Journal of Clinical & Experimental Dermatology Research

Open Access

ISSN: 2155-9554

ISSN: 2155-9554

Case Report - (2019)Volume 10, Issue 2

Cutaneous leiomyomas are rare, benign smooth muscle tumors of the skin, with autosomal dominant but incomplete penetrance. hereditary leiomyomatosis syndrome consists of the triad of uterine leiomyomas, cutaneous leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Here, we present a case of previously healthy man with no past medical nor family medical history who seeked medical advice for asymptomatic skin lesions of 2 month durations. Upon examination, patient was found to have leiomyomas with renal cell cancer. Therefore, it is of a great importance to recognize these skin lesions for early detection of devastating associated tumors.

Hereditary leiomyomatosis; Leiomyoma; Reed syndrome

Cutaneous leiomyomas are a rare, benign smooth muscle tumors of the skin, subcategorized based on the origin of the smooth muscle within the tumor. They are classified as follows: piloleiomyomas, which originate from the erector pili; genital leiomyomas, which originate from the dartos muscle of the skin in the genital area; and angioleiomyomas, which originate from the smooth muscle of the vasculature. Most pilar leiomyomas occur singly, but can occur as multiple lesions. Reed's syndrome, also known as multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis (MCUL: OMIM 150800) and hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC: OMIM 605839), is a condition inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance, consisting of multiple pilar leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas and, rarely, leiomyosarcomas, in the multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis (MCUL) syndrome and in association with renal cell carcinoma in the hereditary leiomyomatosis renal cell cancer (HLRCC) syndrome. The diagnosis is made by the presence of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with at least one histologically confirmed leiomyoma or by a single leiomyoma in the presence of a positive family history of HLRCC [1,2]. Here, we present a healthy man who presented for esthetic consultation for multiple asymptomatic lesions. Upon further investigation, he was diagnosed with leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Therefore, it is of a great importance to recognize these skin lesions for early detection of devastating associated tumors.

26-year-old male patient, previously healthy, presented to our clinic for asymptomatic upper and lower limbs lesions of two months’ duration. The patient reported being bothered esthetically from the abundance and the appearance of the lesions especially that they were affecting his work socially and professionally.

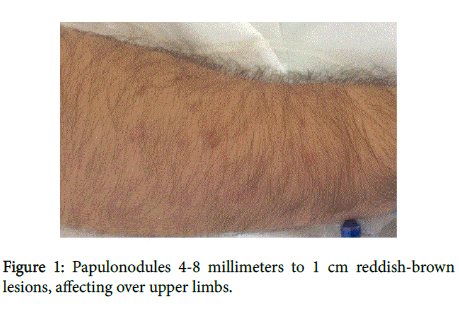

On physical examination, he had more than 100 firm, papulonodules fixed to the skin, ranging in size from 4-8 millimeters to 1 cm, reddish-brown in color, affecting only his upper and lower limbs (Figures 1 and 2). No other sites were affected and he had no mucosal lesions. There was no increase in erythema or edema when rubbed.

Figure 1: Papulonodules 4-8 millimeters to 1 cm reddish-brown lesions, affecting over upper limbs.

Figure 2: Papulonodules 4-8 millimeters to 1 cm reddish-brown lesions, affecting over lower limbs.

His past medical history was negative for skin cancers and his past surgical history was negative. There was no family history of skin problems and the generalized physical examination was normal. Our differential diagnosis included leiomyoma, dermatofibroma and schwannoma.

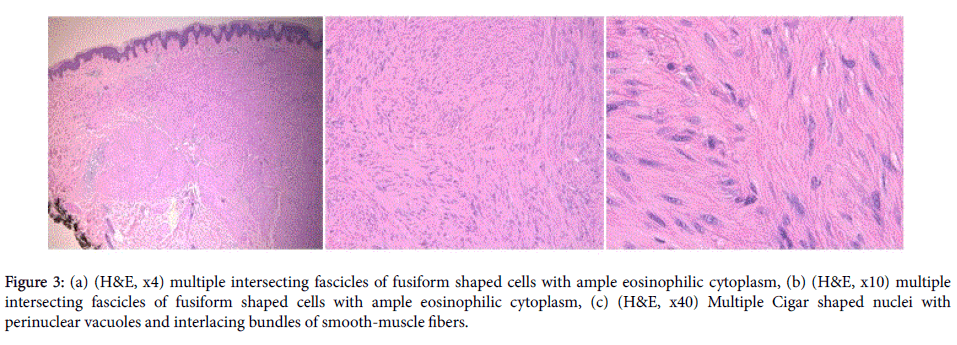

Histopathological examination from an excisional biopsy revealed a dermal nodule made up of multiple intersecting fascicles of fusiform shaped cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Multiple Cigar shaped nuclei with perinuclear vacuoles and interlacing bundles of smoothmuscle fibers were also seen (Figures 3a-3c). All the features were suggestive of cutaneous piloleiomyomas.

Figure 3: (a) (H&E, x4) multiple intersecting fascicles of fusiform shaped cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, (b) (H&E, x10) multiple intersecting fascicles of fusiform shaped cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, (c) (H&E, x40) Multiple Cigar shaped nuclei with perinuclear vacuoles and interlacing bundles of smooth-muscle fibers.

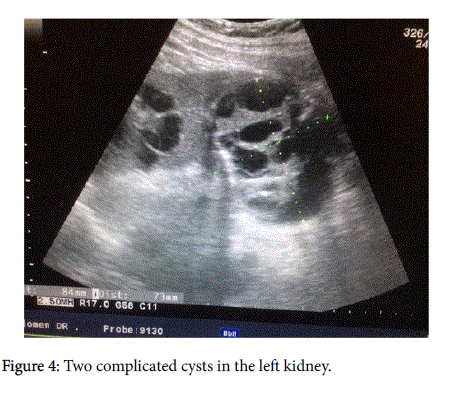

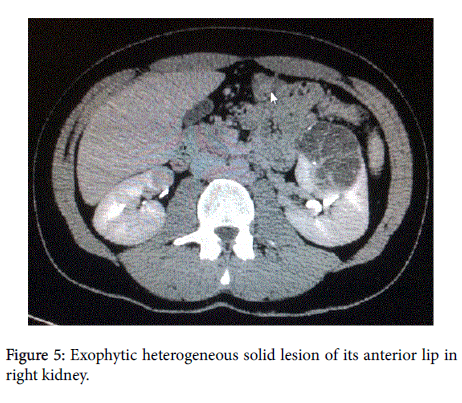

And by knowing that cutaneous piloleiomyomas can be associated with some syndromes, a blood workup was ordered for evaluation of complete blood count (CBC) and biochemistry (BUN, creatinine and electrolytes) as well as urine analysis and urine cytology. All the laboratory workup came up as normal. Also, an ultrasound of the kidneys was done which showed two complicated cysts in the left kidney, one in the upper pole with the cysts showing echogenic content and calcifications and one in the lower pole (Figure 4). Therefore, a CT scan was done to assess the complicated cysts in the left kidney and it showed two large malignant multi-cystic masses in the left kidney with thick septations, calcifications and soft tissue components (Bosniak IV). The right kidney showed also an exophytic heterogeneous solid lesion of its anterior lip (Figure 5). All these findings were highly suggestive of renal carcinoma.

Figure 4: Two complicated cysts in the left kidney.

Figure 5: Exophytic heterogeneous solid lesion of its anterior lip in right kidney.

Patient was scheduled for total left nephrectomy and the pathology showed Clear cell carcinoma of the kidney with no evidence of capsular invasion.

Then, a right partial nephrectomy was done after complete recovery of the first surgery and the biopsy also showed Clear cell carcinoma; which led us to the diagnosis of Hereditary Leiomyomatosis Renal Cell Cancer (HLRCC) or what is known as REED syndrome. Two months after recovery, the patient came for follow-up with a quasi-disappearance of the lesions with only post inflammatory hyperpigmentation remaining.

Topical and systemic antibiotics have been commonly since a very long time for the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. They improve acne lesions by inhibiting the growth of C. acnes and⁄or their production of pro-inflammatory mediators [3,4]. Although C. acnes is known to be sensitive to a wide range of antibiotic classes including clindamycin, macrolides, and cyclines, however the resistant strains of C. acnes are gradually increasing worldwide with the rampant use of antibiotics and the patterns vary from one region to another [7,9,12-14,18-22].

Our study showed a C. acnes prevalence of 60% which was comparable to the isolation rates of 66.4% by a previous community based study from Singapore in 2007but lesser than a Hong Kong based study (77.4%) and one other from India (65%) [12,18,20]. Much higher prevalence rates were seen in a multicentric study from Europe (94%) [9]. The previous use of antibiotics among acne patients in our study was 49.4% which was comparable with the 48% in the European study [9] but far less than the Hong Kong study [18]. The most common antibiotic used in our study was doxycycline which contrasts with the other two studies mentioned above where clindamycin and erythromycin were the most common antibiotics used [12,18].

There is an evidence for an overall increase in the use of antibiotics for acne in Singapore. The previous use of antibiotics among patients harboring C. acnes was 25.2% in the previous community study as compared to 49.4% in our study [1]. With the overall increase in the use of antibiotics among acne patients, the percentage of acne patients carrying C. acnes strains resistant to these antibiotics is increasing worldwide and vary from one region to another [7,9,13,14,18-22]. In Singapore, a study carried out in 1999, the antibiotic resistance rate was 11% [13]. In that study, no resistant strains were identified in patients who had not received any antibiotics. Another study in 2007, antibiotic-resistant strains of C. acnes increased to 14.9 %, of which, 42% had received antibiotic treatment for acne [12]. Our study showed a resistance rate of 28.5% and the antibiotic use among the patients harboring resistant strains has further increased to 59.7% in our study. However, as compared to other studies, the resistance rates in Singapore are less as compared to 54.8% in Hong Kong and Europe (50.8% to 93.6%) [9,18]. Looking at the high proportion of antibiotic use (92.7%) in the Hong Kong study as compared to 49.4% in our study, the results can be justified. Why resistance rates in Europe was far more than our study, despite having similar rates of previous antibiotic use is not understood. Probably, the increase in resistant strains in the European study could be in part due to the transfer of resistant strains from close contacts.

Similar to our study, erythromycin and clindamycin were the commonest to develop antibiotic resistance in many previous studies [9,12,13,23-27]. These studies also showed combined resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin. Cross-resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin was a common finding in our study. The mechanism underlying erythromycin and clindamycin resistance was elucidated by Ross et al. [28], who identified four phenotypes with cross sensitivity to macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin B (MLS) antibiotics. Genetic mutations occur mainly in 23S rRNA, and strains that possess the erm (X) resistance gene are highly resistant to MLS antibiotics. Minocycline resistant strains were detected in Singapore in 2007and the percentage resistance since then (1.7%) has remained constant in our study (1.7%) indicating the lesser propensity of minocycline to develop resistance or an overall reduced frequency of its use in our patients (4.7%) [12]. We could not find any significant difference in the acne severity between patients harboring resistant strains versus those who had sensitive strains of C. acnes . Toyne et al. [29] had also found in their cohort that the severity of acne was not linked to resistance.

Patients harboring resistant strains of C. acnes were more likely to have received oral erythromycin and oral minocycline in our study. These patients were also more likely to have received topical clindamycin though the difference failed to reach statistical significance (P=0.1). These findings are similar to the European study by Ross et al. [9] which concluded that bacterial resistance is promoted by a previous treatment with MLS antibiotic (azithromycin, erythromycin, clindamycin) and use of topical clindamycin drives resistance to itself and erythromycin. This study also demonstrated that resistance to tetracyclines was more likely when the treatment regimen included any tetracycline, and minocycline was the as the driver of resistance to tetracyclines. On the other hand, Zandi et al. [22] and Sardana et al. [20] did not find any difference any difference in treatment history between resistant and sensitive strains. While Zandi et al. attributed it to shorter period of antibiotic therapy, Sardana et al. attributed the lack of correlation to the mutation based resistant strains which tend to persist.

When patients with sensitive strains were observed over the 4 month follow up period, approximately double the proportion were resistant at 4 months than at 2 months (9.6% vs. 4.5%) [30,31]. Almost all of these subjects were on one or other antibiotic at the time of specimen collection. Minocycline was the only antibiotic which was used significantly more by the resistant group supporting the finding by Ross et al. [9] that minocycline serves a selective agent and the driver of resistance.

Although the most common antibiotics to have developed resistance were erythromycin and clindamycin, there was no difference with regards to current antibiotic use of MLS antibiotics between the resistant and sensitive groups. This can be attributed to the short follow up period of 4 months in our study. Evidence exists that the frequency of isolation of resistant strains increases with the duration of antibiotics and in antibiotic naïve patients resistant strains begin to emerge mostly after 12 to 24 weeks of therapy [14,32]. It is also possible that the resistant isolates in many of these patients could have been obtained from their close contacts harboring resistant strains [9].

In patients who turned resistant at visit 3 from negative culture results at baseline, doxycycline appeared to have a statistically significant decreased usage than those with sensitive strains. It is important to note that doxycycline, despite being used very commonly had a lesser propensity to develop resistance. This could be attributed to the fact that topical cyclines are not used for treatment in acne which could be the reason for the reduced prevalence of cycline resistant strains.

Treatments for the isolated cutaneous leiomyomas are largely dictated by the patient’s degree of skin discomfort. Options include surgical excision, cryoablation, CO2 laser ablation and medications such as calcium channel blockers or alpha blockers. In addition, botulinum toxin has also been shown to decrease the intensity & frequency of the pain caused by the leiomyomas.

As for the hereditary leiomyomas, studies have shown that early hysterectomy or nephrectomy may be the treatment of choice because of their aggressive nature, as we have seen in our patient.

Citation: Bachour J, Sakkal M, Bedoyan Z, Ammoury A (2019) A Case Report of Hereditary Leiomyomatosis to Increase Awareness of the Correlation between Cutaneous Lesions and RCC. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res 10: 489. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000489

Received: 27-Jan-2019 Accepted: 04-Mar-2019 Published: 11-Mar-2019

Copyright: © 2019 Bachour J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.