Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence

Open Access

ISSN: 2329-6488

ISSN: 2329-6488

Research Article - (2015) Volume 3, Issue 4

Background: The alcoholic psychoses incidence rate is a reliable indicator of alcohol-related problems at the population level since there is a strong relationship between alcoholic psychoses incidence rate and alcohol consumption per capita. Aims: To estimate the aggregate level effect of alcohol on the psychoses incidence rate in the former Soviet Republics Russia and Belarus. Method: Trends in alcoholic psychoses incidence rate and alcohol sales per capita from 1970 to 2013 in Russia and Belarus were analyzed employing an ARIMA analysis. Results: Alcohol sales is a statistically significant associated with alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in both countries, implying that a 1-l increase in per capita alcohol sales is associated with an increase in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate of 18.6% in Russia and of 18.8% in Belarus. Conclusion: This is the first comparative time-series analysis of alcohol sales and alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus, which highlighted close temporal association between alcoholic psychoses rate and population drinking in both countries.

Keywords: Alcoholic psychoses, ARIMA time series analysis, Russia, Belarus, 1970-2013

Alcohol is a major contributor to premature deaths toll in Eastern Europe [1]. Its effects on mortality seem to have been especially striking in the Slavic countries of the former Soviet Union (fSU), where it has been identified as one of the most important factor underpinning the mortality crisis that has occurred in the post-Soviet period [2]. Despite some positive changes in recent years, the former Soviet republics Russia and Belarus ranks among the world’s heaviest drinking countries with an annual official consumption rate about 10 litres of pure alcohol per capita [3,4]. Furthermore, according to the WHO, in 2010, Belarus appears at the top of global rating with 17.5 litres of total alcohol consumption (including unrecorded consumption) per capita [5]. Evidence of a major effect of binge drinking on mortality pattern in these countries comes from both aggregate level analyses and studies of individuals. In Russia, for example, alcohol may be responsible for 59.0% of all male and 33.0% of all female deaths at ages 15-54 years [6]. Corresponding figures for Belarus are somewhat lover: 28.4% of all male and 16.4% of all female deaths [7]. The drinking culture in Russia and Belarus is rather similar and characterized by a high overall level of alcohol consumption and the heavy episodic (binge) drinking pattern of strong spirits, leading to a high alcohol-related mortality rate [8,9].

In comparative perspective, Belarus presents an interesting contrast to other former Soviet countries with extremely high alcohol-related mortality rate. The developmental path in Belarus has been somewhat different to that seen in other countries in the post-Soviet period. The country never fully democratized and there has been less emphasis on economic reform, with many aspects of the command economy being retained, as witnessed by the low level of privatization [10]. By contrast to Russia, which implemented mass privatization after the collapse of the former Soviet Union, Belarus has adopted a more gradual approach to transition? In relation to this, [11] argue that rapid mass privatization and increased unemployment rate in the early 1990s was the major determinant of the mortality crisis in Russia during this time.

Alcoholic psychosis is a secondary psychosis that usually occurs in alcohol-dependent individuals after the prolonged period of heavy drinking and withdrawal [12]. The alcoholic psychoses incidence rate is a reliable indicator of alcohol-related problems at the population level since there is a strong relationship between alcoholic psychoses incidence rate and alcohol consumption per capita [13-15]. Although alcoholic psychoses rate was comparatively high in Russia and Belarus, even during the later-Soviet period, the alarming rise that has occurred during the post-Soviet period means that these countries have one of the highest alcoholic psychoses rate in the world (WHO, 2014).

This study examines the phenomenon of alcoholic psychoses in Russia and Belarus from the late Soviet to post-Soviet period. It goes beyond previous studies that have been confined primarily to Russia and focused on alcohol-related mortality with few examples from elsewhere even though other former Soviet republics have experienced similar fluctuations in alcohol-related morbidity and mortality rates. More specifically, this study focuses on a comparative analysis of trends in alcoholic psychoses incidence and alcohol sales per capita in Russia and Belarus.

Data

We specified the number of persons, witches were admitted to hospital for the first time as incidence of alcoholic psychoses: (ICD–10: F 10). Since alcoholic psychosis is a disease in which patients are usually admitted to hospital, first admission figures are good proxy of the real incidence. The data on alcohol psychoses incidence rate (per 100.000 of the population) and data on per capita alcohol sales (in liters of pure alcohol) are taken from the Russian State Statistical Committee (Rosstat) reports and Belarussian State Statistical Committee (Belsstat).

Statistical analysis

To examine the relation between changes in alcohol sales and alcohol psychoses incidence rate across the study period a time-series analysis was performed using the statistical package “Statistica”. The dependent variable was the alcohol psychoses incidence rate and the independent variable was aggregate alcohol sales. Bivariate correlations between the raw data from two time-series can often be spurious due to common sources in the trends and due to autocorrelation [16]. One way to reduce the risk of obtaining a spurious relation between two variables that have common trends is to remove these trends by means of a ‘differencing’ procedure, as expressed in formula:

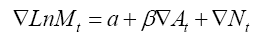

This means that the annual changes ‘’ in variable ‘X’ are analyzed rather than raw data. The process whereby systematic variation within a time series is eliminated before the examination of potential causal relationships is referred to as ‘prewhitening’. This is subsequently followed an inspection of the cross-correlation function in order to estimate the association between the two prewhitened time series. It was [17] who first proposed this particular method for undertaking a time series analysis and it is commonly referred to as ARIMA modeling. We used this model specification to estimate the relationship between the time series alcohol psychoses incidence and alcohol sales in this paper. In line with previous aggregate studies [16] we estimated semilogarithmic models with logged output. A semi-logarithmic model is based on the assumption that the risk of alcohol-related problems increases more than proportionally for a given increase in alcohol consumption [16]. The following model was estimated:

where ∇ means that the series is differenced, M is alcoholic psychoses incidence rate, a indicates the possible trend in alcoholic psychoses incidence rate due to other factors than those included in the model, A is the alcohol sales, β is the estimated regression parameter, and N is the noise term. The percentage increase in alcoholic psychoses incidence rate associated with a 1-litre increase in alcohol sales is given by the expression: (exp(β1)-1)*100.

The average alcoholic psychoses incidence figure for Russia and Belarus was 27.7 and 17.3 per 100.000 respectively. The trend in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate is displayed in Figure 1. As can be seen, two countries have experienced similar fluctuations in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate over the Soviet period. This index increased steadily from 1970 to 1980, decreased markedly from 1980 to 1984, dropped sharply between 1984 and 1988, than started an upward trend from 1998 to 1992. While the trends in alcoholic psychoses incidence have been similar in both countries during the Soviet period, there was significant discrepancy after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Trend in alcoholic psychoses incidence have fluctuated greatly in Russia: jumped dramatically during 1992 to 1995; from 1995 to 1999 there was a fall in the rates before they again jumped between 1999 and 2003, and then started to decrease in the most recent years. In Belarus, alcoholic psychoses incidence increased steadily up to 1999 and then started to decrease. The comparative analysis of long-term evolution of alcoholic psychoses rate suggests that in the 1970s the rate was considerably lower in Belarus than in Russia. This gap practically disappeared during the Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign: between 1984 and 1988 alcoholic psychoses rate decreased 4 times in Russia (from 20.5 to 5.1 per 100.000) and 3.9 times in Belarus (from 15.6 to 4.0 per 100.000). After the collapse of the fSU, the alcoholic psychoses rate was growing steadily in Belarus, whereas in Russia there was a sharp grows in the first half of 1990s followed by a decline, which resulted in comparatively high alcoholic psychoses rate in Belarus by the end of 1990s.

The average per capita alcohol sales figure for Russia and Belarus was 8.4 and 8.8 litres per capita respectively. The temporal pattern of alcohol sales per capita in Russia and Belarus was similar across the Soviet period (Figure 2). As can be seen, the alcohol sales decreased slightly in the early 1980s, and then decreased dramatically between 1984 and 1987. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, recorded alcohol consumption in Russia rose sharply between 1992 and 1995, decreased substantially in 1996, increased steadily up to 2007, and then started to decrease. In the post-Soviet Belarus alcohol sales increased steadily with several oscillations up to 2005, than jumped dramatically, and since 2011 started to decrease.

The graphical evidence suggests that in Russia, the temporal pattern of alcoholic psychoses incidence rate fits closely with changes in alcohol sales per capita (Figures 3,4). By contrast, there was significant discrepancy between these trends in the post-Soviet Belarus: decrease in alcoholic psychoses incidence rate against upward trend in alcohol sales per capita between 1999 and 2011. There were sharp trends in the time series data across the study period. These trends were removed by means of a first-order differencing procedure. The specification of the bivariate ARIMA model and outcome of the analyses are presented in (Table 1). According to the results, alcohol sales is a statistically significant associated with alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in both countries, implying that a 1-l increase in per capita alcohol sales is associated with an increase in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate of 18.6% in Russia and of 18.8% in Belarus.

| Parameter | Model | Estim. | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russia | 0.1.0* | 0.186 | 0.000 |

| Belarus | 0.1.0 | 0.188 | 0.000 |

Table 1: Estimated effects (bivariate ARIMA model) of alcohol sales on alcoholic psychoses rate.

According to the results of present analysis there was a positive and statistically significant effect of per capita alcohol sales on alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus and the magnitude of this effect was similar in both countries. These results are consistent with the previous findings that highlighted close temporal association between alcoholic psychoses rate and population drinking [13-15].

Elucidating the phenomenon of high alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus, however, does little to understand the reasons for it dramatic fluctuations across time. As it was mentioned above, rapid mass privatization and increased unemployment rate was suggested as the major determinant of the mortality crisis in Russia in the early 1990s [11]. Several studies have shown that unemployment have adverse effects on physical and mental health [18]. It was also assumed that this association is mediated through psychosocial distress, which leads to the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle including smoking and hazardous drinking [19]. Nevertheless, there are some inconsistencies in the findings concerning the association between unemployment and alcohol-related outcomes. In particular, findings from the former Soviet Republic Lithuania have failed to show any association between unemployment and alcoholic psychoses rate [20]. In relation to this, it should be emphasized that the pattern of alcoholic psychoses rate in both countries resemble of those total mortality rate. Furthermore, in an analysis of the determinants of mortality in post- Soviet countries Earle and [21] find no evidence that privatization increased mortality during the early 1990s. This evidence suggests that rapid mass privatization, increase unemployment and psychosocial distress do not provide a sufficient explanation for cross-country differences in alcohol-related morbidity and mortality trends during the transition to the post-communism. It seems plausible that alcoholdependent individuals do not particularly sensitive to psychosocial distress caused by the rapid social transformation but, instead, sensitive to availability and affordability of alcohol. Russian historical perspective provides sufficient evidence for this [22,23].

One of the most intriguing phenomenon in this context is the substantial decline in alcohol consumption and alcoholic psychoses rates that occurred between 1980 and 1984, which might be attributed to the increase in the price of vodka in 1981 [24]. Furthermore, the new Soviet leader Andropov, who came to power in 1982, realized that mass drunkenness was a major threat to the Soviet system and saw a great opportunity to increase labor productivity by sobering up the nation. He took a number of steps in this direction using police methods to strengthen labor discipline and to fight against drunkenness in the workplace [24]. It might be the case that this policy resulted in a decline in both per capita alcohol consumption and the alcohol-related mortality level.

An especially sharp fall was recorded in alcohol sales in 1985–1987 that coincided with Mikhail Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign, which substantially reduced availability and affordability of alcohol. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the ending of the state’s alcohol monopoly in January 1992 were accompanied by a sharp rise in alcohol sales. [22] argue that the increase in alcohol consumption in the early 1990s, which explains much of the rise in mortality, resulted largely from an increase in the affordability of vodka. With price liberalization in 1992, vodka became much more affordable because of a dramatic drop in its relative price. In the period from 1995 the real vodka price recovered somewhat until 1998, after which point the trend turned down again [3]. After 1998, alcoholic psychoses rate increased as well.

Some researchers attributed the Russian mortality crisis between 1992 and 1994 to the group of heavy drinkers, whose lives were saved during the anti-alcohol campaign [3]. It was also suggested that mortality in this group explains the subsequent fluctuations in alcoholrelated mortality. However, the substantial discrepancies between the trends in alcoholic psychoses rate in Russia and Belarus during the recent decades do not support this hypothesis.

Since 2003, Russia has experienced steep decline in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate which might be attributed to the implementation of the alcohol policy reforms in 2001–2006, which increased government control over the alcohol market [25,26]. The policies included strict regulations on alcohol products, which resulted in a decline in a distributors and increased consumer prices [25,27]. This empirical evidence suggest that recent Russian government’s attempt to curb the high alcohol-related morbidity and mortality have been at least partially successful and provide additional evidence that pricing policy may be an effective strategy to reduce an alcohol-related burden. There is, however, some doubts that recent decline in alcoholic psychoses rate in Russia is fully attributable to the alcohol control measures, since downward trend in alcoholic psychoses rate started before decline in recorded alcohol consumption.

In Belarus, alcoholic psychoses rate started to decrease since 1999, despite upward trend in recorded alcohol consumption. This apparent paradox can be explained by the recent alcohol control policies implemented in this country. It seems plausible that grows in recorded alcohol consumption took place in compensation for the sharp fall in unrecorded consumption, which started since 1997. This trend coincides with an increase in state control over the alcohol market, including an intensification of the fight against home distillation, as well against consumption of surrogate alcohol [10]. A reciprocal relationship between unrecorded alcohol consumption and official alcohol sales can explain the paradox of how the alcoholic psychoses rate decreased at the same time that alcohol sales increased substantially.

Before concluding, we should address the potential limitations of this study. In particular, we relied on official alcohol sales data as a proxy measure for trends in alcohol consumption across the period. However, unrecorded consumption of alcohol was commonplace in Russia throughout the study period, especially in the mid-1990s, when a considerable proportion of vodka came from illicit sources [3,28]. The consumption of homemade spirits (samogon) and surrogates might also have a particularly negative impact on alcohol-related morbidity and morbidity [29].

Further, the limitations stem from effects, which might interfere with time series of alcoholic psychoses incidence data: change of classification systems and diagnostic habits, changes in health service organization (use of new forms of alcoholism treatment/rehabilitation, early intervention programs, and alternative services). It is possible that the increase in alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus in the mid-1990s, at least partly, was a consequence of deterioration in the quality of health care system, following the collapse of Soviet Union in late 1991. As the command economy collapsed, the public health system faced a financial crisis. Left without proper funding, the health care system was unable to maintain the needed level of medical care [19]. A process of destruction of the state-funded narcological service that began in 1989 continued in the 1990s [3]. During the 1990s, three main changes, all linked to broader post-Soviet political and economic transformations, had significant effects on the narcological service: the arrival of new forms of alcoholism treatment and rehabilitation, the commercialization of narcology and the abolishing of compulsory treatment [30]. However, while many aspects of alcoholism treatment in post-Soviet Russia had been radically transformed during the 1990s, the overall structure of the state-funded network had not changed significantly since the 1970s when the Soviet narcological service was established [31].

In conclusion, this is the first comparative time-series analysis of alcohol sales and alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus, which highlighted close temporal association between alcoholic psychoses rate and population drinking in both countries. The outcomes of this study provide indirect support for the hypothesis that the dramatic fluctuations in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rate in Russia and Belarus during the last decades were related to the availability/affordability of alcohol [32,33]. The findings from the present study have important implications as regards alcohol policy, suggesting that any attempts to reduce alcohol-related burden should be linked with efforts through restriction of availability/affordability of alcohol.

None declared