PMC/PubMed Indexed Articles

Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- SafetyLit

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Article - (2020) Volume 9, Issue 1

Nurse Practitioner-Led Education: Improving Advance Care Planning in the Skilled Nursing Facility

Copley M* and Ingram CReceived: 08-Aug-2019 Published: 29-Jan-2020, DOI: 10.35248/2167-7182.20.9.507

Abstract

The Advance Care Planning (ACP) note is a critical component for guiding the care of patients in the Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF). Although ACP documentation is essential, it often is not completed in the SNF. The purpose of the project was to increase the number of ACP notes for patients admitted to 13 SNFs in Southeastern Minnesota. Prior to intervention, the ACP note was not consistently completed by the Nurse Practitioner (NP) or Physician Assistant (PA) in the SNF. The aim of the Quality Improvement (QI) project was to increase ACP note completion rates by 50% and increase satisfaction and knowledge with the ACP process amongst NPs and PAs over a 12-week period after the administration of a one-hour ACP education session. By improving the ACP process, patients can participate in a positive end-of-life experience and receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences. The hypothesis for this project was that a structured ACP process would increase the number of ACP notes completed compared to current processes. A secondary outcome was that structured ACP process would increase NP and PA satisfaction and knowledge with completing ACP notes. The design was a QI project that addressed the ACP process in 13 SNFs in Southeastern Minnesota. A convenience sample (N=10) of NP/PA providers completed a pre and post ACP education intervention survey. On all six survey questions, a general increase in mean value was demonstrated. Question two, seven and eight demonstrated the greatest increase in mean value score of (0.7, 1.2, and 0.9) respectively. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test elicited significant change in knowledge (p=0.037), understanding of ACP note billing (p ≤ 0.001), and satisfaction with ACP note documentation (p=0.004). Unfortunately, the QI project demonstrated a 2% decrease in ACP note documentation in the post-intervention phase. Although there was not a significant change in the ACP note completion rates, an improvement in NP/PA knowledge and satisfaction was demonstrated through ACP education session.

Keywords

Advance care planning; Skilled nursing facility; Satisfaction; Knowledge; Education; Documentation

Introduction

Nurse practitioner-led education and improving advance care planning in the skilled nursing facility caring for patients with chronic medical conditions can be challenging for a health care provider if the patient’s medical wishes are unknown. As health care technologies evolve, advances in medicine result in Americans living longer with greater health burdens. Mueller, Hook, and Fleming stated “an elderly person has, on average, 3 to 4 chronic illnesses and a nearly 20% annual risk of hospitalization” [1-3]. Although advances in medical technology are allowing for individuals to live longer with more chronic illnesses, Advanced Care Planning (ACP) has been left at the wayside and patient’s health wishes often would go undocumented and unrecognized.

In America, a majority of patient’s report being comfortable and pain-free is important when approaching the end-of-life [4]. Although many patients express a preference for a natural death that is comfortable and pain-free, barriers exist in the care patients receive in the last six months of life [4]. To overcome these barriers, it is essential to improve communication processes, education techniques, and interventions for initiating ACP with patients. Advance care planning is a critical component of the end-of-life conversation. As defined by Detering and Silveira “the goal of ACP is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals, and preferences” [2]. Advance care planning involves a discussion of an individual’s care preferences. Documentation of the conversation is critical so that the patient’s wishes are honored [5]. By improving the ACP process, patients can participate in a positive end-of-life experience and receive the treatment according to their preferences [1].

In the Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF), patients are required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to have an initial comprehensive assessment in which a complete physical examination is completed, a care plan is developed, and admission orders are signed [6]. The visit must be completed by the physician no later than 30 days from admission to the SNF (CMS, 2012). After the initial physician visit has been completed, the physician can delegate to a qualified Nurse Practitioner (NP) or Physician’s Assistant (PA) to continue to provide care to the patient at the SNF [6]. As part of the initial and subsequent care visits, the physician, NP, or PA is responsible for conducting the ACP conversation and documentation of the ACP note with the patient and family.

To comply with CMS regulations, a physician’s group within the department of Community and Internal Medicine (CIM) at a large midwestern teaching hospital created the advance care planning care process model for outreach programs. Outreach programs at the organization include the SNF and homebound care programs. Assumptions outlined in the process model focus on the importance of ACP for this specifically high-risk population that is at above average risk for hospitalization, functional decline, and mortality [7]. As part of the CIM ACP process model outlined by Hanson, “all patients will have an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) ACP note completed within 30 days of admission to the SNF and updated annually, or with any major change in condition or prognosis” [7].

The aim of the Quality Improvement (QI) project was to increase ACP note completion rates by 50% and increase satisfaction and knowledge with the ACP process amongst NPs and PAs after the administration of a one-hour ACP education session. It was identified that future ACP education for NP/PA providers was needed to provide a more robust understanding of the ACP process and documentation. Also, future endeavors would include data collection and providing education for the physicians completing ACP notes in the SNF. Although education was well received, no policy changes were made from this education, but rather positive reinforcement for the need to complete ACP notes for all patients admitted to the SNF.

Problem statement

Prior to intervention, SNF patients have been noted to be subjected to unwanted, unnecessary, and avoidable hospitalizations and Emergency Department (ED) visits resulting in increased healthcare costs and poor quality of care [5]. A lack of documented patient wishes can also result in a negative end-of-life experience and unwanted medical care for patients and their families [5].

Clinical question

The guiding clinical question for this project was: “In patients who reside in SNFs in Southeastern Minnesota (P), can a structured ACP process model and ACP education (I), improve ACP note completion rates by 50% and demonstrate increased satisfaction and knowledge from NPs and PAs (O), compared to current practices (C) over a 12-week period (T)” The primary outcome will be the number of ACP notes completed by NPs and PAs following the intervention. The secondary outcome measured will be satisfaction and knowledge from NPs and PAs regarding the ACP note completion process.

The hypothesis for this project was that a structured ACP process would increase the number of ACP notes completed compared to current processes. Also, for secondary outcomes, the hypothesis was that the structured ACP process would increase NP and PA satisfaction and knowledge with completing ACP notes. With this project, there was also the possibility of a null hypothesis that would result in no significant changes demonstrated through the ACP process and interventions.

Theoretical framework

One way to improve the ACP process is to incorporate a theoretical model that offers guidance and empirical evidence for a standard model of care. The stages of change transtheoretical model of health behavior change is a five-stage change process that includes: Precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and termination [8].

The first stage of the transtheoretical model is pre-contemplation. In the work by Ernecoff, Keane and Albert, during the precontemplation stage, the individual has not even considered the ACP process or is not aware of the concepts of ACP [9]. Individuals in the pre-contemplation stage are not engaged in ACP on any level. The second stage is the contemplation stage. Rizzo et al. identifies the contemplation stage as a period where a person contemplates about the possibility of change [8]. It is important to understand that during the second stage the thought of ACP has occurred by the individual, but no action has been taken.

The third stage of the transtheoretical model is the preparation stage. The preparation stage involves an individual identifying that they intend to make a change. Ernecoff et al. applies this stage by having a formal discussion of end-of-life decisions and treatment preferences with healthcare providers, family members and the person who will be the Durable Power of Attorney (DPOA) [9].

The fourth stage known as the change/action stage involves the individual producing clinically significant behavior change [8]. In the ACP process, the action stage involves completion of the ACP conservation and the individual’s treatment preferences and wishes are documented. Once the ACP conversation and documentation has been completed, the individual is in the maintenance stage. The maintenance stage involves updating the document annually and continuing to have the DPOA updated about the individual’s health care wishes and preferences [9].

Literature Review

A review of the literature was conducted utilizing CINAHL, MedLine, PubMed and EBSCOhost. Keywords used in the search were advance care planning, end-of-life-conversation, communication, elderly, geriatrics, satisfaction, hospitalization, goals of care, and emergency room. The search only included articles in the English language. The search was initially restricted to the years 2012-2017 but was later expanded to the year 2000 to allow for more robust data collection. After the search was limited to systematic review, Randomized Control Trials (RCT) and meta-analyses, there was approximately 300 articles reviewed. After reviewing abstracts for relevance to this QI project, only eight articles were utilized. Many articles were excluded as they were unrelated to topic or there was a lack of evidence supporting the topic.

Lack of knowledge

A common theme throughout the literature was a lack of knowledge about ACP amongst patients, families, and healthcare staff [10]. In the literature, the lack of knowledge about ACP was multifactorial. The first area of deficiency stems from patients and families not being cognizant of the significance of ACP and assumptions are often made that the physician or healthcare provider will initiate the ACP conversation [11]. Another area that demonstrates a lack of knowledge about ACP was the many different types of ACP documents used in SNFs [12]. Families and nursing staff lack the understanding about the difference in the Advance Directive (AD), Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form or living wills. There was often confusion in the definition of do not resuscitate, do not intubate, and do not hospitalize [12].

To remedy the lack of knowledge in ACP, studies have demonstrated valuable information that can help improve the ACP process for both healthcare workers and patients. In a study conducted by Ahluwalia et al., providers differed in how they defined or even approached ACP with primary care providers defining it as more of a broad process and acute care providers defining more specific aspects of ACP and its relevance to practice [13]. Another study conducted by Weathers et al. reported patients and families involved in the ACP process demonstrated an increased knowledge about the ACP decisions and treatment options [14].

Rate of ACP completion

Historically, the ACP process has low completion rates. In an RCT conducted by Sinclair et al., demonstrated that patients who participated in nurse facilitated ACP discussion there was an increase in ACP uptake after 6 months [15]. As outlined by Sinclair et al. advance care planning uptake was significantly higher (p ≤ 0.001) in the intervention group (54 out of 106,51%), compared to usual care (6 out of 43,14%) [15].

In a controlled trial study by Jacobsen, Robinson, Jackson, Meigs, and Billings a multifaceted Quality Improvement (QI) project included five interventions to improve ACP [16]. The interventions included (a) nursing and physician education about how to approach ACP, (b) 15 minutes of dedicated time to discuss ACP during daily interdisciplinary team rounds, (c) palliative care physician involvement during interdisciplinary team rounds and with house staff, (d) the selective identification of patient who might benefit from focused discussions about ACP, and (e) focused ACP discussions (information sharing meetings and/or decision-making meetings) with patients and families, led by either interdisciplinary staff or residents [16]. Over a six-month period, 899 patients were included in the analysis of which 382 were on the control floor and 517 patients were on the intervention floor. Overall, the intervention floor had a greater number of patients participate in the goals of care discussion (33.8% intervention vs. 21.2% control, p ≤ 0.001). The ACP model that was utilized to increase uptake in the discussion of goals of care with patients was multifaceted, included various ACP models, and included information sharing and decision-making concepts [16].

Satisfaction

In the literature, the measurement of satisfaction with the ACP process was sparse. In a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Houben et al., seven studies reported satisfaction as an outcome from ACP [11]. In three of seven trials, family members of patients who completed ACP intervention reported having more satisfaction with the end-of-life care involving their loved one. Also, families in the intervention group described having a more thorough discussion about end-of-life care when compared to the control group; Houben et al. also reported in two of the seven trials that patients involved in the ACP intervention group reported having greater satisfaction with healthcare compared to the control group [11].

Another trend reported in multiple studies was that ACP was not associated with increased mortality, but rather improvements in quality of life and satisfaction from patients, families and medical staff [12]. This also correlated to the findings from Houben et al. and Hanson et al. in that the lack of ACP conversations often resulted in the critical conversation occurring during a crisis situation, which resulted in patient’s wishes not being fulfilled and leading to distress [11,17].

After an extensive review of the literature, the conclusion that was drawn from multiple analyses and studies was that there was not a standardized system or tool to measure patient, family, and nurse satisfaction. A majority of studies reviewed in the literature reported an increase in satisfaction, but no formal instrument or tools were utilized. The increase in satisfaction was demonstrated through verbal reports from family and have no statistical significance reported.

Healthcare services utilization

Another outcome that was prevalent in the literature related to ACP and SNF patients was hospitalization rates. Approximately 90% of patients admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) do not have an advance directive completed [1]. In Houben et al. meta-analysis, it was found that patients in the intervention group demonstrated an increased likelihood of receiving end-of-life care in concordance with their preferences (OR 4.66; 95% CI 1.20, 18.08; p=0.03) compared to the control group [11].

In a systematic review of 13 studies, Martin et al., reported that an ACP note decreased hospitalization rates by 9%-26% [12]. Although there was a significant decrease in hospitalization rates, there was no association with increased mortality. The review also found an increase in the number of patients dying in nursing homes by 29%- 40% who participated in ACP interventions. The percentage of patients dying in the skilled nursing facility was significant because it indicated that unnecessary hospitalization was avoided, and the resident was allowed to remain at the skilled nursing facility. Not only is ACP beneficial for reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and ED visits, but it can also increase utilization of necessary supportive services for patients. One study found that ACP demonstrated no change in the number of hospice referrals, but there was a 23.7% increase in community palliative care referrals [12].

Organizational alignment

The organization was in agreeance with the need for promoting ACP in the community, specifically in the SNF setting. The project also had buy-in from key stakeholders in the Southeastern Minnesota community because the project was innovative and added value to healthcare for members in the community. The project partnered with geriatricians at the organization who were in agreeance with increasing ACP notes and conversations in the community SNFs.

Another point to note about this project was that it was an extension of the ACP process that the primary healthcare organization had implemented. A new ACP process had been recently introduced in the outpatient settings prior to implementation of this project and specifically in primary care. The project helps providers identify patients that would be appropriate to have a follow-up visit to address their ACP needs and establish a care plan for their chronic medical conditions. This process was anticipated to increase the quantity of ACP notes, POLST form completions, and help to identify patients that would benefit from creating a detailed ACP note.

This project aligned with the organization’s goals due to the great emphasis being placed on ACP completion in local SNFs. Also driving the organizational alignment and commitment to this project was the federal regulation that all individuals admitted to SNFs require designation of resuscitation status documented within the health record [6].

Research Methodology

Design and setting

The design was a quality improvement project that addressed the ACP process in 13 SNFs in Southeastern Minnesota. The six Sigma Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control (DMAIC) strategy was utilized to reduce variability and improve outcomes [18]. The intervention was conducted by the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) student. During the one-hour education session material presented included the definition of ACP, review of CIM ACP process model, screenshots taken from the electronic health care record documenting the step-by-step process of how to document the ACP note and ACP note billing codes. Prior to the nurse practitioner-led education session the NPs and PA completed a pre-intervention survey to measure understanding of ACP and satisfaction with the ACP process. The tool was created by the DNP student and project mentor based on previous ACP process development surveys. Following the ACP education session, the NPs and PA completed the same five-point Likert scale survey. The five-point Likert scale pre-and post-intervention surveys measured knowledge and satisfaction about the ACP process pre- and posteducation.

The primary objective of the intervention was to increase ACP note completion rates by 50%. The secondary objective was to demonstrate an increase in knowledge and satisfaction amongst NPs and PA with the ACP process. Following the educational intervention, ACP notes from 12-weeks prior to education intervention (June 24, 2018-September 9, 2018) and posteducation intervention (September 10, 2018-December 3, 2018) were examined.

Participants

The participants in the project intervention were nine NPs and one PA in the SNF practice. The convenience sample consisted of nine female providers and one male provider. Participants included in the study were NPs and a PA practicing in at least one of the 13 SNFs in Southeastern Minnesota.

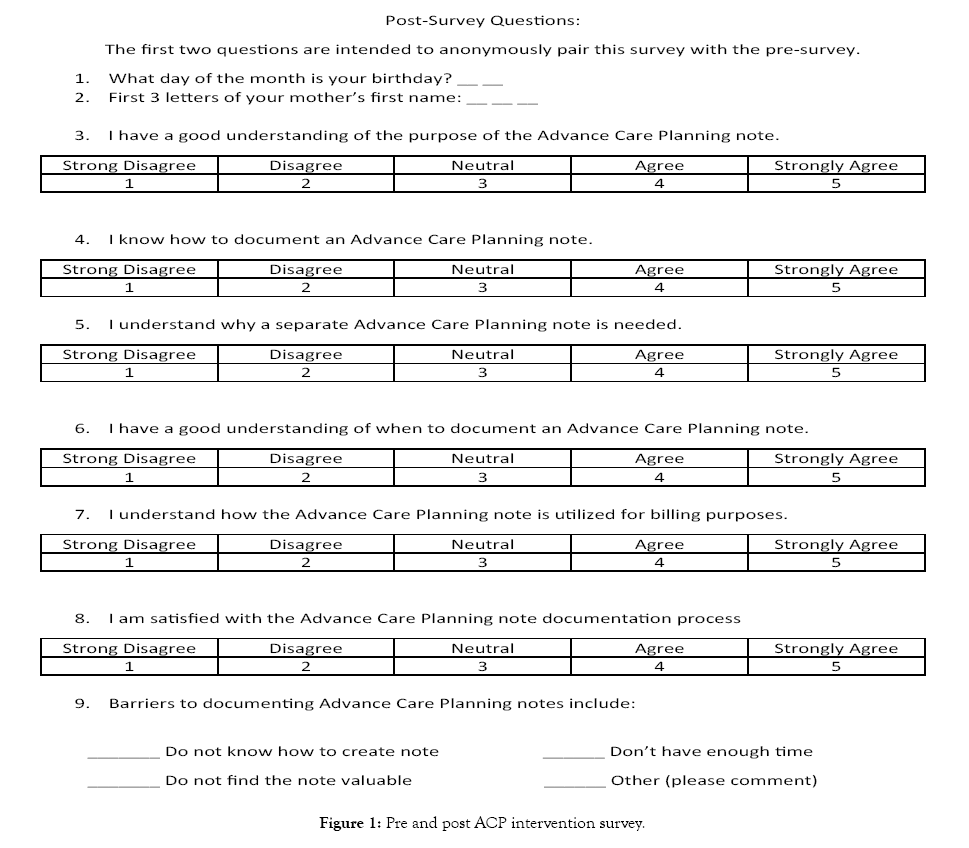

Measurement

A pre-intervention survey was developed and administered to the NP/PA SNF group prior to the one-hour ACP education session as demonstrated in Figure 1. The first two questions of the survey were used to anonymously pair the survey with the post-intervention survey. Questions two through eight of the survey used a fivepoint Likert scale to assess satisfaction and knowledge about the ACP process. The scale was divided into five groups: (1) strongly disagree (2) disagree (3) neutral (4) agree, and (5) strongly agree. Question seven was an open-ended question seeking information regarding the barriers in the ACP note completion process. The post-intervention survey was administered directly following the one-hour education session using the same questions as the preintervention survey to ensure quality and adequacy [19].

Figure 1: Pre and post ACP intervention survey.

The My Reports feature in the electronic medical record was utilized to collect the number of ACP notes completed during the 12-week pre-intervention (June 24, 2018 to September 9, 2018) and post-intervention period (September 10, 2018 to December 3, 2018). The data was extracted by selecting the date range, note type, and author. Once data was extracted, each note was individually examined by the DNP student to determine SNF location for proper data collection.

Phone calls to each of the 13 SNFs were placed by the DNP student to obtain pre and post-intervention census and admission numbers from each facility. An excel data spreadsheet was utilized to store census and admission values for each facility pre and postintervention.

Stakeholder support and sustainability

The primary stakeholders involved in the project were the NP/ PA providers, the SNF physician group, and the 13 Southeastern Minnesota SNFs. The support from the NP/PA providers allowed for a successful one-hour education session to be administered about the ACP process with pre and post-intervention surveys being completed during the education session. With the continued support from all stakeholders, if the ACP note completion process was shown to be effective, further clarity and education for all SNF providers to follow the CIM ACP process model would occur. If not, further evaluation through plan, does, study, and act cycles would be necessary to continue to fine-tune the process.

Barriers

There was one main barrier identified during the project and that was the lack of clarity of the CIM ACP process model time frame. The expectation of the process model was for the physician to complete the ACP note within 30 days of admission to the SNF. The rate of completion was variable based on the physician’s interpretation of the CIM ACP process model. The CIM ACP process model offers recommendations to complete within 30 days of admission to the SNF, update yearly, and/or if a patient has a change in medical condition or status.

Ethics and human subjects’ protection

Before commencement of the QI project, Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the organization the project was to be conducted was obtained and then submitted to IRB at the DNP students University. The project was classified as a QI project that used pre and post surveys and all data was deidentified. To ensure protection of data throughout the project, a secure folder on a password protected computer drive on the organization’s server was maintained. Only the project mentor and DNP student had access to the locked drive. With this information provided, the QI project was eligible for category 2 exempt status because there was no risk for human subjects [20]. After completion of the organization IRB approval, all information was submitted to the DNP student’s university prior to starting the QI project.

Budget

The projected budget for the pilot project was set at 20$ for survey supplies. After creation of the five-point Likert scale pre and postintervention survey, it was estimated that approximately less than 5$ was spent on paper and ink. Also, no monetary compensation was offered to NPs and PA for completing the surveys as outlined by the healthcare organizations policies.

Results

All 10 pre and post-education surveys were completed by the NP/ PA providers. Demographic data of participants who completed the ACP education session are displayed in Table 1. Ten respondents listed professions as NP (90%) and PA (10%), with majority being female (90%).

| Demographics | n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender |

Male | 1 (10) |

| Female | 9 (90) | |

| Provider role |

Nurse Practitioner (NP) | 9 (90) |

| Physician’s Assistant (PA) | 1 (10) | |

Table 1: Demographics of survey participants.

Since the sample size was small with a total of 10 participants, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test and mean value score were calculated for each survey question. On all six questions, a general increase in mean value was demonstrated. Question two, seven and eight demonstrated the greatest increase in mean value score of (0.7, 1.2, and 0.9) respectively. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test elicited significant change in knowledge (p=0.037), understanding of ACP note billing (p ≤ 0.001), and satisfaction with ACP note documentation (p=0.004). All other questions did not elicit a change as presented in Table 2.

| Survey Questions | Pre-education M (N=10) | Post-education M (N=10) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q3. I have a good understanding of the purpose of the Advance Care Planning note. | 4.5 | 4.5 | NS |

| Q4. I know how to document an Advance Care Planning note. | 3.7 | 4.4 | 0.037 |

| Q5. I understand why a separate Advance Care Planning Note is needed. | 4.3 | 4.5 | NS |

| Q6. I have a good understanding of when to document an Advance Care Planning note. | 4.1 | 4.5 | 0.037 |

| Q7. I understand how the Advance Care Planning note is utilized for billing purposes. | 3.1 | 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Q8. I am satisfied with the Advance Care Planning note documentation process. | 3.3 | 4.2 | 0.004 |

| Q9. Barriers to documenting Advance Care Planning notes | •Duplicate work •Haven’t created an ACP note ever •Don’t always think about putting in a separate note |

•Too much work to create the note •I will plan to start doing a separate note now that I know how to |

Note: M= Mean Value Score; NS= Not Significant; ACP= Advance Care Planning.

Table 2: Mean of survey items.

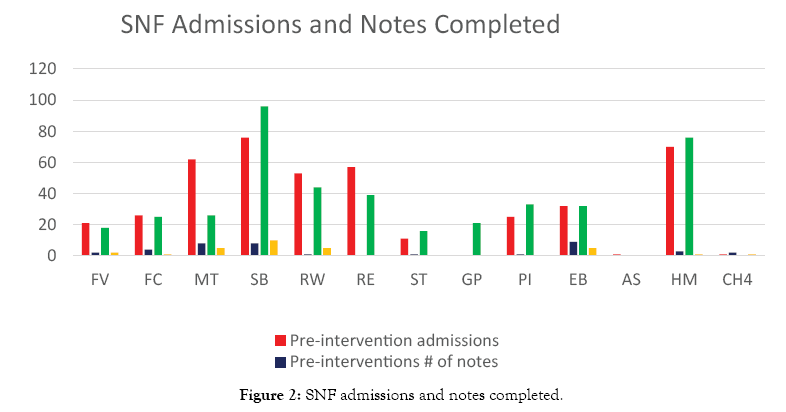

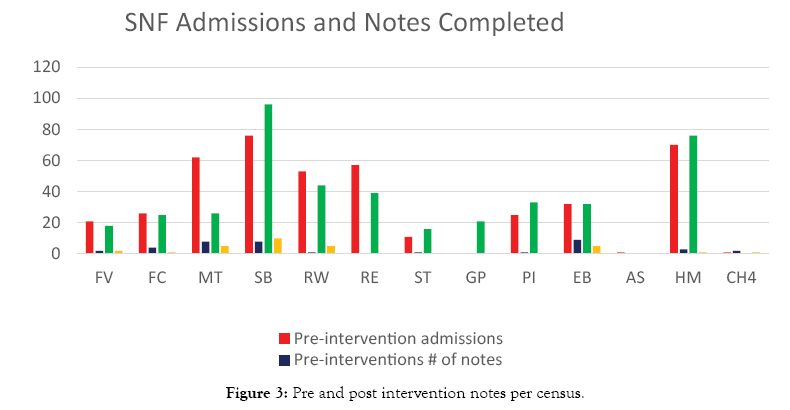

Question seven of the survey was an open-ended question that asked participants to list barriers to documenting the ACP note. Although less than half of the participants listed a response, valuable information was obtained. In the pre-intervention surveys responses, it was noted that it is a duplication of work, I have never completed an ACP note and I don’t always think about entering a separate ACP note. In the post-intervention responses, participants noted that it is too much work to create the separate note and I will plan to make changes to my practice and document a separate note now that I know how to. During the pre-intervention stage, 39 ACP notes were completed of the total of 435 SNF admissions; and post-intervention, 30 ACP notes were completed of the 426 admissions amongst the 13 SNFs as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: SNF admissions and notes completed.

In the pre-intervention stage, 8.97% of SNF admissions had an ACP note completed compared to 7.04% in the post intervention stage, indicating an almost 2% decrease in ACP notes completed per census in the post-intervention stage. As demonstrated in Figure 3 there was no significant correlation in total facility census and ACP note completion.

Figure 3: Pre and post intervention notes per census.

Discussion

The purpose of the QI project was to administer an ACP note educational session to increase knowledge and satisfaction for the NP/PA providers in the Southeastern Minnesota SNFs, as well as increasing the number of ACP notes completed in the same region. The ACP note education session demonstrated an improvement in knowledge and satisfaction amongst the NP/PA providers in the Southeastern Minnesota SNF group. Unfortunately, there was no increase in the number of ACP notes completed in the postintervention stage.

The ACP QI project confirmed that overall there was a general lack of knowledge about ACP amongst healthcare staff. Although the post-intervention demonstrated an increase in knowledge about the ACP note process, it would be valuable to create a more comprehensive education module to include areas of knowledge deficiency such as how to initiate the ACP conversation with the patient and family members [11]. This was similar to findings by Kermel-Schiffman & Werner that explained that initiatives need to be taken to create intervention programs and workshops to improve knowledge amongst healthcare providers [10].

Unfortunately, an increase in ACP notes post-education was not achieved. Jacobsen et al. conducted a QI project that included five interventions including provider education, ACP discussion during interdisciplinary team rounds, palliative care team involvement, selective identification of appropriate patients for discussion, and focused discussions with the patient and family members. The inclusion of the five interventions outlined by Jacobsen et al. would be beneficial in future expansion of the ACP QI project [16].

Although the project didn’t examine health utilization, in the future it would be useful to observe if the completion of the ACP note resulted in patients receiving care that was in concordance with their wishes; reducing pain and suffering as outlined by Clabots and Houben et al. [1,11]. As demonstrated through Martin et al., this outcome could also be measured by examining ACP note completion rates compared to hospitalization and the number of patients that died in the SNF following ACP note intervention [12].

Limitations

The QI project for ACP note completion was confronted with numerous limitations. First, the sample size for pre- and posteducation survey was small (N=10). With a larger sample size, more leverage may have been offered to the survey results. Another limitation was the short intervention window for ACP completion. If the intervention window was increased from 12-weeks to 16 to 24-weeks, there may have been a more robust collection of data. A third limitation was that the years of practice of NP and PA providers were not obtained through the surveys. In the future, inclusion of years of practice on the survey may help better understand the difference in ACP note completion rates in relation to the years of practice as a provider. Finally, the introduction of a new electronic medical record within the organization in the short few months prior to the intervention may have contributed to a lack of involvement and creation of ACP notes by participants.

Implications for practice

Results of this QI project suggest that greater education and training are needed for NP/PA providers in the Southeastern Minnesota SNF practice. To improve the education and training process, it would be necessary to receive recommendations for the NP/PA respondents about how best to improve on the education module.

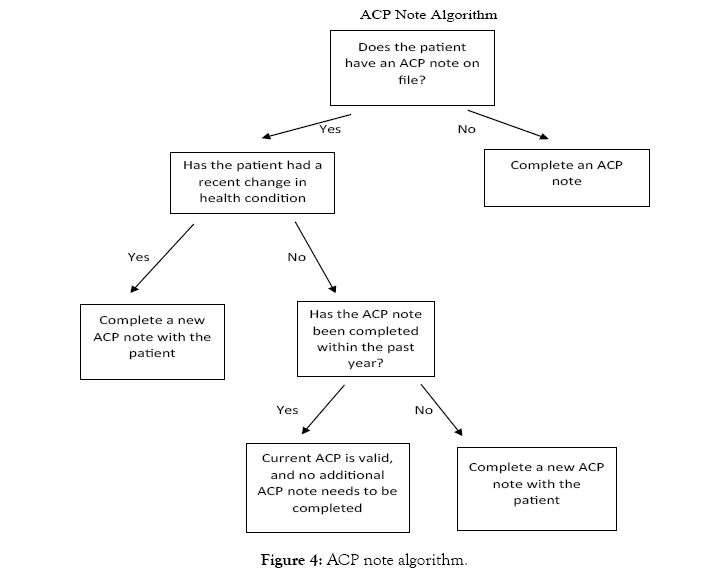

As indicated by Houben et al. and Hanson et al. and seen in the QI project was the lack of formal instruments and tools to measure satisfaction levels [11,17]. Future studies should focus on ACP satisfaction through the development of a validated tool. In the future, inclusion of an ACP note algorithm may be beneficial to provide clarity in ACP note completion amongst NP and PA providers (Figure 4). Additionally, further collaboration with the geriatricians in the SNF practice may be beneficial to offer additional buy-in and guidance for further expansion of the ACP process in the SNF setting. Based on the information obtained about ACP note completion, further interventions and research are needed to improve on ACP note completion in the SNF.

Figure 4: ACP note algorithm.

Conclusion

The QI project demonstrated that with ACP education an increase in knowledge and satisfaction occurred amongst NP and PA providers. Unfortunately, the project did not demonstrate an improvement in ACP note completion rates. Therefore, findings validate that continued improvements are needed to establish an effective ACP process in the SNF setting.

REFERENCES

- Clabots S. Strategies to help initiate and maintain the end-of-life discussion with patients and family members. Medsurg Nurs. 2012; 21(4):197-203.

- http://www.uptodate.com/contents/advance-care-planning-and-advance-directives

- Mueller PS, Hook CC, Fleming KC. Ethical issues in geriatrics: A guide for clinicians. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2004; 79(4): 554-562.

- McGough NH, Hauschildt B, Mollon D, Fields W. Nurses' knowledge and comfort levels using the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form in the progressive care unit. Geriatric Nursing. 2015; 36(1): 21-24.

- Hickman SE, Unroe KT, Ersek MT, Buente B, Nazir A, Sachs GA. An interim analysis of an advance care planning intervention in the nursing home setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016; 64(11): 2385-2392.

- https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/mm4246.pdf

- Hanson G. Clinical care provider expectations in the ECH outreach programs. (Community and Internal Medicine Report). Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic, USA. 2018.

- Rizzo VM, Engelhardt J, Tobin D, Penna RD, Feigenbaum P, Sisselman A, et al. Use of the stages of change transtheoretical model in end-of-life planning conversations. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(3): 267-271.

- Ernecoff NC, Keane CR, Albert SM. Health behavior change in advance care planning: An agent-based model. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1): 1-9.

- Kermel-Schiffman I, Werner P. Knowledge regarding advance care planning: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017; 73:133-142.

- Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Efficacy of advance care planning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014; 15(7): 477-489.

- Martin RS, Hayes B, Gregorevic K, Lim WK. The effects of advance care planning interventions on nursing home residents: A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016; 17(4): 284-293.

- Ahluwalia SC, Bekelman DB, Huynh AK, Prendergast TJ, Shreve S, Lorenz KA. Barriers and strategies to an iterative model of advance care planning communication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015; 32(8): 817-823.

- Weathers E, O'Caoimh R, Cornally N, Fitzgerald C, Kearns T, Coffey A, et al. Advance care planning: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials conducted with older adults. Maturitas. 2016; 91:101-109.

- Sinclair C, Auret KA, Evans SF, Williamson F, Dormer S, Wilkinson A, et al. Advance care planning uptake among patients with severe lung disease: A randomised patient preference trial of a nurse-led, facilitated advance care planning intervention. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(2): e013415

- Jacobsen J, Robinson E, Jackson VA, Meigs JB, Billings JA. Development of a cognitive model for advance care planning discussions: Results from a quality improvement initiative. J Palliat Med. 2011; 14(3): 331-336.

- Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, Lin FC, Rosemond C, Carey TS, et al. Effect of the goals of care intervention for advanced dementia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):24–31.

- Burson R, Moran K. The Doctor of Nursing Practice Scholarly Project: A framework for success. 2020.

- Bonnel W, Smith K. Proposal writing for nursing capstones and clinical projects. Springer. 2017.

- http://intranet.mayo.edu/charlie/irb/irbe/irb-wizards/

Citation: Copley M, Ingram C (2020) Nurse Practitioner-Led Education: Improving Advance Care Planning in the Skilled Nursing Facility. J Gerontol Geriatr Res 9: 507. doi: 10.35248/2167-7182.20.9.507

Copyright: © 2020 Copley M. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.