Indexed In

- CiteFactor

- RefSeek

- Directory of Research Journal Indexing (DRJI)

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Scholarsteer

- Publons

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 6

Psychological Determinants of the Success of the Entrepreneurial Support Relationship

Fitouri Mohamed1* and Samia Karoui Zouaoui22Department of Management, University of Tunis El- Manar (FSEG Tunis), Tunisia

Received: 17-Mar-2021 Published: 08-Jul-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2315-7844.21.9.291

Abstract

The existence of support structures have for reasons for improving the performance of newly created companies. However, many companies, despite their support, go bankrupt. Taking an interest in the issue of the performance of newly created companies from the perspective of support is very central. In this research work, we addressed the question of the influence of the entrepreneur's commitment on the success of the entrepreneur-coach relationship. Our empirical field is made up of novice Tunisian entrepreneurs. We followed a quantitative methodology by collecting data from “350 novice entrepreneurs. The results show that the success of the entrepreneur-coach relationship is conditioned by the entrepreneur's commitment.

Keywords

Psychological determinants; Entrepreneurs; Coaching Relationship; Implement; Performance

Introduction

The current rates of post-creation failure of newly created businesses suggest that it would now be appropriate to initiate studies on the determinants of success of the coaching relationship; capable of revealing possibly poorly met coaching needs. All the more so since studies show that creation projects that have received support have higher short and medium-term survival rates [1-5].

Therefore, in order for the entrepreneur and his or her coach to ensure the performance of the newly created enterprise, they must co-construct their coaching relationship through their exchanges, and implement and evaluate the actions necessary to achieve this objective [6]. In fact, according to the latter, to be effective, the coaching relationship must be co-constructed by both parties: the entrepreneur and the coach. It follows that each party finds "its place" and its interest in the coaching relationship.

The coaching relationship must be a real key to the performance of the company being created and to the personal development of the entrepreneur, and the latter must develop reflexes aimed at perpetuating the good practices encouraged by his coach. However, despite the fact that entrepreneurship researchers consider that effective coaching has an effect on the success of the entrepreneur and the performance of his or her business and that the coaching relationship has a role in achieving the results or benefits of coaching. In this context, asking questions about the factors that determine the success of this relationship is of major importance. Indeed, since the contribution of Bruyat [7] about the importance of the relational dimension in coaching, the work done in this field is embryonic.

The few research studies carried out on this subject show that the accompanying person and the person being accompanied must have a certain number of characteristics for the accompanying relationship to succeed. In this regard, considers that if the behaviour of the coach is ideal to be able to succeed in the coaching relationship, then the openness, commitment of the entrepreneur and trust towards his coach are necessary. The entrepreneur must be receptive to the coach's advice, must be committed to the relationship and open to change. Engstrom argues that the entrepreneur must have a willingness to receive advice from an outsider, some desire for change, and be open to having new experiences. Although there are many theoretical developments that presume the existence of positive links between the entrepreneur's trusts in the coach, the existence of the psychological contract and the entrepreneur's commitment with coaching relationship success, but empirical studies on this subject are rare. Therefore, we asked ourselves the following question: Do these psychological determinants have an influence on the entrepreneurial coaching relationship? [8-10].

Definitions of Research Variables

The entrepreneurial support relationship

There are many definitions of entrepreneurial support in the scientific literature. However, the different forms that support can take as well as the many cognitive interactions between support and support. Make the exercise of the single definition more complex. Define support as follows: “Support is presented as a practice of helping the creation of a business, based on a relationship that is established over time and is not one-off, between an entrepreneur and an individual external to the creation project. Through this relationship, the entrepreneur will achieve multiple learning and be able to access resources or develop skills useful for the realization of his project. [11-13].

Nevertheless insists on the role of moral and psychological support that falls to the accompanist, especially in periods of doubt of the accompanied. Hence, as argues, it is necessary to take into account the mutualist relationship between accompanied and accompanying. Mentions that there are gaps in the literature concerning the modelling “of what is played between the two interlocutors in the support relationship”. In this context, Rice used the term "co-production" to illustrate the way in which entrepreneurial support relationships work. Both the accompanying person and the accompanying person must therefore have a certain number of characteristics so that the accompaniment relationship can be beneficial for both parties. Thus, according to the support person must show a certain degree of empathy must be attentive to the support person, must be at ease within the environment. In which the accompanied evolves and must appear credible in the eyes of the accompanied. The accompanying person must be receptive to the advice of the accompanying person, must be committed to the relationship and open to changes. In addition, insisted on the importance of the bases on agreeing the two parts as for the progress of the accompaniment. Indeed, it is important that is established a kind of moral contract specifying the targeted objectives, the means that will be put in place to achieve them, the respected roles of the coach and his protégé and an action plan including a timeline [14-17].

Trust as a success factor in the coaching relationship

Given the lack of work on trust and the entrepreneurial support relationship, we have borrowed from the work done on trust in the management field. In this regard, the literature informs that the definitions dedicated to trust can be grouped under two approaches [18]. The first approach is based on the cognitive and affective aspect of expectation, while the second is based on the behavioural intention [19].

According to the psychological approach, trust would exist only through a cognitive component belief, expectation, goodwill, hopes. Justify the choice of the psychological approach in the conceptualization of trust by the posteriority of intentions to expectations. Thus, the behavioural intention that corresponds to a presumption or to a commitment is an outcome of trust [20,21].

According to the behavioral approach, trust is analysed as a risktaking behavior in the exchange. According to this view, trust is understood as a behavioral intention that translates into a willingness to be vulnerable and to take risks. In an attempt to reconcile the two approaches, some researchers view trust as a twosided concept that incorporates expectations and behavior at the same time. Other researchers are highly critical of the separation between the psychological and behavioural domains of trust. They argue that behavioural intention is implicit in its definition. According to we have a predominance of the cognitive approach in the definition of trust. It is important to argue that despite its major role in any social and relational exchange, trust remains a difficult concept to define. Moreover, it is not easy to apply it in an identical way to all research fields, particularly to entrepreneurial support. However, this analysis has enabled us to arrive at a definition of this concept: trust is the set of beliefs and expectations that lead the entrepreneur to consider that the coach will act in the interest of their coaching relationship. It therefore implies faith, the belief that the entrepreneur is willing to maintain an action in the desired direction [22].

Based on a review of the literature on trust, we divide trust in the context of entrepreneurial support into two categories: the trust of the entrepreneur s trust in the coach (interpersonal trust) and his trust in the host organization (incubator, business center, etc.) (Inter-organizational trust). "(Inter-organizational trust).

Although for some researchers, the two notions are closely linked, an ambiguity remains in this respect. Indeed, the authors have noted that there is a difference in nature between trusting an individual (coach) and trusting an organization (coaching structure). Indeed, according to trust is above all a question of relationship between individuals. In our case, it is the trust between the entrepreneur and the coach. It is not possible to talk about trust at the level of a coaching organization since we can only trust its members and the relationships that are established between them. This is called interpersonal trust. Hence, the interpersonal basis appears to be the legitimate anchor of trust. For many, interpersonal trust is built essentially on cognitive and affective components [23-27].

The cognitive component is built on relatively objective characteristics that the entrepreneur attributes to the coach, such as competence, integrity, and honesty, based on the coach's previous experiences. As for the affective component of trust, it corresponds to a very emotional attachment relationship, which makes it more difficult to build. It requires very frequent interactions between the two parties of the dyad (the entrepreneur and the coach). Affective trust is thus associated with an investment in terms of time and feelings [28].

As for inter-organizational trust, it goes beyond the interpersonal relationship between the entrepreneur and the coach, and encompasses the entire coaching organization. Indeed, it is clear that it is always people who trust each other, not organizations, and that exchanges between organizations are exchanges between individuals or small groups of individuals. However, coaching organizations have a reputation and an image. They develop procedures, norms, values and principles with the aim of unifying the behavior of their coaches with respect to their external interlocutors, which are only novice entrepreneurs. For the two paths of trust influence each other. Thus, interpersonal trust can be the source of organizational trust, and vice versa. Many authors argue that organizational trust can only exist at the interpersonal level. Other authors consider that, although interpersonal trust and inter-organizational trust are very similar, they have neither the same antecedents nor the same consequences. The antecedents of inter-organizational trust lie primarily in the characteristics of the coaching organization, whereas interpersonal trust is concerned with the personality of the coach and the nature of the relationship with the coachee [29-31].

Similarly, the literature indicates that trust can take three main forms [32]. The first form, described as contractual, concerns the respect of promises (written or oral). It resides in the entrepreneur's belief that his or her coach respects universal ethical standards, such as keeping his or her word or maintaining confidentiality. This type of trust comes more from formal mechanisms (contracts) than from past exchanges or personal elements.

The second type of trust is technical trust, which is based on knowledge. It is linked to the entrepreneur's expectation that his or her coach will carry out the task with professionalism, which implies the technical and managerial capacities of the coach. This type of trust originates in the predictability and credibility of the coach. It is based, on the one hand, on the entrepreneur's sufficient knowledge of the coach that allows him to anticipate his behaviour, and, on the other hand, on credible information about the coach's intentions or skills. This is interpersonal trust of a cognitive nature, referred to as "cognitive trust" by Garbarino, Johnson and Lewis J et al. [33,34].

The last form of trust is called relational and is linked to the reliability and seriousness demonstrated during the entrepreneur's interactions with his coach, which generate positive expectations about the coach's intentions. It develops over the course of the experience, establishes a certain overall climate and takes into account reciprocity between the two parties: the trust that is granted and the trust that is perceived. This type of trust is therefore based on the integrity of the exchange dyad. It arises from the fact that the parties are committed and respond in an open manner Usunier. Relational trust can be motivated by a strong positive feeling towards the other party. Barney and Hanson refer to it as "strong trust and Ring refers to it as "resilient trust." Studies show that technical trust is necessary at the beginning of the relationship; as the relationship evolves, it moves beyond this stage. The more the dyad is involved in the exchange, the more the trust induces a long-term orientation and the trust then appears as relational. Contractually based trust qualified as the most "fragile" form of trust ring [35-37].

Regarding the operational construct of trust, the literature does not establish any consensus. Some authors consider it as a unidimensional construct [38]. Others consider it as a multidimensional variable, but seem to disagree on the number of dimensions to be retained: two for Guviez in 1999, three for Mayer et al. in 1995, Gurviez and Korchia in 2002 and Akrout in 2011 or even eleven according to Butler. In any case, based on the definitions of trust presented earlier, a number of dimensions related to this concept emerge, such as competence, honesty, credibility, integrity, benevolence and goodwill.

Competence: this is the set of skills necessary to perform a task properly and effectively in a given situation Mayer et al. It refers to the skill, know-how and expertise of the coach, i.e., his or her aptitude in terms of professionalism. Research has shown that the "competence" dimension underpins trust in the coach and determines the relationship between coach and entrepreneur. According to Josée Audet et al. the entrepreneur must recognize the expertise of his coach and consider that this expertise is necessary in order to facilitate the resolution of the problems of the business being created. Indeed, the coach must be able to lead the entrepreneur to be open to change, to eventually acquire new knowledge or skills and modify his or her behaviors accordingly [39,40].

Honesty: this is the belief that a partner will keep his or her promises and be sincere and reliable. According to Audet et al., not only can the absence of promises be detrimental to the quality of the coaching relationship, but its non-fulfillment can also have harmful consequences.

Credibility: The coach must gain the trust of the person being coached so that the latter agrees to open up to him. To achieve this, the coach must first establish credibility with the entrepreneur [41,42].

Integrity: This is the belief that the coach keeps his or her promises and adheres to established rules for conducting exchanges [43]. According to Morgan and Hunt, a partner with integrity must be "competent, honest, sociable, and responsible.

Benevolence: This dimension corresponds to the good intentions of the coach and his or her perceived determination to pay attention to the needs and well-being of the entrepreneur.

At the end of this development, we conclude that the coaching relationship must be based on trust and confidentiality in order to promote authentic and effective exchanges. Indeed, several authors note that trust is a key component of the quality and effectiveness of the coaching relationship Barrett and that it must be mutual so that the functions of the coach can be deployed to the maximum In the context of entrepreneurial mentoring, the relationship between trust and the mentor's functions was empirically tested by St-Jean and his results showed that the entrepreneur's trust in the mentor positively influences the deployment of functions. These functions also promote the development of the entrepreneur's learning. Indeed, if the entrepreneur has confidence in his or her coach, the latter will commit to providing the necessary support through the functions he or she performs. Insofar as the objective of coaching is to support the entrepreneur by transmitting his or her knowledge and skills, trust in the relationship is essential for the transmission of knowledge. In this context, admit that establishing a relationship of trust with the entrepreneur is essential for the coach to be able to intervene at the level of intimate learning mechanisms [44-48]. Hence we find it legitimate to deduce and formulate our first hypothesis as follows:

H1: The trust of the entrepreneur towards his coach has a positive influence on the entrepreneurial coaching relationship.

Commitment as a success factor in the coaching relationship

It should be pointed out that the work done to date on the entrepreneur-coach relationship or even in the field of the organizational or business coaching relationship does not present the commitment in any detail. There are two main reasons for this: The first reason is the fact that the concept of commitment is still embryonic in the entrepreneurship literature despite the fact that it has been used for a long time by Bruyat.

The second reason is related to the complexity and diversity of the field of antecedents of commitment in management science. However, we believe that following the example [49]. We can better understand the dynamics of commitment can allow for better support for newly created companies. Indeed, improving the knowledge that one can have of commitment can allow for a more judicious allocation of support resources, by reserving them for entrepreneurs for whom the conditions relating to an acquired or latent commitment are met.

Therefore, a presentation of the term "commitment" seems to be a crucial task. Furthermore, the clarification of the notion of "commitment" also comes back to the dissonance detected by scanning the managerial literature. It puts two different translations osf the Anglo-Saxon term "commitment": Engagement and Implication. Indeed, most researchers in France translate "involvement" as "engagement" and "commitment" as "implication".

Similarly, the Quebec literature uses the term "engagement" to designate the notion of "commitment". Indeed, such misunderstandings could in no way systematize the research and consequently create a theoretical framework in the true sense of the term, since there is a controversy as to which term is equivalent to the Anglo-Saxon term.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that the academic literature on the notion of commitment is characterized by a disproportion between, on the one hand, a certain abundance of empirical studies that have sought to identify its determinants or consequences and, on the other hand, a rather small number of theoretical and/or conceptual contributions that have sought to specify the nature of commitment in a more profound manner.

The second observation to be made when examining the synthetic studies carried out by some authors in human resources management is the lack of consensus on the definition of the construct, which is all the more striking when using measures that often do not correspond to the conceptual definition. Nevertheless, we believe that it is useful to present the distinction between the two perspectives of commitment, namely the attitudinal and the behavioral, before proceeding with the inventory of definitions of the term "commitment". Indeed, this distinction is well established by the authors Attitudinal commitment, in our case, represents the individual identification (of the entrepreneur) with a target (the company) and the willingness to work for its benefit, whereas the behavioral perspective focuses on an approach by the attributes of commitment, and which results from the connection of the entrepreneur to his behavioral acts [50,51].

Based on a review of the entrepreneurship literature, we can say that, the different definitions of "commitment" could be categorized according to three general themes: an affective attachment to the target, the perceived costs associated with leaving and the obligation to maintain membership [52,53].

In this context published an article on the effects of affective, Calculated, and normative commitment on the intention to stay in the entrepreneurial profession. His results confirm that all three dimensions of the job commitment model apply well to entrepreneurs. Furthermore Alexis et al. [54], considers that in order to avoid forms of "escalation in support", which are possible sources of disappointment, the commitment of the parties is essential. Similarly, committed stakeholders base the support relationship on an interpersonal dimension.

Concerning the measurement of commitment, most authors use the measurement scale of operationalizes this concept.

A coaching relationship requires a time investment on the part of the dyad. Most programs span years and require meetings between the entrepreneur and his or her coach. In addition to physical availability for meetings, the coach must be intellectually available to focus on the protégé's problems during and outside of meetings. Cull emphasizes a strong demand for support, presence and availability on the part of the mentee. The commitment must be mutual for the relationship to be successful; the entrepreneur must voluntarily engage in the relationship and be receptive to coaching. The coach must also voluntarily commit to the relationship in order to maintain a sufficient level of motivation and availability. The generosity and availability of the mentor and the fact of being able to count on the reassuring presence of the mentor at all times cite the presence of an experienced person as a factor of satisfaction for entrepreneurs [55-57].

The concept of commitment has been the subject of numerous studies since the 1960s. Today, it is considered a key variable in the coaching relationship [58]. Consider it as "the variable that distinguishes transactional from relational exchanges". Engagement has become for some researchers the essential ingredient for a successful relationship. Despite this interest in the concept, to our knowledge, there is no consensus today on a characterization and on the use of a measurement tool.

In the field of business coaching, commitment can be defined as the intention of an entrepreneur to continue the relationship with a coach in the sense of Indeed; two reasons can be at the origin of this intention. It can be linked either to a psychological attachment or to an economic constraint. Consequently, two approaches to commitment can be distinguished. A first approach where researchers have seen in the commitment a psychological constraint that locks the two parties of the dyad in the entrepreneurial support relationship. In this case, the commitment is no longer granted to a promise of relational continuity, but rather translates into investments in time and resources, impossible to redeploy in another relationship. In this first approach, called imposed relationship, the commitment is thus the consequence of economic barriers that arise within the framework of a relationship and whose calculated dimension constitutes the reflection of this approach. The second approach, called the preferred relationship, considers the commitment to be voluntary and intentional, based on the attraction that the relationship has for the entrepreneur [59,60]. It creates a kind of attachment between the entrepreneur and the coach and aims to guarantee the stability of the coaching relationship. The two dimensions of affective and normative commitment reflect this orientation of commitment.

In fact, considering the entrepreneur's commitment as a determining factor in the success of the coaching relationship can be justified by the definitions that have been proposed in the literature for this concept. First, some authors emphasize the desire to maintain a long-term relationship in their definitions of commitment. Commitment to a relationship implies a desire to continue it with a willingness to make the maximum effort to maintain it. Commitment to a relationship is therefore only meaningful over the long term. Indeed, this relationship must be long term and, above all, it must remain consistent over time [61]. In this context, authors in entrepreneurship who study the coaching relationship emphasize the duration of the relationship and insist that the relationship must be anchored in time.

Second other researchers emphasize the willingness to invest in the relationship in their definitions. Commitment can be revealed through the investments made by the dyad in the coaching relationship. According to Wilson and Vlosky these investments are non-transferable and cannot be recovered outside of the coaching relationship. The willingness to invest in the relationship demonstrates the trustworthiness of both parties; the greater the investment, the lower the risk of opportunism [62].

Finally, researchers have defined commitment as a psychological bond. Indeed, to engage in a relationship reflects a certain attachment, an involvement or identification with the partner. The attachment translates an affective relation towards the companion and expresses a relation of psychological proximity with this one It is defined as a psychological, emotional, strong and lasting relationship. A long-term affective relationship depends on the strength of the emotional bond between the two parties. Regarding the dimensions of commitment in entrepreneurship, the work of proposed a multidimensional approach to the concept of commitment facilitating its understanding and thus its definition. The dimensions used in this approach are the affective, calculated and normative dimensions. These dimensions refer to distinct components and each indicates a particular state of mind and motivation linked to the nature of the relationship between the entrepreneur and his or her coach [63-65].

Affective commitment has been described in terms of "attitudinal" commitment, "psychological attachment", "identification", "affiliation", "value congruence", "involvement" and "loyalty". Calculated commitment is an entrepreneur's perception of maintaining the relationship because of the significant transfer costs of breaking it off. It is often considered a "calculating" act and thus labelled as "calculated" because it involves a complete information processing process. This commitment is the result of a subjective estimation of the costs, risks and benefits associated with a change in the coach. Normative commitment is based on a sense of moral obligation [66,67].

At the end of this development, we conclude that the coaching relationship must be based on the entrepreneur's commitment, from which we formulate our second hypothesis as follows:

H°2: The entrepreneur's commitment positively influences the entrepreneur-coach relationship.

The existence of a psychological contract as a success factor in the coaching relationship.

The psychological contract is defined as a concept that makes it possible to study an exchange, it links two parties: the entrepreneur and the attendant [68,69]. Which Aims to understand and analyse the dynamics of this relationship, and how the exchange develops and evolves over time?

Two ideas are therefore inherent in the concept of psychological contract: mutuality and reciprocity. This means that both parties are involved in the psychological contract, the contractor and the attendant. They are both involved in this contract, which is a condition for a mutuality to exist. Therefore, both parties should be asked about the performance of the psychological contract. The psychological contract can be understood as a process of adjustment over time, which is explained by the way each party responds to the degree of fulfilment of the other party's promises.

Reciprocity in the entrepreneurial-accompanying exchange relationship implied "that each of the two parties should be asked about the fulfilment of promises by the other party, but also by oneself. Measuring mutuality and reciprocity in detail requires a clear identification of the attendant and the contractor, as well as what each thinks of the promises made for the other party. Some authors in psychology have circumvented this difficulty by limiting the scope of the psychological contract to the single prism of a single actor. According to this contract exists and evolves in the eyes of the individual. Mutuality is then measured only by taking into account the perceptions of one of the actors on the promises of both parties. According to psychological contract is only one of several concepts in the theory of social exchange, the specificity and strength of psychological contract consists in studying exchange through mutual promises and obligations. It is precisely because one is interested in promises that one thinks one can analyse the accompanying relationship as it is conceived and discussed at present. What kind of promises can be found in a psychological contract in an accompanying context? As the psychological contract is individual and specific to each relationship, it is difficult to establish a list of obligations that would be universally encountered. Worked on the so-called "relational" elements of the psychological contract, that is, oriented towards a lasting, affective exchange, and cantered on loyalty and career within the same company [70-72].

Studying and measuring the psychological contract is not just about analysing the promises made by the attendant and the entrepreneur, but it is necessary to these promises are fulfilled. The performance of the psychological contract is covered by three indicators:

• Breakage (in English, breach or underfulfde),

• Compliance (fulfilment)

• Overstepping of promises (overfulfde).

The study of the realization of the psychological contract through the mere breaking of promises offers only a very piecemeal view of the phenomenon, which focuses on breaches of promises and shortcomings. However, an attendant can, on the other hand, exceed his promises and offer the entrepreneur more than he has promised. This possibility is rare, because entrepreneurs frequently perceive breaks in the psychological contract, but much less a breach of promises. The question arises, however, especially for those who work hard to retain their entrepreneurs, especially for projects with a high success rate. Three indicators of the degree of performance of the psychological contract can therefore be envisaged:

• Respect for promises (cognitive assessment, achievement of what has been agreed);

• Under-fulfillment or breakdown of promises (cognitive assessment, non-fulfillment of what has been agreed);

• Over realisation or overstepping of promises (cognitive assessment, achievement more than agreed)

The psychological contract, according to its nature and its realization, gives coloration to the accompanying relationship and explains the degree of satisfaction of the entrepreneurs. It is especially in relation to the performance of the psychological contract that these results can be demonstrated. The perception of a discrepancy between the promise made and its realisation leads to a reassessment of the relationship established with the accompanying institution and its representatives. Finding that a promise is not kept (or is exceeded) generates an emotional reaction, and consequently a reassessment of the foundations of the accompanying relationship. The first reaction to a rupture is to reduce the level of confidence in the one who broke the involvement. But the consequences go far beyond the loss of confidence. In an entrepreneurial environment, the danger is a decline in emotional commitment (we no longer identify with values), or on the contrary an increased tendency to leave the newly created company.

The work analysed on the entrepreneurial support relationship shows that the existence of the moral contract is necessary for the success of any interpersonal relationship. In this perspective, as part of his research and practice of program development insist that the psychological contract exists implicitly in the relationship of assistance or accompaniment. "The basis on which the two parties agree on the conduct of the accompaniment. It is important that a kind of moral contract be established specifying the objectives, the means to achieve them, the respective roles of the coach and his protégé and an action plan including a time frame [73,74]. This contract must allow the parties to manage and structure their relationship, while allowing some flexibility to adjust the firing along the way "P 5. Hence, we deduce and advance our third hypothesis:

Research Methodology

Method of data collection

To achieve our objectives, we chose to collect the data using a questionnaire for a sample of 350 Tunisian novice entrepreneurs. Contractors were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with the variable statements of our study. Then, these two components are measured by items on a Likert scale of five points.

Measurement of Variables

The trust construct

The trust construct, which, to our knowledge, has been the subject of only one operationalization in previous studies on the coaching relationship, that of Jean Etienne, 2008. According to this author, trust in the coach is based mainly on the personal qualities necessary to establish a relationship of trust. After a review of the literature, we defined this construct as follows. The relationship of trust is based on personal qualities such as honesty, ability to keep promises, discretion, openness, loyalty, behavioural stability, interpersonal knowledge and skills, communication and frequency of meetings between the two parties. Empirical research that has focused on the operationalization of interpersonal trust is numerous in management science. However, some modifications have been made to the trust measurement scales identified in the works of Hosmer, Meyer et al., Geindre Morgan and Hunt, Das and Teng and Doney and Cannon so that they can be adapted to our study context. Therefore, following the example of Jean Etienne, we use the following measurement scale for the confidence perceived by the novice entrepreneur in relation to his coach. (I can trust my support person; my companion is a reliable person on whom I can rely; My support person behaves in a predictable way).

Entrepreneurial-accompanying relationship constructs

Our definition of the construct of the entrepreneurial-accompanying relationship is based on the research of those authors mentioned above the relationship between the attendant and the entrepreneur is an exchange relationship where the two parties benefit from each other's collaboration in terms of knowledge and experience. Among the few research on the accompanying relationship was the first to operationalize the accompanying entrepreneurial relationship [75-77]. The reliability of the resulting measurement scale is composed of nine items: it is considered very satisfactory. Therefore, we are adopting this measurement scale: (It allows me to make a precise picture of myself and my company; It secures me; He believes I can succeed as an entrepreneur; I consider him a friend; He puts me in touch with people he knows; It provides me with information and intelligence related to the business world; Confrontation he would not hesitate to contradict me if he did not agree; He offers me other points of view; He shows me his successes and failures).

The commitment construct

Most of the work in entrepreneurship on commitment borrows from human resource management. To define this construct, we based ourselves on the work of Allen and Meyer. Commitment is a force that pushes the individual to persevere in a specific line of action and the way the individual perceives and gives meaning to his environment. Commitment is a construct that, to our knowledge, has been the subject of only one operationalization in previous studies in entrepreneurship that of P-value.

Following the example of the latter, we will take part of the Allen and Meyer) measurement scale to operationalize this construct: (It would be more costly for me to (re) change my companion than to stay with him or her I have invested too much in the relationship with my companion to consider (re) changing my companion; (Re) changing my companion would require too many material and financial sacrifices; My life would be too disrupted if I gave up my companion now; I am proud of my companion; I feel a responsibility to continue with my support person; I would feel guilty if I gave up my support person; I feel a moral obligation to stay with my support person; Even if I found benefits, I think it would not be appropriate to change my support person.)

The existence of a psychological contract constructs

In defining the variable "the existence of a psychological contract," we relied on the work of the psychological contract can be defined as a moral contract that connects two parties (the contractor and the attendant). Its existence makes it possible to study the exchange through mutual promises and obligations. The existence of the psychological contract is a construct which, to our knowledge, has never been operationalized in previous studies in entrepreneurship. For this, we will take up part of the measurement scale of with a slight modification necessary to our subject of study. (1 your attendant has made to you, explicitly or implicitly, a number of promises; 2 you believe that these promises have been fulfilled).

Data analysis

After collecting data from 350 Tunisian entrepreneurs, we analysed their answers concerning the impact of the entrepreneurs' commitment, the existence of the psychological contract and the entrepreneur trust on the success of the entrepreneurial support relationship. The data processing is done through structural equation modelling, via PLS regression, using the Smart-PLS.02 software.

Estimation of the model by structural equations

To test our hypothesis through PLS regression. We started with the evaluation of the measurement model, followed by the evaluation of the structural model, as well as the estimation of the results for our hypothesis raised in this study.

The measurement model

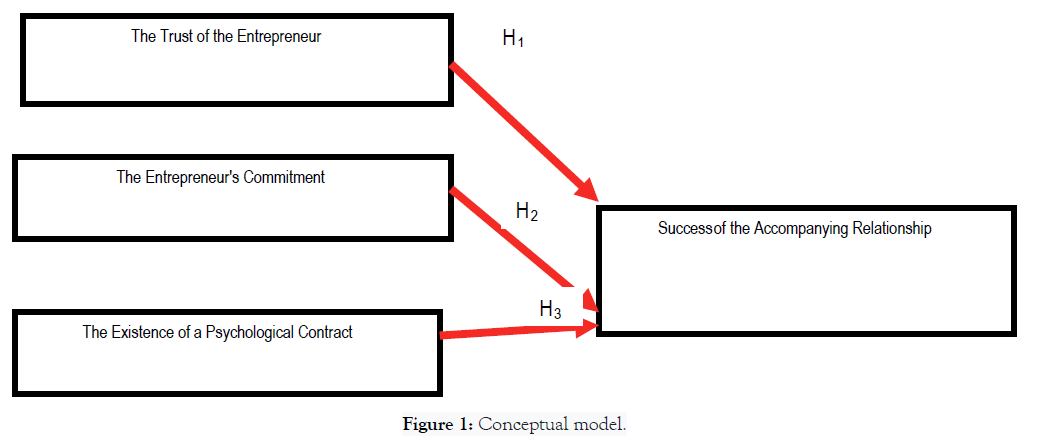

This model represents the linear relationships between the constructs and their indicators (Figure 1). To test the measurement model, we adopted three evaluation methods:

Figure 1: Conceptual model.

Reliability

This involves testing the reliability of each of the variables in our research model. Specifically, to measure the internal consistency of our research constructs. This is ensured by checking the Cranach’s alpha of the construct (the minimum alpha threshold is 0.7), and especially the composite reliability (CR), which is considered superior to the traditional measure of consistency (Cronbach's alpha), because it does not depend on the number of indicators [78].

From the analysis of the table below, it is apparent that our composite reliability (CR) indicators are all above the acceptance threshold (0.7). Sufficient reliability to justify a very high level of internal consistency. Similarly, the Cranach’s alpha values of our constructs are very satisfactory and are above 0.9 (Table 1).

| Constructs | Composite Reliability (CR) | The Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Existence of the Psychological Contract | 0,848858 | 0,745301 |

| The entrepreneurs' commitment | 0,937544 | 0,927006 |

| The trust of the entrepreneur | 0,942116 | 0,907687 |

| Success of the accompanying relationship. | 0,973685 | 0,969400 |

Table 1: Reliability of constructions.

Convergent validity of constructions

Taking into account the criticisms addressed to the Alpha coefficient, particularly its sensitivity to the number of items, it is advisable under the PLS approach to complete the verification of the convergent validity of the constructed by using two other indicators. The first is that we will purify the variables by retaining only indicators with a correlation threshold > 0.7 [79]. The second is that we will examine the average shared variance (AVE) that should be > 0.5. To achieve this, simply calculate the PLS algorithm that generates the following results (Table 2).

| Construct | Item's | Loodings | AVE | Composite Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The trust of the entrepreneur | CONF1 | 0,891067 | 0,844506 | 0,942116 |

| CONF2 | 0,904235 | |||

| CONF3 | 0,960143 | |||

| Existence of the Psychological Contract | CONTRPSY1 | 0,839379 | 0,737502 | 0,848858 |

| CONTRPSY2 | 0,877751 | |||

| Normative Commitment | ENGN1 | 0,942347 | 0,901053 | 0,973234 |

| ENGN2 | 0,987506 | |||

| ENGN3 | 0,926722 | |||

| ENN4 | 0,987506 | |||

| Calculated commitment | ENGC1 | 0,958843 | 0,973701 | 0,993291 |

| ENGC2 | 0,995895 | |||

| ENGC3 | 0,995895 | |||

| ENGC4 | 0,995895 | |||

| Affective commitment | ENGA1 | 0,964293 | 0,924292 | 0,979918 |

| ENGA2 | 0,974851 | |||

| ENGA3 | 0,974851 | |||

| ENGA4 | 0,879591 | |||

| Success of the entrepreneurial coaching relationship | REACC1 | 0,802931 | 0,804659 | 0,973686 |

| REACC2 | 0,909251 | |||

| REACC3 | 0,913278 | |||

| REACC4 | 0,915418 | |||

| REACC5 | 0,907314 | |||

| REACC6 | 0,933339 | |||

| REACC7 | 0,927569 | |||

| REACC8 | 0,903458 | |||

| REACC9 | 0,852916 |

Table 2: The converging validity of the constructs.

According to the table above, the convergent validity is ensured since all the items have a correlation threshold > 0.7 (the loadings >0.8) and an average shared variance value (AVE) greater than 0.5 (they vary from 0.9 to 0.80). This last indicator allows us to ensure both the convergent validity of the constructs [80]. The discriminant validity.

Evaluation of the quality of the model

To judge the quality of the model under the PLS approach; there is no index that allows us to test the quality of the model in its entirety. Nevertheless, three validation steps are allocated in the literature to assess the quality of the model: the quality of the measurement model, the quality of the structural model, and the quality of each structural equation.

Assessing the quality of the measurement model

First, we note that we evaluated our structural model without the mediating variables. To examine the model quality of the measure, we observe the coefficient of determination (R²) values of each of the dependent variables. This coefficient also allows us to estimate the predictive power of the research model.

The results found generated by the PLS algorithm technique, show that all the variables introduced to our model globally explain (R=48.2%) the entrepreneur-accompanist relationship. According to the size of our sample which can be considered as a high size, we can see that the R² respects the minimum limit of 0.13 suggested by Wetzels R [81]. Thus, the value constitutes an acceptable result and indicates that our model is significant.

Quality assessment of each block of variables

As we have previously stated, the Stone-Geisser Q² coefficient (cvredundancy) of the endogenous variables allows us to examine the quality of each structural equation. Therefore, to assess this index we had recourse to the Blindfolding technique under the SmartPLS software, the results found show us that the Q² indices are positive and different from zero for the accompanying contractor relationship (0.147). These results indicate that the model has predictive validity.

Evaluation of the quality of the structural model

To evaluate the quality of the structural model we will consider the value of the GOF index. This index is calculated through the average of communality and the average of R² of the endogenous variables. So the GOF index is calculated by:

GOF=√ communality × R²

GOF=√ (0.7590865) * (0.4402675)=0.5036.

This satisfactory result allows us to proceed to the next step of data analysis.

Validation and evaluation of the structural model

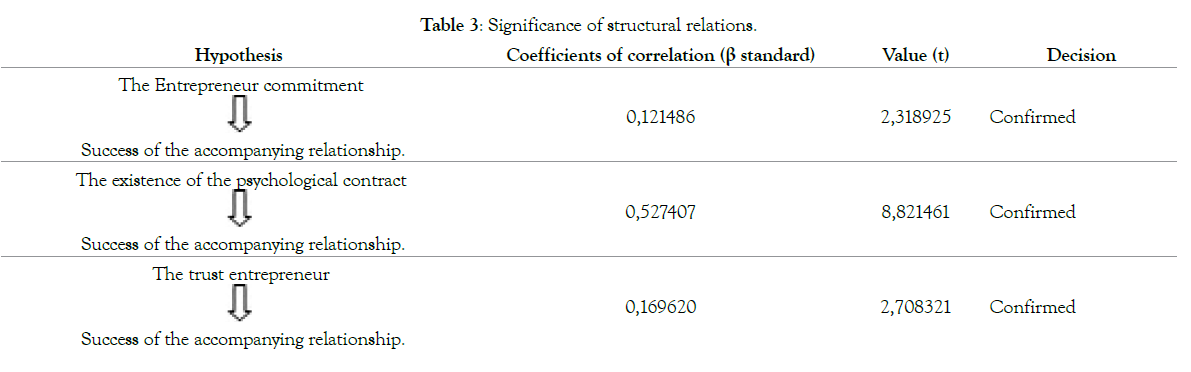

This paragraph has as objective the evaluation of the structural model, thus, we emphasize the test of the formulated hypotheses. To do this, two non-parametric techniques are used in the PLS approach: the jackknife technique or the bootstrap technique. In this study we used the bootstrap replication analysis (n=350, 500 iterations) states that the jackknife is less efficient than the bootstrap in the sense that it is only an approximation, the bootstrap being a more recent resampling method. Therefore, to test the significance of the structural relationships, we use the bootstrap procedure (sample=500; n=350) by saturating the model. The results obtained are presented in Table 1 where the first column shows the relationships related to our hypotheses that are significant. The second and third columns show the values of the regression coefficients and Student's t respectively. The latter must be >2.58 for a significance level α=1%, >1.96 for an α=5%, or >1.65 for an α=10% (Table 3).

Table 3: Significance of structural relations.

The analysis of these found results allows us to confirm our research hypothesis. The statistical test highlights a significant relationship between the entrepreneur's commitment and the entrepreneurcoach relationship, thus this hypothesis is validated (t=2.318'1.96; β =0.121). The fact that the entrepreneur is committed to the coach influences the success of the coaching relationship. Also, the results of the Bootstrap analysis also demonstrate that the entrepreneur's trust in the coach is significantly and positively related to the entrepreneur-coach relationship, hypothesis is validated (t=2.708'1.96; β =0.170), the more trust the entrepreneur shares in the coach, the more positive the coaching relationship is. Similarly, our analysis shows the existence of a significant and positive link between the psychological contract and the entrepreneur-coach relationship. The hypothesis is validated (t=8.821'1.96; β =0.527), the existence of the promises and the realization of the latter favors the success of positively the entrepreneur-accompanist relationship. Analysis of these found results allows us to confirm our research hypothesis.

Discussion

Trust by the entrepreneur appears to be a determinant that has a significant influence on the entrepreneur-mentor relationship. This result is consistent with those of several researchers Audrey Assoune Kram; Allen and Eby, Ensher and Murphy, Wanberg et al., who indicate that trust, plays a role in the coaching relationship. Similarly, Geertjan Weijman and Etienne St-Jean et al. also on several occasions have confirmed the positive impact of the entrepreneur's trust on the success of the entrepreneur-coach relationship.

So, the trust of the entrepreneur towards his coach seems important for the success of the relationship, because the entrepreneur by expressing their trust recognizes what the other knows how to do or what he should know, i.e., he evaluates or judges positively the capabilities of his coach. Indeed, the reliability and benevolence of the coach are extremely important factors for the entrepreneur, because in any relationship the entrepreneur must be convinced that the coach will take into account the best interests of the coaches and that he will not act in his own interest. In the same way, the ability to listen and the empathy perceived in the coach are considered as essential conditions, even primordial, that favor the trust of the entrepreneur.

The validation of the second hypothesis confirms the theoretical advances previously discussed. Indeed, the empirical validation of this relationship in previous research in entrepreneurship is almost absent. However, theoretical advances on commitment and the coaching relationship present the entrepreneur's commitment as a determining factor in the success of the relationship, but without defining or measuring it. In this regard, C. Bruayt, Fayolle et al., Laura Gaillard, Giordani, Audrey Assoune, Valeau and Etienne St-jean indicate that the more entrepreneurs are committed, the more the benefits of the relationship are assured and obtained. In short, these results offer an answer to the theoretical advances that opened the way to such a possibility for the first time to our knowledge.

In the same way, our study notes the important role played by the psychological contract with respect to the coaching relationship. This finding confirms the results of previous theoretical studies in entrepreneurship on this subject. Like the variable commitment, we do not find empirical studies that have demonstrated the effect of the psychological contract on the coaching relationship. Indeed, our results are consistent with the work of authors Paul Couteret and Josée Audet, Etienne ST-Jean that concluded that the existence and fulfilment of the promises announced discriminating condition in the success of the coaching relationship. These results are particularly important because this relationship, which to our knowledge has never been tested, offers an answer to the theoretical literature that opened the way to such a possibility Paul Couteret and Josée Audet, Etienne St-Jean.

Conclusion

The results obtained helped to answer the questions of this research. Firstly, the results show the importance of three factors in the success of the coaching relationship: the commitment of the entrepreneur to his coach, the perceived trust of the entrepreneur in his coach and the existence of the psychological contract. In fact, these three factors contribute to the success of the relationship by promoting and/or facilitating the coach to carry out the main functions assigned to him. In this respect, the results show that the three factors positively influence the success of the coaching relationship. The statistical analysis confirmed the existence of a positive and significant link between the entrepreneur's confidence in his coach and the coaching relationship. In addition, the results also highlighted the existence of a positive and significant link between the entrepreneur's commitment and the coaching relationship: entrepreneur-coach. Similarly, the results show a positive and significant link between the existence of the psychological contract and the coaching relationship: entrepreneurcoach.

The present research provides results that, for the most part, have not been previously demonstrated. The contribution of this research is that, although other research has previously sought to determine the antecedents of the coaching relationship: entrepreneur-coach by factors related only to the personal characteristics of the member of dyad entrepreneur-coach. This research contributes to enrich the studies and to develop a theoretical model to explain and predict the success of the entrepreneur-mentor relationship by psychological factors related to the entrepreneur (the commitment of the entrepreneur, the perceived confidence and the existence of the psychological contract). Indeed, this study has shown, in the first place, the determining role of the entrepreneur's commitment to his business in the success of the entrepreneurial support relationship. In a second place, this research also contributed to validate the effect of the trust perceived by the entrepreneur towards his coach on the success of the entrepreneurial coaching relationship. Finally, this result highlights the role that the existence of a psychological contract plays in the success of the coaching relationship.

From a managerial point of view, our work contributes to a more precise and concrete knowledge of the entrepreneurial coaching relationship, which is not only dependent on the degree of commitment of the novice entrepreneur, the perceived trust and the existence of a psychological contract between the entrepreneur and the coach, but also on the adequacy of the personal characteristics of both parties. Thus, for entrepreneur coaches, it is very useful to know how to manage this relationship. They must understand the importance of psychological determinants in the success of their coaching relationship. They must also recognize the importance of the interaction between the different partners involved in the relationship. This knowledge can help coaches to remove some of the unknowns in the failures of newly created businesses despite their coaching.

Our research cannot avoid operational limits. However, these may become, at a later stage, avenues for further research. Our research has mobilized the questionnaire technique. This traditional tool has its limits even if they do not call into question the fundamental results obtained. Indeed, the questionnaire and the measures used may appear somewhat simplistic in the face of a highly complex reality. Although the measures used present satisfactory results. Our survey was conducted only with entrepreneurs and ignored the opinion of the coaches involved in a coaching relationship. Due to the methodological difficulties linked to the treatment of this issue.

Another limitation concerns the notion of time, which was not considered. Indeed, a coaching relationship evolves over time. The survey of entrepreneurs gathered all the entrepreneurs interested in answering the questionnaire, some of whom were at the beginning of their relationship and for others, it had ended. By pairing in dyad with the opinions of the coaches, this could induce certain distortions.

In the end, we suggest analysing and comparing these results with uncoated entrepreneurs. Also, among the stakeholders of the support structures, we have questioned in this research only the entrepreneurs, hence we propose to integrate the opinion of the coaches or other stakeholders of these support structures in further studies. Finally, we plan to apply this evaluation to other structures in other countries in order to verify the possible generalization of our results.

REFERENCES

- Minot VE. État Des Lieux Et Perspectives Du Marché Des Cessions-Transmissions De Pme En France, Thèse Professionnelle, Hec. 2016.

- Schmitt C, Grégoire Da. La Cognition Entrepreneuriale. Enjeux ET Perspectives Pour La Recherche En Entrepreneuriat. Revue De Lentrepreneuriat. 2019;18(1):7-22.

- Messeghem K, Sammut S, Chabaud D, Carrier C, Thurik R. L'accompagnement Entrepreneurial, Une Industrie En Quête De Leviers De Performance ? Manag International. 2013;17(3):65-71.

- Degeorge Jm. From the Diversity of the Entrepreneurial Coaching Process towards a Better Complementarity. Revue De L'entrepreneuriat. 2017;17(2):7-15.

- Wolff D. Cuénoud T. Pour Une Approche Renouvelée De L'accompagnement Des Créateurs Et Des Repreneurs D'entreprise: Le Coaching Entrepreneurial Vie & Sciences De L'entreprise. 2017;2(204):146-163.

- Dupouy A. Accompanying the Innovative Project Leader. Or How To Make His Competencies Emerge. Projectics/Proyéctica/Projectique. 2008;(1):111-125.

- Bruyat C. Business Creation: Epistemological Contributions And Modelling. Doctoral Thesis. Université Pierre Mendès-France-Grenoble Ii. 1993.

- Brédart X, Bughin C, Comblé K. The Impact of Governance on Involvement in a Csr Approach in a Company. Recherches En Sciences De Gestion. 2019;(3):291-315.

- St-Jean E, Audet J. Factors Leading To Satisfaction In A Mentoring Scheme For Novice Entrepreneurs. International Journal of Evi Based Coaching & Mentoring. 2009;7(1).

- Couteret P, Audet J. Coaching, As a Mode of Support for the Entrepreneur. Revue Internationale De Psychosociologie. 2006;12(27):139-157.

- Pezet É, Le-Roux A. La Nébuleuse De L'accompagnement: Un Palliatif Du Management? Management Avenir. 2012;(3):91-102.

- Levy-Tadjine T. Peut-On Modéliser La Relation D'accompagnement Entrepreneurial? La Revue Des Sciences De Gestion. 2011;5:83-90.

- Cuzin R, Fayolle A. Les Dimensions Structurantes De L'accompagnement En Création D'entreprise. La Revue Des Sciences De Gestion: Direction Et Gestion. 2004;39:210-77.

- Valéau P. Supporting Entrepreneurs During Periods Of Doubt. Revue De Lentrepreneuriat. 2006;5(1):31-57.

- Rice MP. Co-Production De L'aide Aux Entreprises Dans Les Incubateurs D'entreprises : Une Étude Exploratoire. Journal of Bus Venturing. 2002;17(2):163-187.

- Covin TJ, Fisher TV. Consultant And Client Must Work Together. Journal of Manag Consulting. 1991;6(4):11-20.

- King P, Eaton J. Le Coaching Au Service Des Résultats. Formation Industrielle Et Commerciale. 1999.

- Makaoui N. La Confiance Inter-Organisationnelle : Essai De Conceptualisation Et Proposition De Mesure. Question(S) De Management. 2014;(3):39-60.

- Smith J. Brock B, Donald W. The Effects of Organizational Differences and Trust on the Effectiveness of Selling Partner Relationships. Journal of Marketing. 1997;61(1):3-21.

- Gurviez P, Korchia M. Proposition D'une Échelle De Mesure Multidimensionnelle De La Confiance Dans La Marque. Recherche Et Applications En Marketing (Edition Française). 2002;17(3):41-61.

- Singh J, Sirdeshmukh D. Mécanismes D'agence Et De Confiance Dans Les Jugements De Satisfaction Et De Fidélité Des Consommateurs. Journal of the Academy Of Mark Science. 2000;28(1):150-167.

- Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD. Un Modèle Intégratif De La Confiance Organisationnelle. Academy Of Manag Review. 1995;20(3):709-734.

- Bachmann R, Zaheer A. Handbook of Trust Research. Edward Elgar Publishing. 2006.

- Anderson JC, Narus JA. A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships. Journal of Marketing. 1990;54(1):42-58.

- Mériade L. L'hybridation Des Instruments De Gestion. L'exemple Du Pilotage De La Performance Universitaire En France. Management Avenir. 2019;2:13-42.

- Williams R. The Long Revolution. Broadview Press. 2001.

- Jeffries FL, Reed R. Trust and Adaptation in Relational Contracting. Academy Of Manag Review. 2000;25(4):873-882.

- Mcallister DJ. Affect-And Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations. Academy Of Manag Journal. 1995;38(1):24-59.

- Barney JB, Hansen MH. Trustworthiness as a Source of Competitive Advantage. Strategic Manag Journal. 1994;15(1):175-190.

- Doney PM, Cannon JP. An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Marketing. 1997;61(2):35-51.

- Khalifa AH, Kammoun MM. La Confiance Interpersonnelle Et La Confiance Organisationnelle Dans La Relation Client-Prestataire De Service: Cas De La Relation Client-Banque. La Revue Des Sciences De Gestion. 2013;3:167-174.

- Rousseau DM. Le "Problème" Du Contrat Psychologique Considéré. Journal of Org Behavior. 1998;665-671.

- Garbarino E, Johnson MS. The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships. Journal of Marketing. 1999;63(2):70-87.

- Lewis J, David W, Andrew J. The Social Dynamics of Trust: Recherches Théoriques Et Empiriques, 1985-2012. Social Forces. 2012;91(1):25-31.

- N'goala G. Une Approche Fonctionnelle De La Relation À La Marque: De La Valeur Perçue Des Produits À La Fidélité Des Consommateurs. Thèse De Doctorat. Montpellier 2. 2000.

- Akrout W, Akrout H. Trust in B To B: Towards A Dynamic And Integrative Approach. Recherche Et Applications En Marketing (French Edition). 2011;26(1):59-80.

- Ring PS. La Confiance Fragile Et Résiliente Et Leurs Rôles Dans L'échange Économique. Business & Society. 1996;35(2):148-175.

- Morgan RM, Hunt SD. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing. 1994; 58(3):20-38.

- St-Jean E, Josée A. "Factors Leading To Satisfaction in a Mentoring Program for Novice Entrepreneurs". International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching & Mentoring. 2009;7(1).

- Sammut S. L'accompagnement De La Jeune Entreprise. Revue Française De Gestion. 2003;(3):153-164.

- Dalley J, Hamilton B. Knowledge, Context and Learning in the Small Business. International Small Bus Journal. 2000;18(3):51-59.

- Couteret P, St-Jean E, Audet J. Le Mentorat: Conditions De Réussite De Ce Mode D'accompagnement De L'entrepreneur, 23rd Ccpme/Ccsbe Conference, Trois-Rivières, Québec. 2006;28-30.

- Bhattacherjee A. Individual Trust In Online Firms: Scale Development and Initial Test. Journal Of Manag Inf Systems. 2002;19(1):211-241.

- Cranwell-Ward J, Bossons P, Gover S. The Differences between Mentoring and Coaching. In: Mentoring. Palgrave Macmillan, London. 2004;45-47.

- Mitrano-Méda S, Véran L. Une Modélisation Du Processus De Mentorat Entrepreneurial Et Sa Mise En Application. Management International/International Management/Gestión Internacional. 2014;18(4):68-79.

- Chun JU, Litzky BE, Sosik JJ. Emotional Intelligence and Trust in Formal Mentoring Programs. Group & Org Manag. 2010;35(4):421-455.

- St-Jean E, Lebel L, Audet J. Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Forestry Industry: A Population Ecology Perspective. Journal of Small Bus and Enterprise Dev. 2010.

- Dupouy A, Pilnière V. Accompaniment of the Innovative Project Owner and Implementation of His or Her Skills Development Process. 10th International Francophone Congress on Entrepreneurship and Smes. 2010.

- Berger-Douce S, Valenciennes IAE. L'accompagnement Des Éco-Entrepreneurs: Une Étude Exploratoire. 8th International Francophone Congress on Entrepreneurship and Smes. 2006.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ. A Three-Component Conceptualization of Organizational Commitment. Human Res Manag Review. 1991;1(1):61-89.

- Giordani LG. Dinamica Del Commitment Di Risorse E Creazione Di Nuove Imprese. 2005.

- Valéau P. L'engagement Des Entrepreneurs: Des Doutes Au Second Souffle. Revue Internationale Pme Économie Et Gestion De La Petite Et Moyenne Entreprise. 2007;20(1):121-154

- Valéau P. The Effects of Affective, Continuous and Normative Commitment on the Intention to Remain In the Entrepreneurial Profession. Revue De Lentrepreneuriat. 2017;16(3):83-106.

- Alexis C, Karim M, Sylvie S. Development and Validation of a Scale for Measuring the Export Support of Smes. International SME Review. 2015;28(1):117-156.

- Cull J. Mentoring Young Entrepreneurs: What Leads To Success?", International Journal Of Evi Based Coaching And Mentoring. 2006;4(2):8-18.

- Gravells J. Mentoring Start-Up Entrepreneurs In The East Midlands – Troubles hooters And Trusted Friends, The International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching. 2006;4(2).

- Simard P, Julie F. Mentoring Entrepreneurs. Gestion. 2008;33(1)10-17.

- Cook KS, Emerson RM. Power, Equity and Commitment in Exchange Networks. American Sociological Review. 1978;721-739.

- Young L, Denize S. A Concept of Commitment: Alternative Views of Relational Continuity in Business Service Relationships. Journal of Bus & Ind Marketing. 1995.

- Anderson E, Weitz B. The Use of Pledges To Build And Sustain Commitment In Distribution Channels. Journal of Marketing Research. 1992;29(1):18-34.

- Lockshin LS, Spawton AL, Macintosh G. Using Product, Brand And Purchasing Involvement For Retail Segmentation. Journal of Retailing and Con Serv. 1997;4(3):171-183.

- Wilson DT, Vlosky RP. Inter-organizational Information System Technology and Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of Bus & Ind Marketing. 1998.

- Lacœuilhe J. The Concept Of Attachment: Contribution To The Study Of The Role Of Affective Factors In The Formation Of Brand Loyalty. Doctoral Thesis. Paris 12. 2000.

- Cristau C. Definition, Measurement and Modelling of Brand Attachment with Two Components: Brand Dependence and Friendship. PhD Thesis. Aix-Marseille 3. 2001.

- Aaker DA. Building a Brand: The Saturn Story. California Manag Review, 1994;36(2):114-133.

- Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA. Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psy. 1993;78(4):538.

- Meyer JP. Herscovitch L. Commitment in the Workplace: Toward A General Model. Human Res Manag Review. 2001;11(3):299-326.

- Molm LD, Takahashi N, Peterson G. Risk and Trust in Social Exchange: An Experimental Test of a Classical Proposition. Amer J Social. 2000;5(105):1396-1427.

- Coyle-Shapiro J, Neuman J. Individual Dispositions and the Psychological Contract: The Moderating Effects of Exchange and Creditor Ideologies, Journal of Voc Behavior. 2004;64:150-164

- Rousseau D. Perceptions of New Employees and Their Employer Obligations: Study of Psychological Contracts. Journal of Org Behavior. 1990;11:389-400.

- Shore LM, Tetrick LE, Taylor MS, Coyle Shapiro JAM, Liden RC, Mclean PJ, e t al. The Employee-Organization Relationship: A Timely Concept in a Transitional Period: Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley. 2004;23:291-370.

- Cavanaugh M, Noe R. Antecedents and Consequences of the Relational Components of the New Psychological Contract. Journal of Org Behavior. 1999;20(3):323-340.

- Clutterbuck D. Communication and Psychological Contract. Journal of Communication Manag.2005;9(4):359-364.

- Covin TJ, Fisher TV. The Consultant and the Client Must Work Together. Journal of Manag Consulting. 1991;6:11-19.

- Audet J, Couteret P. Le Coaching Entrepreneurial: Spécificités Et Facteurs De Succès. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship. 2005;18(4):471-489.

- St-Jean E. Fonctions De Mentor Pour Les Entrepreneurs Novice. Journal De L'academy of Entrepreneurship. 2011;17(1):65.

- St-Jean É. The Duties of the Novice Entrepreneur's Mentor. Journal of Entrepreneurship. 2010;9(2):34-55.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural Equation Models With Unobservable Variables And Measurement Error: Algebra And Statistics. 1981.

- Fernandes V. In What Way Is The Pls Approach A Method To (Re)-Discover For Management Researchers? M @ N @ Gement. 2012;15(1):102-123.

- Chin WW. The Partial Least Squares Approach To Structural Equation Modelling. Modern Methods For Business Res. 1998;295(2):295-336.

- Wetzels R. How To Quantify The Support For And Against The Null Hypothesis: A Flexible Winbugs Implementation Of A Default Bayesian T Test. Psychonomic Bulletin And Rev. 2009;16(4):752-760.

Citation: Mohamed F, Zouaoui SK (2021) Psychological Determinants of the Success of the Entrepreneurial Support Relationship. Review Pub Administration Manag. 9:290.

Copyright: © 2021 Mohamed F, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.