Anesthesia & Clinical Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-6148

ISSN: 2155-6148

Research Article - (2021)Volume 12, Issue 1

This article evaluates the adoption of an Instrument Retraction Technique (IRT) taught in preclinical local anesthesia to dental students, and its subsequent use in their clinical practice. Immediately following their basic injection technique instruction, first-year students were asked to observe senior students’ technique over a three-week period. During this time, they completed surveys to determine if senior students continue to apply the techniques taught during the first-year course.

The results of the surveys suggest safer techniques taught in preclinical curricula continue to be used during clinical procedures. Successful introduction of IRT during mandibular anesthesia into a dental school curriculum is an option for potential reduction in intraoral needle sticks and should be considered when evaluating local anesthesia curriculum in dental schools. The instruction of dental students should coincide with clinical faculty training and calibration. The authors concluded that further evaluation of the technique should be performed to confirm reduction of risk of Blood borne Exposure (BBE) to clinician without subsequent need for additional anesthesia to patient.

Local anesthesia; Needle stick injury; Blood borne exposures

Dental anesthetic needles are the most common devices involved in Blood Borne Exposure (BBE) incidents involving dental students [1-3]. Injuries may occur during delivery of anesthetic, uncapping and recapping needles, and when disassembling the reusable dental syringe and discarding the needle. A common method of retraction during intraoral anesthesia delivery involves use of a finger to pull mucosa taut after palpating the injection site, especially for mandibular block anesthesia [4-7]. Published studies, and data collected at the authors’ institution show that BBE associated with dental anesthetic needles and intraoral delivery account for as many as 37% of all BBE [3,8-10]. Following a previous article describing the clinical technique in 2016, the authors’ aim in this study was to evaluate if an Instruction Retraction Technique (IRT) was consistently adopted once dental students were treating patients in the clinics. The earlier study showed that learning a modified technique that does not use the operator’s finger for retraction may reduce risk of BBE during intraoral anesthesia delivery. The study also compared information on the patients’ perception of comfort [10].

IRT is an acronym used in minimally invasive dentistry as well as a mandibular block regional block [5,11]. For this article, the author’s define IRT as an instrument technique used in local anesthesia delivery. The technique described by the authors involves using a mouth mirror or Minnesota retractor ® instead of the operator’s fingers for retraction during injection. Fingers are still used to palpate landmarks prior to injection but are replaced with the instrument retraction prior to delivery of dental local anesthesia. The authors’ purpose is to further confirm the adoption of IRT and recognize its application into clinic setting in subsequent years.

The authors’ institution, a private university runs on quarter system and offers a thirty-six-month Doctor of Dental Surgery Degree (DDS) degree. Class sizes are currently 144 for the DDS program. This project received IRB approval (10-41.5 and 15-110) from the institutional review board committee.

Preclinical curriculum

Students participate in a hands-on local anesthesia course in the fourth quarter of first year for DDS students. The curriculum includes basic techniques, and clinical applications of armamentarium. Prior to entering the teaching clinics, students successfully complete a weeklong competency to certify administration of local anesthesia. Techniques learned within the course model a guided behavior for students to apply in their own practice philosophy [12-15]. Emphasis is on identifying anatomical landmarks by finger palpation, both extraorally and intraoral prior to injecting into mucosa, with students switching to mirror retraction just prior to administering anesthesia.

In 2011, the use of instrument retraction in place of finger retraction for the injection procedure was introduced into the pre-clinical course in an effort to reduce BBE associated with intraoral local anesthesia delivery. Intraoral injury from delivery of anesthesia accounted for 37% of reported BBE injuries over a 10 years period at the author’s institution [10].

Faculty involvement

Faculty who were not involved in the preclinical anesthesia course received cross training with ART at annual intervals, which began in 2014. Additionally, to review the adoption of IRT, a survey was developed in 2014 asking first year DDS students to record one observation of a senior dental student in the teaching clinics.

During the observation, a faculty member would verify profound anesthesia via conversation, asking specifically for signs of altered sensation. Ice tests and electronic pulp test were available if the faculty determined it was necessary [16-18]. If a faculty recommended additional anesthetic and/or a different technique this was documented in the comments section of the observation form. Faculty confirmed presence of single student-patient observation, profoundness of anesthesia, incidence of blood borne exposure, and completion of procedure prior to returning the printed observation form for data collection.

Survey observation form

The survey observation form was developed by the Local Anesthesia Course Director with the purpose of determining the level of adoption of IRT in the teaching clinics, and to gather information related to the injection technique applied for the procedures. Observation participation was voluntary however extra credit was given for completion.

The observation form required completion within a specified time frame. The timeframe for observation of senior dental students occurred within three weeks prior to their graduation.

Data collection

During the period of observations, senior students had been in practice in teaching clinics for about seventy weeks. Observation forms recorded the type of clinical procedure; retraction technique, injection type, and whether additional anesthesia was necessary to achieve profound anesthesia (Supplementary Figure 1)

Authors organized data from observation forms according to injection techniques; infiltrations, maxillary block, and mandibular block. Mandibular block injections were identified as a combination of Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block (IANB) with buccal and lingual injections, or Gow-Gates technique [4,6,19]. Instrument retraction classifications included use of mouth mirror or Minnesota retractor®. The author’s focused on collecting data associated with mandibular block anesthesia to verify adoption of IRT. Observations were collected in 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017, and were organized by the types of injections. The 2016 data was excluded in this study because a change in faculty may have led to lack of calibration. This was resolved by 2017.

Observation forms that were incomplete (no faculty signature or date), unclear (circled answer without specified comment), or were unreadable due to poor handwriting were not included in the results. The authors also reviewed data from the institution’s BBE database to determine the rate of injuries related to intraoral needle sticks during the period of this study. The institution requires completion of a BBE report form for each exposure. The electronic form is completed and housed in a web-based database, allowing for review of data for specific criteria, such as type of injury, device involved, extraoral or intraoral, and use of safety devices. Data can be sorted by teaching clinic locations, class year of student, date, procedure completed, and action taken. All investigators analyzed BBE data for the purposes of this study independently to reduce the risk of error or bias.

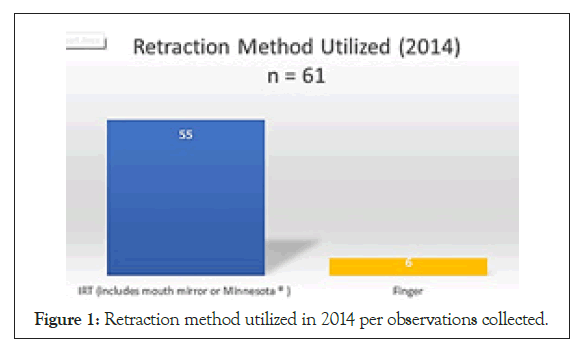

In 2014, one hundred twenty-three survey observation forms were collected. Sixty-one met the inclusion criteria for use in this study. Of the sixty-one recorded, fifty-five applied IRT and six used a finger retraction method (Figure 1). No intraoral needle stick injuries and no failed anesthesia were reported on any of observations forms collected. The BBE reports confirmed no associated intraoral needle stick injury was reported during the observation timeframe.

Figure 1: Retraction method utilized in 2014 per observations collected.

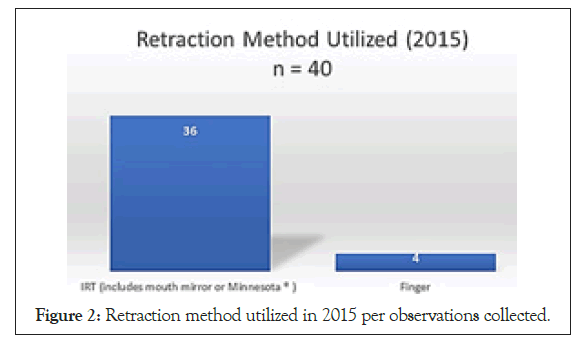

In 2015, one hundred twenty-one survey observation forms were collected. Forty met the inclusion criteria for use in this study. Of the forty recorded, thirty-six used IRT and four used the finger retraction method (Figure 2). No intraoral needle stick injuries and no failed anesthesia were reported on any of observations forms collected. The BBE reports confirmed that no associated intraoral needle stick injury was reported during the observation timeframe.

Figure 2: Retraction method utilized in 2015 per observations collected.

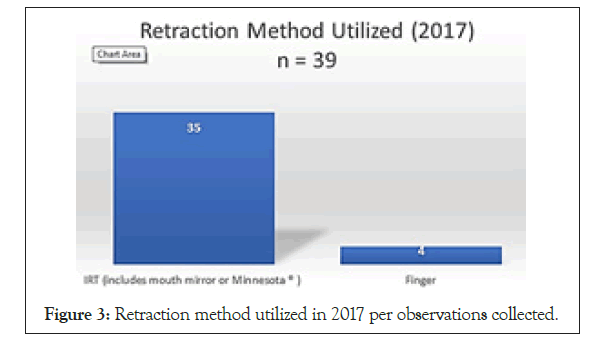

In 2017, eighty-four survey observation forms were collected. Thirty- nine injections met the inclusion criteria for use in this study. Of the thirty-nine recorded, thirty-five used IRT and four used finger retraction (Figure 3). No intraoral needle stick injuries and failed anesthesia were reported on any of observations forms collected. The BBE reports confirmed that no associated intraoral needle stick injuries were reported during the observation timeframe.

Figure 3: Retraction method utilized in 2017 per observations collected.

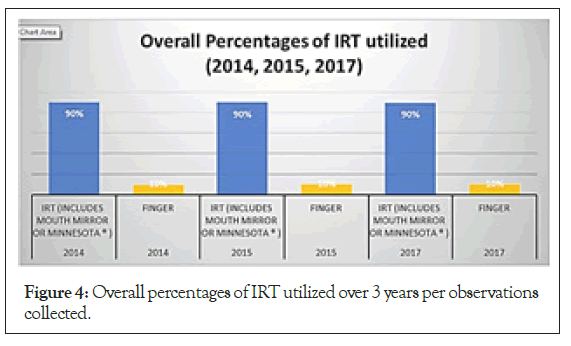

Combining years 2014, 2015, and 2017, one hundred forty injections were eligible for this investigation. From the one hundred forty injections meeting the inclusion criteria, one hundred twentysix (90%) utilized ART and fourteen (10%) utilized the finger retraction method (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Overall percentages of IRT utilized over 3 years per observations collected.

The impetus for IRT adoption was the need to take action to reduce needle sticks that result in BBE, first recommended internally at the authors’ institution in 2011. In March 2014, the American Student Dental Association (ASDA) House of Delegates proposed “a needle stick policy to provide increased protection for students potentially exposed to infectious diseases during the course of treatment both in school and at volunteer events.” The resolution called for the council on Professional Issues to schools to evaluate the need for, and if necessary, create a needle stick policy and report back to the 2015 House of Delegates. ASDA.NET 2015 Adopted Resolutions for recommendations [20].

One way to begin the movement of safer practices is to implement the change in a learning environment [10,21,22]. The risk of intraoral BBE due to needle sticks has been clearly identified in dentistry [3,23]. Reevaluating current retraction methods and educating practitioners on preventative methods has been an ongoing effort [24-26].

Observations reported 90% (2014), 90% (2015), and 90% (2017) of anesthesia procedures utilized IRT. Overall observations confirm widespread adoption of IRT among dental students at this institution into teaching clinics. Further, results address the adoption of IRT applied towards the safer practice as no intraoral needle sticks were identified. Results from clinical observations suggest that safer techniques taught in preclinical curricula can be successfully implemented in the clinical setting.

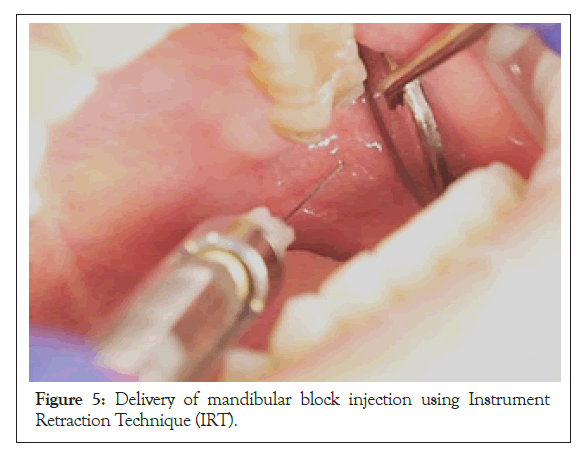

Oral health care providers may struggle with utilization of IRT for mandibular block injections. According to the scientific dental literature, Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block (IANB) average success ranges from 48%-63%; this guided the authors to focus on mandibular block injections [4,12,27,28]. The method of pedagogy described in this study is valuable not just for the institution but also for consideration of implementation into professional practice [29,30]. This, along with the reduction in intraoral needle sticks noted in the previous study, indicates that adoption of IRT may be a safer alternative that does not have a negative impact on procedure [3,10,26] (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Delivery of mandibular block injection using Instrument Retraction Technique (IRT).

Limitations to the study include limited time frame, inequality of yearly data collection from teaching clinics within the author’s institution, consistency of injection technique administered, small sample size, and changes of faculty within the teaching clinics.

Performing the observations in a single three-week period does not give insight into whether use of IRT occurs consistently for each student yearlong. Although, the results did not see an inordinate amount of anesthesia failures, data collected was from one U.S. dental school and the results may not be generalized to other dental schools.

Specifics to recording could have been more detailed. In particular, achievement of anesthesia and completion of the procedure as documented by supervising faculty could have been better recognized.

Lastly, the administration of LA may cause pain and anxiety in patients [31,32]. Pain and anxiety of patients before, during, or after the procedures was not recorded.

The investigators continue to track the adoption of IRT and have included these details in the surveys for subsequent years. The authors suggest further study, continued tracking of the implementation of IRT for further cohorts with increase in sample sizes. Minimal literature exists to encourage alternative methods of retraction, rather most literature details efficacy of injection techniques, anesthetic agents, and additional armamentarium for pain management [10,14,20,26,33].

Further evaluation of the IRT should be performed to confirm reduction of risk of BBE to clinicians using this technique. Additionally, adoption of IRT, specifically for mandibular block anesthesia, may be successfully implemented and considered when evaluating local anesthesia curriculum in dental education. Instruction of dental students should be combined with clinical faculty training and calibration [34].

This evaluation confirms the adoption of an Instrument Technique of Retraction (IRT) taught in preclinical local anesthesia can be successfully adopted into clinical practice.

Implementation of instrument retraction, such as IRT, during delivery of a dental injection within the local anesthesia course curriculum is valuable to students’ learning and addresses a concern raised by student organizations. If we teach the next generation of oral health care providers to administer local anesthesia using a safer alternative technique, we may be moving towards safer practices in general. Techniques learned in dental school provide the foundation for lifetime practice as a competent oral healthcare professional. Finally, IRT may also be of interest to those invested in reviewing or creating comprehensive needle stick policies.

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of Michael Interrante, Dr. Jasmine Yee and Dr. Rigel Smart, and Dr. Om Suchak for the photography included. The authors also want to thank the University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry.

Citation: Brady M, Woo D, Cuny E, Alvear Fa B (2021) Adoption of IRT: An Instrument Retraction Technique in Local Anesthesia Delivery. J Anesth Clin Res. 12: 986

Received: 28-Dec-2020 Accepted: 11-Jan-2021 Published: 18-Jan-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2155-6148.21.12.986

Copyright: © 2021 Brady M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.