Orthopedic & Muscular System: Current Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2161-0533

ISSN: 2161-0533

Case Report - (2021)Volume 10, Issue 9

Compression fractures are the most common vertebral fractures. They involve the anterior column of the spine, and are considered stable fractures due to the presence of intact posterior ligaments that resist further collapse and deformity of the spine. Hence, they are often managed conservatively.

We describe a case that was initially diagnosed as compression fractures and managed conservatively. With the abundance of compression fractures and increase in preference for conservative management of compression fractures, it is of utmost importance to recognize the possibility of other spinal co-pathology, especially that of hyperostosis of the spine, both by clinical judgment as well as radiological analysis before embarking on conservative management, should there be under-treatment and development of complications that could have otherwise been avoided, as in the case presented in this report.

Compression fractures; Spinal; Ankylosing spondylitis

Compression fractures are the most common vertebral fractures. They involve the anterior column of the spine, and are considered stable fractures due to the presence of intact posterior ligaments that aid in resisting further collapse and deformity.

They are thus often managed conservatively [1]. Indeed, recent studies have shown that compression fractures can be effectively managed conservatively, with vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty offering no additional benefits to these patients.

These results, however, led to the under-treatment and overdiagnosis of many compression fractures. We present a case of chance fractures which was misdiagnosed as compression fracture.

We hope to emphasize the importance of excluding co-existing pathologies of the spine before labeling the fracture as a compression fracture and undertaking conservative management of these spinal trauma and injuries.

An 85 year old male, who was premorbid ADL-independent with a background of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), presented to the Emergency Department on June 2020 following a low energy fall on the same day at home.

There was no radiation of pain to the lower limbs, no tingling or numbness and no neurological signs or symptoms.

The pain was not aggravated or relieved by postural changes or increase in abdominal pressure.

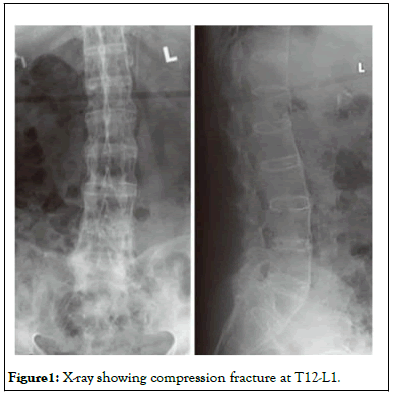

The initial x-ray demonstrated a compression fracture at T12- L1 as shown in Figure 1, and the patient was managed conservatively with brace, bed rest and analgesia.

Figure 1: X-ray showing compression fracture at T12-L1.

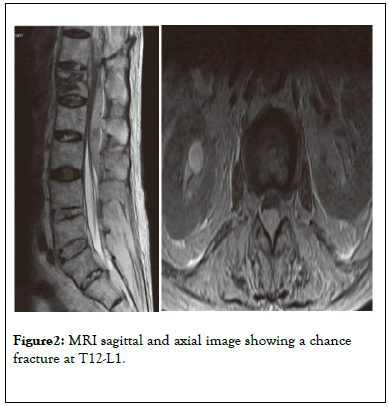

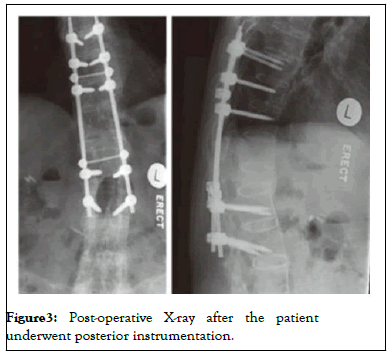

However, due to the persistence of severe back pain, the patient underwent MRI, revealing a chance fracture at T12-L1 as in Figure 2, with the patient undergoing posterior instrumentation and fusion 10 days after the initial presentation. The patient was then discharged 60 days after the initial presentation to the Emergency Department, with the patient able to ambulate independently at the time of discharge with a brace (Figure 3).

Figure 2:MRI sagittal and axial image showing a chance fracture at T12-L1.

Figure 3:Post-operative X-ray after the patient underwent posterior instrumentation.

Throughout history, several classifications of systems have been proposed for spinal injuries, including the frequently used Denis classification based on the three-column concept [2] as well as classifications according to the mechanism of injuries [3]. In the 1990s, the AO Committee for Spinal Classification reviewed these classifications and subsequently developed a more comprehensive system based on the three basic functions of a stable spine described by Whitesides [4], which reflect the ability of a stable spine to resist axial compression forces, axial distraction forces and torsional forces, as well as rotational forces around the longitudinal axis.

By virtue of both compression fractures and chance fractures being thoracolumbar spinal fractures, patients in both clinical scenarios present with lower back pain as the main symptom, with rare neurological deficits since such fractures do not usually involve retropulsion of bone fragments into the vertebral canal [5,6]. However, while compression fractures occur in patients with severe osteoporosis during trivial events, in patients with moderate osteoporosis following minor injuries to the spine and in patients without osteoporosis in severe trauma, chance fractures are typically associated with motor vehicle accidents typically termed as 'seatbelt fractures,' as well as with other mechanisms including falls, sporting events and assaults [7,8]. This overlapping clinical picture, coupled with the subtle radiographical features in chance fractures, could then possibly lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of chance fractures, as in the three cases we have presented.

Radiographic evaluation of compression fractures may demonstrate the classical 'wedge' pattern of fracture. Smith and Kaufer [9] described the differentiation of chance fractures from other fractures by their disruption of the posterior elements of the spine, longitudinal separation of the disrupted posterior elements, minimal or no decrease in the anterior vertical height of the involved vertebral body, minimal or no forward displacement of the superior vertebral fragment and minimal or no lateral displacement of the fractured or superior vertebrae [10]. However, it is paramount to realize that the clinical spectrum of vertebral compression fractures and chance fractures are wide. Mild compression fractures may also have minimal wedging and decrease in anterior vertebral height while severe compression fractures with greater than 40% loss of anterior vertebral height could similarly have their posterior ligaments damaged by distraction, leading to further collapse and deformity. Indeed, numerous studies have reported delayed diagnosis of chance fractures by 24 hours or more to be more than 50% of cases. Evaluation of the spine using computed tomography (CT) or MRI have thus been advocated, with recent literature recognizing CT's increased accuracy and speed in diagnosing thoracolumbar spine fractures compared to conventional radiographs, and the superiority of MRI in excluding occult injuries and spinal cord lesions before labeling the fracture as a compression fracture [11,12].

The importance of obtaining accurate diagnosis of vertebral spine fractures cannot be over-emphasized, since this diagnosis would dictate the management of choice and possibly the complications and prognosis of the fractures. Compression fractures, being stable flexion-compression injuries, are often managed conservatively, with patients with minimal wedging treated with bed rest and analgesia, those with moderate wedging with loss of 20% to 40% of anterior vertebral height placed in a thoracolumbar brace and those with severe wedging with loss of greater than 40% of anterior vertebral height warranting possible surgical management, though controversies exist with regards to their efficacy as compared to placebo surgery. In contrast, however, chance fractures are unstable fractures produced by hyperflexion and distraction mechanisms, and would definitely require either a thoracolumbar brace to ensure no unstable deformity or posterior spinal fusion in the event of instability or neurological deficits. This is especially so in the setting of a Ankylosing Spondylitis background, with multiple papers concluding that the unstable nature of even harmless appearing injuries dictates that most fractures that occur in the background of AS be managed with fixation, as the use of orthosis is ineffective [13].

The significance of these appropriate management methods are due to the complications associated with unstable fractures, as a review by Ritchie et al. demonstrated that a delay in diagnosis and under-treatment of thoracolumbar spinal fractures contributes to neurological deficits in 10.5% of spinal fractures as compared with 1.4% when diagnosed at initial screening[14,15].Indeed, fractures occurring in the setting of AS are associated with increased instability, higher risks of complications and poorer prognosis as compared to compression fractures, thus while their clinical presentations and radiological features are similar, it is paramount to exclude other unstable fractures and co-pathologies of the spine before labeling a fracture as a compression fracture simply due to its commonality and similarity with other clinical scenarios. With the increase in preference for conservative management of compression fractures, it is of utmost importance to recognize the possibility of other spinal co-pathologies, both by clinical judgment as well as radiological analysis before embarking on conservative management, should there be undertreatment and development of complications that could have otherwise been avoided, as in the case presented.

Citation: ANTAO N, DESOUZA C (2021) Compression Fracture in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Case Report. Orthop Muscular Syst. 10:034.

Received: 02-Dec-2021 Accepted: 10-Dec-2021 Published: 22-Dec-2021

Copyright: © 2021 ANT A O N , e t al. This is an open-access ar ticle dis tribut ed under the t erms of the Cr eativ e Commons A ttribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.