Journal of Horticulture

Open Access

ISSN: 2376-0354

ISSN: 2376-0354

Research Article - (2025)Volume 12, Issue 1

Cassava is a widely produced root crop serving as food security in developing countries. There were number of efforts so far done on morphological, compositional and molecular variability-based study. However, little review and organized document of such works based on the whole marker information in one. So, this paper presents the results of these research. Through this review, variability of different genotypes across the world were recognized from different studies even though range of variability varied from report to report based on number of accessions and sources of studied materials used. Accordingly, morphological marker-based analysis classified studied genotypes into different groups where their first two to three PCA showed high percentage of variation. The biochemical markerbased analysis also showed significant differences. This genetic variability of the crop enables to grow and perform in wider agro-ecologies unlike other crops. Also, it has an opportunity of gaining heterosis under breeding and trait improvement through both conventional and modern breeding methods. The molecular marker-based diversity also revealed significant variation among assessed cassava genotypes. So, systematic germplasm collection and strategic conservation is recommended.

Cassava; Diversity study; Morphological markers; Biochemical markers; Molecular markers

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is a woody plant of 1-6 m height belonging to Euphorbiaceous family, genus Manihot and species of Manihot esculenta. The crop is diploid (2n=36) and also polyploids with 2n=54 and 72 are available. It was originated from north-east Brazil, along southern rim of the Amazon basin extending to Bolivia and later distributed by Portuguese to Africa, Indonesia, Singapore, Malasia and India. Cassavas typically grow as perennial shrub with palmate leaves bearing three to nine lobes having either spread or erect stem structure.

Cassava is the third largest food crops of the world and staple foods in fresh or in processed form in sub-Saharan Africa. Its leaves also serve as vegetable and its root as sources of industrial input.

Cassava due to its broad genetic bases can grow in wide altitudinal range and different soil types as well as marginal area and provide reasonable yield where other crop can’t grow. Even though it can tolerate drought, it performs well at an annual rainfall of 600-1500 mm and temperature of 25-29°C. It can grow throughout tropical regions of the world between latitude 300 N and 300 S with up to 2000 m altitude [1].

In the major cassava producing countries in Africa such as Nigeria, DRC, Ghana, Tanzania, Mozambique, Uganda and Madagarskar, it is widely produced by farmers. However, there were no well-defined and organized genetic conservation strategies in these countries. Additionally, cassava breeding is limited to certain extent because of its nature of flowering and poor germination; and limited knowledge of genetic diversity among closely related species. So, genetic markers have become fundamental tool for understanding inheritance and diversity of natural variation. Genetic diversity is fundamentally indispensible in crop improvement and provides plants with the capacity to meet the demand of changing environments. Genetic variability study of cassava germplasm is valuable tool for breeding, selecting outstanding materials with desirable traits such as yield and tolerant to different stress and for further conservation strategies.

In order to sustain genetic diversity through conservation preidentification of these available germplasm is crucial activities in saving resources and time. So that, numbers of researches were conducted so far by different scientists on diversity analysis of cassava germplasm and accession to confirm real difference of farmers’ landraces, accessions and elites using phenotypic, biochemical or molecular markers; however, DNA based molecular markers are reliable and robust methods for characterization of genetic diversity. Genetic markers of cassava have become fundamental tools for understanding the inheritance and diversity of natural variation. In cassava the earlier genetic marker was morphological which based on physical appearances of cassava. The agro-morphological traits are frequently used in the preliminary evaluation because they are fast and easy approach for assessing the extent of diversity. The second generation markers were biochemical like isozymes which provide useful tool for genetic fingerprinting. DNA markers have got the third generation becoming powerful tools for genetic diversity of germplasm analysis which includes Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP), Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR), Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD), Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP). So far little information on well documented review on all markers based cassava diversity study done worldwide. So, this paper is aimed to review different cassava diversity studies so far done.

Diversity assessment in cassava

Morpho-agronomic based diversity study: Morphological diversity study is one of the markers used to identify duplicate, diversity and correlation available within panel using phenotypic attributes of organisms. Numbers of experiments were conducted to verify distinction prevailing within and among cassava germplasm accessions at different level in different countries [2]. In Ghana, clarified the variability of 43 cassava accessions based on 19 morphological traits such as (young leaf color, leaf vein color, pubescence on young leaf, petiole length, stem length, root length, diameter, root surface color, root pulp color, root apex color, petiole color, plant height and yield) where their first PCA I, II and III accounted for 46.6%, 14.7%and 11.4% and stated that accessions were genetically diverse for the considered traits. As a result, dendrogram grouped 43 accessions into two main clusters with two sub-clusters each having different size/ numbers of accessions (cluster I (5), II (10), III (10) and IV) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Dendrogram showing morphological based diversity of 43 cassava accessions (extracted from).

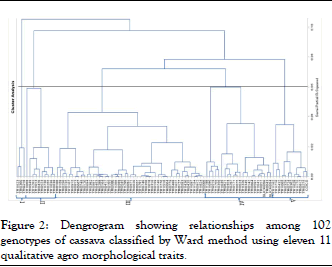

Similar results were reported by who were conducted cassava diversity analysis using 22 agro-morphological traits encompassing 11 quantitative and 11 qualitative attributes in Siera Leone. For their study, they used 102 cassava genotypes comprising 82 white and 20 yellow fleshed root accessions. The hierarchical classification of qualitative traits grouped genotypes into four classes in which each cluster accommodated different numbers of genotypes. Cluster I, II, III and IV each comprised 19, 12, 46 and 25 genotypes respectively (Figure 2).

The analysis of morphological traits (root taste, external storage root color, color of root pulp, ease of peeling, color of leaf vein, lobe margin, leaf color, color of apical leaves and shape of central leaflet) showed significant variation among studied genotypes. Accordingly, frequency distribution of 53.9% of accessions exhibited light green, 42.2% dark green and 3.9% purple green leaves were reported (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Dengrogram showing relationships among 102 genotypes of cassava classified by Ward method using eleven 11 qualitative agro morphological traits.

Concerning leaf vein about 67% green, 27% reddish green and 6% exhibited reddish green in less than half of lobe. Leaf lobe margin of 52% accession with smooth and 48% were wrinkled were reported in.

Quantitative and qualitative attributes of 183 cassava accessions were recorded and significant variation reported in which plant height ranged from 65.5 cm to 284.5 cm and yield ranged from 0.2 t/h to 42.5 t/h while dry matter content ranged from 4-44.5%.

Figure 3: Percentage distribution of different morphological traits.

In terms of external color of root characteristics, 5.9% of external color was white or creamy, 17.6% light brown and 76.5% dark brown (Figure 3). In agreement to this finding, genetic diversity study based on 11 quantitative traits i.e, yield and related attribute conducted on 35 cassava germplasm provided broad genetic base and the accessions clustered under five groups in which number of each cluster comprised of 1 to 15 genotypes [3]. The distance analysis between two clusters (Table 1) was reported highly significant indicating variability and probability of high heterotic response under mating.

| Cluster | Cluster I | Cluster II | Cluster III | Cluster IV | Cluster V |

| I | 0 | 2144.4** | 5004.38** | 7022.64** | 13809.60** |

| II | 0 | 2860.50** | 4884.73** | 11666.10** | |

| III | 0 | 2041.45** | 8807.90** | ||

| IV | 0 | 6828.0** | |||

| V | 0 | ||||

| Note: *=Significant at 0.05 probability level (X2 10=18.31) **=Highly significant at 0.01 probability level (X2 10=23.21) |

|||||

Table 1: Pair wise generalized squared distance between five clusters of cassava.

Biochemical and anti-nutritional composition based diversity study

Biochemical composition based variation of cassava: Cassava has multifarious in food, feed and industry and its nutritional quality and composition of tuber; stem and leaf of important 19 varieties have been systematically studied in India. The study showed that, large difference in biochemical, mineral and proximate composition reported. Accordingly, starch content in tubers among these studied 19 varieties showed variation range of 24 to 40.91% with larger variation while the total sugar ranged from 0.74 to 1.33%. The biochemical composition such as polyphenol, nitrogen and polyphenol/N ratio were reported ranging from 0.003 to 0.012%, 0.413 to 0.973% and 0.004 to 0.02 respectively. In leaf also, phenolic content ranged from 0.01 to 0.064% and N contents in dry weigh based ranged from 3.18 to 5.71% respectively. Similarly, mineral composition of these studied cassava varieties showed vast variation in P (0.03-0.08%), K (0.327-1.087%), Ca (1083-1858 ppm) and Mg (540-895 ppm).

Also, proximate contents like moisture, ash, crude protein, crude fiber and lipid of tuber varied from 56.67-70.19%; 2.0 -2.07%; 0.85-2.00%; 0.08-0.39% and 0.15-0.37% respectively were reported. Chisenga, et al. also published almost related result of protein content which ranged from 1.21-1.87%, crude lipid content range of 0.15-0.63%, ash 1.2-1.78% and crude fiber 0.03-0.60% varied from variety to varieties. However, the moisture content (10.43 to 11.76%) reported by these guys was very small as compared to the former report (56.67-70.19) which might be due to moisture deficiency of the area or over drying of the samples. On the other hand, the statement reported by evidenced that similar range of moisture content (50.48-90.43%), crude protein (0.01-1.45%); and fat (0.07-1.22%), crude fiber (0.47 to 2.57%); crude ash (1-2%) and carbohydrate content (6.85-45.79%) of 10 orange and white cassava germplasm were reported clarifying that protein content of root of orange fleshed is greater than that of white. This could be due to carotenoid content of orange colored roots. Similarly, they reported the Total Carotenoid Contents (TCC) vary from 1.18 to 18.81 g/kg in fresh weight based among two white and 8 yellow fleshed roots with higher TCC in yellow fleshed root. In all the above reports, the crude protein content variation of cassava accessions treated alike is due to varietal difference but the great variability report from different authors in different countries might be due to both varietal variation and response of plant to soil nitrogen contents which agreed with the statement of response of forage in crude protein was similar to function of the N doses i.e., nitrogen application promote a linear increase in N accumulation in the shoot [4].

Berhanu, et al. assessed biochemical compositions of 64 cassava genotypes in Ethiopia. The nutritional composition assessed were starch, crude protein, crude fat, crude fiber, organic matter, carbohydrate, energy, ash, dry matter and anti-nutritional content such as cyanide and tannin content. Accordingly, the concerned compositions showed variation from 4.83-10.11% for MC, 2.10-3.96% for ash, 0.26-1.40% for crude fat, 1.14-3% of fiber content, carbohydrate and protein range of 81.29-87.84%and 1.28-2.46% respectively. These compositional variations indicated the presence of variation in their genetic makeup providing opportunity in cross breeding with resultant of heterosis.

Anti-nutritional composition based variation of cassava germpasm

One major setback in utilization of cassava is hydrogen cyanogen potential of root, the fear of poisoning. Based on cyanogenic content, cassava grouped into two sweet and bitter. The content in root was reported to range from 1-1550 mg HCN/kg of fresh weight. Internationally, standard for sweet cassava is less than or equal to 50 mg/kg in weight basis and concentration between 50 to 80 mg/kg may be slightly poisonous; 80-100 mg/kg is toxic while concentrations above 100 mg/kg grated cassava are dangerously poisonous. In order to utilize cassava for consumption or for industrial purpose, the cyanide range should be determined. Chisenga et al. in Zambia assessed six varieties and reported HCN range of 23.60 to 238.12 ppm showing significant variation (p<0.05). So the varieties can be categorized as sweet and bitter or; slightly, moderately and highly poisonous. The cyanide content of three cassava cultivars was reported also 50.13 to 50.24 mg/kg which is in range of moderate/slightly poison and no more variation unlike the finding of that was evaluated large number of genotypes. Similarly, the HCN concentrations ranged in root of ten germplasm of cassava were reported from 25.77-39.63 mg/kg with no more differences. These genotypes categorized under sweet types of cassava genotypes which recommended for consumption.

Besides, hydrogen cyanide concentration contents of 46 cassava accessions were assessed to categorize them as sweet (for consumption) and bitter for other purpose industrial applications by. As a result, the cyanide content of accessions varied from 50 to 100 mg/kg and they stated that HCN can be influenced by environmental condition. They also evaluated two population of bitter and sweet cassava for carotenoid and protein content and found that larger carotenoid (10.88-18.41 mg/kg) and protein 0.46-2.27 in bitter cassava while in sweet cassava carotene ranged from 2.08-4.38 gm/kg and protein 0.18-1.10% respective. Similarly, their achievement revealed that starch and sugar content of bitter types were higher than the sweet group. This result is in agreement with finding in another study with cassava accessions sampled in Brazil. So, bitter cassava provides opportunity as parents in improvement breeding of the sweet type. Also, since leaf of cassava cooked and consumed as vegetable anti-nutritional composition like cyanide and tannin in leaf of six varieties were evaluated and significant variation of these concerned traits were reported which ranged from 11.29-19.29 mg/kg which exceed recommended cyanide level in food 10 mg/kg in dry weight based. These genotypes having HCN range beyond the recommended for consumptions are categorized under bitter types and serves for industrial implications [5].

Molecular diversity study

Genetic variation among genotypes is important for sustainable use of genetic resources to meet the demand for food security, breeding purpose and conservation strategies. Morphological variability study may not show real difference of the genotypes due to environmental and genotype by environment interaction effects. To confirm real diversity, molecular marker based work done so far were reviewed.

SSR and SNP marker based diversity study

Turyagyenda, et al. conducted genetic diversity study of fifty-four cassava accessions (39 landraces and 15 elite accessions) using 26 SSR markers. The result of their study revealed all markers were polymorphic for both populations. A total of 154 polymorphic alleles ranging from 2 (SSRY147) to 10 with (SSRY100 and SSRY69) per locus for landraces and 2 alleles (SSRY147 and SSRY5) and 8 alleles (SSRY64 and SSRY100) for elites were reported respectively. The mean expected heterozygosity (gene diversity (He)) across loci were reported by ranged from 0.477 in SSRY155 to 0.842 in SSRY64 with an average of 0.667 which means randomly selected individual from accessions/population are different by 66.7% also termed as genetic diversity, while observed heterozygosity ranged from 0.273 to 0.985 in SSRY59 and SSRY148, respectively, with an average of 0.726 indicating maximum outcrossing of 72.6% with PIC values of loci across the groups was highest in SSRY64 (0.822) and lowest in SSRY 155 (0.377) with average of 0.611. In similar manner, Raji, et al. who conducted experiment on cassava collection from different countries in Africa reported average He and Ho values of 0.63 and .073 respectively.

Asare, et al. also conducted molecular based diversity study of 43 cassava accessions using 36 highly polymorphic SSR markers. The authors indicated 20 out of 36 primers resulted polymorphic with 100 total numbers of alleles detected for the 20 primers among the 43 cassava accessions subjected to analysis whereas the rest showed monomorphic failed to amplify any product. The numbers of alleles per locus ranged from 2 in SSRY181 to 9 in SSRY20 and SSRY175). The Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) value of the 43 accessions ranged from 0.07 in SSRY181 to 0.75 in SSRY175 where gene diversity was high ranging from 0.07 in SSRY181 to 0.78 in SSRY175 with average value of 0.58. Also, they reported observed Hetrozygosity (Ho) from 0.07 for SSRY181 to 1. These genotypes clustered under two main groups with 9 different sub-clusters where these clusters varied comprised of 1 to 16 accessions (Figure 4). In agreement with under study conducted on 300 cassava landraces and 3 commercial cultivars collected in different parts of Brazil by total of 95 alleles were identified using 15 microsatellites. They found that number of alleles per locus ranged from 4 to 10 with mean of 6.33 and allelic frequency of 0.242 (SSRY21) to 0.789 GA 136) with mean of 0.453. Also observed heterozygosity of 0.6511 and expected heterozygosity at loci of SSRY21, SSRY 45 and GA 131 were reported to be 0.8116, 0.7827 and 0.7774 respectively with highly informative PIC value were 0.6057 [6].

Figure 4: Dendrogram showing genetic dissimilarity among the cassava accessions based on SSR data.

In similar manner, leaves samples of two populations, 23 cassava germplasm accessions with known and 162 cassava genotypes of unknown with total of 185 genotypes were collected from different Island of Puerto Rico for molecular based diversity study. The authors utilized 36 SSR markers out of which 33 markers detected 293 alleles which varied from 2 to 14 per locus with average 7.15+1.03 alleles per/locus. Generally, all loci were reported to be polymorphic in all countries and high HE (0.7357+0.1193) and HO (0.6705+0.0226) across all loci and all accessions were reported in this review. Similar experiment was conducted by on cassava accessions collected from Tanzania (270 genotypes); Uganda (268); Kenya (234); Rwanda (184); DRC (177); Madagascar (186); Mozambique (82) with total of 1401 accessions genotyped for 26 SSR loci and total of 192 alleles with average of 7.38 alleles per locus were reported [7].

Genetic distance of some samples revealed relative similarity which might be exchange of materials between local farmers (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Principal coordinate analysis of SSR amplified pattern of the two populations assessed cassava accessions showing level of relatedness and diversity.

The average within population heterozygosity was reported 0.708 with inbreeding coefficient do not close to zero implying neither inbreeding nor outbreeding was occurred which implied occurrence of genetic drift. Rare alleles with frequency of 0.003 and 006 for SSR181 and SSR161 were reported.

Danquah, et al., conducted research to assess genetic diversity of 89 cassava genotype accessions from IITA (40), CIAT (12) and local (37) using 36 Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) primers commonly distributed along cassava genome. By means of this method, total of 167 alleles were generated with averahe allele frequency of 0.62 maximum frequencies 0.99 for SSR-164. In parity with the achievements of reported closer PIC values ranged from 0.03 to 0.78 with mean of 0.45 where the peak PIC for SSRY-164 primer. For each population IITA, CIAT and local, 0.47, 0.40 and 0.49 and cluster analysis based on neighbor joining method grouped into 7 clusters (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Relation between 89 cassava accessions from Local (Blue), IITA (Red) and CIAT (Green) based on neighbourjoining analysis.

Out of total of 195 SNPs markers used for Genotype by Sequencing (GBS) of 105 cassava genotypes collected from different agro-ecologies of cassava growing areas of Ghana, 96% were polymorphic and 4% (8) were monomorphic which was in agreement with the finding of reported 1.5% of monomorphic SNPs markers of analyzed 1280 cassava accessions with 402 SNP markers. They reported PIC value varied from 0.049 to 0.375 with average of 0.286. PIC measures the informativeness of a marker where the higher the PIC, the more informative. However, PIC value is low not more than 0.5 in SNP than in SSR due to its bi-allelic nature and SSR is multi-allelic value can go up to 1, even though SNP is more informative [8].

Variability study of 134 cassava accessions from different 11 countries were done by using 107 pairs of EST-SSR (which is short DNA sequence from which PCR primers derived sequence) markers men MAF per locus reported 0.62 which ranged from 0.29 to 0.99; gene diversity (He) ranged 0.02-0.4; the number of alleles per locus was ranged 2 to 8 with average of 2.8 and the polymorphic information content value ranged also from 0.02 to 0.77 with average 0.41. Using 163 cassava genotypes collected from different sources i.e., IITA, CIAT and Cuba breeding program were evaluated using 36 SSR primers and 34 of the primers were polymorphic with 2-10 alleles per locus with average of 4.64 and the average expected heterozygousity reported was high 0.6292 ± 0.0120 whereas Ho was also high (0.5918 ± 0.0351) which verify the outcrossing and highly heterozygous behavior of cassava. Similar finding was reported by where a total 120 cassava landraces cultivated in Brazil were studied for heterozygousity with 14 microsatelite markers and total of 97 alleles were amplified at an average of 7/ locus with genetic diversity estimated by expected (0.674) and observed (0.875) heterozygosity were very high; the Polymorphic Information Content (PIC) which estimate the quality of molecular markers to detection of polymorphism among individual (classified as satisfactory (PIC>0.5), medium (0.25 ≤ P ≤ 0.5) and low (PIC<0.25)) i.e., in this study was ranged from 0.292 (SSRY126) to 0.821 (SSRY27), with average of 0.621.

Genetic variability study using SNP was conducted. Cluster analysis based on 5600 filtered of missing value informative SNP markers were grouped 96 cassava genotypes into three clusters; where each clusters has sub clusters at different similarity. At similarity of 0.41, three main clusters were reported. Also, at similarity of 0.37, both Cluster-I and II each encompassed two sub groups A, B, C D with 2, 18, 6 and 22 accession respectively. Cluster III has four sub-clusters each comprising 5, 33, 3 and 6 accessions in that order. The authors stressed that molecular study showed 96% of the 5600 SNP markers extracted polymorphism with highest Polymorphic Content of (PIC) value of 0.17. In parity with this finding, high PIC of value of 0.228 in 74 cassava accessions was reported.

The same authors in another experiment conducted molecular marker based diversity study on 1443 cassava genotypes collected from different cassava breeding programs of countries of east Africa Tanzania (270 genotypes); Uganda (268); Kenya (234); Rwanda (184); DRC (177); Madagascar (186); Mozambique (82) using 26 SSR markers. Consequently, they reported 42 of genotypes showed monomorphic whereas 1401 genotypes revealed high polymorphic amplification total of 192 alleles with 7.38 alleles per locus. They reported gene diversity of 0.633 with high observed mean heterozygosity of 0.57 due to outbreeding nature of cassava (Figure 7) [9].

Figure 7: Dendrogram generated by UPGMA method of 96 cassava accessions based on SNP markers.

Cassava is the widely produced root crop serving as food security in developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa. The different morphological, compositional and molecular variability based studies carried out so far reviewed indicated vast variation between studied genotypes. This genetic variability of the crop enables to grow and perform in wider agro-ecologies unlike other crops. But, due to limited research oriented toward development of cassava in majority of cassava growing countries and low attention provided to this crop, there will be probability of genetic loss occur. However, the achievement reviewed gives insight enabling systematic germplasm collection and strategic conservation as well as cross breeding for nutritional constituent improvement and other traits of interest.

I want to express the great appreciation I have for all authors of the reviewed articles for their valuable works.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

No funding received.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Abadura NS (2025) Genetic Diversity in Cassava (Manihot Esculenta (Cranz)) and its Implication in its Improvement. J Hortic. 12:377.

Received: 07-Aug-2024, Manuscript No. horticulture-24-33424; Editor assigned: 12-Aug-2024, Pre QC No. horticulture-24-33424 (PQ); Reviewed: 26-Aug-2024, QC No. horticulture-24-33424; Revised: 23-Jan-2025, Manuscript No. horticulture-24-33424 (R); Published: 30-Jan-2025 , DOI: 10.35248/2376-0354.25.12.377

Copyright: © 2025 Abadura NS. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.