Emergency Medicine: Open Access

Open Access

ISSN: 2165-7548

ISSN: 2165-7548

Research Article - (2015) Volume 5, Issue 4

Snake bite is a common life-threatening condition in many tropical countries. The highest burden of snakebites is in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Among these, India has the highest incidence of mortality from snakebite annually. Children are more prone for severe envenomation and complication due to lesser body surface area. This study was aimed at analyzing predictors of severity and factors involved in adverse outcome in pediatric snake envenomation. A descriptive evaluation for outcome determinants of snake envenomation was carried out based on a clinico – laboratory severity grading scale, among 60 out of 71 patients with envenomation in a tertiary care hospital in northern India from January 2008 to December 2013. Analysis was done using SPSS 17 trial version. Student t-test (unpaired), chi square tests, analysis of variance, coefficient of correlation and logistic regression were used to find out the predictors. Predictors associated with adverse outcome were neurotoxic envenomation, absence of local envenomation and cardiovascular involvement (OR 76.66, 95% CI (6.65-883.23), p value 0.001). Leucocytosis (pvalue<0.07), thrombocytopenia (p value<0.05), prolonged 20 minute clotting time (p value 0.008) were associated with severe envenomation and hence more complications. There was a relationship between grade of envenomation and the length of hospitalization (p=0.04), a shorter duration of hospital stay being associated with poor outcome (OR 0.425, 95% CI (0.212- 0.851), p value 0.02). So in order to reduce the mortality from snake bite, it is important for the patient to reach the hospital as early as possible so as to get timely and appropriate treatment with anti-snake venom to prevent the development or progression of complications.

Keywords: Envenomation; Nothern India; Outcome; Pediatric; Predictors

Snake bite is a common life-threatening condition in many tropical countries. The highest burden of snakebites is in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Among these, India has the highest incidence of mortality from snakebite annually [1,2]. Every year, 50,000 Indians die in 2,50,000 incidents of snake bite, despite the fact that India is not home for the largest number of venomous snakes in the world, nor is there a shortage of anti-snake venom in the country [3]. Mortality after snakebite is preventable if the victim receives timely treatment. Delay in seeking medical aid and ignorance among primary care physicians about the correct treatment of snake-bite is also responsible for the high morbidity and mortality [3,4]. There is an urgent need to spread awareness among the community for avoidance of traditional treatment and any delay in medical intervention in snakebite incidents. Snake bite was included in the list of neglected tropical diseases by World Health Organization in the year 2009 [2-5]. A National Snakebite Treatment Protocol has been developed, approved by Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India (Aug. 2007) for uniform implementation throughout the country. The aim of this study was to evaluate the major factors that influenced the morbidity and mortality of snake bite victims in pediatric population admitted in a tertiary care hospital in northern India where neurotoxic type of envenomation is predominant.

The study is a descriptive case series. A 6 year retrospective data was collected in the department of Pediatrics at Dr RPGMC Tanda, Kangra in Himachal Pradesh after ethical committee approval.

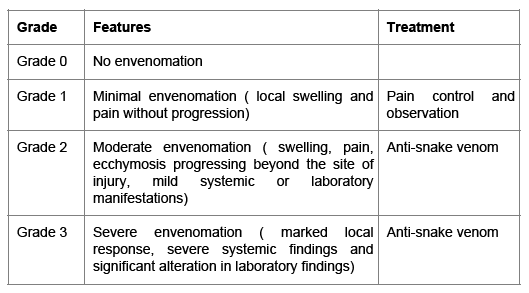

Seventy one children aged up to 16 years were found to have snake bite from January 2008 to December 2013. Sixty children with envenomation were enrolled. Eleven were excluded as had no symptoms and signs of envenomation. The clinic-laboratory severity grading scale used in study is shown in Table 1. The study aimed to assess laboratory profile, causes of complications and factors affecting the health outcomes.

Table 1: Classification of envenomation severity taken for grading the patient in present study.

Classification of envenomation severity taken for grading the patient in present study are given in Table 1. Four-point scale [6].

Neurotoxic Bites: Neuro-paralytic syndrome: Sensory or motor paralysis in the form of paresthesias, taste and smell abnormalities, ptosis, cranial nerve palsy, general flaccidity, or respiratory paralysis [6].

Hemotoxic Bites: Hemotoxicity: Bleeding from mucocutaneous sites, systemic bleeding, intravascular hemolysis, or deranged coagulation profile [6].

Neurovasculotoxic Bites: Features of both neurotoxicity and hemotoxicity as are seen as in russal viper envenomation [6].

Bite to needle time: It is the time elapsed before administration of antisnake venom.

Early morning bites: Bites occurring after 12 am and before 6 a.m [7].

20 Minute whole blood clotting time (WBCT): A few mililitres of fresh venous blood is placed in a new, clean and dry glass vessel. The glass vessel should be left undisturbed for 20 minutes and then gently tilted, not shaken. If the blood is still liquid then the patient has coagulopathy [8].

Analysis was done using SPSS 17 trial version. Student’s t-test (unpaired) was applied to compare the outcome and various dichotomous classifications for the measurable data. Chi-square was applied to compare the outcome and for the categorical/classified data. Analysis of variance was applied to compare the mean hospital stay as per severity (Local, moderate and severe). Coefficient of correlation was calculated for antisnake venom vials, bite to needle time, duration of ventilation, time taken for normalization of 20 minute clotting time and development of complications. Logistic regression was applied to find predictors of outcome (Survived/Died).

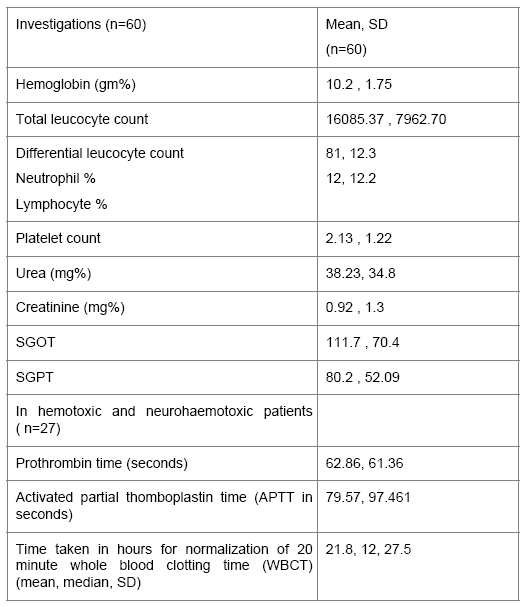

Leucocytosis with neutrophillic response was observed in severe envenomation. Abnormal 20 minute whole blood clotting time (WBCT) was seen in 27 (45.0%) patients. Median time taken for normalization of 20 minute clotting time was 12 ± 27.5 hours (6-144 h). Detailed laboratory profile of these patients is as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Laboratory profile of the 60 children with envenomation.

Subgroup analysis in mild (n=1), moderate (n=13) and severe envenomation (n=46) showed a total leucocyte count of 4900, 13317 and 16093 mm3 respectively. The mean platelet count was 2.1 lakhs however mean platelet count in children with haemotoxic and neurovasculotoxic bites having bleeds (n=17) was 59,400. Urea and creatinine were within normal range for other groups (Table 1) except in patients having acute renal failure (n=4) where urea and creatinine were 164 and 5.2 respectively.

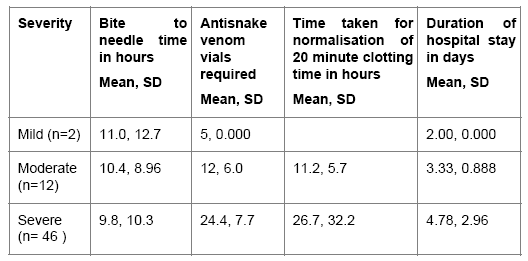

Longer the bite to needle, more severe is the envenomation. The patients who presented with severe envenomation required larger number of antisnake venom vials (ASV) to improve and took longer time for improvement and hence longer were the duration of hospital stay (Table 3).

Table 3: Relationship between bite to needle time, dose of antisnake venom, time taken for normalization of 20 minute clotting time and duration of hospital stay with severity of envenomation.

Delay in administration of ASV for more than 6 hours following envenomation was associated with a significant risk for the development of complications in both neurotoxic and hemotoxic envenomation.

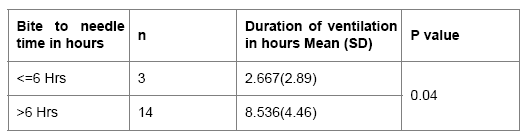

Among 60, neurotoxic, haemotoxic, neurovasculotoxic envenomation was seen in 32, 21 and 7 children respectively. Total 25 children had respiratory failure and required mechanical ventilation. Twenty among 32 cases with neurotoxic envenomation, 4/7 in neurovasculotoxic group while 1/21 required assisted ventilation in haemotoxic group. Out of these 25 patients, 8 died while 17 recovered completely without any sequelae. In survival group (n=17), children who received ASV 6 hours after the bite, required ventilation for longer duration (p value 0.04) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Relationship between bite to needle time and duration of ventilation in survival group ( n=17).

Among children with hemotoxic (n=21) and neurovasculotoxic bites (n=7) who presented with complications like acute renal failure (n=4) (p=0.01), hematuria (n=17) (p =0.01), haemoglobinuria (n=5) (p=0.04), spontaneous bleeds (n=7) (p=0.01) and intravascular hemolysis (n=6) (p=0.04) had thrombocytopenia along with deranged coagulogram.

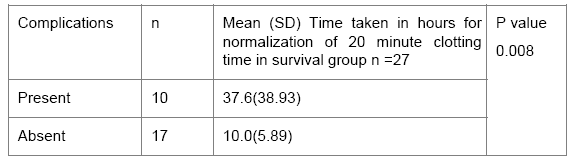

Patients who had prolonged 20 minute whole blood clotting time (WBCT) (n= 27) had severe envenomation. One patient in this group had mild envenomation with local symptoms and normal 20 minute WBCT. Children who took longer time for normalization of 20 minute clotting time after administration of antisnake venom as shown in Table 5 developed more complications like acute renal failure (p=0.004), hematuria (p=0.013), spontaneous bleeds (p=0.022), haemoglobinuria (p= 0.07), intravascular hemolysis (p=0.07).

Table 5: Relationship between time taken for normalization of 20 minute clotting time and development of complications in hemotoxic and neurohaemotoxic group ( n=27).

Different factors which were found to have association with development of complications were time of bite (p=0.03), time taken for normalization of 20 minute clotting time (p=0.01), number of ASV vials required (p=0.000), duration of hospital stay (p=0.04)

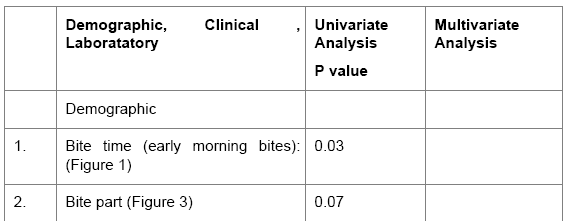

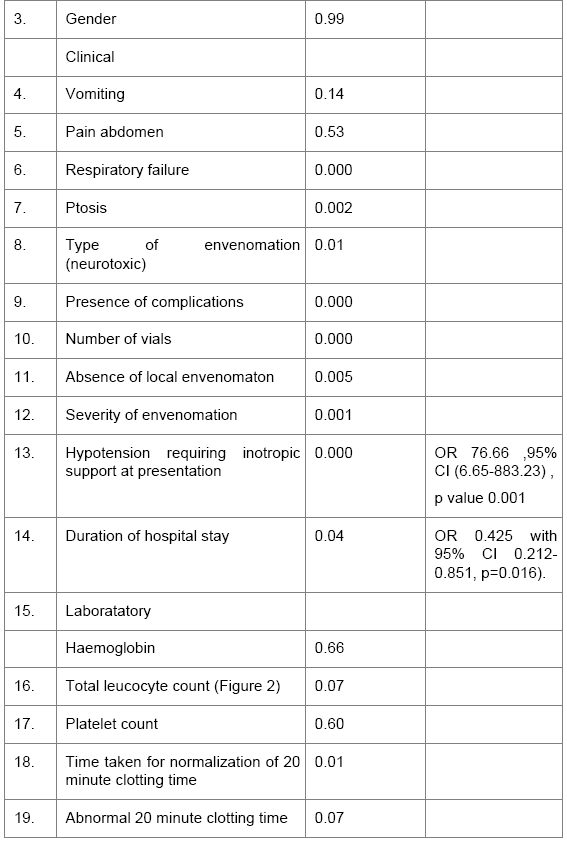

Factors related to outcome which were found to be statistically significant were presence of respiratory failure (p=0.000), ptosis (p=0.002), neurotoxic type of envenomation (p=0.01), absence of local envenomation (p=0.005), severity of envenomation (p=0.001) and hypotension requiring inotropic support (p=0.000) as shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Factors associated with severity of implication in patients.

Mortality was higher when the bite part was not known but it was not statistically significant (chi square 8.59, p=0.07) (Figure 1).

All children who died had neurotoxic envenomation. Time elapsed before administering ASV was 10.5+10.3 hours in the survival group, while in the mortality group it was 6.3+6.1 hours (chi square 0.112, p=0.9). The rate of complications increased as bite to needle time increased (Figure 2). This suggests that neurotoxic envenomation itself is a predictor of poor outcome in children if early treatment is not provided (p=0.01).

By stepwise logistic regression, hypotension requiring inotropic support depicting cardiac involvement is a strong predictor of mortality (OR 76.66 with 95% CI 6.65-883.23, p= 0.001) (Table 6). Duration of hospital stay was directly related to the patient outcome (OR 0.425 with 95% CI 0.212- 0.851, p=0.016) (Table 6).

Snake bite is one of the medical emergencies where timely intervention can save all lives. Severe envenomation and its complications are seen more commonly in victims presenting late. There are meager studies on snake bite envenomation in children. Most of the studies are from South India. Our was observational follow up for evaluating the health outcomes of snake envenomation in north Indian children where neurotoxic envenomation is predominant. Children are more prone for severe envenomation and complication due to lesser body surface area [9]. To best of our knowledge ours is the first study in north Indian children evaluating the severity and factors affecting the outcome.

Laboratory parameters associated with severe envenomation were leucocytosis, prolonged 20 minute WBCT and thrombocytopenia in case of haemotoxic bites. Similar observations were made in studies done in adults [10-12]. The 20 minute whole blood clotting test is a simple, rapid and reliable test of coagulopathy in snakebite envenomation [4]. In our study, a significantly higher number of complications were observed in cases where the 20 minute WBCT was prolonged. Myo-Khin et al. [13] in his study noted that unclotted blood after 20 minutes was associated with higher mortality. Haemostatic disturbances and bleeding tendency is well recognized as an indicator of greater risk of mortality.

This test can also be used to monitor venom neutralization in those treated with ASV. Although monitoring of protrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) might give a better clue of the degree of consumption coagulopathy but the time taken for their normalisation may be long [14].

The incidence of complications is directly proportional to the duration for which the venom is present in the blood prior to its neutralization by ASV [15].

In our study, the correlation between development of complications and bite to needle time was observed to be similar to that seen in other studies [11-12,16-20], thus emphasizing timely administration of ASV. Patients who presented late had severe envenomation, required higher number of ASV vials and required more aggressive interventions like mechanical ventilator support. It is known that delayed infusion of more ASV may not be helpful once dreadful complications like renal failure and coagulopathy have developed. However reversal of coagulopathy and improvement of local signs of envenoming have been seen even after delayed administration of ASV [12]. Similarly there are also conflicting reports about the usefulness of ASV and its dosage in reversing some of the neurological complications and respiratory paralysis [20,21].

The presence of neurological signs and symptoms, abdominal pain and absence of local reaction favors a diagnosis of krait envenomation [14]. In our study, absence of local envenomation and the related symptoms might have been one of the reasons for late admission and hence the poorer outcome. Since krait bites are usually painless with mild local symptoms, the bite may at times, go unrecognized resulting in delayed treatment and consequently higher mortality [22].

The overall incidence (41%) of respiratory failure in our study was comparable to other reports [23,24]. Patients who received ASV after 6 hours of bite required longer duration of ventilation. Similar findings were seen in other studies [25].

Mortality in our study was 13.3%. In hospital based studies in children, mortality rates ranged from 3% in northern India [10] to 13% in southern India [26]. Mortality has been observed to be low in hemotoxic as compared to neurotoxic envenomation [27].

In our study, it was observed that outcome of snake bite depends upon multiple factors. On univariable analysis, the risk factors found to be significantly associated with adverse outcome were: ptosis, neurotoxic envenomation, presence of complications, absence of local envenomation, hypotension requiring inotropic support and duration of hospital stay. Gender, vomiting, pain abdomen and abnormal 20 minute clotting time were not significantly associated. Stepwise logistic regression showed that hypotension requiring inotropic support and a shorter duration of hospital stay were significantly associated with increased risk of mortality. The patients with a shorter duration of hospital stay had severe systemic envenomation and complications which allowed less time for adequate intervention. This resulted in a poorer response to treatment and consequently a higher mortality. Similar observation was made in another study [11].

Early morning unrecognized bites, neurotoxic envenomation, bite to needle time more than 6 hours, presence of ptosis, hypotension, bleeding tendency, leucocytosis and prolonged 20 minute whole blood clotting time were factors that influenced the severity and outcome of envenomed victims. So in order to reduce the mortality from snake bite, it is important for the patient to reach the hospital as early as possible so as to get timely and appropriate treatment with anti-snake venom to prevent the development or progression of complications.