Journal of Cancer Research and Immuno-Oncology

Open Access

ISSN: 2684-1266

ISSN: 2684-1266

Review Article - (2020)Volume 6, Issue 1

Background: Triage in an emergency department (ED) plays a pivotal role as the volume of ED visitors is

unpredictable. All ED patients are triaged to make sure that patients with urgent or life-threatening conditions are

seen immediately while others with more stable conditions are safe to wait.

Purpose: To examine the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) guidelines to determine if the urgency of

oncological emergencies can be prioritized appropriately using the CTAS guidelines.

Methods: We used the Complaint Oriented Triage (COT 2012), which is an interactive computerized CTAS tool, to

triage select oncological emergencies; superior vena cava syndrome, cardiac tamponade, tumor lysis syndrome, and

febrile neutropenia.

Results: Patients with cancer have a higher acuity compared to many other ED patients. However, most of the

oncological emergencies can be subtle and nonspecific. The CTAS guidelines need to be strengthened to better

represent the urgency of these life-threatening conditions.

Conclusion: Although revisions have been implemented and the reliability of the CTAS tool has improved, the

guidelines are designed to be generic and cannot address every health situation. Febrile neutropenia is an excellent

example of the additional supports needed at triage to accurately determine the patient’s health status. Knowledge of

the signs and symptoms of these emergencies will enable triage nurses to accurately differentiate the urgency of the

different presenting complaints. Formalized education that prepares triage nurses to better understand the complexity

of the symptom presentation and the needed care for patients with different oncological emergencies is essential.

Febrile neutropenia; CTAS; ED; Quality of care; Timeliness of ED care; The Canadian triage and acuity Scale; Emergency triage; Oncological emergencies

Cancer is a serious public health problem that remains a significant cause of mortality worldwide [1]. In Canada, cancer is the leading cause of death and is responsible for 30% of all deaths. Prevalence of cancer is also on the rise with improved survival due to advances in treatment and targeted therapy [2,3]. However, treatment continues to be aggressive causing severe complications and contributing to the prevalence of cancerrelated emergencies [4,5].

The emergency department (ED) is considered an important entry point into health care for individuals with cancer requiring urgent treatment [6]. In the ED, patients are sorted by priority in a triage process, which plays a pivotal role as the volume of ED visitors is unpredictable. All ED patients are triaged to make sure that patients with urgent or life-threatening conditions are seen immediately while others with more stable conditions are safe to wait [7]. However, the assessment and identification of seriously ill oncology patients is problematic as patients can present with non-specific symptoms, which could lead to extensive delay in ED treatment and negative health consequences [8]. Findings from available studies revealed that most cancer patients suffer significant delays seeking emergency care even when they present with oncological emergencies [6,9].

The recognition of oncological emergencies is essential to establish the correct identification and prompt delivery of appropriate care [5]. It is the responsibility of the triage nurses to identify those patients correctly to ensure prompt assessment and treatment in the ED. In this paper, we have three main objectives. We first review selects oncological emergencies that are regularly treated in the ED and discuss the characteristics and outcomes of each. Febrile neutropenia (FN) is given a particular focus because it is the most common oncological emergency. Second, we conduct a critical evaluation of the effectiveness of the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) in identifying the urgency of common oncological emergencies. Finally, we provide some recommendations for refining the CTAS guidelines and evidence-based strategies which, if implemented, would improve the ED care of oncological emergencies.

We used the Complaint Oriented Triage (COT 2012) - (English Canada Version 02.02) to triage select oncological emergencies. The COT is an interactive computerized tool used in Canadian EDs to triage patients. This tool is based on the 2012 version of the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS 2012), Pediatric CTAS (Ped-CTAS 2012), and the Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS 2012) Chief Complaint list v2.0. It was established by the CTAS National Working Group and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, by integrating the national CEDIS presenting complaint list with the CTAS modifiers. The COT Power point application can be freely downloaded from the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians website. The authors evaluated the process of ED triage using the common manifestations of each oncological emergency. The purpose was to examine if these emergencies can be prioritized appropriately using the CTAS guidelines.

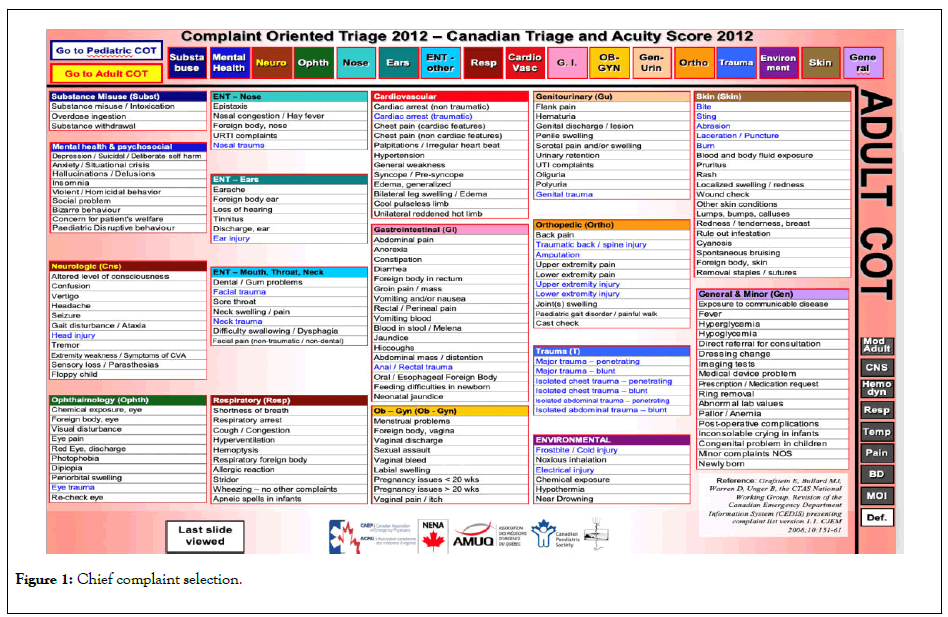

This COT tool is intuitive and can guide the triage decision through the triage assessment until the appropriate triage score is assigned to the patient. Triage assessment using this tool starts with age selection as the nurse can select between adult CTAS (CTAS 2012) or pediatric CTAS (Ped-CTAS 2012). In the 2nd step, the nurse selects the chief complaint as described by the patient (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chief complaint selection.

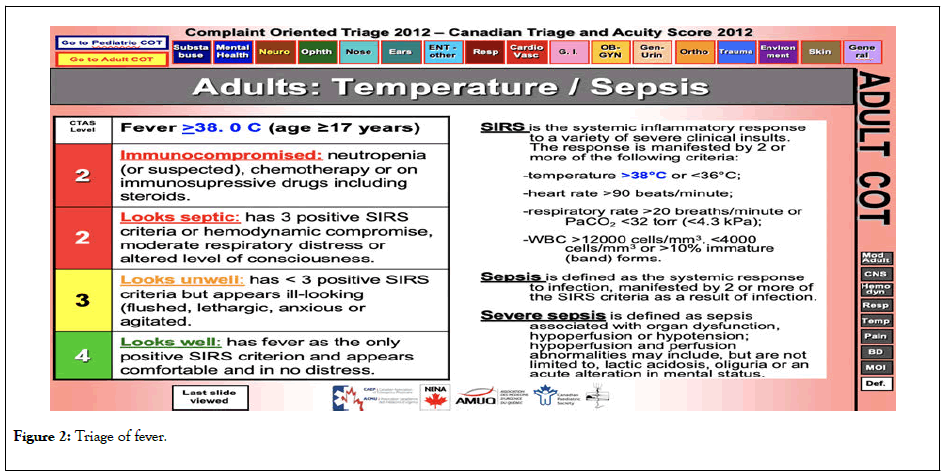

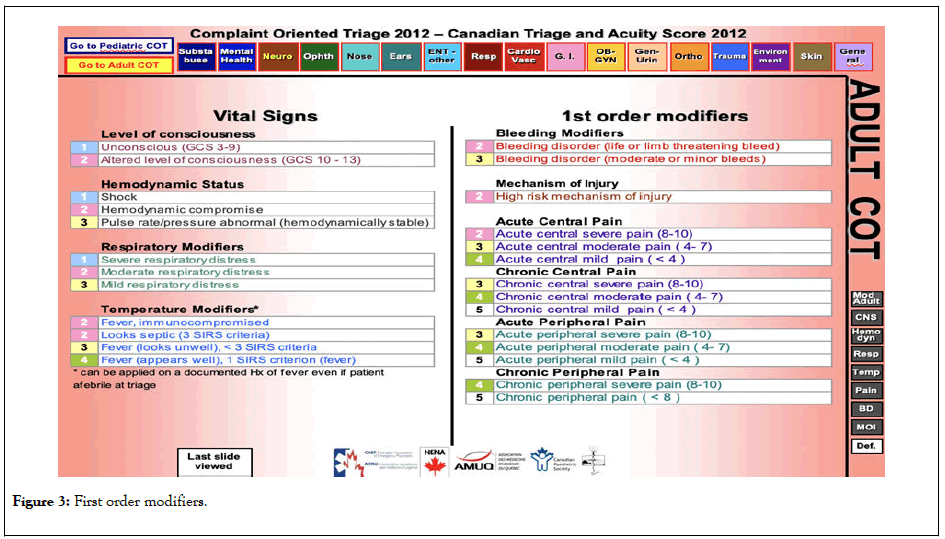

For the demonstration, a triage nurse considered a patient with cancer who presented with fever. If a nurse selects “Fever” from the “General and Minor” icon or the temperature icon from the sidebar, the tool will transfer the nurse to a different screen as seen in (Figures 2 and 3) respectively. From these screens, the nurse can see that patients who are immune-compromised with neutropenia (or suspected) are supposed to receive a triage score of 2 without the need for any further assessment. The guidelines define immune-compromised status as those with neutropenia (or suspected neutropenia) or on chemotherapy or immunosuppressive drugs including steroids [7].

Figure 2: Triage of fever.

Figure 3: First order modifiers.

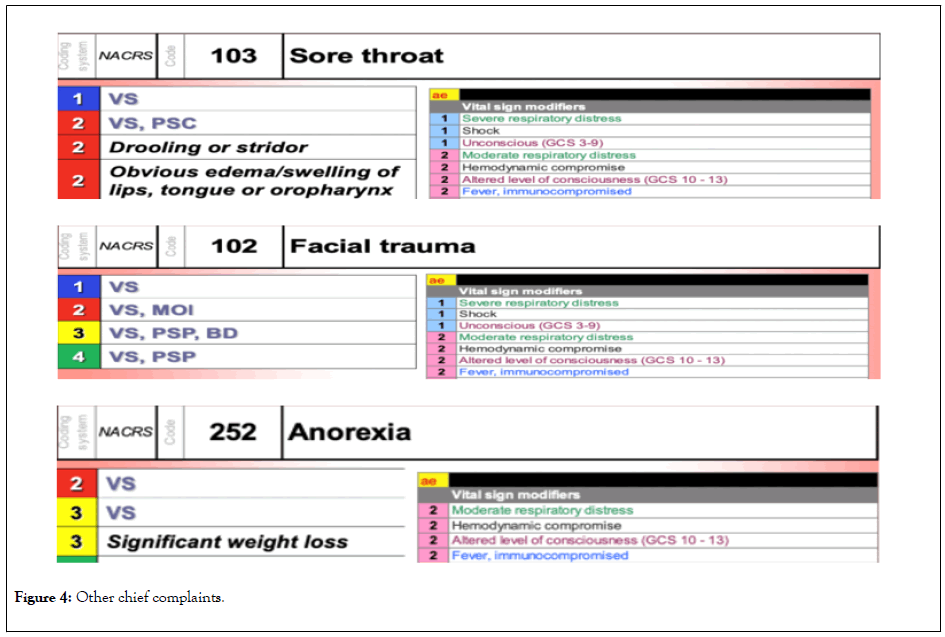

Furthermore, the COT system guides the triage nurse to assign a triage score of 2 to any immuno-compromised patient regardless of their chief complaint, if this patient has a temperature at the time of triage. Complaints such as chest pain, hypertension, general weakness, leg swelling, facial trauma, sore throat, facial pain, and even a complaint such as anorexia are considered as potentially indicative of sepsis (a complication of FN) if the patient has an increased temperature at triage (Figure 4). Similarly, we have applied the 2012 COT in the triage of remaining oncological complaints and emergencies. In this article, however, we only report on four of the most lifethreatening oncological emergencies including superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS), cardiac tamponade, tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), and febrile neutropenia (FN).

Figure 4: Other chief complaints.

The urgency of the oncological complaints

Although cancer is a chronic disease, patients with cancer can still experience acute emergencies, and therefore, be referred to the ED [10-12]. The frequency of ED use among patients with cancer is considered high with many patients visiting the ED during chemotherapy treatment [6,13]. Despite the frequency of visits, individuals with cancer represent a small minority when compared to the total number of emergency visitors. In a study on the characteristics of ED visits by patients with cancer, the number of visits by individuals with cancer ranged between two and six percent of all ED visits [14]. This small percentage of patients likely represents a challenge for triage nurses. In addition to the infrequency of presentation at the ED, individuals with cancer suffer from a wide variety of cancer diseases. This results in a broad range of disease-specific complications that adds to the challenge of accurately identifying severe health concerns.

Other factors may also add to the complexity of effective triage of oncological emergencies. For example, cancer is dominant among the elderly population who are often affected by multiple comorbidities [15]. This may cloud the origin of the presenting problem. As well, ED visits were found to be more frequent among terminally ill cancer patients. Researchers of a study in Canada identified that individuals with cancer made the majority of ED visits in the last six months of life, with 83% visiting the ED within the last two weeks before death [16]. Gorham et al. reported that patients with advanced and metastatic cancer comprised 95% of all cancer visits. It is possible, therefore, that some patients with cancer are misidentified by associating their ED visit with the need for palliative or hospice care [13]. Acute complications are attributed to the dying process and do not get addressed appropriately [17]. However, the findings of other studies support that these presentations were true emergencies and were associated with severe complications [18].

Patel et al. explored the outcomes of telephone triage services designed to help individuals living with cancer manage their symptoms. Results indicated that 62% of individuals who made a call were referred to the ED [19]. The urgency of oncological complaints is high; in one study, more than two-thirds of patients with these complaints reported to the ED [20]. This is to be expected considering that patients usually require more ED resources such as radiologic imaging, invasive procedures, and medication administration [14].

The burden and consequences of these oncological complaints are also significant, resulting in considerable morbidities and mortality [21]. Patients with cancer have a higher admission rate than that of the general ED population [11]. Multiple studies reported an admission rate range of 60 - 90% in patients with oncology-related ED visits compared to an admission rate range in the other adult ED patients of 13 - 46% [6,11,16,22]. Cancerrelated complaints were ten times more likely to result in admission compared to other ED patients [23]. Cancer-related admission accounts for 14% of total admissions from the ED [24].

As well, individuals with cancer have high readmission rates to the hospital which is indicative of the gap between needed versus provided care. Results from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) indicated that oncological complaints were one of the top five conditions for readmission rate (CIHI, 2012). A study of patients with head and neck cancer reported 22% of patients were readmitted two to three times [25]. Patients with cancer can also experience a longer length of stay in the ED and hospital (five hours and nine days, respectively) [14]. This is expected as oncological complaints have a higher level of acuity, which requires more intervention resulting in longer management time and length of stay in the ED and hospital [23]. On average, patients stay in the hospital for nine days with 58% of the admissions staying more than one week.

Furthermore, ED patients with oncological complaints are at higher risk for death than other ED patients. On average, between 10%-12% of patients with cancer-related presentations die in the ED [25,26]. Results from a systematic review showed higher mortality rates (13%-20%) among ED patients with oncological presentations [27]. However, a lower mortality rate (1%) is noted in the general ED population [28,29]. Emergency visits were also described as a predictor of poor survival among patients with cancer [6]. For instance, the one-year overall survival of all patients with cancer visiting ED was 7.3 months [12]. Other studies reported poorer survival rates in which half of the cancer patients passed away within three months of their visit to the ED [22]. Minami et al. documented much worse survival time with a median interval from ED visit to death of 49 days [30].

The nature of oncological complaints

In the previous discussion, the high acuity experienced by individuals with cancer who seek emergency care was established. Most of these patients were admitted, experienced an extended LOS, and had increased mortality. However, by examining the presenting complaints of those patients, it was found that they appeared simple with typical signs and symptoms such as pain, nausea and vomiting, weakness, dyspnea, and fever [31].

The urgency of oncological complaints cannot be understood without examining the nature of the serious underlying problems causing these simple complaints. Although many presented with simple complaints, the underlying pathology was severe and resulted in a difficult-to-detect oncological emergency. Oncologic emergencies are described as complications of cancer or its treatment that become life-threatening or may lead to an irreversible disability [32]. Oncological emergencies can be caused by the local effects of the primary tumor, metastasis to other organs, and complications from chemotherapy or other cancer treatment [5]. Some oncologic emergencies are insidious; whereas, others manifest swiftly, causing devastating outcomes such as paralysis and death [12]. Therefore, in the next section, we review select oncological emergencies and examine the challenges of accurate triage decisions and the timely delivery of emergency care.

Emergency triage of oncological emergencies

Oncological emergencies are known to be emergent and need to be identified expeditiously to allow for prompt treatment to minimize morbidity and mortality [4,33]. Unfortunately, patients experiencing oncological emergencies are found to have longerthan- safe ED wait times even though they were suffering from severe conditions [6,9,34]. Still, EDs are designed to provide emergency care according to the clinical urgency of the health problem. For example, individuals with severe and lifethreatening conditions are supposed to be assessed and treated first [21]. To achieve this objective, different triage systems were introduced worldwide to ensure the correct identification of patients ’ health status, and therefore, provide care and treatment promptly.

In Canada, the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) guidelines are used to standardize triage decisions, making decisions more objective and justified [7]. On arrival to the ED, the triage nurse uses the CTAS guidelines to categorize the patient ’ s health acuity into one of five categories. CTAS categories represent the level of urgency of the patient ’ s presenting health condition. Clinical decisions as to the appropriate CTAS category are based on how urgently the patient needs to be seen by the ED physician. Categories are determined by the time in minutes that an individual can safely wait before medical intervention. The five CTAS categories are: 1) resuscitation (immediate lifesaving treatment by both nurse and physician), 2) emergent (up to 15 minutes to be seen by a physician), 3) urgent (between 15 and 30 minutes), 4) less-urgent (60 minutes), and 5) non-urgent (more than 120 minutes) [35].

In this section, we will review the CTAS guidelines and evaluate if select oncological emergencies were appropriately identified in the guidelines. It is essential to examine whether such documented delayed emergency care could be attributed to an inherent limitation within the triage guidelines.

Superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS): Many chemotherapeutic agents can cause cardiotoxicity and increase the risk for one of the cardiovascular oncological emergencies including SVCS and cardiac tamponade [36]. SVCS occurs when the venous circulation through the superior vena cava is obstructed. Tumor expansion can compress the superior vena cava externally with metastasis [37]. It is estimated that over 90% of cases of SVCS are attributed to malignancy. Signs and symptoms of SVCS include dyspnea, non-productive cough, hoarseness, dysphagia, facial swelling, visual disturbances, headache, and altered level of consciousness [38]. SVCS is an emergency requiring immediate treatment, but detection is difficult [39]. Because it develops gradually, SVCS is unlikely to present as a life-threatening condition [32]. Consequently, patients who present with no clear manifestations or present with non-severe manifestation such as cough, hoarseness, dysphagia, facial swelling, and visual disturbances may be triaged to the lower acuity level of ‘4’ or ‘5’. Under CTAS, patients with SVCS would only be triaged to the higher acuity level of ‘1’ or ‘2’ if they presented with severe symptoms such as altered level of consciousness.

Cardiac tamponade: This life-threatening emergency is the result of pericardial effusion, which affects 20-34% of patients with cancer [4,39]. Excess fluid accumulates in the pericardial space, resulting in increased intrapericardial pressure. The pressure can compress the heart and decrease cardiac output, resulting in tamponade [4,37]. Dyspnea is the presenting symptom for 80% of patients. Pulsus paradoxus (a decrease in blood pressure during inspiration) is another common sign that occurs in 30% of individuals with oncological pericardial effusion and 77% of those with acute tamponade [39]. Other symptoms can include chest pain, tachypnea, orthopnea, tachycardia, distended neck veins, dizziness, fatigue, and diaphoresis [37,40]. Cardiac tamponade requires timely recognition to prevent rapid fatal deterioration. The cardiac shock associated with tamponade is treated differently than traditional shocks as fluid resuscitation can be potentially detrimental, and patients usually require bedside emergency pericardiocentesis [39]. Cardiac tamponade patients present with complaints of cardiac decompensation and according to the CTAS guidelines, these patients should be triaged to an acuity level of ‘ 2 ’ . However, the gradual and chronic accumulation of fluids makes it unlikely to present with a lifethreatening condition as the body adapts to these incremental changes. This makes cancer-related cardiac tamponade more severe as the patient can collapse quickly due to cardiogenic shock. Therefore, triage nurses must have prior knowledge and be critical in their examination of all cancer patients with cardiac manifestations to ensure the appropriate triage of this life-threatening oncological emergency.

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS): TLS is another vague oncological emergency. TLS can present insidiously but can be associated with significant morbidities and mortality if not recognized early and treated appropriately [41,42]. TLS is a metabolic emergency resulting from lysis of tumor cells leading to the release of tumor cellular contents into the systemic circulation [43]. The kidneys cannot compensate for the large volume of toxins that need to be filtered from the body [37]. The subsequent metabolic abnormalities include hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, hyperuricemia, and acute kidney injury. These metabolic abnormalities can lead to life-threatening manifestations such as cardiac dysrhythmias and neurologic complications [44].

TLS can occur spontaneously but is usually associated with the induction of chemotherapy or radiotherapy [33]. However, all types of cancer treatment can cause TLS [45]. The clinical manifestations can include vague signs and symptoms such as diarrhea, lethargy, muscle cramps, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and oliguria [37]. Diagnosis is dependent on the laboratory values including a complete blood cell count and a metabolic panel of liver and kidneys [46]. Emergency management includes measures to reduce the risk of renal impairment and treatment of metabolic abnormalities with fluid resuscitation to increase excretion of the extra metabolites [43,47].

Tumor lysis syndrome can be hard to triage appropriately and a patient can receive less priority according to the CTAS guidelines. Patients can earn a higher triage acuity score if they present with fatal cardiac arrhythmias, but early detection at triage is unlikely because an ECG is required, and this is not usually performed during triage assessment. Delayed identification can have severe, life-threatening complications with significant morbidities and mortality as previous reports support [41,42].

Febrile Neutropenia (FN): Bone marrow suppression is an expected side effect for many of the chemotherapeutic regimens, and specifically, neutropenia is the most profound clinical consequence. All chemotherapeutic drugs have a cytotoxic effect and are capable of inducing neutropenia to various degrees [36]. Fever and infection secondary to neutropenia are the most severe, life-threatening complications of cancer treatment and are a significant cause of hospitalization and death [22,48]. Patients with cancer are four times more likely to present with severe sepsis from neutropenia compared with non-cancer patients (2.1% vs. 0.5%) [14]. Cancer patients have double the risk of mortality if presenting with sepsis at the ED as they may be experiencing a subtle but severe underlying infection [49].

Fever is one of the most common reasons for ED visits among patients with cancer [27]. Fever may be the only presentation for FN, but many patients are afebrile [50]. Fever as a cancer-related ED presentation is likely to be associated with neutropenia (45%), sepsis (26%), and pneumonia (14%). Reports of ED care of patients with fever demonstrated the urgency of this complaint as more than 83% of patients with fever were admitted to the hospital [12,27]. Emergency admissions of cancer patients were found to be significantly associated with the complaint of fever [51]. Not all neutropenic patients will present with a fever, nor does all fever indicate febrile neutropenia (FN). However, all cancer patients presenting to ED should be queried for FN until ruled out with proper examination [36].

The risk of FN with chemotherapy is about 17%, and the risk rises with repeated chemotherapy cycles [6,52]. Others reported a higher rate of FN occurring in half of the patients receiving chemotherapy [53].FN may result in significant clinical implications such as delaying and discontinuing chemotherapy and is associated with considerable morbidity, mortality, and costs [46]. One study documented the burden of hospitalized FN in relation to hospital mortality (14%), length of stay (13 days), and costs ($22,800) [48]. FN is the cause of death in 4% to 30% of patients with cancer [54]. Empiric antibiotics should be initiated promptly as delayed initiation of antibiotics can be associated with increased mortality due to rapid progression to septicemia [36,55,56].

The CTAS guidelines do identify the urgency of FN but only if the patient has a high fever at triage. The guidelines recommend the assignment of a triage rating of ‘2’ if the patient has a fever and is immune-compromised or is receiving chemotherapy treatment [35]. Moreover, fever in FN is defined as “ a low neutrophil count of 1.5 × 109/L and single oral temperature measurement of >38.3°C or a temperature of >38.0°C sustained over one-hour period ” [50]. Nirenberg et al. found that the majority of FN patients experienced fever for a mean time of 21 hours before seeking emergency care. However, patients may not have a fever when presenting at triage which renders them to be assigned to a less urgent triage category [34].

In reviewing studies examining triage implementation among patients with oncological emergencies, findings confirmed that this patient population was more likely to be assigned a lower acuity triage score. For example, an Australian ED study of newly diagnosed patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy showed that 79% of patients were assigned an acuity rating that was lower than recommended by the Australian Triage Scale guidelines [8]. Similarly, a Canadian study of patients with emergency-related oncological complaints demonstrated that two-thirds of patients were assigned to lower triage acuity ratings (less urgent) [57]. Furthermore, cancer patients and their families perceived that their oncological presentations were not given accurate ratings at triage [58]. These perceptions were accurate as patients have been inappropriately delayed in receiving needed care [6,9,34].

The standard of care is to treat FN as an oncologic emergency; patients are expected to be seen right away to commence prompt delivery of the necessary treatment [55]. Although fever is an essential sign of infection, lack of fever does not necessarily exclude it [36]. The FN clinical guidelines recommend that afebrile neutropenic patients who have new signs or symptoms suggestive of infection to be evaluated and treated as high-risk patients [47]. Furthermore, the presence of fever does not guarantee proper triage. For instance, an Australian study of 200 neutropenic episodes illustrated that 1/3 of patients were inappropriately assigned to the less urgent triage category to be seen in a time that is far longer than what is considered clinically appropriate [56]. A study of ED oncological complaints reported that the deceased group of patients were more likely to have been triaged to less urgent categories where they witnessed longer wait times and ED length of stay [56]. For patients with FN, timely care is very important as the time to initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the most reliable predictor of outcome among patients with early signs of sepsis, with around 8% drop in their survival for every hour of delay [59]. The CTAS guidelines allow for prompt treatment of patients with fever. The recommendations are to allocate those patients into the second acuity triage rating, enabling them to be seen by a physician within 15 minutes. However, not all FN patients have a fever at triage, meaning a lower rating is allocated; patients often experience significant delays. Furthermore, the implementation of the CTAS seems inappropriate in most of the occasions where two-thirds of patients with FN who had a fever at triage were allocated to a lower than appropriate triage acuity rating [60].

The ED remains an accessible place to receive timely treatment with the availability of multiple and comprehensive laboratory and radiological examinations and a provision of coordinated and multidisciplinary care that is adequate for the complex conditions of those patients [61]. However, with large volumes of patients and periodic overcrowding, the accuracy of ED triage becomes more critical as inaccurate triage can result in longer delays [22]. Timely treatment of oncology patients in the ED can dramatically enhance their quality of life and improve their survival [62]. ED health professionals, and especially triage nurses as the gatekeepers of emergency care, should have a strong knowledge base regarding oncological emergencies and be thorough in their examination of patients with these conditions [32]. Oncologic emergencies may be insidious and may have rapidly deleterious effects [63]. Knowledge of the signs and symptoms of these emergencies will enable triage nurses to accurately differentiate the urgency of the different presenting complaints [64]. Education that prepares triage nurses to better understand the complexity of the symptom presentation and the needed care for patients with different oncological emergencies is essential [65]. There is strong evidence that adequate knowledge is the most crucial element in making accurate triage decisions [66,67]. Knowledgeable health providers, in partnership with patients and families who are well-informed about the risks and complications of oncological emergencies, can ensure the best care possible.

The review of the CTAS guidelines has identified some limitations concerning clear guidance for triage nurses. Although revisions have been implemented and the reliability of the CTAS tool has improved, the guidelines are designed to be generic and cannot address every health situation [68]. Febrile neutropenia is an excellent example of the additional supports needed at triage to accurately determine the patient’s health status. The FN clinical guidelines, for example, identify afebrile neutropenic patients as high-risk [50], demonstrated by a significantly higher 30-day in-hospital mortality [69]. Accordingly, the CTAS guidelines must be updated to reflect such up-to-date evidence. Point of care testing at triage can enable the early recognition of neutropenia and prevent any inappropriate delay among afebrile neutropenia patients.

Also, triage nurses need to be well informed about and convinced by the scientific evidence in order to follow the guidelines more closely [65]. Some studies highlighted discrepancies in triaging cancer patients even when they present with FN [6,9,34,70]. A similar discrepancy was evident among acute myocardial infarction patients [71]. Education strategies should address the need to objectify the triage process and to promote skill and ease in those using the guidelines. This specific recommendation was made by the establishers of the CTAS guidelines, that is, to properly use and implement the CTAS guidelines in order to make an accurate assignment of triage levels. Such a desire for objectivity in triaging patients has led to the development of a computerized version of emergency triage (e-CTAS) [68]. However, we used a similar version to this e-CTAS using the 2012 complaint-oriented triage (COT), but we failed to prioritize the urgency of these oncological emergencies using this tool.

Other strategies to improve recognition of oncological emergencies were also found helpful such as the implementation of fever alert cards (FACs). Kapil et al. evaluated FACs as a communication tool to decrease TTA in patients with FN who present to the ED. The implementation of FACs helped in improving FN recognition with a higher percentage of patients obtaining a correct CTAS score [72]. This can be combined with clinical protocols and pathways to fast-track patients with certain conditions. For example, the Febrile Neutropenia Pathway (FNP) was introduced to one ED and was found helpful in reducing time to antibiotics by almost two thirds [73]. However, we could not allocate similar strategies to improve recognition or timely treatment in the ED for other oncological emergencies described earlier. Finally, EDs should follow the CTAS guidelines recommendations in monitoring the time objectives set by the guidelines and tailor their resources to meet these benchmarks [69]. Routine system monitoring and benchmark analysis of wait times for patients in different categories can be considered necessary. However, studies with such main objective are of rarity or can be underreported [74,75].

In this paper, we reviewed the underlying reasons for patients with cancer to seek emergency care. We demonstrated that these ED presentations and subsequent hospitalizations are a necessary service for individuals with cancer and are not avoidable. Patients with cancer have a higher acuity compared to many other ED patients and they experience high rates of hospital admission and increased risk of death. However, most cancer patients suffer significant delays when seeking emergency care even when they presented with oncological emergencies. Many of these emergencies have time-sensitive interventions, making it crucial to establish the correct identification at triage to enable the prompt delivery of appropriate care. Because many of these complaints can be subtle and nonspecific accurate identification often takes time. This poses risk to those experiencing oncological emergencies and suggests that the CTAS guidelines need to be strengthened to better represent the urgency of these life-threatening conditions.

Based on our review, we suggested a couple of refinements to the guidelines to increase their sensitivity in detecting oncological emergencies. Also, strategies were identified to improve compliance in using the guidelines. We emphasized the role played by education to prepare the patients, families, and the triage nurses to better understand the complexity of oncological emergencies, their signs and symptoms, and the needed emergency care. Finally, routine system monitoring and benchmarks analysis were highlighted as one approach to meet the time objectives set by the guidelines.

This work was supported by Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Citation: Alsharawneh A, Maddigan J (2020) Do the Canadian Triage Guidelines Identify the Urgency of Oncological Emergencies? J Cancer Res Immunooncol. 6:121. DOI:10.35248/2684-1266.20.6.121.

Received: 13-May-2020 Accepted: 27-May-2020 Published: 03-Jun-2020 , DOI: 10.35248/2684-1266.20.6.121

Copyright: © 2020 Alsharawneh A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sources of funding : This work was supported by Memorial University of Newfoundland.