Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence

Open Access

ISSN: 2329-6488

ISSN: 2329-6488

Research Article - (2021)Volume 9, Issue 4

Background: Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a series of statistical methods that allow complex relationships between one or more independent variables and one or more dependent variables.

Objective: The study aimed at determining the practice of physical activity using structural equation modeling as statistical approach.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted from August to November 2018 amongst recuperating alcoholics receiving rehabilitation in Asumbi treatment center of Homabay County, Kenya. Structural equation modeling determined the evidence of physical activity amongst recuperating alcoholics.

Results: Structural model parameter estimation indicated that attitude was a better predictor (β=0.62, p<0.001, n=207), followed by subjective norm (β=0.60, p<0.001, n=207) then perceived behavioral control (β=0.55, p<0.001, n=207) was indirectly and directly predicted.

Conclusion: Structural Equation Modeling is a powerful tool for causal inference among the observed and latent variables.

Alcoholism and practice of physical activity uses a variety of well-reasoned conceptual models to explain a number of phenomena [1,2]. Although conceptual models help to propel research, it is often difficult to test such models with conventional statistical approaches such as t-tests, analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple regressions, and chi-squared. One statistical approach that clearly stands out as an obvious choice for testing conceptual models is structural equation modeling (SEM). Structural equation modeling is a widely recognized statistical technique in validating a hypothetical model about relationships among variables. It also provides a structure to analyze relationships between observed and latent variables, and allows causal inference. Its popularity has recently increased in many applications, including medical, health, biological and social sciences [3,4]. One of the main reasons of increasing popularity of SEM is that it provides concise assessment of complex model involving many linear equations. In general, SEM is a technique for multivariate data analysis, and involves a combination of two commonly used statistical techniques [5]: factor analysis and regression analysis. Currently, many journals publish multivariate analysis of data using SEM. In most cases, the model needs to be re-specified based on the values of the goodnessof- fit criteria of the initially formulated model [6]. SEM can be an effective tool to depict relationships between practice of physical activity and alcoholism, and the associated factors. There are many factors associated with practice of physical activity of recuperating alcoholics, including physical activity knowledge, economic status, gender and culture [7,8]. Although information on these variables is readily available in many studies, the response variables are often not directly measurable but are latent, with the observed variables being their manifestations [9,10]. In this study, we investigate the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control variables on practice of physical activity of recuperating alcoholics. We consider the structural equation modeling for this purpose, which is a powerful statistical tool for causal inference among the observed and latent variables.

Study Area and Design

Asumbi-Homabay located in Homabay County, Nyanza region of Kenya formed the study area mainly because of the existence of Asumbi rehabilitation center. This center was purposively sampled with the target that it receives numerous alcoholic patients both males and females from different parts of the country, offers standardized rehabilitation services to alcoholic rehabilitees and it’s accredited by NACADA. This cross-sectional study was conducted from August to November 2018 amongst recuperating alcoholics receiving rehabilitation in Asumbi treatment center of Homabay County, Kenya. Permission was obtained from the School of Graduate Studies. Ethical approval was given by National Council for Science and Technology. We sought informed consent from the respondents who were informed on the research procedures, details, and assured of confidentiality.

Sampling Techniques and Criteria

Purposive sampling technique was used to select Asumbi rehabilitation center as the study site because it’s the only rehabilitation center that admits and rehabilitates exclusively alcoholics. Stratified sampling was used to select 207 respondents from each stratum (males and females). A sample of 129 respondents from the male stratum and 78 respondents from the female stratum was developed.

Inclusion criteria included:

1. Female and male alcoholics aged 15-65 years who were admitted not more than a week prior to start of the study and those who voluntarily consented to participate in the study.

2. Alcoholics exclusively suffering from alcoholism and not other addictive substances

Exclusion criteria included:

1. Alcoholics with active psychotic symptoms were excluded.

2. Alcoholics not intending to complete the three months of rehabilitation in Asumbi center were not inclusive.

Data Collection Instrument and Procedure

A questionnaire with a seven point Likert scale was constructed along a continuum range from totally disagree/not all/extremely unlikely=1 to totally agree/ very much /extremely likely=7 was used to measure all the variables. Higher scores indicated more positive attitude towards practice of physical activity in alcohol rehabilitation. A 7-point scale, with end points of(7) and (1) was used to elicit the alcoholic’s beliefs about significant referents’ expectations on practice of physical activity during alcohol rehabilitation. Another set of 7-point scales evaluated alcoholic’s motivation to comply with significant others’ expectations and was contained in end points (1) not at all and (7) very much. Three items with 7-point response scales elicited the alcoholics’ perceptions on physical activity in alcohol rehabilitation. The anchors were extremely likely (7) to extremely unlikely (1). One additional item measured perceptions of confidence in ability on a 7-point scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) strongly agree(7). Scores were summed and divided by the number of items for a possible mean score of 1 to 6.5; higher scores reflected greater perceived control. Physical activity intention was measured with one 7-point scale, containing end points of strongly disagree(1) and strongly agree (7). The midpoint of the scale represented unsure practice of physical activity during alcohol rehabilitation. To establish validity, the questionnaire was given to two experts to evaluate the relevance of each item in the instrument to the objectives (content validity). The experts appraised what appeared to be valid for the content, the test attempted to measure (face validity). The degree to which a test measured a sufficient sample of total content that was purported to measure was considered (sampling validity). The questionnaire was administered on respondents and the interview responses filled in by the researcher to gather information on the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral on practice of physical activity during alcohol rehabilitation. The respondents were then interviewed through previous booked appointments and each interview lasted for a maximum of 1 hour.

Data Analysis

Data was entered into SPSS version 15 to calculate reliability tests where Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the consistency of the questions. Structural Equation Modelling using AMOS version 7 was used to determine the influence of attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control on practice of physical activity during the rehabilitation of alcoholics. The overall model fit was evaluated using chi-square (CMIN) and relative chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/df), comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), Hoelter’s critical N, and Bollestine bootstrap. Comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI), values greater than 0.90 were considered satisfactory [11]. RMSEA less than 0.08 was also considered satisfactory [12]. CMIN/df was considered fit when it ranged between 3:1 and was considered more better when closer but not less than 1 [13]. Hoelter’s critical N for significance level of .05 and .01 was used where bootstrap samples was set at 200 [14].

Structural Equation Modeling applied to Physical Activity Practice

Structural equation modeling was used to establish whether a model nested based on Theory of Planned Behavior variables applied on physical activity fits the data acceptably well. The default model’s chi-square value was not significant at 0.05 significance level (χ2=200, df=90, p=0.12, χ2/df=2.22) and all other indices indicated the model was acceptable at (RMSEA=.087, CFI=0.91, CMIN/ DF=2.22, TLI=0.89) and Hoelter’s critical N=200 summarized in (Table 1).

| Fit Indices | Recommended fit Measures | Default Measures |

|---|---|---|

| RMSEA | 0.09 or less is better | 0.087 |

| CFI | above 0.9 is good fit | 0.91 |

| CMIN/DF | between 2-3 | 2.44 |

| TLI | >0.8 is good fit | 0.89 |

| Hoelter’s Critical N | >200 adequate | 207 |

| p | > 0.10 good fit | 0.12 |

Table 1: Fit Indices of Default Model.

Key: RMSEA=Root mean square residual; CFI=Comparative fit index; CMIN/DF=Chi-square/degree of freedom; TLI= Tucker-Lewis Index;χ²= Chi-square.

Structural Equation Model

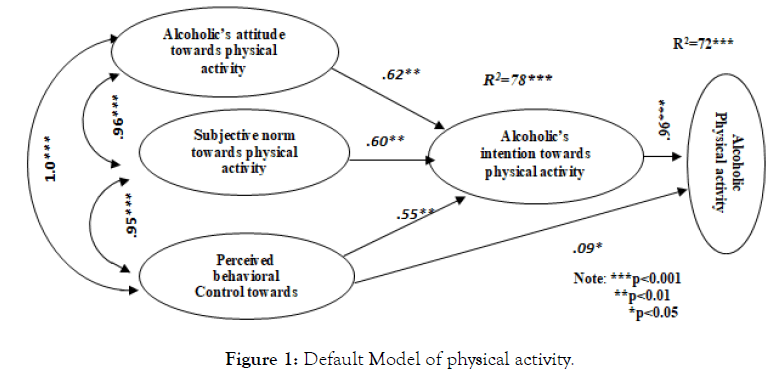

The default model (Figure 1) is the researcher's structural model, always more parsimonious than the saturated model and almost always fitting better than the independence model with which it is compared using goodness of fit measures. That is, the default model (Figure 1) will have a goodness of fit between the perfect explanation of the trivial saturated model and terrible explanatory power of the independence model, which assumes no relationships.

Figure 1: Default Model of physical activity.

Standardized regression weights in (Figure 1), indicated that attitude was a better predictor of intention (β=0.62, p<0.001, n=207), followed by subjective norm (β=0.60, p<0.001, n=207) then perceived behavioral control (β=0.55, p<0.001, n=207) was indirectly and directly predicted. The indirect measure of perceived behavioral control was significant (β=0.55, p<0.001, n=207) while direct perceived behavioral control was insignificant (β=0.09, p>0.05, n=207). Intention in turn strongly predicted physical activity (β=0.96 p<0.001, n=207). The correlation between attitude and perceived behavioral control was statistically significant (β=1.00 p<0.001, n=207). This was followed by the correlation between subjective norm and perceived behavioral control (β=.95 p<0.001, n=207) which was statistically significant. The correlation between attitude and subjective norm was also statistically significant (β=.96 p<0.001, n=207). Intention predictors (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control) put together accounted for 78% of the variance on physical activity intention. Physical activity intention and direct perceived behavioral control put together accounted for 72% of variance on physical activity. The default model was estimated with five latent variables and paths.

This study provides an empirical example of how SEM can be used to explore complex relations between practice of physical activity and associated factors amongst recuperating alcoholics. In this current study, intention in turn strongly predicted physical activity. The correlation between attitude and perceived behavioral control was statistically significant. This was followed by the correlation between subjective norm and perceived behavioral control which was statistically significant. The correlation between attitude and subjective norm was also statistically significant. Intention predictors (attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control) put together accounted for the variance on physical activity intention. Physical activity intention and direct perceived behavioral control put together accounted for the variance on physical activity. This implied that all the TPB constructs were essential predictors of physical activity intention thus the practice of actual behaviour.

Topa G, et al. [15] reported that subjective norm (standardized coefficients =0.82); perceived behavioral control (standardized coefficients =0.34); and attitude (standardized coefficients =0.24) predicted women’s intention to physical activity, with an explained variance of 48 percent to the actual practice. Todd J, et al. [16] reported that all three TPB components had significant correlation on the intention to exercise.These findings were similar to the current study with respect to the improving alcohol rehabilitation, of which attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control all contributed to the intention to practice physical activity.

Previously, Sutton (2016) in a meta-analysis of 72 studies examined physical activity and constructs of TPB and their ability to predict intentions; Attitudes (β =.40) and PBC (β =.33) were the most significant predictors of intentions, while subjective norms (β = .05) were also significant predictors of intentions. Intentions (β =.51) and PBC (β =.51) were noted to have significant impact on practice of physical activity. Similarly, Todd &Mullan [16] showed attitudes and perceived behavioral control were significant predictors of physical activity intentions, with subjective norms being a weaker predictor. It was further argued that attitude and perceived behavioral control accounted for 36 percent of the variance in intention to practice physical activity, but subjective norm was not significant at p>0.05. Trivedi et al., [8] demonstrated that the TPB constructs explained 37 percent of the variance in intention and failed to predict physical activity intention. The main principle of TPB is that intention predicts behavior. This means that recuperating alcoholics have to be motivated in order for them to practice physical activity however it is difficult to assess the true extent of an individual’s motivation. An individual may indicate having the intention to practice physical activity but may never practice it. It could also be due to the perceived barriers that prevent motivated individuals from carrying out their intention. Based on these findings it appeared that only individuals who are motivated were currently engaging in recommended levels of physical activity [17-20].

The use of SEM, although still applied sparsely in physical activity, has the potential to expand knowledge of complex relations among social and behavioral constructs and measured variables. Physical activity experts or other health professionals who wish to use SEM to explore such relations should apply all the steps used in SEM and ensure they have a sample that is sufficient. These steps may help to ensure a more accurate depiction of relations among the variables to more appropriately inform the translation of findings to physical activity-related policies and programs. The researchers should also understand the weakness that hinder use of SEM and appreciate the strength associated with it.

The authors declare that no conflict of interests exists.

All authors were involved with the drafting of the research paper, critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

The authors sincerely thank participants who shared their experiences, and contributed needed information to the study. All those contributed to the success of this study in one way or another are also recognized.

Citation: Lucy A Mutuli, Bukhala P and Nguka G (2021) Assessment of Attitude, Subjective Norm and Perceived Behavioral Control on Physical Activity of Alcoholics Using Structural Equation Modeling, J Alcohol Drug Depend 9:341. doi: 10.35248/ 2329-6488.21.9.341

Received: 01-Apr-2021 Accepted: 14-Apr-2021 Published: 21-Apr-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2329-6488.21.9.341

Copyright: © 2021 Lucy A Mutuli, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.