Journal of Ergonomics

Open Access

ISSN: 2165-7556

ISSN: 2165-7556

Research Article - (2021)

Cognizant of the special needs of indigenous people in the Philippines, the Republic Act No. 8371 of 1997 was established to promote and protect their rights. Over the years, a number of community organizing efforts for the improvement of these communities were conducted by stakeholders from the private and public sectors. However, resistance has been reported due to poor understanding and integration of these indigenous populations' varied cultures and traditions. This study aims to describe the predominant principles and frameworks used for community organizing among indigenous people. Specifically, it seeks to propose a community organizing approach that is culturally sensitive and appropriate for indigenous communities in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas in the Philippines. A systematic review was conducted on four databases (PubMed, Science Direct, Research Gate and Google Scholar) by four independent researchers. Inclusion criteria involved studies about community organizing protocols in the Philippines, published in peer-reviewed journals from 2010-2020, and written in the English language. Assessment of the quality of included studies was done using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist, and narrative synthesis was employed to summarize and report the findings. Thirteen studies met our inclusion criteria out of a total of fifty-five articles searched. Based on the evidence, our proposed approach builds on groundwork, indigenous capacity building, community participation and ownership, mobilization, and sustainability. We highlight the emphasis of harnessing indigenous knowledge and participatory monitoring and evaluation to involve them in all steps of the planning and decision-making processes. Furthermore, we distill tools and methodologies that could strengthen and precipitate successful community organizing endeavors.

Community organizing; Community participation; Indigenous people; Indigenous filipinos

The Philippines is a culturally diverse country with various ethnolinguistic groups that denote genealogical, paternal as well as maternal lineage to any of the country’s group of native population [1]. According to the 2015 population census, Indigenous People (IP) in the Philippines constitutes 10%-20% of the national population of 100,981,437. The estimated 14-17 million IPs belong to 110 ethno-linguistic groups, which are mainly concentrated in Northern Luzon (Cordillera Administrative Region, 33%) and Mindanao (61%), with some groups in the Visayas area [1].

Republic Act 8371 [2], known as “The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997”, states that Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous People are: “a group of people or homogenous societies identified by self-ascription and ascription by others, who have continuously lived as an organized community on communally bounded and defined territory, and who have, under claims of ownership since time immemorial, occupied, possessed and utilized such territories, sharing common bonds of language, customs, traditions, and other distinctive cultural traits, or who have, through resistance to political, social and cultural inroads of colonization, nonindigenous religions, and cultures became historically differentiated from the majority of Filipinos.”

In the Philippines, the IP communities remain among the poorest and most disadvantaged peoples. Because they have retained their traditional pre-colonial culture and practices, they were subjected to discrimination and few opportunities for major economic activities, education, or political participation. As a result, they have been resistant to development and information, thus have been driven to Geographically Isolate Disadvantaged Areas (GIDAs) with no adequate and accessible basic services.

To recognize this diversity, the Philippine Constitution signed Republic Act No. 8371 of 1997, which seeks to identify, promote, and protect the rights of the IPs. These include the Right to Ancestral Domain and Lands; Right to Self-Governance and Empowerment; Social Justice and Human Rights; and the Right to Cultural Integrity [3], which is in line with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

Despite the international and national recognition of the inherent rights of indigenous peoples, IP communities were subjected to historical discrimination and marginalization from political processes and economic benefits. The Report on the State of the World of Indigenous Peoples, issued by the United Nations Permanent Forum on indigenous issues in January 2010, revealed that IPs' traditional livelihoods were threatened by extractive industries or substantial development projects. Still, they continued to be over-represented among the poor, the illiterate, and the unemployed. While they constitute approximately 5 percent of the world’s population, IPs make up 15 percent of the world’s poor, comprise about one-third of the world’s 900 million destitute rural people, continuously suffer disproportionately in areas like health, education, and human rights, and regularly face systemic discrimination and exclusion [3].

In the Philippines, the National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) and Department of Social Welfare and Development were mandated to implement programs, projects, and provide services through engaging the indigenous people in a meaningful development process where there is full recognition of their capacity to strengthen their own economic, social, and political systems [4]. As a result, the IP sector has a broad spectrum of active support groups and organizations from government, academe, nongovernment organizations, international groups, and churches. In addition, the enactment of IPRA paved the way for the growth of IP support groups that provide assistance on policy advocacy, education, community development, and poverty alleviation programs.

However, despite the growing number of NGOs and programs for IP communities, conflicts among the community members continuously rise. In an attempt by the State to Enforce Developmental Projects, there was growing resistance from IPs due to their own indigenous governance, which struggles to preserve their own customary laws and traditions. There were also instances wherein NGOs with little or no exposure to IPs cultures have generated conflicts because of insufficient program analysis. In addition, pressure from funding donors who have tight project schedules and are pushed to produce outcomes has resulted in shortcuts, thus marginalizing critical community processes [5].

This review aims to describe studies that have meaningful participation of IP communities and explore ways to tailor the community organizing principles to be more culturally sensitive in improving IPs' access to essential social services such as health, nutrition, sanitation, and formal and non-formal education. Culture-sensitive facilitation is defined as awareness and acceptance of cultural differences on the part of the facilitator that allow them to engage with indigenous people in a manner that is appropriate and responsive to their customs, traditions, values, and beliefs [4]. This regards IP communities not just mere passive recipients or beneficiaries but as active partners in the program. The community organizing principles presented may help community organizers, NGOs, and even government programs to provide a more sustainable implementation of the activities. The study focuses on the IPs in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas, particularly those with: no or limited opportunities for development, no or limited access to social services, no access road or hard to reach areas, and insufficiency of food security.

Based on a thorough review of research evidence, the proposed community organizing approach can be applied for the implementation of health programs and interventions that are culturally sensitive and responsive. This would support the paradigm shift in participation practices that value community input while minimizing risks of unintended harms and consequences for indigenous communities.

Search strategy

The study utilized a systematic review design to describe the approaches to community organizing for IPs in GIDAs in the Philippines. The researchers independently conducted elementary analysis on four online databases namely: ResearchGate, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar to identify relevant and published studies. An elementary search on Titles and Abstracts identified a range of available evidence on the community organizing frameworks or protocols implemented for IPs in local and international settings. Keywords used were: Community organizing and Philippines, Community participation and Philippines, Community engagement, Community organizing for Indigenous People, Indigenous people and planning, Indigenous people in Asia and Philippines, Indigenous Planning Framework, Community Mobilization, Community Participation, Rural development, Collective Action. In addition, the researchers reviewed the selected articles’ references in order to identify additional studies or reports not retrieved by the preliminary searches (reference by reference).

Study selection

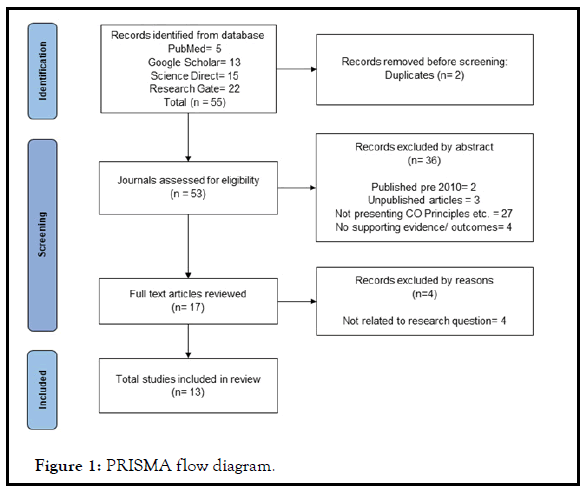

This systematic review utilized the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram.

After independently searching the aforementioned databases, a total of 55 journal articles returned from the keywords used. Data cleaning then commenced to remove duplicates leaving 53 articles to assess for eligibility. Using the inclusion criteria on the titles and abstracts, about 36 articles were removed as they did not fit with the parameters such as being published pre-2010, articles from non-peer reviewed journals, those that did not employ community organizing principles, and those without supporting evidence/ outcomes. This resulted in 17 full-text articles that were screened and reviewed. These were further narrowed down to remove those that were not relevant to the research objective. A final count of 13 journal articles was included in the final review.

Eligibility criteria

All studies searched from the identified databases that showed concepts of community development, organizing, and mobilization targeting the local communities such as indigenous people and geographically isolated disadvantaged areas, were included in the preliminary analyses. The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to identify the eligible articles to be reviewed (Table 1).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

After the initial screening, full-text of the study was retrieved and was subjected to quality assessment. Data were extracted from all research papers that met the inclusion criteria. The following data were extracted and analyzed using the following criteria: first author, year of publication, title of the study, country, target population, intervention, comparison, community organizing principles used outcome, and study design.

Quality assessment

After extracting the papers which met the eligibility criteria, assessment of the quality of each paper was then carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist. This tool allowed the researchers to gauge the clarity of each article’s study objectives, the quality of the methodology, research design, data collection and analyses, ethical considerations, whether there was a clear statement of findings, and the overall value of the research.

Evidence synthesis

In order to summarize and explain the findings of the multiple studies appraised, narrative synthesis was employed. This was done by first developing a preliminary synthesis of the topic of the papers (using the PICOS parameters of Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study Design), exploring relationships within and between studies to determine patterns and trends, and assessing the robustness of the synthesis by considering the methodological quality of the papers being reviewed (such as the quality and quantity of the evidence base it is built on). The researchers held frequent meetings to discuss the findings from the articles they independently assessed.

Quality of the included studies

Most of the included studies were able to pass the parameters set by the tool (n=10) with three studies that were not able to fully satisfy one or more parameters of quality (Tables 2 and 3) [6-18].

| Publication (1st Author and Year) | Clearly focused question? | Research design appropriate for its aims? | Data collection addresses the research issue? | Literature review extensive? | Research is valuable? | Rigorous data analysis? | Clear statement of the findings? | Can be applied to the local population? | All important outcomes considered? | Benefits worth harms and the costs? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibanez, J. (2014) [6] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Brady, S. et al. (2014) [7] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Dattaa, R. et al. (2014) [8] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ibanez, J. et al. (2016) [9] |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Amparo J.M. et al. (2020) [10] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Oetzel J. et al. (2020) [11] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jemigan V.B. et al. (2015) [12] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Subica A.M et al. (2016) [13] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Calderon, M.et al. (2015) [14] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chapin, F. et al. (2016) [15] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chowdhooree, I. et al. (2020) [16] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Labonne, J. et al. (2011) [17] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ruszczyk, H. et al. (2020) [18] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 2: Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) quality assessment of included studies.

| Publication (1st Author and Year) | Title | Country | Target Population | Intervention | Comparison | Community Organizing Principles Used | Outcome | Study design |

| Ibanez, J. (2014) [6] |

Developing and testing an Indigenous planning framework |

Philippines | Five Indigenous villages who own native titles over ancestral domains in Arakan Valley, North Cotabato |

Proposed process framework that is shaped by Indigenous community planning (VIP) model which is an amalgamation of Radical Planning, Indigenous planning and Strategic Planning |

Comparison between the ADSDPP (NCIP Admin diagnosis Order No. 1, Series of 2004 and in practice) and Village-based Indigenous Planning frameworks were compared | 1. Community 2. Priority setting 3. Rural livelihood analysis 4. Social planning 5. Participatory evaluation | The proposed process framework was effective and very satisfactory compared to the existing planning processes of other NGOs or the government | Experimental-Exploratory |

| Brady, S. et al. (2014) [7] | Understanding How Community Organizing Leads to Social Change: The Beginning Development of Formal Practice Theory | United States of America | 10 participants with expertise in community organizing from two major traditions of organizing: the civil rights and union organizing traditions | Explored the intersection between community organizing, consciousness rasing, social justice, and social change | NIA | 1.Reflecting on Motivations 2.Community Building 3.Organization Plan 4.Community Mobilization 5.Outcomes Assessment |

The proposed dialectical empowerment model of community organizing was able to move forward the development of formal practice theory. |

Qualitative |

| Dattaa, R. et al. (2014) [8] | Participatory action research and researcher's responsibilities an experience with an indigenous community | Bangladesh | Laitu Khyeng indigenous community CHT Bangladesh | Relational PAR | NIA | 1. Empowering participants 2. Knowledge ownership 3. Relationality 4. Holism 5. Centering on indigenous voices | Through the application of relation of PAR the researchers were able to explore how the Laitu Khyeng indigenous community has been dreamind, hoping, and working hard to rebuid their traditional forest water management | Experimental-Exploratory |

| Ibanez, J. et al. (2016) [9] | Planning sustainable development within ancestral domains: indigenous people's preceptions in the Philippines | Philippines | Eleven native title holgers from 10 ethnic groups in Mindanao | Proposed Indigenous Planning frame work | Desired attributes of a good Indigenous planning process based on focus group discussions and participant ranking and scoring of best practice standards derived from the literature | 1. Desired Planning Attributes: Focus Groups and Ranking 2. Participatory planning 3. Planning and External support 4. Planning and Indigenous Knowledge Systems 5. Planning, tribal identity and ethnic accommodation | Findings from this study highlights the human, financial, pysical, natural, social and cultural elements that should be considered when making Indigenous plans. The study illustrates the importance of direct participation of Indigenous people in the planning process in order to promote Indigenous ownership and benefits all Indigenous people equitably. | Descriptive Qualitative |

| Amparo, J. M. (2020) [10] | Women's Economic Empowerment and Leadership (WEEL) Project to Enhance the Modified Conditional Cash Transfer for Indigenous People (MCCT-IP) and (RCCT) in (GIDA) | Philippines | IPs in GIDAs (Benguet, Zambales, Camarines Sur, Antique, Negros Oriental, Bukidnon, Agusan del Sur, Zamboanga del Norte) | 4K4W package of intervention | N/A | 1. Community profiling 2. Situational analysis 3. Capacity building of Ips in GIDA 4. Strengthening implementation of interventions through the engagement of local IP leaders | The 4K4W became an avenue for policy advocacy, consensus building, and rural enterprise development for indigenous women and their commmunities. Integration strengthened the call to promote sesitivity and responsiveness in terms of gender and culture across the program phases and componenets. | Experimental-Exploratory |

| Oetzel, J. et al. (2020) [11] | A case study of using the He Pikinga Waiora Implementation Framework: challenges and successes in implementing a twelve-week lifestyle intervention to reduce weight in Maori men at risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity | New Zealand | Maori men (member of a Polynesian people of New Zealand) | Partnership involving Maori community providers to develop a twelve-week lifestyle intervention to reduce weight in Maori men at risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and obesity | Use of peer or community health worker for support | Involvement of stakeholders all throughout the process | The co-design process resulted in a strong and engaged partnership between the university team and the provider albeit some partner organization drop outs just after the initial implementation phase. | Cohort Study |

| Jemigan, V.B. et al. (2015) [12] | The Adaptation and implementation of a Community-Based Participatory Research Curriculum to Build Tribal Research Capacity | United States of America | American Indian/Alaska Native communities | Implementation of Community-Campus Partnerships for Health(CCPH) curriculum (2-year intensive training) | N/A | 1. Invlovement of stakeholders all throughout the process 2. Providing for equal oppurtunities in community participation 3. Individual and community empowerment 4. training and capacity building 5. Partnership development | Engaging in CBPR can build the capacity and infrastructure of tribal nations to conduct research by requiring tribes to formalize research partnerships and protocols and develop tribal research agendas; Best practise examples of trainings delivered for and by AI/AN incorporate Indigenous knowledge and practices. | Case study |

| Subica, A.M. et al. (2016) [13] | Community Organizing for Healthier Communities: Environmental and Policy Outcomes of a National Initiative | United States of America | Ethnocultural groups | N/A | N/A | 1. Social investigation 2. Developing the ground work 3. Identifying shared health concerns, and engaging in critical dailogue about its underlying causes 4. Community meetings and outreach 5. Social mobilization | Policy wins Environmental and policy solutions to address childhood obesity and promote healthy living | Mixed method |

| Calderon, M. et al. (2015) [14] | Community-Based Resource Assessement and Management Planning for the Rice Terraces of Hungduan,Ifugao,Phillippines | Phillippines | Ifugao farmers | Community-Based Resource Assessement and Management Planning | N/A | 1.Community dignosis 2.Capacity building and training 3. Involving stake holders in all steps of the planning process, thereby allowing them a sense of "ownership" and responsibility in their decisions and implementation | The approach promoted effective participation, successful application of indigenous knowledge empowerment, and development of political confidence and expertise of the farmer-participants. | Qualitative |

| Chapin, F.et al.(2016) [15] | Community Empowered Adaptation for Self-Reliance | United States of America | Alasaka Native communities | Community Empowered Adaptation planning | N/A | 1. Creation of a boundary organization that linked communities with the experts from the university and officials from concerned agencies. 2. Community wide meetings 3. Relationship building and culturally - appropriate interactions with communties | Collaborative learning through action research allowed a transdisciplinary take on tackling issues in the community . The study showed that power, knowledge, and wisdom can be shared through diagloue that integrates " inreach" (by locally in formed adaptation effeorts and "outreach" (from top-down adaptation programs ). | Action research |

| Chowdhooree, I.et al.(2020) [16] | Scopes of community Participation in Development for adaptation: Experiences from the Hoar Region of Bangladesh | Bangladesh | Two settlements in the Hoar Region | NGO-driven development projects and their planning process | N/A | Formation of a community committee to discuss matters of concern albiet done only as a symbol/token since the ideas of the people were not fully addressed due to the close-mindedness of the NGOs. | Although the NGOs had resonable agendas for the target community they did not always involve the community members in the planning stages of any project and only inform them once decisions have been made. | Case study |

| Labonne, J. et al.(2011) [17] | Do Community-Driven Development Projects Enhance Social Capital? Evidence from the Philippines | Philippines | Low income and geographically isolated and disadavantaged areas | Community driven development project | N/A | 1.Election of village leaders to organize the community 2. Conduct of Village meetings in the planning and decision making of projects 3.Employments of facilitators to ensure community particip[ation and follow-up. They also act as community coordinators who also help mobilize communities. | Results of the study indicated that CDD operation led to changes in the village-level social and institutional dynamics. The creation of project proposals themselves required substantial input, interaction, and participation among the inhabitants of the community. | Survey |

| Ruszczyk, H. et al. (2020) [18] | Empowering Women Through Participatory Action Research in Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction Efforts |

Nepal | Kathmandu Valley | Community- based disaster risk reduction (CBDRR) | 1 urban and 1 rural neighborhood | Provision of training programs for the women to be able to access resources, increase their knowledge and hone skils to be empowered to respond and manage disaster risk and reduction in their areas. | The PAR sucsessfully mobilized women from both communities and increased their sense of responsibility and capacity in local disaster related activities. | Comparative case study |

Table 3: Characteristics of the included studies.

Proposed community organizing approach for imdigenous people in the Philippines

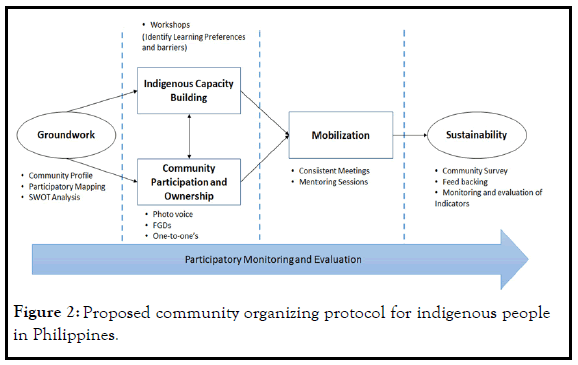

In this systematic review, the researchers were able to identify community organizing principles used in programs directed for the indigenous population. The researchers categorized the different principles to the following stages: Pre-entry, entry, organization building, strengthening, and turn over phase. The researchers proposed a community organizing framework from the themes and best practices that surfaced during the review. Methodologies and evaluation plans for each phase of the community organizing process were also identified. Building on knowledge presented, this paper contributes to the gaps in existing framework used for community organizing among the IP population in the country. Figure 2 presents the proposed Community Organizing Protocol for Indigenous People (IP) in the Philippines.

Figure 2: Proposed community organizing protocol for indigenous people in Philippines.

Groundwork

The groundwork is the preparatory phase for community organizing. This constitutes pre-work activities that set the foundation of reform strategies before engaging with the community. The reviewed studies documented groundwork activities such as conduct of community diagnosis, community profiling, and social investigation to describe the system. The study of Jemingan, et al. also suggested the involvement of stakeholders and research partners such as the academe in the community organizing process [12].

Groundwork activities are critical because it examines the local context and conditions in the village using the subjects: people, ancestral domain, and resources [6]. Some literature also stated that learning the local culture and governance structures as well as identifying respected leaders and key decision makers who allocate resources is also essential before entering the community [19].

Indigenous leadership structures should be identified. The acceptance and involvement of local leaders and potential leaders as well as knowing how to deal with them are critical in mobilizing the community. Leaders should also be approached respectfully in accordance with local cultural practices [19].

The paper also suggests that there should not be a pan-indigenous understanding. There must be a full recognition of the diversity of the indigenous people and understanding of local history, cultures, powers and resources [20].

Community organizers can make use of secondary data sources as well as Participatory Research Appraisal (PRA) tools to examine the setting and power levels within the community [6].

Indigenous capacity building

Indigenous capacity building is necessary to prepare the community members. Organizers must ensure that the community has the required skills set and be provided with mentoring and coaching sessions to guide them in the process. This paper was able to identify activities such as community building, empowering participants, and training as capacity building activities in the community organizing process.

Provision of skills training and inputs to indigenous communities may pose challenges. A study conducted in Canada identified that indigenous people have learning preferences such as being visual, spatial, and being comfortable in a small learning group. Some learning barriers identified are namely language, and learning difficulties due to illiteracy [21].

The researchers categorized this step as part of the cognitive intervention in the community organizing process. This is tailored with a behavior-centered intervention specifically in increasing the ownership of the community members.

Community participation and ownership

To address the root causes of health and social problems in the community requires a deep partnership within the community members. Meaningful engagement can take place through members of the community understanding their personal role and counterpart in the development process and success of the program. However, participation is not enough to ensure complete community engagement, a shared vision is required to build commitment.

Grassroots community organizing groups may build interpersonal relationships among participants through awareness-raising activities such as photo voice, focus group discussions, and semi structured conversations between two people also known as oneto- ones. Planning and forming of action plans should be done with the community is instrumental in ensuring that integration of indigenous knowledge aligns with culturally safe intentions, and to avoid the appropriation of knowledge [20].

Mobilization

After building the capacity of the core group, this phase entails the actual implementation. Based on the reviewed studies, community facilitators or coordinators play an important role in ensuring the success of community participation during project implementation by helping in mobilizing communities as well as in ensuring adequate representation [16,22]. The facilitators motivate the community to willingly agree in the fulfillment of the project and also encourage the community to participate in decision making.

Moreover, consistent meetings were found to be beneficial in ensuring proper management and execution of a project/program/ intervention in the community [16]. Project planners were able to closely monitor the implementation during site visits. These frequent visits also helped in increasing participation among residents in the community. Regular community meetings may also promote reciprocal learning and establish trust and respect [19]. Aside from the consistent meetings, open communication with project planners also aid in the success of organizing indigenous communities. Transparent communication with and within the community (e.g. community-wide meetings) may increase the likelihood that a broad spectrum of issues and views would be discussed [17]. This is also one of the steps included in the eight-step approach aligned with the CARE model which is to facilitate continued, multimethod communication. Interpersonal communication is often the most important means of information sharing at the community level [19].

A study conducted in Bangladesh also presented various methods used in engaging community participation in indigenous communities that were aligned with the Participatory Action Research (PAR). Data analysis was emphasized as one of the significant parts of the study (aside from sharing research results), wherein the elders and knowledge holders also took part in the sharing of codes in which their core values, beliefs, and spiritual practices were also considered in the process [15].

Public health practitioners can use these tools and methodologies to ensure success in their community organizing efforts.

Sustainability: This phase focused on maintaining the coalition, as well as the implemented programs or projects in the community. Based on the reviewed studies, stakeholders should be involved all throughout the process so that they may feel a sense of “ownership” and are accountable for the success of the program/intervention [8]. One of the critical factors identified in the success of indigenous community-managed programs is through facilitating community ownership and control. This can be embedded in the communitymanaged programs by forming local indigenous management bodies and formal agreement with partner organizations [20].

In another study reviewed, ‘sharing data analysis was also found to be useful in maintaining programs in the community [15]. Dissemination of the findings to the key stakeholders is necessary for them to understand the context and thereby sustain its implementation [14]. One of the community organizing principles involves consciousness-raising through experiential learning [12]. Data sharing is a means of increasing awareness and motivation among people for them to sustain what has been introduced to the community.

In addition, monitoring and evaluation is also essential in the continuity of the programs/projects. Tracking progress, successes, failures, and costs are also critical for sustainability [19]. Results should also be regularly communicated to the beneficiaries and partners so that these will be incorporated in the strategic action planning with the community [10]. Thus, there is a need to establish indicators and a monitoring scheme [6,7]. Moreover, formation of a core working group is also needed in this phase since they are able to conduct the evaluation and therefore, help in ensuring its continuity [16,17].

Participatory monitoring and evaluation: Among the articles reviewed, only the study conducted by Ibanez explicitly stated participatory evaluation [6]. Brady, et al. suggested outcomes assessment [23]. The researchers identify the inclusion of an evaluation protocol as a vital component in the community organizing framework. The proposed framework makes use of the Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation (PM and E) as the monitoring and evaluation approach. PM and E is defined as applied social research that involves a partnership between trained evaluation personnel and practice-based decision makers, organizational members with program responsibility, or people with a vital interest in the program [24]. This approach is essential for evaluating community organizing programs as this build on the involvement of the community in every step of the process. A comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system should enable the organizers, community members, and leaders to learn which strategies work and what needs to be improved.

The PM and E process will be able to cover all phases of the organizing process. This includes,

1. Participatory appraisal

2. Participatory planning and project design

3. Participatory development of baseline indicators

4. Participatory baseline data collection

5. Participatory monitoring and evaluation plan design

6. Participatory implementation

7. Participatory monitoring and review

8. Participatory evaluation

9. Feedback and participatory decision making [25].

All steps are done in consultation and collaboration with organizers, funders and the community beneficiaries, deciding what will be monitored and how the monitoring will be conducted. Together, they analyze the data gathered through monitoring and assess whether the project is on track in achieving its objectives. Participatory monitoring enables project participants to generate, analyze, and use information for their day-to-day decision making as well as for long-term planning.

Some relevant studies might have been missed in the review because they were published in languages other than English. There was also no funding utilized thus, the researchers were limited to searching open-access scientific databases which may not capture other peer-reviewed journals. No primary data gathering and no face-to-face interview were done during the course of the research. All methods, techniques, and communication were done online by the researchers.

The community organizing approach presented in the review are best recommended practices, nevertheless this should still be reviewed upon by the National Commission on Indigenous People in order to verify that every phase is in the light of the IPRA. Though most of the frameworks used by the articles were applied in a study population, the proposed community organizing approaches have yet to be tested in indigenous communities.

The shortcomings of the existing framework used in the Philippines by the government as discussed in the earlier sections can be minimized or supplemented by the proposed community organizing protocols. The indigenous planning framework has a wide range of scope and uses a needs-based approach wherein it mainly focuses on the deficit of the community. Although the IP’s concerns are considered in searching for promising opportunities, the problem-based approach can overemphasize what the community lacks in order to attract outside aid. This may affect program implementation and sustainability especially if the problems are already addressed or the organizers have already achieved their goals which are why the researchers have recommended an assetbased approach in community organizing protocols in order to empower the community through collective engagement and have a control over their own resources.

The framework was divided into five domains: Groundwork, indigenous capacity building, community participation and ownership, mobilization, and sustainability. Groundwork is a very essential process in Indigenous communities and was incorporated in the Indigenous People framework as a situational analysis step. Various methods and tools such as stakeholder analysis were suggested in the existing IP Framework in order to have an inclusive and responsive project. In this study, there are a wide range of tools identified in the Groundwork phase that have been proven effective in analyzing the conditions of Indigenous communities. This phase analyzes the different social and cultural structures and understands the land and natural resources that are linked to their identities and livelihoods which is essential in establishing rapport in the IP community.

The study also highlighted the need to focus on the first two phases of the community organizing process which is community participation and capacity building in order for the intervention to be socially acceptable. Since the IP communities are governed with their own indigenous institutions, appropriate consent is necessary before any activities can be taken within their ancestral domains. The integration of the findings obtained in the first two phases within the indigenous structure of social preparation activities are important as an entry point for community organizing in IPs. It is important to work within the social structures and system thus; the community should have a full understanding of the project to increase acceptance and support of the community organizing process.

On the other hand, methods such as focus group discussions, photo voice, and common place books are uniquely designed for IPs so as to promote engagement while overcoming the language barriers among the community. Participation of indigenous groups is integrated in all phases of community organizing in order to establish a strong sense of ownership of the project. Monitoring and evaluation should be observed in all phases and be conducted in a participatory manner in order to ensure that the steps are responsive to the needs of the community and promote the value of their cultural heritage.

Employing a holistic community organizing strategy for IPs will facilitate the development of a community-based system that utilizes maximum participation and cultural empowerment at the same time sustaining cultural integrity. The study suggests the best and effective practices and tools that can be used in order to have meaningful participation towards IPs. Needless to say, interventions should be tailored and best developed on a community level basis by stakeholders and community organizers to ensure all factors will be considered.

In order to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed community organizing protocol, testing the framework on indigenous communities in the Philippines is recommended. The proposed approach is not being suggested as a cure-all formula nor as a replacement of the existing community organizing process, however it is recommended to apply it on existing programs of the government or NGOs in order to assess its effectiveness.

Due to the complexity of community organizing in indigenous communities, this should be verified on a community-level basis by the IP organizers and researchers working closely with the community. Needs analysis and primary data gathering is highly recommended to know the strength and weaknesses of each tool since the findings on the general population do not always accurately reflect indigenous communities due to their distinct social patterns.

The proposed protocol should be undertaken in close coordination with the National Commission on Indigenous People at the national and local levels, while at the same time ensuring that the four bundles of rights defined by IPRA are met (Right to Ancestral Domains and Lands, Right to Self-Governance and Empowerment, Right to Social Justice and Human Rights, and Right to Cultural Integrity).

Citation: Bamba J, Candelario C, Gabuya R, Manongdo L (2021) Community Organizing for Indigenous People in the Philippines: A Proposed Approach. J Ergonomics. S5:002.

Received: 15-Sep-2021 Accepted: 29-Sep-2021 Published: 06-Oct-2021 , DOI: 10.35248/2165-7556.21.s5.002

Copyright: © 2021 Bamba J, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.