Journal of Depression and Anxiety

Open Access

ISSN: 2167-1044

ISSN: 2167-1044

Research - (2020)

Background: Street adolescent are the most marginalized group of population with a high risk of mental health and prolong exposure to psychosocial distress results in developing a compromised quality of life, healthy socialization, and overall development. Despite this fact, little attention is given to the psychosocial wellbeing of street children in Africa practically in Ethiopia. This study aimed to assess the psychosocial distress among street adolescents in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Research Methodology: Community-based mixed cross-sectional study was conducted among 422 participants, and 4 focused group discussants. Study participants were selected conveniently in the quantitative part and purposively in the qualitative part. A pre-tested, semi-structured, interviewer-administered, and focused group discussion guide questionnaire was used to collect the data.

Result: About 223 (55.1%) street adolescents were psychosocially distressed. Bing in the age range of 16-18 years old [(AOR=3.9, 95% CI: (1.6, 9.11)], meal availability once per day [(AOR=4.46, 95% CI: (1.83, 10.85)], being sexually abused [(AOR=2.36, 95% CI: (1.1, 4.95)], meal availability twice per day [(AOR=4.24, 95% CI: (1.91, 9.44)], being physically abused [AOR= 2.43, 95% CI: (1.05, 5.63)], and low income status (parents) [(AOR=2.6, 95% CI: (1.59, 4.24)] were significantly associated factors.

Conclusion: More than half of the participants have psychosocially distressed. Establishing and implementing local mental health policies and programs for street children through collaborative efforts with the government and nongovernment sectors to bring them into the mainstream of the society. Family reintegration and strengthen the legal systems to minimize violence are also important measures to decrease the problem.

Psychosocial distress; Street; Adolescent; Tigray; Ethiopia

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; FGD: Focused Group Discussion; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; PTSD: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder; STI: Sexually Transmitted Infection

Psychosocial distress refers to unpleasant experiences of psychological, social, and/or spiritual symptoms that could individuals make it difficult to cope with their usual daily life [1]. Adolescence is a person categorized in the age group of 10-19 years old and this age is a phase when enormous physical, psychological, and social change occurs [2]. Street Adolescents are children living in the street and they are the most valuable resource of the society [3]. Children with neglect to any dimension of psychosocial wellbeing like physical, social, psychological, and spiritual have compromised social life with others, mental health, and overall development [4].

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has defined street children as those who are out from families living on the streets (children of street families), those who spend a portion or majority of their time on the street while returning home to a family at night (children on the street), those who spend both days and nights on the street with limited or no family contact (children of the street) [5]. Predominantly, street children mainly adolescents are the most marginalized section of the population and disposed to problems of psychosocial wellbeing [4].

About one-fifth (1.2 billion) of the world population are adolescents, and 85% of them are in the developing world [2]. An estimated of 120-150 million street children live in the world. Out of this number, 50% live in South America, 25% in Asia, and 25% in Africa [3]. Mental health problems affect all segments of the people particularly vulnerable groups of the population [6]. One out of four people suffered from distress at some point in their lives, and 10–20% of adolescents were suffered from mental distress [7,8]. In Asia, a meta-analysis study revealed that 45% to 61.4% of street children suffered from mental distress and 6.3% attempted suicide [8,9].

In African and Sub-Saharan African countries a large number of street children were suffered from depression, anxiety, hopelessness, and suicide [10]. A systematic review in Sub-Saharan African revealed that a significant number of children were faced with 14.3% of psychosocial distress, 15% depression, 17.8% posttraumatic stress disorder, and 6.8% of low self-esteem [11,12].

Ethiopia is one of the developing countries with its urban areas are challenged by the growing intensity of street children [13]. Evidence showed that the overall numbers of children on the streets of Ethiopian cities are estimated to be 150,000, and over 50% of street-connected children were psychosocially deprived [14,15]. In the absence of early intervention for street children and prolonged exposure, street life results in severe mental distress, behavioral disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social isolation, poor school performance, and suicide [9]. Besides, to cope with their difficulties, street children used risky behaviors like being aggressive and fighting, smoking, chowing chat, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted infection (STI) which lead further to mental distress [9,16]. Children live inadequately on the street with full of child vulnerability and deprivation of basic rights such as food, shelter, cloth, hygiene, education, and health service. They are also faced with problems of abuse, torture, violence, and exploitation [16,17].

Existed studies revealed that family conflict, orphanhood, nonbiological parents, child abuse, survival work, educational status, and meal availability were among the factors for children which makes them vulnerable [4,18,19]. Efforts on improving child and adolescent mental health policy initiatives in Africa and Sub- Saharan African countries were neglected. Different studies also agreed on solutions that have tried to solve the problem of street children were very limited in scope and only focused on the curative approach and short term needs of the child [20-22].

Most countries of the world have established mental health strategy to address the problems of mental health, however, they have lacked standalone mental health policy and inadequate budgets allocated to the problem. Besides, efforts at improving child health and devolvement initiatives in Africa and Sub-Saharan African countries mainly focused on the physical health of children [22,23]. Despite the fact, the overall development of the street child and the issue of psychosocial wellbeing has given limited attention in Ethiopia, particularly in the study area. Thus, this study aimed to assess the magnitude of psychosocial distress among street adolescents in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Study area and period

The study was conducted in the zonal towns of Tigray from January 7 to February 12, 2020. Tigray is located in the north part of Ethiopia. Mekelle is the capital city of Tigray, which is 783 Km away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. It has six administrating zones and one city administration and it also has more than 6 million inhabitants [14]. According to the Tigray Labor and Association Affaires Office’s report, there were about 6542 street children in Tigray regional state [24].

Study design

Community based mixed-cross sectional study was conducted.

Population

All street children living in Zonal Towns of Tigray were the source population. All adolescent street children (10-19 years old) living in selected Zonal Towns of Tigray consisted of the study population. All purposively selected street adolescents were a member of the focused group discussion for the qualitative part. Children who were unable to communicate due to medical problems were excluded.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula n = (Zα/2)2 p (1-p)/d2) with the assumption of 95% confidence interval, 5% marginal error, 10% non-response rate, and the prevalence of psychosocial distress (P = 0.51) from a previous similar study done in Ethiopia [21]. It gives 384 and by adding the non-response rate (384+384*10%), then the final sample size for this study was 422. The sample size for focused group discussions (FGD) was determined by the ideal saturation.

For the sampling procedure, there were six zonal towns, and one administrative city in Tigray regional state. First, three zonal towns and the administrative city were selected by the lottery method. Population proportion allocation to the sample size was done to each randomly selected zonal town. Finally, street children with the age range of 10-19 years old who live in the selected towns, and administrative city during the data collection period were interviewed using a convenience sampling technique until the required sample size meet. In the qualitative part, the number of focus group discussions was determined by saturation of ideas. A total of 4 focused group discussions comprising of 40 discussants (30 male and 10 female) participated in this study.

Operational definition

Psychosocial distress: This was measured by using the 12 General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) items. Participants who scored equal and above the mean of the GHQ-12 score were considered as psychosocial distressed and those who scored below the mean were considered as no psychosocial distressed [25,26].

Street children: Children aged 10-19 years old who come to the street to work, escape from their families, and children from street parents and stay on the street with their parents [27,28].

Physical abuse: At least one act or treat of slapped, pushed, shoved, pulled, throw something that could hurt, choked, burning on purpose, hit the abdomen with a fist or with something else and if a gun, knife other materials used by anyone against the child [29].

Sexual abuse: Report of at least one act or threat of forced sex, touching sexual organs and had sexual intercourse when she/he did not want [30].

Data collection tool and procedure

Pretested, semi-structured, interviewer-administered General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was used to measure the psychosocial distress among the street adolescents of Zonal Towns of Tigray. This measurement tool was standardized, designed, and validated by the WHO to measure and understand the psychosocial distress and mental health status of an individual that was used by South American, Asian, and African countries including Ethiopia [31,32]. The questioner consisted of socio-demographic and other related characteristics of street adolescents and their parents. It also consists of 12 items of GHQ-12, how they felt recently on a range of items including able to concentrate on what respondents are doing, sleep due to worry, playing a useful part in their life, capable of making decisions, constantly under strain, overcome difficulties, able to enjoy normal day-to-day activities, able to face up to problems, feeling unhappy or depressed, losing self-confidence, thinking of self as a worthless person, feeling reasonably happy. Each item has 4 response choices (not at all, no more than usual, rather more than usual, and much more than usual) scoring as 0, 1, 2, and 3 respectively [32].

For the qualitative part, an open-ended, unstructured, and flexible discussion guide was prepared based on the objective of the study. It was first prepared in English and translated into the local language (Tigrigna) by a language expert. Focused group discussion guides and the audio (tape record) was used while participants discuss the issue. Before the data collection, contacts with the social workers and key informants such as counselors and NGOs that have direct contact with the street children was performed to have full information to conduct a survey and identify where they often live. Data were collected by six trained data collectors, two of them had a first degree in psychology, two had a first degree in sociology and the remaining two were psychiatric nurses. The purpose of the study was explained to the participants and voluntariness was assured.

Data quality assurance

The questionnaire was standardized and prepared first in English then translated to the local language Tigrigna, and then translated back to English to maintain its consistency. The pretest was done in 5% of the participants in the non-selected study area (Adwa Town), and the correction was taken accordingly. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for two days before the actual data collection begin. Supervision and close follow up was done throughout the data collection period. For the qualitative part, one trained female research assistants (a social worker) moderated the female group activities while the principal investigator and male psychologist guided the male groups. One female and one male assistant from the team organized the FGDs and handled tape recordings. The discussions were tape-recorded and all observations made were recorded as field notes. The discussions were conducted in a quiet place to encourage free discussion without any threats and each lasted for 40–60 minutes.

Data analysis

First, data were coded, checked, and entered into Epi data version 4.1 then exported to SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistical analyses such as simple frequencies, measures of central tendency, and measures of variability were used to describe the characteristics of participants and their parents. Information was presented using narratives, frequencies, summary measures, tables, and figures. Binary logistic regression was done and variables with p-value <2.5 were the candidate to the final model. Collinearity was checked using standard error. Hosmer–Lemeshow and Omnibus tests were done to test model goodness of fit. A multi-variable analysis test was done to control possible confounders and odds ratios with 95% confidence interval were used to show the strength and direction of the associations and variables with a p-value <0.05 was declared as statistically significant. For the qualitative part, data obtained from the FGD were transcribed and translated into the English language first. Then, the contents of the group discussion guide were grouped under selected themes based on questionnaire guides and were analyzed using thematic analysis. Then finally, the finding was presented narratively triangulated with the quantitative results. Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was secured from Mekelle University College of Health and Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board (ERC 1508/2020). A letter of permission was obtained from Tigray Labor and Association Affaires Office and each selected study town and Mekele city. Informed, voluntary, and oral consent was obtained from each participant after clearly informing them about the purpose, risk, and benefit of the study. Participants were informed that they can withdraw the interview at any time which is not comfortable for them.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

From a total of 422 participants, 405 street children were interviewed making a response rate of 95.9%. The mean age of the respondents was 15 (SD±2) years old. More than half, 216 (53.3%) respondents were in the age range of 16-19 years old and one hundred twentyfive (30.9%) were in the age range of 13-15 years old. About 373 (93.6%) were males, 300 (74.1%) of participants comes from the rural areas before their street life, and 367 (90.6%) were Tigray in their ethnicity. About 382 (94.3%) were orthodox in their religion. More than half, 212 (52.3%) of respondents' parents were living together, 93 (23%) were orphaned and 310 (77%) of participant parents alive. About 180 (44.4%) respondents were completed in primary school (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics among street adolescents in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, 2020 (N=405), January 7 to February 12, 2020.

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year) | 10-12 | 64 | 15.6 |

| 13-15 | 125 | 30.9 | |

| 16-19 | 216 | 53.3 | |

| Sex | Male | 379 | 93.6 |

| Female | 26 | 6.4 | |

| Origin of place (residence) | Urban | 105 | 25.9 |

| Rural | 300 | 74.1 | |

| Ethnicity | Tigray | 367 | 90.6 |

| Others* | 38 | 9.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 382 | 94.3 |

| Muslim | 23 | 3.2 | |

| Others** | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Educational Status | No formal education | 159 | 39.3 |

| Primary school | 180 | 44.4 | |

| Secondary school and above | 65 | 6.2 | |

| Marital status (Parent) | Live together | 212 | 52.3 |

| Widowed | 82 | 43.4 | |

| Divorced/separated | 111 | 23.2 | |

| Orphan status | Non-orphaned | 312 | 77.0 |

| Orphaned | 93 | 23 | |

| Income status (parents) | Good Poor |

214 191 |

52.8 47.2 |

| Household head (parents’ house) | Father | 233 | 57.5 |

| Mother | 93 | 23.0 | |

| Child | 65 | 16.0 | |

| Other*** | 14 | 3.5 |

*=Amhara, Eritrea, **=Catholic, and Protestant

In this study, participants reported that the source of food for their daily life got through street vending 87 (21.5%), calling passengers 68 (16.8%), begging 67 (16.5%), carrying 65 (16%), shoe shining 43 (10.6%), washing vehicles 23 (5.7), stealing (4.6%), daily laborer (3.9%), handcraft (1.4%) and selling sex for cents (3.9%). About 90 (22.2%) got meal once daily, 388 (95.8%) were not attending school, near to half 200 (49.4%) experienced physical violence, 195 (48%) experienced emotional violence, 100 (25%) experienced sexual violence, 216 (53.3%) reported they use of substances and about 105 (26%) participants had a history of arrest in their street life (Table 2).

Table 2: Behaviors and other related characteristics of street adolescents in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, (N=405). January 7 to February 12, 2020.

| Study variables | Category | Number (%) | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| The usual source of food |

Street vending Calling passengers |

87 68 |

21.5 16.8 |

| Begging | 67 | 16.5 | |

| Shoeshine | 43 | 10.6 | |

| Carrying | 65 | 16 | |

| Meal availability per day | Three times or more | 180 | 44.4 |

| Twice | 135 | 33.3 | |

| Once | 90 | 22.2 | |

| Current school attendance | No | 388 | 95.8 |

| Yes | 17 | 4.2 | |

| Family conflict | No | 152 | 37.5 |

| Yes | 114 | 28 | |

| Physical abuse | No | 205 | 50.6 |

| Yes | 200 | 49.4 | |

| Emotional abuse | No | 210 | 52 |

| Yes | 195 | 48 | |

| Sexual abuse | No | 305 | 75 |

| Yes | 100 | 25 | |

| Substance use | No | 189 | 46 |

| Yes | 216 | 53.3 | |

| History of arrest | No | 300 | 74 |

| Yes | 105 | 26 |

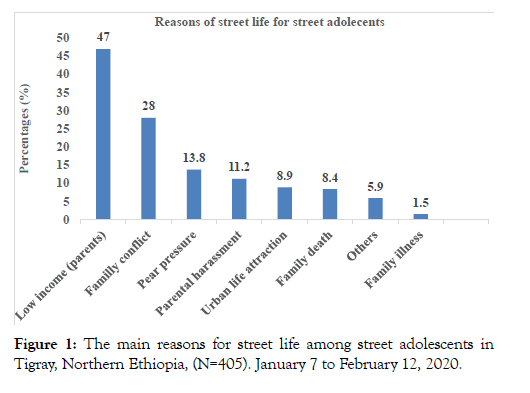

About 191(47%) of participants were in street life because of their parents have low income, participants of the FGD explained poor family background was among the main reasons for most children to the street life (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The main reasons for street life among street adolescents in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, (N=405). January 7 to February 12, 2020.

“……I have been in the street for the last 2 years. I am often visible around Mekelle Romanat and Hawzen Adebabay (name of places/roads in Mekelle city). I am working on the street to help my mother because I have no other alternative to get money. I have no father. My mother is poor and could not raise her 3 children alone….” (17 years old boy, FGD1).

About 8.4% of the study participants reported that parental death was among the reasons for being street children for them (Figure 1). Discussants confirmed that parental death particularly, the death of both parents put many children on the street and this in turn made them vulnerable to distress.

“….Parents are all things for their children... They are a source of food and shelter for their children. Parents fulfill the basic needs of their children. So, being orphaned especially, the death of both parents led many of us to the streets. Streets are places where many suffer arise from leading us to every day to day distress….” (15 years old boy, FGD1).

Twenty-eight percent (28.1%) of the study participants left their home because of disagreement with or within the family, and 8.1% of them were in street life because of family breakdown (Figure 1). Family breakdown due to divorce and death of one or both parents were identified as one principal reason that exposes children to street life.

“…….It is upsetting to push and work on the street because of parental divorce. It is very difficult to live in a home where there is no mother or father with you to prepare food and to fulfill other basic needs…..” (18 years old boy, FGD1).

The participants also reported that they chose street life due to peer pressure 56 (13.8%), parental harassment 45 (11.2%), urban life attraction 36 (8.9%), family illness 6 (1.5%), and about 24 (5.9%) were reported they chose street life due to other reasons (Figure 1).

About 35.7% of the study participants reported that they were sleeping at the veranda (in the road) and 30.4% were sleeping at home with their families. About 279 (68.9%) participants were faced with at least one type of physical, verbal, and/or sexual abuse. Discussants revealed that violence was a common problem for street children. Females were raped, forced to kiss, touching their private part of their body and males were victims of an attempt of penetration when sleeping by their friends and asking for samesex practice. Insulting, intimidation, hitting and beaten by police, street adults, and the community was also among the violent acts illustrated by discussants.

“I was sleeping at night in a rental house with adult street children I am young in the age of all we sleep on the floor without night cloth then I walk up from my sleep when one adult street trying to undress my trouser then I shouted and insulted him then the owner immediately came and asked why I was shouting and I told him what happened but the child insisted that he was doing it unconsciously in his dream and then noticed me and warned me not to disturb again.”(14 years old boy, FGD2).

“…..Life on the street is very hard. Many times I used to get beaten by police for no reason. Sometimes also older street boys beat us for no reason and snatch our clothes and money. They also frighten us without any reason and steal what we have and generally, for me live in the street is miserable and with no hope…..” (18 years old boy, FGD2).

About 216 (53.3%) of the study participants have used substances, and out of this number, 28% of them were cigarette smokers. Most of the discussants revealed that street children used cigarette smoking, chat chewing, alcohol, shisha, hashish, and benzoin sniffing (Table 2).

“The street is a harsh environment with full of stressors. I know taking any addictive substance has been a bad effect on health but I smoke cigarettes because I think it helps me to cope with the stress of living on the streets. I and my friends love drinking, smoking, and having fun at the night clubs. We also sniff benzoin because this helps us to sleep and spend the day sleeping and we accessed the benzoin easily from cars and taxis. The Benzoin serves as alcohol because it losses our consciousness and we become very happy and joyful and we forget to think about other challenges in our life since we accessed in the road, garbage’s, and in-car washes” (16 and 14 years old boys, FGD1).

“……Hunger is one of the worst and not forgettable events of every day for us. No one can give us daily bread unless we worked on the street and got money. But if one of our friends gets the money we never use that money privately. If we have no money to buy remnant food, we buy benzene or mastish, and we sniff it. Soon we feel free of hunger and feeling energetic even when we no got food.” (17 years old boy, FGD3)

The magnitude of psychosocial distress

Among 405 total participants, about 223 [55.1%, 95% CI: (51, 61)] were psychosocial distressed (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Psychosocial distress and associated factors among street adolescents in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, January 7 to February 12, 2020.

Factors associated with psychosocial distress

In the Bivariate analysis age, place where they came, meal availability, violence status, parent’s income status, and history of arrest were significantly associated factors. In the final model (multivariate regression), being in the age group of 16-19, meal availability once per day, being physically abused, meal availability twice per day, being from poor parents, being sexually abused were significantly associated factors with psychosocial distress (Table 3).

Table 3: Factors significantly associated with psychosocial distress among street adolescents in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, (N=405), January 7 to February 12, 2020.

| Characteristics | Categories | Psychosocial distress | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) | No (%) | ||||

| Age (Year) | 16-19 | 135 (62.5) | 81 (37.5) | 2.28 (1.29, 4.02) | 4.79 (1.8, 12.1)** |

| 13-15 | 61 (48.8) | 64 (51.2) | 1.3 (0.71, 2.39) | 2.15 (0.90, 5.10) | |

| 10-12 | 27 (42.2) | 37 (57.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Origin of place | Rural | 169 (58.9) | 118 (41.1) | 1.69 (1.1, 2.6) | 1.0 (0.55, 1.81) |

| Urban | 54 (45.8) | 64 (54.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | Amhara | 10 (43.5) | 13 (56.5) | 0.59 (0.25, 1.39) | 0.60 (0.22, 1.61) |

| Eritrea | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | 0.51 (0.18, 1.47) | 0.57 (0.15, 2.19) | |

| Tigray | 207 (56.4) | 160 (43.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Educational level | No formal | 76 (47.5) | 84 (52.5) | 0.643 (0.359, 1.15) | 0.46 (0.21, 1.03) |

| Primary school | 109 (60.6) | 71 (39.4) | 1.091 (0.613, 1.94) | 1.73 (0.80, 3.76) | |

| Secondary school | 38 (58.5) | 27 (41.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Marital status (Parents) | Widowed | 50 (61.0) | 32 (39.0) | 1.34 (0.79, 2.25) | 1.06 (0.5, 2.24) |

| Divorce | 59 (53.2) | 52 (46.8) | 0.97 (0.61, 1.54) | 0.56 (0.27, 99) | |

| Lived gather | 114 (53.8) | 98 (46.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Orphan status | Single-orphan | 38 (51.4) | 36 (48.6) | 0.87 (0.524, 1.44) | 0.62 (0.32, 1.20) |

| Double-orphan | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 2.30 (0.81, 6.56) | 2.0 (0.52, 8.03) | |

| Non-orphan | 171 (54.8) | 141 (45.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| The child came from a household headed by | Child | 31 (47.7) | 34 (52.3) | 0.67 (0.38, 1.17) | 1.21 (0.54, 2.70) |

| Mother | 52 (55.9) | 41 (44.1) | 0.94 (0.57, 1.52) | 1.10 (0.54, 2.21) | |

| Father | 134 (57.5) | 99 (42.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Time stay (street) | ≥5 year | 28 (58.3) | 20 (41.7) | 1.61 (0.77, 3.35) | 1.15 (0.40, 3.32) |

| 3-4 year | 51 (58.6) | 36 (41.4) | 1.63 (0.86, 3.04) | 1.19 (0.50, 2.87) | |

| 1-2 year | 110 (55.8) | 87 (44.2) | 1.45 (0.84, 2.48) | 1.33 (0.60, 2.92) | |

| < 1 year | 34 (46.6) | 39 (53.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Food source | Begging | 42 (47.7) | 46 (52.3) | 1.52 (0.50, 4.54) | 0.64 (0.14, 2.82) |

| Buying | 68 (58.6) | 48 (41.4) | 2.36 (0.80, 6.93) | 1.19 (0.29, 4.87) | |

| Leftover food | 107 (57.8) | 78 (42.2) | 2.28 (0.79, 6.55) | 0.83 (0.19, 3.50) | |

| Home | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

Overall, about 223 (55.1%, 95% CI; (51, 61%) adolescent street children were psychosocially distressed. Being in the age range of 16-18 years old, meal availability once per day, being from a lowincome family, being sexually abused, meal availability twice per day, and being physically abused were significantly associated factors with psychosocial distress.

The magnitude of psychosocial distress in this study (55.1%) was in line with the findings in Iraq (61%) [33] and Ethiopia (51%) [21].

The possible reason for the similarity could be due to similarity in study designs, techniques, and the use of standard and reliable data measurement tools among studies. But it is lower than findings from India (92%) [17], Gahanna (87%) [11], Zambia (74%) [34] and Rwanda (63%) [35]. The difference might be due to the sociocultural, environmental, economic, and the difference in study subjects. The difference might be also due to the definition (GHQ- 12 cut point) and the variation in the duration of the studies [25,36]. The finding of this study is higher than from the global finding (10-20%) (8), Nepal (40%) (37) and Ethiopian (21.58%) [37,38]. The possible reason for the discrepancy might be due to the variation in the length of the time stayed on the street by the study subjects, study period, degree of exposure to the stressor, and social support to the street children provided.

This study assessed significantly associated factors with psychosocial distress. Being in the age group of 16-19 years old was 4.8 times more likely to have psychosocial distress compared to the age group of 10-12 years old. This is consistent with a study conducted in Mumbai, India [17], and Rwanda [35]. The reason might be due to that older children are minor mature and matured and communicating with others and expressing their feelings and thoughts they have and thinking about their future much than the others this might increase. Discussants also revealed as age increase they think more about their future life.

“Many thoughts repeatedly make me worry about my age. I am old age enough. My age is going on. I need to have a child and lead a family for the future but this is very difficult for me. I have no time to learn and the future hope of each street child is dark” (18 years old boy, FGD 3).

Those who availed meal once per day were 5.98 times higher odds of developing psychosocial distress compared to those who had availed meal three times or more per day. Those who availed meals twice per day were 3.68 times more likely to psychosocially distress than those who get three times and above per day. This was supported by a study in Rwanda [34]. The possible reason could be it is known that a human being to live needs basic necessities among the three is food. So if they did not get this basic necessity and they are always dependent they might think more about their day-to-day activity and this might increases psychosocial distress. Discussants also explained the consumption of their daily food was the day-to-day source of worry for the street children.

“We all, street children are suffered from and lacking all basic needs particularly what to eat and where to sleep at night: We are lucky if we get one or two meals per day. No one can give us money or bread unless we work. We spend our daytime looking for food usually “Auffa or Sukki” (leftover food) from hotels and restaurants or to find small jobs to earn money. We can do whatever we can to survive (A 16 and 18 years old boys, FGD2).

Street children whose parents have low income were 2.46 times more likely to have psychosocial distress compared to those whose parents have a good income. This is consistent with the study conducted in developing and developed countries [39]. The reason might be due to the decrease in income is difficult to fulfill even the basic necessities and also they may think about how to live which could increase psychosocial distress in children. Discussants explained that being from poor parents is among the main reason for street life and it increases psychosocial distress.

“……I have been in the street for the last 2 years. I am often visible around Mekelle Romanat and Hawzen Adebabay (squares in Mekele city). I am working on the street to help my mother because I have no other alternative to get money. I have no father. My mother is poor and could not raise her 3 children alone….” (17 years old boy, FGD1).

Bing physical abused was 2.43 times more likely to have psychosocial distress compared to non-abused street adolescents. This is consistent with the study in Nekemit [28]. The possible reason could be due to street children's lack of guardians, insecure on the street and hence they are vulnerable to cold and hot weather and also the environment where they are living is not safe for their life.

"It is very difficult to express this life for me, anybody who is around here will call us it is called "lekefa" when we go to them to communicate they touch our body and hugs us forcefully, and kiss me without my interest. If we refuse to come when they call us they hit us….so when they called us we do not have any option to refuse even we are not interested." (15 years old female, FGD4)

“…..Life on the street was very hard. Many times I used to get beaten by police for no reason. Sometimes also older street boys beat us for no reason and snatch our clothes and money that we got. They also frighten us without any reason and steal what we have and generally, for me living in the street is miserable and with no hope…..” (18 years old boy, FGD2).

In this study sexually abused street children were 3.61 times higher to have psychosocial distress than those who were not abused. This is supported by the studies conducted in Gondar [15]. The possible reason could be due to street children are highly involved in risky sexual behaviors to survive, older boys and watchmen of shops at night used new arrival street children as sex objects and the environment does not protect against such vulnerability.

“We street children have no one to stand for us. As far as you are in the street, you cannot escape except, accepting whether forced homosexual or heterosexual and even sexual misuse. You don’t have anyone to protect you, for whom would you cry (14 years old boy, FGD1, and 16 years old female, FGD 2).

“We usually sleep together boys and girls at the same house. We female street children are always on worry not to have sexual abuse and not to be pregnant. All boys on the street including our members try to talk to female street children about having sex voluntarily or forcefully, they kiss us and touching our breast without consent and even forced us to have sex. For example, I have raped by street adults sleeping with me and my friends. So that does not believe any boy knows (17 victim female street children, FGD4).

Street children are mobile and floating population. Therefore, it is difficult to maintain contact with the population. It is also difficult to draw the representative sample from such population.

More than half of street adolescents were psychosocially distressed. Age group 16-19, meal availability once and twice per day, being from parents with low-income status, being physical, and being sexually abused were significantly associated factors with psychosocial distress. Establishing and implementing local mental health policies and programs incorporating the needs and necessities of street children through collaborative efforts from various stakeholders, including the government and non-government sector to bring them into the mainstream of the society. Family-reintegration is also important to be encouraged to solve the problems of the street children and strengthen the legal systems to minimize the risk of physical and sexual abuses in the street children are crucial to decrease the problem.

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Financial issues for this work were covered by Mekelle University.

SM was involved in the inception and design of the study, conducted data collection and entry, performed analysis, and interpretation of data. GA assisted the analysis and interpretation of data, wrote the report, prepared the manuscript, and revised the paper. TA and HG were advised from proposal development up to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We would like to appreciate to Mekele University. Our heartfelt thanks also extend to supervisors, data collectors, and the study participants for their willingness and cooperation in the data collection process.

Citation: Mekonen S, Adhena G, Araya T, Hiwot HG (2020) Psychosocial Distress among adolescent Street Children in Tigray, Ethiopia: A Community-Based, Mixed-Method Study. J Depress Anxiety. 9:376. doi: 10.35248/2167-1044.20.9.376.

Received: 04-Oct-2020 Accepted: 06-Nov-2020 Published: 13-Nov-2020

Copyright: © 2020 Mekonen S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : Financial issues for this work were covered by Mekelle University.