Indexed In

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- Publons

- Euro Pub

- Google Scholar

- Quality Open Access Market

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Mini Review - (2021) Volume 7, Issue 3

New Understanding of Psychosomatic Pain

Gosta Alfven1* and E Andersson22Department of Neuroscience, The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

Received: 02-Jul-2021 Published: 23-Jul-2021, DOI: 10.35248/2684-1320.21.7.154

Abstract

For better understanding and better care of psychosomatic pain valid and reliable diagnostic criteria is a prerequisite. The startle reflex is of importance for the understanding of the stress induced pain and the increased excitability in several muscles. The pattern of increased muscular tension and tenderness that can be found in these patients can be of valuable diagnostic support. Decreased oxytocin and increased cortisol is a sign of right brain dominance in stress and indicate psychosomatic pain. The omega-3 and omega-6 changes are an indication metabolic pain mechanism of interest to further study. Treatment is recommended to be guided by the knowledge here described.

Keywords

Psychosomatic pain; Therapeutic; Tender muscles; Algometer

Introduction

Psychosomatic pain is a pandemic disorder [1] affecting around a third of all children in the world. Prevention and therapeutic measures reaching many children are of major importance. An understanding of how body and brain is affected in recurrent psychosomatic pain is a prerequisite for the care of these children.

A strict diagnosis with defined criteria is needed to study a disorder in a valid and reliable way. That has hitherto been lacking in psychosomatic medicine. In this mini review we will present scientific findings in schoolchildren with recurrent psychosomatic pain diagnosed according to seven criteria: (i) Onset or aggravation of chronic negative stress at the time of onset of recurrent pain. (ii) Pain in parallel with chronic negative stress. (iii) Feeling better or pain‐free during periods of no or lessened chronic negative stress. (iv) Stress‐induced acute pain. (v) Most pain attacks are related to acute stress. (vi) The child is followed up for at least 1 year. (vii) Parents and child and doctor agree on diagnosis. At least six of the seven criteria have to be met for diagnosis and other disorders must be excluded.

The first five criteria concern validity and number six and seven concerns reliability. For reliable data person-centered approach with at several consultations and at a follow up after longer time is a needed. These criteria and approach have been applied in several studies, and a valid and reliable diagnosis for psychosomatic pain has been established [2-7].

With a strict diagnosis of recurrent psychosomatic pain, it has been meaningful and fruitful to investigate pathophysiological deviances characteristic for the disorder as well as the effect of treatment. Here we report results from studies of psychosomatic patients in children aged 6-18 years old.

Clinical Investigations

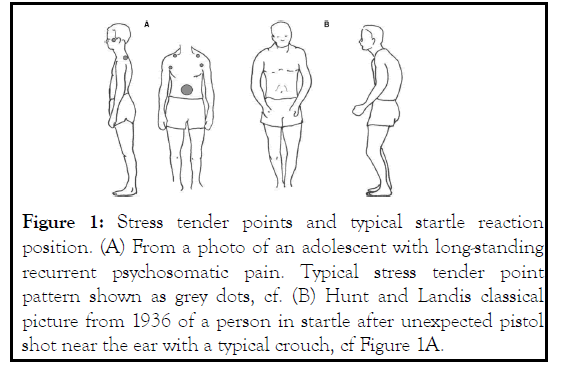

A pattern of tense and tender muscles located in muscles in psychosomatic pain children called Stress Tender Points (stress TP) pattern has been documented in several studies [3,4,7], see Figures 1 A and 1B. The recurrent psychosomatic pains such as headache, shoulder and abdominal pains are located at the same areas as the tender points [8].

Figure 1: Stress tender points and typical startle reaction position. (A) From a photo of an adolescent with long-standing recurrent psychosomatic pain. Typical stress tender point pattern shown as grey dots, cf. (B) Hunt and Landis classical picture from 1936 of a person in startle after unexpected pistol shot near the ear with a typical crouch, cf Figure 1A.

A lowered pain threshold at the tender points located at the tendo-muscular junction has been documented in an algometric study [9]. The Stress Tender Points pattern is a valuable tool in the diagnostic process for which experience and skill is needed. A pressure below approximately 125 kPa/cm2 eliciting tenderness is below the normal pain threshold for trapezius, pectoralis major and the abdomen is a sign of tender point [9]. The pressure can be calibrated by using an algometer [9].

Central pain sensitization is a common manifestation of longstanding psychosomatic pain, which increases the risk of developing pain spread and fibromyalgia [10]. An increased deep pain sensitivity in patients with persistent musculoskeletal pain has been shown, but not in regular recurrent pain patients or in acute pain [11]. A possibility for muscular psychosomatic pain is a lowered pain threshold via hyperalgesic priming elicited by stress [12].

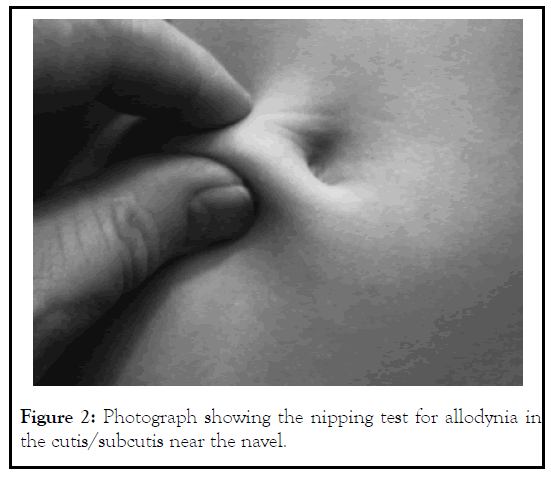

The nipping test is a standardized easy examination, for which no equipment is needed, to test for of allodynia in the cutis and sub cutis, a sign of sensitization. This test can be executed in less than a minute in the clinic practice. A low level of pressure, which would not normally elicit pain, is applied by nipping a layer of a small area of the cutis/subcutis between the thumb and index finger, with nails cut short; see Figure 2 . The nipping test has been validated for recurrent psychosomatic abdominal pain [4]. The subcutis is easily distinguished from the underlying muscles by the muscle fascia. The pressure applied is calibrated to be not higher than approximately 125 kPa/cm2 by using an algometer; a pressure below the normal pain threshold [9]. A pressure below pain threshold to be applied on the Nipple test can be found in a more practical way, but less scientific, by nipping a person without pain problems, i.e. the physician him/ herself.

Figure 2: Photograph showing the nipping test for allodynia in the cutis/subcutis near the navel.

An Epidemic Aspect

Two or several pains in one and the same person is common found among children with psychosomatic pain pointing at a common central origin [2,3,8,13]. One central mechanism for the recurrent psychosomatic pain is the startle reflex, which has been documented in an EMG-study, se next paragraph. In the exploration for the origin of pain, the result of multiple locations, related to muscle activated by the startle reflex, may support for an etiology of negative stress. The startle reaction affects muscles in the head, temporal region, neck, shoulder, abdomen and back.

An EMG study presented below supports the clinical hypothesis that the startle reflex is the pathophysiological mechanism behind the pattern of tense and tender muscle and the recurrent pain [2].

A case–control study, 21 matched healthy controls (CON) were compared to 19 children fulfilling the criteria for psychosomatic pain (PAIN). These children had a pain duration in mean of 37 months. All reported recurrent headache, 18 abdominal pain, five backache and three shoulder pain.

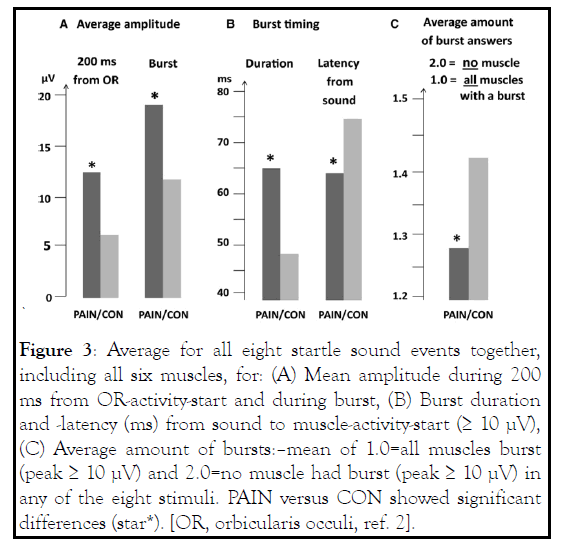

The acoustic startle reaction was elicited by a short signal of white noise of 105 dB via ear‐phones on eight occasions, and the response measured with electromyography (EMG). The muscles studied were the orbicularis oculi, temporal, trapezius, great pectoral near shoulder, abdominal wall near the umbilicus and the lumbar erector spine, that is sites for recurrent pain and stress tender points (Figures 2 and 3 ). All but one of the children had nine tender points, the exception having seven [9].

Figure 3: Average for all eight startle sound events together, including all six muscles, for: (A) Mean amplitude during 200 ms from OR-activity-start and during burst, (B) Burst duration and -latency (ms) from sound to muscle-activity-start (≥ 10 μV), (C) Average amount of bursts:–mean of 1.0=all muscles burst (peak ≥ 10 μV) and 2.0=no muscle had burst (peak ≥ 10 μV) in any of the eight stimuli. PAIN versus CON showed significant differences (star*). [OR, orbicularis occuli, ref. 2].

The Pain group showed significantly higher resting activity and higher acoustic startle response values (p<0,05), than the CON group, for all six muscles together regarding the mean amplitude in the initial 200 ms, and during the burst of activity (start ≥ 10 μV, end<10 μV), as well as longer burst duration and shorter burst latency (ms). These results are based on average for all eight startle sound events (ASR) together. For PAIN compared to CON, all separate muscles showed generally higher values of EMG amplitudes and burst durations as well as shorter latencies for the burst onset in all measures; with statistically significant differences or strong trends for several parameters and muscles [2].

Stress, increased muscle excitability, brain regions, pain and its relation to the startle reaction

An increased excitability in the α-motor neurons in the spinal cord can be due to supraspinal projections, and also by higher γ- motor activity and muscle-spindle input (Ia, II) and other afferents (III, IV) contributing to chronic hyper tonicity and pain [14-18]. Here, stimulus from by different local chemonociceptors may contribute (i.e. prostaglandins, bradykinin, arachidonic acid, lactic acid and potassium).

In chronic muscular pain, mental stressors can cause long-lasting hypersensitivity of nociceptors in reaction to a subsequent exposure to a low concentration of inflammatory mediators [12]. An investigation in rat revealed that unexpected short white noise at 105 dB, the same as utilized in our study [2], elicits hyperalgesic priming in the masseter muscle, known to be a part of the startle response. This will lower the pain threshold [19]. Via CNS feedback loops, such lowering of pain threshold can heighten the level of muscle activity and promote startle reactions.

Increased muscle excitability/tension seems to have a central role for the origin of recurrent pain of stress origin [2]. An important stress center in the brain, the amygdala, can be activated by mental stress from the anterior cingulate cortex, which is a neurobhiological center for behavior and motivation [20]. Thus, chronic stress may cause an increased neuromuscular excitability (both under resting conditions and during provocation tests such as the startle reflex) via altered descending neural activity from higher brain centers such as the anterior cingulate cortex and the amygdala [2, 20, 21].

Thus, the increased neuromuscular tension and excitability in children exposed to persistent stress with repeated pain can be caused by change of activity in a variety of brain regions. Prolonged stress has been described to make amygdala overactive and reduce the prefrontal cortex control over amygdala [22]. Also, the thalamo-amygdala and cortical regions can be involved in a dynamic interplay, which can be disturbed, seen similarly in different neuropsychiatric syndromes [23]. Consequently, various repetitive and prolonged stressful events have been described to be related with changes of activity, connectivity and size in various brain regions [8].

Hormonal Deviations

Oxytocin is significantly lowered according to two studies [6,24]. Here we report about 32 children 6-15 years old with psychosomatic abdominal pain had a mean oxytocin concentration of 30.5 pmol/L (95% confidence interval 24.6– 36.5), which was significantly lower than the control mean of 45.0 pmol/L (41.6–48.4), (p<0.0001)

Cortisol is significantly increased according to two studies with 17 respectively 35 children and when added together we found that the 52 children with psychosomatic pain had in mean a cortisol concentration in saliva 12.2 (3–42.7) n-mol/L and 296 controls in mean 8.5;(1.8–83.1) n-mol/L which was significant p<0.0001 (5). The decreased oxytocin and the increased cortisol are in accordance with right brain dominance in stress [20].

Antinociceptive fatty acid patterns differ in children with psychosomatic recurrent abdominal pain and healthy controls. This was shown in a study where 22 children 6-16 years were compared to a control group of 100 children [25]. Omega-3 was lower resulting to a higher ratio arachidonic acid to eicosapentaenoic acid despite lower arachidoic acid p<0.001 [25]. The deviations of the phospholipids omega-3 and omega-6 found in this study may be of importance for pain mechanisms in psychosomatic recurrent abdominal pain.

Treatment

We have done three treatment studies [4,26,27]. In the second study children had recurrent psychosomatic pain since 28.9 (3– 108) months and number of pain locations with a mean=2.5 (range 1–5). In this study clinical signs of activated startle reaction secondary to stress, the nine stress TP, as well as tender points fibromyalgia were studied at time zero and at follow up after one year. The children underwent treatment by a physiotherapist with psychosomatic education and experience. Before treatment stress TP was in mean 8,6 out of 9 and fibromyalgia TP was in mean 10,4 out of 18. At follow up 1 y 25 out of 44 were pain free with significant reduced tender points, for stress TP 2,8 and fibromyalgia TP 2,1.

Discussion

Our experience is that in severe psychosomatic state there is a sever risk of developing fibromyalgia. This indicates that early detection of recurrent psychosomatic pain is need to prevent fibromyalgia with serious consequences.

Treatment recommended for psychosomatic pain is based on a shared knowledge between the physician/caregiver and the patient including members of the family, of the relation between negative stress and psychosomatic symptoms. The mechanism how stress causes muscular tension, pain, hormonal deviation, and effects on emotional and cognitive processes are clarified. The stress tender pattern in the affected child is demonstrated, and the family gets a concrete picture and a better understanding of the stress reaction and how it affects the body.

How to get stress reduction and improved stress-handling are clarified. Guidance for a shift from right to left dominance in the bicameral brain with improved breathing, relaxation and release of startle tensions in muscles is given. A special trained physiotherapist or psychologist in psychosomatic treatment is often needed [27].

Conclusion

Observation Depression, attention deficit disorder and other neuro-psychiatric disorder often increase the susceptibility and the risk for stress and psychosomatic disorder. Our experience is that if treated as described in reference 4 and 26 the prognosis with treatment is good in most cases not affected by fibromyalgia.

REFERENCES

- Østerås B, Sigmundsson H, Haga M. Perceived stress and musculoskeletal pain are prevalent and significantly associated in adolescents: an epidemiological cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2015; 23(15): 1081.

- Alfvén G, Grillner S, Andersson E. Children with chronic stress‐induced recurrent muscle pain have enhanced startle reaction. Eur J Pain. 2017; 21: 1561–1570.

- Alfven G. One hundred cases of recurrent abdominal pain inchildren: Diagnostic procedures and criteria for a psychosomatic diagnosis. Acta Paediatr.2003; 92: 43–49.

- Alfven G. Recurrent pain, stress, tender points and fibromyalgia in childhood: an exploratory descriptive clinical study. Acta Paediatr.2012; 101: 283–291.

- Törnhage CJ, Alfvén G. Children with recurrent psychosomatic abdominal pain display increased morning salivary cortisol and high serum cortisol concentrations. Acta Paediatr. 2015; 104: 577–580.

- Alfvén G. Plasma oxytocin in children with recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.2004; 38: 513–517.

- Alfven G. Psychosomatic pain in children: A psychomuscular tension reaction? Eur J Pain. 1997; 1: 5–14.

- Alfven G, Grillner S, Andersson E. Review of childhood pain highlights the role of negative stress. Acta Paediatr. 2019; 108: 2148-2156.

- Alfvén, G. The covariation of common psychosomatic symptoms among children from socio-economically differing residential areas. An epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr.1993; 82: 481– 483.

- Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011; 152: 2–15.

- Gunnarsson HE, Grahn B, Agerström J. Increased deep pain sensitivity in persistent musculoskeletal pain but not in other musculoskeletal pain states. Scandinavian Journal of Pain. 2016; 13: 1–5.

- Reichling DB, Green PG, Levine JD. The fundamental unit of pain is the cell. Pain. 2013; 154.

- Alfvén G. The covariation of common psychosomatic symptoms among children from socio-economically differing residential areas. An epidemiological study. Acta Paediatr. 1993b; 82: 484– 487.

- Johansson H, Sojka P. Pathophysiological mechanism involved in genesis and spread of muscular tension in occupational muscle pain and in chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes: A hypotheses. Med Hypoth 1991; 35: 196–203.

- Djupsjöbacka M, Johansson H, Bergenheim M. Influence onthe gamma-muscle-spindle system from muscle afferents stimulated by increased intramuscular concentrations of arachidonic acid. Brain Res. 1994; 663: 293–302.

- Djupsjöbacka M, Johansson H, Bergenheim M, Wenngren BI. Influences on the gamma-muscle spindle system from muscle afferents stimulated by increased intramuscular concentrations of bradykinin and 5-HT. Neurosci Res. 1995a; 22: 325–333.

- Djupsjöbacka M, Johansson H, Bergenheim M, Sjölander P. Influences on the gamma-muscle-spindle system from contralateral muscle afferents stimulated by KCl and lactic acid. Neurosci Res. 1995b; 21: 301–309.

- Knutson GA. The role of the gamma-motor system in increasing muscle tone and muscle pain syndromes: A review of the Johansson/Sojka hypothesis. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000; 23: 564–572.

- Reichling DB, Levine JD, Green PG, Alvarez P, Gear RW, Mendoza D. Further validation of a model of fibromyalgia syndrome in the rat. J Pain. 2011; 12: 811–818.

- Craig AD. How do you feel. An interoceptive moment with your neurobiological self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University: Press Princeton and Oxford, 2015.

- LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ. Different projections of the central amygdala nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 1988; 8: 2517–29.

- Duval ER, Javanbakht A, Liberzon I. Neural circuits in anxiety and stress disorders: a focused review. Ther Clin Risk Manag.2015; 11: 115–126.

- Das P, Kemp AH, Liddell BJ, Brown KJ, Olivieri G, Peduto A, et al. Pathways for fear perception: modulation of amygdala activity by thalamo-cortical systems. NeuroImage. 2005; 26:141–148.

- Alfvén G, de la Torre B, Uvnäs-Moberg K. Depressed concentrations of oxytocin and cortisol in children with recurrent abdominal pain of non-organic origin. Acta Paediatr. 1994; 83: 1076-1080.

- Alfven G, Strandvik B. Antinociceptive fatty acid patterns differ in children with psychosomatic recurrent pain and healthy controls. Acta Paediatr. 2016; 105: 684–688.

- Alfvén G, Lindstrom A. A new method for the treatment of recurrent abdominal pain of prolonged negative stress origin. Acta Paediatr. 2007; 96: 76-81.

- Fors A, Wallbing U, Alfvén G, Kemani MK, Lundberg M, Wigert H, et al. Effects of a person-centred approach in a school setting of adolescents with chronic pain. The HOPE randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2020; 24:1598-1608.

Citation: Alfvén G, Andersson E (2021) New Understanding of Psychosomatic Pain. J Pain Manage Med. 7:154.

Copyright: © 2021 Alfvén G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited