works, but we do not know how it works.

It is difficult to think of a reason why the sobering results of psychotherapy research should not apply to the field of happiness advice. One could even argue that translating scientific progress into better happiness advice is even harder for positive psychologists than for psychotherapists. The kind of problems to be solved by the different disciplines may be a challenge for positive psychologists. People with mental health problems experience suffering that can serve as an incentive for them to try to change their lives, whereas this motivation may be less strong for people seeking happiness. Another problem for positive psychologists is that finding a solution to a specific mental health problem may have less alternative approaches than finding happiness. Happiness philosophies offer many different possible ways to pursue happiness [26]. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky [12] add to this argument and write that the pursuit of happiness is difficult ‘to investigate via double-blind experiments, the gold standard of psychological research, because the successful pursuit of happiness typically requires awareness, knowledge, and intentional buy-in by participants.’ Establishing what works for whom in what circumstances will require a huge research effort and the opinion and active role of the recipient of the advice remains crucial [27].

No positive trendline in effect sizes of happiness advice

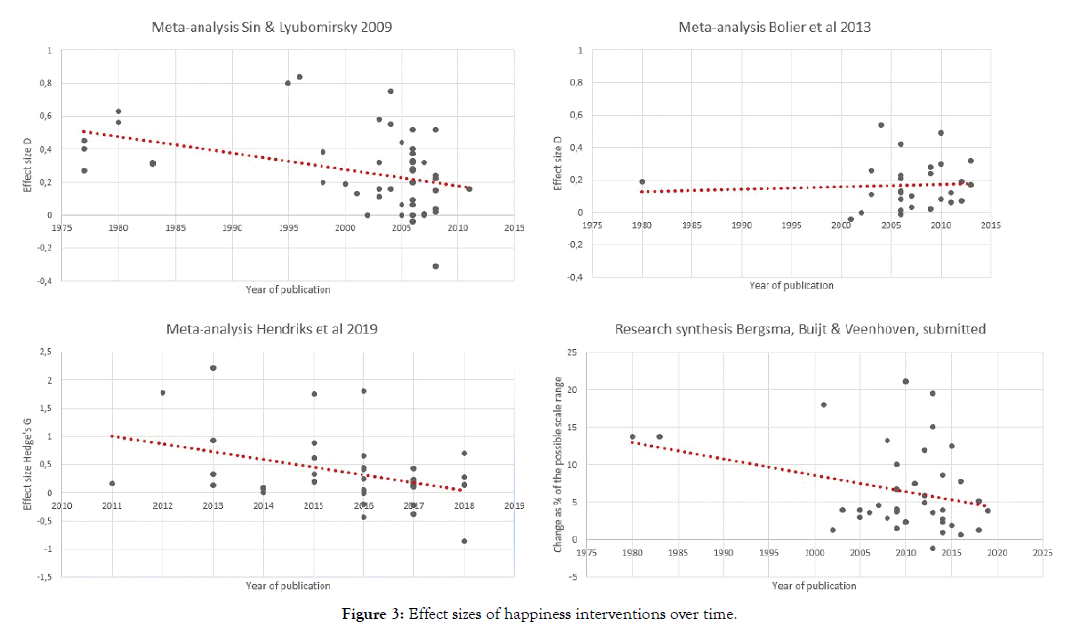

The argument against the basic tenet that experimental studies can significantly improve happiness training techniques has been purely theoretical thus far, but after twenty years of research it is possible to assess empirically if positive psychologists outperform psychotherapy researchers and have increased the effectiveness of its interventions over time. To assess if interventions designed to increase happiness had improved, I entered all the dates and the effect sizes of individual studies incorporated in the existing metaanalysis into an Excel data sheet and used Excel to calculate a trend line. Note: for the studies of Sin & Lyubomirsky [14] and Bolier et al. [28], I used the recalculated effect sizes by White, Uttl & Holder [15], because of some inconsistencies found in the original calculations (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Effect sizes of happiness interventions over time.

Three negative trendlines and one neutral trendline in Figure 3 seem to confirm that additional scientific studies on happiness do not automatically lead to improved outcomes of happiness advice. The meta-analysis of Koydemir, Sökmez & Schütz [16] yielded a slightly positive trendline for all the studies, but this turned negative, when three studies before 1990 were skipped (data not shown). In general, there is no sign of improvement of happiness advice due to increased availability of empirical data from happiness studies and some worries with respect to diminishing effects of happiness training interventions.

It should be noted however that it is unsure whether the negative trendline is a real phenomenon. It also could be an artefact of the lacking quality of the studies [29], the use of insensitive measures or the use of samples or delivery methods that are related to the effect sizes of PP interventions. For example, interventions based on traditional methods were found to be more effective than those that used technology-assisted methods and perhaps the latter are used more often recently [16]. I therefore do not postulate a negative trend, but I do reject that there is an empirical ground to sell positive psychology interventions as superior to other forms of advice thanks to the research efforts in quantitative happiness studies, as is implied by the top experts in praising Lyubomirsky.

An explanation for the lack of a positive trendline may not be the failure of positive psychology, but its success. The ideas of positive psychologists to increase happiness have found their way into the mass media and for example Lyubomirsky and others have reached audiences way far beyond the reach of scientific journals [27]. A related explanation comes from the law of diminishing returns. The clients of positive psychologists, and psychotherapists, change over the course of time, because they incorporate ideas of professionals and become ‘protoprofessionals’ [30]. Professional happiness advice may have improved, but the knowledge of the professionals may have less additional value for the more knowledgeable clients. An possible illustration of this explanation is provided by the study of Lichter, Haye and Kammann [31]. They succeeded in increasing happiness of students with the help of erroneous zones concept described by self-help guru Wayne Dyer [32]. Dyer stimulated readers to increase positive self-beliefs. Discussing these beliefs in a group was useful In New Zealand in the seventies, but the same might not be true in 2020, due to changing circumstances. These days everybody seems to get a fair dose of inspirational quotes from Facebook and almost any young person has practiced the art of positive self-presentation on social media. Dyer’s erroneous zones may have nothing new to offer for new generations. The opinion of Dyer’s work also seems to have changed over the years. Lichter, Haye and Kammann [31] describe the erroneous zones as ‘entirely compatible with the cognitive therapy literature’, but at the end of the nineties the work was no longer recommended by psychologists. An exaggerated belief in your ability to control yourself and the world, as propagated by Dyer, has been replaced by an emphasis on the acceptance of life’s inevitable travails [33].

To summarize, the idea that data taken from positive psychology research improve happiness advice must be classified as an unproven hypothesis. Positive psychologists share the same predicament of psychotherapy researchers; both groups deal with very sensitive issues that are of central importance to people’s lives and both groups can show that their toolkits are useful for average consumers, but neither group can reasonably claim that their own solutions are superior to these of others with a different philosophy. It is easy to say that the new age happiness advisers are charlatans, as Daniel Gilbert has done, but he forgets that some of the ‘charlatans’ may have fruitful ideas [34].

Rethinking happiness advice

We have learned so far that experts praising Lyubomirsky have exaggerated claims about the effectiveness of happiness advice by positive psychologists and that there is no clear indication that empirical, quantitative studies have improved the existing happiness training techniques. The question is: will this conclusion be upheld in the coming decade, or will it turn out to have been a feature of the growing pains of a young science?

The example of psychotherapy research suggests that perhaps positive psychology should abandon the ‘road best travelled’. Miller et al. [25] summarize their overview of the field of psychotherapy as follows: ‘The hope has been that knowing how psychotherapy works would give rise to a universally accepted standard of care which, in turn, would yield more effective and efficient treatment. However, if the outcome of psychotherapy is in the hands of the person who delivers it, then attempts to reach accord regarding the essential nature, qualities, or characteristics of the enterprise are much less important than knowing how the best accomplish what they do.’ Psychotherapy research should no longer seek the ultimate truth about what is the best therapy, but should delve in the pragmatics of the individual providing excellent therapy. The same line of reasoning can be applied to happiness advice, although I would certainly add that Miller neglects the role of the client. There are excellent therapists, but it is the client doing the hardest work when it comes to realizing personal growth.

Miller et al. [25] describe three steps necessary to create the best outcome in psychotherapy: ‘(1) determining a baseline level of effectiveness; (2) obtaining systematic, ongoing, formal feedback; and (3) engaging in deliberate practice.’ I will follow these steps and apply them to happiness advice. The first of these step covers common ground, while the last two steps are more explorative.

Baseline effectiveness

The first step described by Miller et al. [25] is business as usual for positive psychology. Scientific work to find the best possible solutions to pursue happiness should continue, although it would not hurt if researchers were a little less sectarian and included the wisdom of humanistic and existential psychologists, philosophers and religious and spiritual leaders. The motto for the first step could be that while it may be impossible to outperform serious alternative approaches to increase happiness, it is possible to make serious mistakes: the truth may not exist, but this does not mean it is impossible to lie. We should resist the conclusion that anything goes and that qualitative and quantitative evidence does not matter.

A convincing example of the argument against ‘anything goes’ would be the work of the great pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer [35]. His intellect and his place in philosophies hall of fame might reassure readers that his self-help book on the art of achieving happiness can be trusted, but his advice is clearly counterproductive at times. The data of happiness studies for example indicate that happiness is linked to having satisfying social relationships, but Schopenhauer teaches his readers to distrust others [36]. He writes things such as:

• Pare essentially only interested in themselves. Therefore they are both easily offended and flattered. People’s opinions and judgments’ are usually corrupt and easily bought.

• Being friendly and kind to other people will make them arrogant and intolerable. Never let yourself become dependent on someone. Always behave with a little disregard.

• Friendship is usually concealed self-interest.

• Exhibiting intelligence and discernment makes you very unpopular because it confronts other people with their intellectual inferiority.

Schopenhauer’s view on social relationships runs counter to what we know about the importance of satisfying the need for relatedness for happiness, so taken his self-help advice seriously would probably harm the happiness of readers [37]. The How of Happiness [7] might not be more effective in increasing happiness than the work of some new age gurus [36], classical philosophers such as Epicure [38] and Confucius [39] or the counsel of a wise grandmother, but Lyubomirsky did what was possible to prevent mistakes and therefore her book almost certainly beats that of Schopenhauer. Scientific knowledge is important and allows us to bring some basic hygiene into the field.

Ignoring the evidence base may also tell us something about the qualities of the person that offers his or her counsel. It is difficult to imagine that some guru can give optimal happiness advice, if he or she does not have the curiosity and tenacity to devote sufficient attention to finding out what is right or wrong. An interesting observation in psychotherapy research related to this line of thinking is that the most effective psychotherapists more often notice that they make mistakes than average psychotherapists. The keen awareness of what might go wrong is an essential ingredient of psychotherapeutic excellence [40]. The same may be true for happiness counsellors.

Lyubomirsky’s use of the evidence base is a strong feature in The How of Happiness and a valid reason for praise. Take for example Schopenhauer’s [35] remark that a person can be considered happy if he or she is unhappy, about small things. Schopenhauer has found a comic way to confront the reader with the idea that the pursuit of happiness may disappoint. Lyubomirsky also highlights that improving one’s life does not always lead to sustainable increases in happiness. Schopenhauer may be funnier, but Lyubomirsky clearly wins the contest, because she can explain the process of hedonic adaptation and the steps one can take to beat this process, for example investing in experience instead of material goods.

Knowledge about the baseline effectiveness of interventions does matter. Sheldon and Lyubomirsky [12] offer a summary of important insights from the evidence base present in happiness studies, that stimulates the basic hygiene in the field: ‘The pursuit of happiness requires selecting self-appropriate and eudaimonictype activities (rather than chasing after positive emotions directly); investing sustained (rather than desultory) effort in those activities; and also, practicing these in a varied and changing manner (rather than doing them the same way each time). By such means, people can create for themselves a steady inflow of engaging, satisfying, connecting, and uplifting positive experiences, thereby increasing the likelihood that they remain in the upper range of their happiness potentials.’

Systematic, ongoing feedback

The second step in improving psychotherapy is that psychotherapists should register the effects of their own behavior. It is not superior knowledge of what to do that make therapists excellent, but the effort they put in gaining feedback form a client and to monitor the therapeutic process, so that they can fine-tune their interventions for specific clients [25].

At first it sounds silly, to apply the idea that we need systematic, ongoing feedback to an individual seeking happiness. Even for psychotherapists this is a chore. The authors who recommend using the continuous corrective feedback warn therapists that this ‘feels challenging and hard; not inherently enjoyable or immediately rewarding’ [40]. Pursuing happiness seems to lose its point if you have to optimize the positive affect by putting all your data in a spreadsheet. Pursuing happiness may be hard work, but it should not be a tedious chore. This objection may lose much of its appeal when we realize that our brains have evolved to register systematically how we are doing. The brain has a hedonic system built in that constantly registers, whether we like things or not, although we are not always conscious of our judgement at the moment [41].

Positive and negative affect is an elementary aspect of the way mammals regulate their interactions with the world. Emotions help us to prioritize what to avoid and to seek stimuli that are relevant for our needs, such as food, sex, infants, social relatedness and meaning. Pain gives the incentive to avoid a current situation, while pleasure motivates mammals to approach or to stay in the situation as it is [42-44].

The innate, automatic tendency to feel good or bad about our interactions with the world is described by Kahneman [45] as a part of thinking fast, who contrasts it with the deliberate effort that is needed to think slowly. Thinking fast or slow has important implications for the happiness pie and the way we think about the pursuit of happiness. As discussed, Lyubomisky, Sheldon & Schkade [9] explain all the unexplained variance in happiness as intentional activity. They do not offer an explicit definition of intentional activity, but the phrase certainly suggests that it is falls under Kahnemann’s slow thinking. And indeed, the happiness interventions offered by positive psychologists, are often aimed at correcting automatic tendencies of the brain, such as hedonic adaptation and the negativity bias [46]. According to positive psychologists our brains get used to the good things in life too fast and have an innate tendency to focus more on the negative side of our lives. A deliberate focus on gratitude and gratefulness is a strategy commonly recommended to overcome such hedonic adaptation [47] and increasing our mindfulness may help us to deal with our negativity bias [48].

Using the phrase ‘intentional activity’ frames the pursuit of happiness as a fight to overcome the ‘construction failures’ of our brains. This may explain why Lyubomirsky [8] tells readers not to trust their feelings, but to be rational in making life choices, and follow the trend in the data positive psychologists have accumulated. This attitude also shows in the papers she writes. For example: ‘Making it last: Combating hedonic adaptation in romantic relationships’ [49].

If we construe the pursuit of happiness as a battle with thinking fast or human nature, then it is of small wonder to think of it as hard, although not impossible. A more constructive view might be that we frame the pursuit of happiness not just as forcing the mind to experience the world in a positive way, but also as following our emotional instincts and just do what feels good. Happiness is easy as is shown by populations around the world that are fortunate enough to live in wealthy, democratic countries with low levels of corruption, violence and restrictions of freedom. When human needs are met, the overwhelming majority of people are happy [50]. The basic, instinctive parts of our brains appreciate the enormous progress that has been in societies since the Enlightenment [51].

Pursuing happiness is within reach of average brains in favourable living conditions. Perhaps the pursuit of happiness should be just as much about listening to the messages of our emotions and moods and choosing our behaviour accordingly, as it is about creating more pleasant feelings [52,53]. To put it in a slogan: think fast when appropriate and think slow when necessary. After all, our emotional brain is not without its flaws. We are for example not very good at affective forecasting, in predicting the affective consequences of the choices we make. Doing some hard thinking about setting priorities and about finding new solutions to life’s problems is therefore necessary every now and then.

The suggestion that positive psychologists should devote less effort in correcting human nature and allow people to follow it, is of course not without predecessors in psychotherapy. Carl Rogers [54] already stated the supposed superiority of the knowledge of therapists was an illusion. ‘Non-directive counselling is based upon the assumption that the client has the right to select his own life goals, even though they may be at variance with the goals that the counsellor might choose for him. There is also the belief that if the individual has a modicum of insight into himself and his problems, he will be likely to make this choice wisely.’ Rogers idea has survived for example in solution-focused therapy [55], motivational interviewing [56] and coaching [57].

The excellent therapists need systematic ongoing feedback from their clients, because they cannot simply explain how to solve life’s difficulties on the basis of their expert knowledge. Part of the success of psychotherapy can be attributed to the fact that the therapists helps clients to have a clearer insights into their own patterns of thinking, behaviour and feeling. A similar process may be established in seekers of happiness, by making them more conscious of the automatic affective experiences. This can be done by keeping an (electronic) diary or using mood tracking. The idea behind these approaches is that mood awareness will help the individual to find a way of life that fits him or her [58,59]. A recent research synthesis has shown that increasing mood awareness may be the most effective single-method intervention one can use to raise happiness, and it had on average higher results than training skills such as mindfulness, gratitude, kindness and savouring.

The use of systematic feedback to increase mood awareness is not without limitations, and we should realize that (a) it is still a step to translate mood awareness into a life-change for the better, (b) greater awareness can backfire when you realize you are unhappy and you are unable to do anything about it, and (c) these mood awareness interventions that have been empirically tested require effort and high levels of attrition are reported [58].

The empirical base of the importance of mood awareness is still very modest, but the point is that the knowledge about baseline effectiveness and personal mood awareness cover two different sources of information. The positive psychologist that knows the data on general effectiveness and on what works for whom, does not know what the application of a specific skill feels like for the individual. The client has important knowledge about his or her affective experiences that should be used to choose a course of action. Suggesting that positive psychology offers the truth encourages readers to just follow the advice and ignore the messages of the effective messages in their own brain. This may even have some iatrogenic effects and may cause learned helplessness in people that do not improve after following the advice. It is not without reason that recovery oriented mental health practitioners are advised to show modesty and tentativeness about the limits of professional knowledge [60]. People seeking happiness advice should not only inform themselves about the how of happiness, but also register the ‘systematic, ongoing feedback’ of the emotional parts of their own brains.

Deliberate practice

The third way to improve therapy outcomes is to become a reflective or deliberate practitioner. Miller et al. [25] describe this as follows: ‘Deliberate practice means setting aside time for reflecting on feedback received, identifying where one’s performance falls short, seeking guidance from recognized experts, and then developing, rehearsing, executing, and evaluating a plan for improvement.’

If we incorporate this idea into the individual pursuit of happiness, I would suggest making the deliberate practice less instrumental. The question should no longer be how to optimize happiness, but much more about understanding the advantages and the disadvantages of the choices we make. An individual that deliberately seeks happiness, may decide that it is important for him or her not just to increase happiness, but also to experience life to the fullest.

Deliberately seeking happiness is about finding a philosophy in life, and one may for example decide that being right is more important than being happy, or that negative emotions are not always bad [61,62]. A popular example of this line of reasoning comes from the Dutch (Flemish) book, with the title that translates to The art of being unhappy, by psychiatrist Dirk de Wachter [63]. Not a single contribution from positive psychologist has made its way to the references, but his book was sold very well and De Wachter has been prominent in the media since publication. According to Gilbert’s praise of Lyubomirsky, it is unfortunate that De Wachter felt the urge to write a book on happiness without knowing the science inside out. I however, do think De Wachter makes interesting points, for example that suffering should not be regarded as a failure, but as an invitation to share existential burdens and to connect with others. Just to mention a small example: some positive psychologists in The Netherlands advice you to not follow the news, because it makes you feel bad. According to De Wachter it is more important that you know what is going on than how you feel about it. Following the news can be part of a legitimate, deliberate life philosophy.

It is impossible to present an overview of all the different sources for the deliberate pursuit of happiness. I will just mention some well-known examples that have been a personal inspiration for me. The Raids on the Inspeakable by the monk and poet Thomas Merton [64], the search for meaning in the concentration camps by the inventor of logotherapy Viktor Frankl [65], the description of what it means to be an individual in the light of the quest of Don Quixote [66], the work on wisdom as the hard work that needs to be done to find the truth in clichés, whether it is done by a scholar [67] or a novelist [68], the psychoanalyst Jung [69] who tried to get to know himself all his life, and confesses in the last page of his autobiography that he experiences himself as a stranger at old age, Frijda’s [70] reflections on the laws of emotion, Paulo Coelho’s [71] work The fifth mountain that shows compassion for people that rage against faith and Albert Camus’ [72] ideas about the happiness of Sisyphus and the absurdity of life. I was moved to tears by the wordless animated film The Red Turtle by director Michael Dudok de Wit, in which the ship-wrecked human being is just another organism of the deserted island [73], and I felt I was changed somehow by watching the film, although I cannot put words to what the experience has done for me. A special mention deserves Sara Ahmeds [74] reflections on the promise happiness as a way to control people. Feminists were put into place with the idea of the ‘happy housewives, black critiques had to battle the ‘happy slaves’ and queer critiques had to conquer the idea of heterosexual ‘domestic bliss’.

My last example comes from the Dutch psychologist Aukje Nauta [75] who told her audience in her inaugural lecture about organization psychology at Leiden University in the Netherlands that we need more love at work. If you boil all psychological theories down to their essence, it can be said that we need love for good cooperation. Nauta knows all the complexities of psychological theories and still describes her central message in the form of plain common sense, without discrediting the research of her field in any way.

Two claims have been central in the marketing of positive psychology interventions and their role in the pursuit of happiness. The first selling point that the intentional pursuit of happiness is made easy thanks to scientific studies is overdone, which is recognized by experts such as Lyubomirksy. The second marketing idea is that positive psychology offers a vast improvement in happiness advice, thanks to the scientific rigor and quantitative research designs. This claim has not received empirical support, and there even is an indication of a decline in the effectiveness of following happiness training over time. This negative trend can probably not be explained by deteriorating quality of the intervention used in the pursuit of happiness. The happiness interventions used for scientific evaluations have not changed much. In the multiple positive psychology techniques studied by Hendriks et al. or the studies included in several meta-analysis [14,16,28], I can find no example of ‘faulty theories of happiness’ or ‘unprofitable approaches to become happier’.

This possible trend of declining effectiveness of happiness training interventions is difficult to reconcile with the promise that more happiness studies will improve the quality and effectiveness of happiness advice. Knowledge about positive psychology interventions is important for basic hygiene of the field, and its baseline effectiveness, but it is a unethical to sell the opinions of even the best experts as the ultimate answer to the questions life poses us [76]. Or to borrow the words of Alexandrova [77] for a different context: The lavish praise of positive psychologists for themselves violates ‘the main assumption of the subjective approach - that when judging happiness, the authority of how to weigh different aspects of our lives and experiences belongs to the subject’. Perhaps it is too early to tell, but it seems that positive psychology has stumbled upon the dodo verdict. Pursuing happiness is not a tame problem, for which a definitive answer about the best way to pursue happiness can be found, but a wicked problem, without definitive answers [78].

Miller et al. [25] suggest a way to proceed: we should focus less on what works, and more on how the pursuit of happiness works for whom. This implies that positive psychologists should keep Rogers’ non-directive imperative in mind. Positive psychologists can teach people to acquire new skills to combat the hedonic adaptation and negativity biases, but the experts should also give people room to connect with the things they already experience and know, so they can use the wisdom that is already built into the basic structure of their brains. The pursuit of happiness should be just as much about following the directive of the basic structures of our brains - doing more of what feels good and avoiding pain - as about correcting the way we perceive ourselves and the world. The expert should encourage clients to develop a personal philosophy of life.

The founding fathers of America came up with the following sentence in their declaration of independence: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ They were probably not vague, but left it deliberately open to each individual to pursue happiness in a way that suited them best. History has proved them right. Freedom turns out to be an important predictor of the happiness of citizens, and there are as yet no indications that freedom has passed its maximum in the freest countries [79].

Citizens may choose to be inspired by the new science of positive psychology, just as I am personally and professionally indebted to the excellent work of Lyubomirsky, but it goes against the spirit of the founding fathers to suggest that somebody is unwise if he or she makes important life decisions without consulting the evidence base of positive psychology. Claims about having found the truth on happiness advice is overdone considering the existing data.

I would like to thank Ivonne Buijt and Ruut Veenhoven for gathering the data used in Figures 2 and part of Figure 3 and for their suggestions for improving this paper. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewer.

No funding

No conflict of interests

All new data freely available at the World Database of Happiness, section correlational Findings, H16 Health, psychological treatment.

Citation: Bergsm A (2020) Diminishing Effectiveness of Happiness Interventions: Positive Psychology Stumbles on the Dodo Verdict. J Psychol Psychother. 10:385. doi: 10.35248/2161-0487.20.10.385.

Received: 06-Sep-2020 Accepted: 08-Oct-2020 Published: 15-Oct-2020

Copyright: © 2020 Bergsm A. This is an open access article distributed under the term of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : None