Review Article - (2020) Volume 8, Issue 1

Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites mainly isolated from species of Solanaceae and Liliaceae families that occurs mostly as glycoalkaloids. α-chaconine, α-solanine, solamargine and solasonine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids commonly isolated from Solanum species. A number of investigations have demonstrated that steroidal glycoalkaloids exhibit a variety of biological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, among others. However, these are toxic to many organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals. To date, over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many Solanum species, all of these possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and have been divided into five structural types; solanidine, spirosolanes, solacongestidine, solanocapsine, and jurbidine. In this regard, the steroidal C27 solasodine type alkaloids are considered as significant target of synthetic derivatives and have been investigated for more than 10 years in order to obtain new physiologically active steroids. It is important to state that the wide range of biological activities and the low amount available from natural sources, make relevant to obtained these metabolites by synthetic pathway.

Steroidal glycoalkaloids; Synthetic derivatives; Solanum; Biological activity

Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites holding a basic cholestane skeleton and have mainly been isolated from around 300 species of the Solanaceae and Liliaceae families [1,2]. This type of components mostly occurs as glycoalkaloids, a nitrogencontaining steroidal glycosides found in members of the Solanum genus, including crop species, such as, potato (S. tuberosum), tomato (S. lycopersicum) and eggplants (S. melongena, S. macrocarpon and S. aethiopicum). These are usually found as paired structures sharing a common aglycon but holding two different sugar moieties, chacotriose or solatriose [3].

α-chaconine and α-solanine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids most commonly isolated from Solanum species (S. tuberosum, commonly known as potato), that contains solanidine as aglycon. Another pair of alkaloids frequentely found in Solanum species are solamargine and solasonine, which have a spirosolane basic skeleton with chacotriose or solatriose as carbohydrate moeity, respectively. Furthermore, Solanum species may also contain β-solamarine, which is the chacotriose glycoside of tomatidenol and α-solamarine whose aglycon is also tomatidenol, however, solatriose is the carbohydrate moiety. These glycoalkaloids confer Solanum plants resistance against pathogenic organisms and insects being the chacotriose containing glycoalkaloids the most active [4-7].

The large family of saponins has received considerable attention because of the diverse pharmaceutical properties [8]. Since ancient times, plant extract containing saponins have been used in traditional medicine and there has been a great interest for the study of the steroidal glycoalkaloids isolated from Solanum species [9,10]. Among these, chacotriose present in solamargine and chaconine, has caught the attention of researchers [11].

Chacotriose is a branched carbohydrate formed by one molecule of glucose and two molecules of rhamnose:α-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1 → 2)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 4))-D-glucopyranose. Solatriose is also a branched carbohydrate formed by galactose, rhamnose and glucose:α-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 3))-Dgalactopyranose. The structure of chacotriose and solatriose [12,13].

There are also oligosaccharide counterparts to chacotriose, in particular solatriose, 〈-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-[β-Dglucopyranosyl-( 1 → 3)]-β-D-galactopyranose [14-17]. However, glycosides-containing chacotriose are consistently more active than their solatriose-containing counterparts [16]. Dioscin, the diosgenyl-3-O-β-chacotrioside isolated from oriental vegetables and traditional medicinal plants, displayed promising in vitro antitumor activities [16-18].

Furthermore, some investigations have indicated that glycoalkaloids must have evolved in nature to protect plants against bacteria, fungi, insects, and animals. They are toxic to a wide range of organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals [19]. However, it has been reported that many of glycoalkaloids have important biological and pharmaceutical activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, anti-estrogen, among others [20-25]. Nevertheless, these compounds may cause toxicity if used over 2-5 mg/kg (body weight) since may promote systemic and gastrointestinal effects and also down-regulate acetylcholinesterase effect [26]. Glycoalkaloids might also disrupt cells by making a complex with sterol at cellular membranes [27]. Neurological signs and symptoms of toxicity due to glycoalkaloids include; weakness, depression, coma, convulsions, paralysis and mental confusion [28].

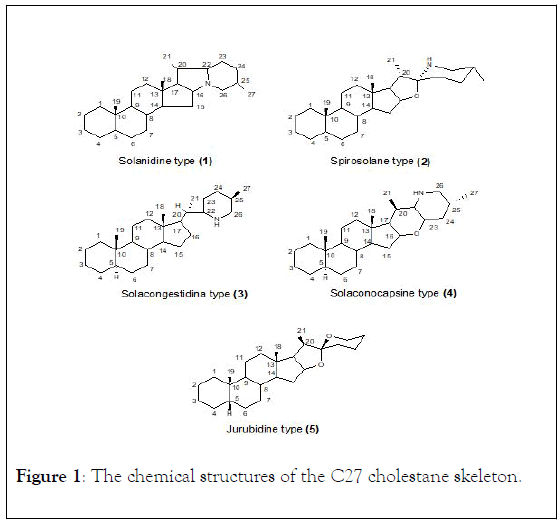

Solanaceae family has yielded several types of steroidal bases, and over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many species of Solanum and Lycopersicon [29-39]. All these alkaloids possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and may be divided into five structural types (Figure 1): Solanidine (1) Spirosolanes (2) Solacongestidine (3) Solanocapsine (4) and Jurbidine (5) [30].

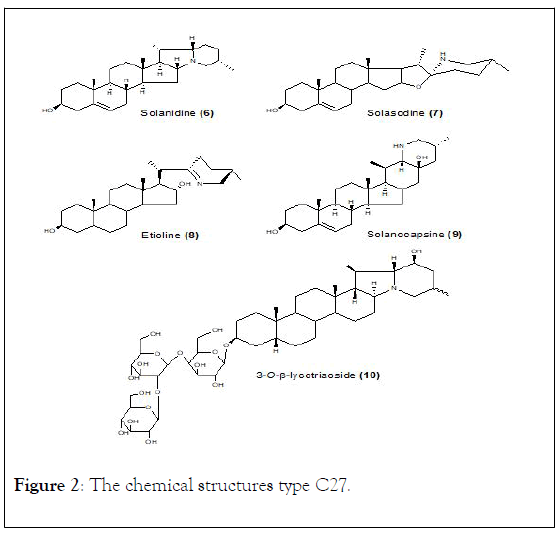

In Solanaceae family the steroidal C27 type alkaloids jervaratrum and cervaratrum have not been found yet, while solasodine (7) has remained as an important target of synthetic studies over the last 10 years. A number of solasodine derivatives (7) (Figure 2), such as N-cyano and A-nor-3-aza derivatives and degradative products, were prepared in order to obtain new physiologically active steroids.

Figure 1: The chemical structures of the C27 cholestane skeleton.

Figure 2: The chemical structures type C27.

Glyco-derivatives of solasodine, such as solaradixine, solashbanine, solaradine, robustine, and ravifoline, have also been isolated from species of Solanum genus [37,38]. In addition, over 50 members of the solacongestidine type steroidal alkaloids have also been obtained, mostly from Solanum and Veratrum species. A representative example is etioline (8), which was isolated from Solanum capsicastrum Link, S. spirale, S. havanense, Veratrum lobelianum, and V. grandiporum [39,40].

Leaves, roots, and stems of Solanum havanense Jacq. provided - solamarine and the glycoside etiolinine (8), while solanidine-type alkaloids (1) have been isolated mainly from Solanum species, however, these have also been found from species of the Liliaceae family specifically in Veratrum, Rhinopetalum, Fritillaria, and Notholiron genera. About 40 members of this class, including both alkamines (aglycone) and glycoalkaloids have been reported being solanidine (6) the most important member of this group [9,37,41,42].

Stems of S. lyratum have yielded a mixture of steroidal glycoalkaloids, including 3-O-β-lycotriaoside (10). Only a few members of solanocapsine type (4) alkaloids are known, and have been isolated from Solanum species. Solanocapsine (9) is an important member of this class, isolated from S. capsicastrum L. S. hendersonii Hort, and S. pseudocupsicon L. [43].

Form the roots of Taibyo Shinko No. 1 (a hybrid between Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. and L. hirsutum Humb. et Bonpl.), which is a tomato stock highly resistant to soil-borne pathogens, were isolated two solanocapsine-type alkaloids, 22,26- epi-imino-16β,23-epoxy-23α-ethoxy-5α,25αH-cholest-22-(N)- ene-3β,20α-diol and 22,26-epi-imino-16α,23-epoxy-5α, 22βH-cholestane-3β,23α-diol. Jurubidine-type (5) bases are a small group of Solanum alkaloids, from which jurubidine is the most representative example [44].

A number of investigations carried out with steroidal glycoalkaloids isolated from different Solanum species have demonstrated that these type of secondary metabolites have antifungal [45-51], trypanolytic, trypanocidal [52], larvicidal, molluscicide, acaricidal [53-56], hepatoprotective [57-59], antiulcerogenic [60], anti-seizure [61], cytoprotective [62], neuropharmacological [63], antioxidative [64,65], antimicrobial [66] and embryotoxic activities [67]; as well as exhibit significant anticancer effect. In addition, glycosides containing chacotriose are consistently more active than solatriose containing counterparts regarding antiviral [68-70] antiestrogen [71], antiinflammatory [72-74], mastitis [75], antitumour [76-82]; teratogenic [83,84] and antibacterial activities [85,86].

Despite the wide range of reported pharmacological studies, anticancer activity seems to be considered as high priority to researchers who stated that glycosides from Solanum plants, showed potent antitumor activity, specifically chacotriosyl steroids such as, 〈-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 4)-[ 〈-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1 → 2)]-β-D-glucopyranosyl, however, those compounds that contain an extra sugar on the side chain lack of activity [87,88]. The steroidal glycosides isolated from S. dulcamara, S. lyratum and S. nigrum, exhibit cytotoxicity towards human cancer cells and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) [89]. According to traditional medicine in China and Japan, the entire plant of Solanum nigrum is used to treat different types of cancer such as liver, lungs, urinary bladder, larynx, and carcinoma of vocal cords [90].

Anticancer phytochemicals present in Solanum nigrum include glycoproteins, polysaccharides, steroidal alkaloids and glycoalkaloids [91]. Among these solanine, solamargine, solasonine and solasodine are the most common glycoalkaloids observed [92,93]. Solasodine exhibits potent antitumour activity both in vitro and in vivo [94,95], however, the solasodine glycosides are regularly more cytotoxic against a variety of tumour cell lines when compared with its aglycone [96,97]. Glycoalkaloid 〈-solamargine isolated from Solanum incanum, a chinesse herb, triggers gene expression of human TNF 1 that may lead to cell apoptosis. Similarly, the anticarcinogenic action of solamargine on human hepatoma cells (Hep3B) has proved to induce cell death by apoptosis. Furthermore, 〈-solasonine from S. crinitum and S. jabrense has demonstrated cytotoxic activity against erlich carcinoma and human K562 leukemia cells as well as, chaconine, solanine, tomatine and their derivatives inhibit the growth of human colon (HT29) and liver (HepG2) cancer cells [98].

Glycoalkaloids solamargine and solasonine, isolated from Solanum sodomaeum have shown activity against malignant human tumors [99]. Tomatidine is able to reduce the resistance of cancer cells to drugs [100]. α-solamargine and α-solasonine, isolated from S. melongena, S. macrocarpon and S. aethiopicum have potential to treat different types of cancers, such as gastric cancer, leukemia [101], liver cancer, lung cancer, osteosarcoma [102] and basal cell carcinoma [103]. In addition, antiparasitic activity on Leishmania mexicana [104], and Trypanosoma cruzi they has been reported in the literature for these type of components [105].

It is also important to mention the applications of these compounds in traditional medicine. In Australia a topical preparation that contains a mixture of solasodine glycosides (BEC) is used to treat cutaneous solar keratosis [106,107]. In Venezuela the juice obtained by expression of Solanum americanum Miller fruits are used to treat skin injuries caused by Herpes zoster, Herpes simplex and Herpes genitalis. The main steroidal glycoalkaloids found in the fruits of this species are 〈- solamargine and 〈-solasonine [108,109]. Leaves of Solanum nigrum is applied topically for the treatment of sores, carbuncles, swelling and injuries [110]. Likewise, it is used to treat stomachache, jaundice, liver problems, toothache and many skin diseases [111]. 〈-chaconine, the glycoside of solanidine with chacotriose, is highly effective against Herpes simplex virus, whereas the corresponding aglycone is inactive. Despite the beneficial effects of glycoalkaloids these may be toxic to humans and might even cause death at high concentrations (3-5 mg/kg body mass) [112]. Several investigations have revealed that α- solanine, α-chaconine, as well as solanidine and other Solanum steroidal alkaloids are responsible for the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and may lead to central nervous system damage [113].

According to literature consulted there are a number of investigations regarding the synthetic derivatives of Solanum alkaloids. In addition, the biological activity and the low amount available from natural sources, make relevant to obtained these metabolites by synthetic pathway. Thus, many researchers have carried out diverse synthetic pathways to obtain chacotriose and its analogues [114-118].

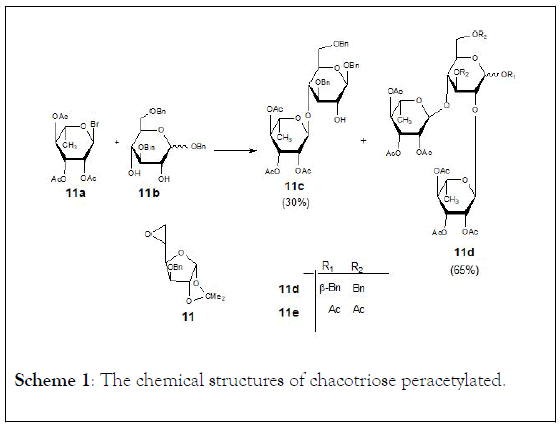

They synthesized chacotriose peracetylated from D-glucose as starting unit. The strategy adopted was to partially protect the glucose molecule leaving the 2-and 4-hydroxyl groups available for glycosidic bond formation with two L-rhamnopyranose units. The final reaction of peracetylated chacotriose provided 5,6- anhydro-3-O-benzyl-1,2-O-isopropylidene-α-D-glucofuranose (11). On the other hand, L-Rhamnose was first peracetylated with Ac2O–C5H5N and treated with 4.5 equivalents of HBr (33% in glacial acetic acid) to obtain 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-α-Lrhamnopyranosyl bromide (11a). Compound (11b) was mixed with four equivalents of (11a) in dry CH2Cl2 at 0°C, in the presence of tetramethylurea and silver triflate to give benzyl 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 4)-3,6-di-O-benzyl- β-D-glucopyranoside (11c) (30%) and benzyl 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl- α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-[(2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-α-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1 → 4)]-3,6-di-O-benzyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (11d) (65%). Compound (11d) was subjected to catalytic hydrogenolysis to remove the benzyl protecting groups and subsequently acetylated to obtain the desired peracetylated chacotriose (11e) in 24% yield (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1: The chemical structures of chacotriose peracetylated.

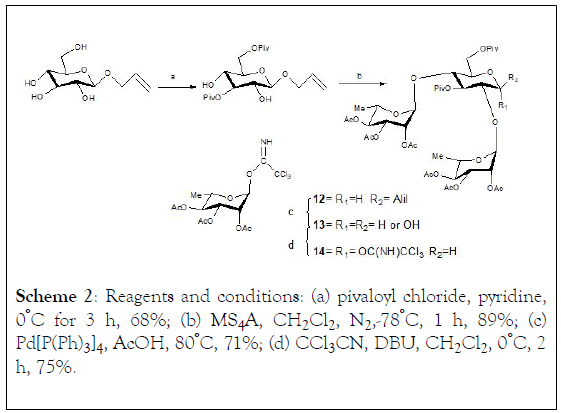

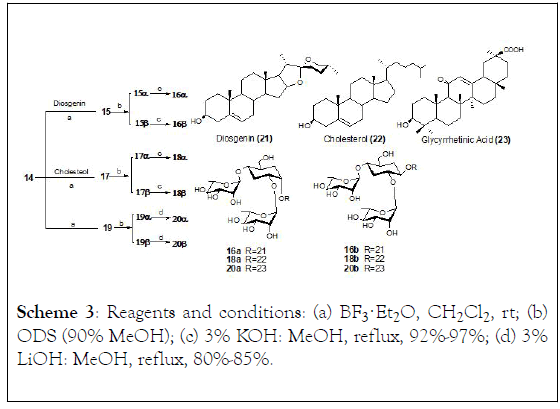

They synthesized 〈-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1.4)-[ 〈-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1.2)]- 〈-D-glucopyranosyl (chacotriosyl) trichloroacetimidate (6) from allyl glucoside as initial molecule to obtained (6), achieving 32% overall yield, even though the 〈- glycosides were predominant over β-glycosides in the oligoglycosylation. According to cytotoxic assays only 16β isomer proved to be active, thus, both the β-chacotrioside and the steroidal aglycone moiety are considered relevant for the cytotoxic activity (Schemes 2 and 3).

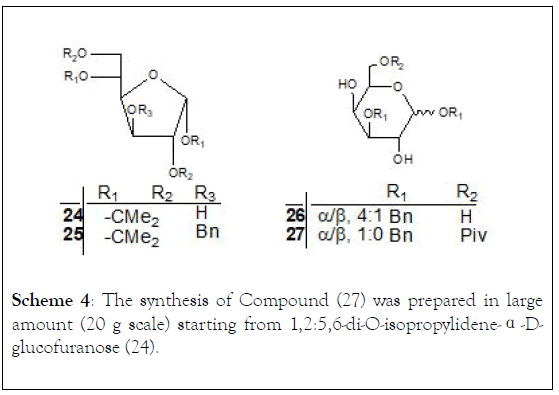

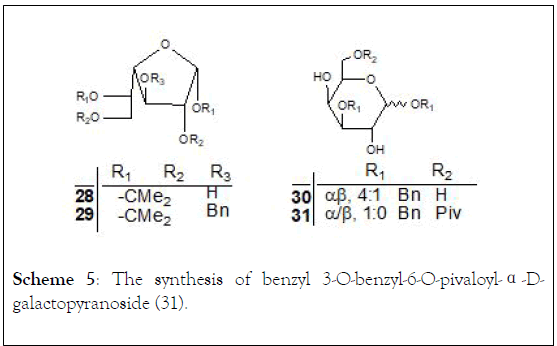

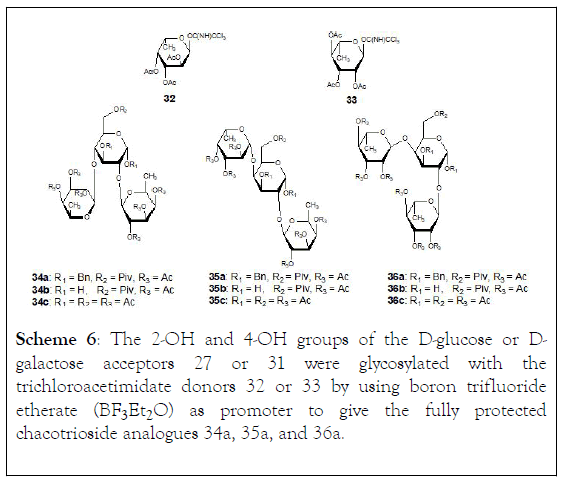

The synthesis of three chacotriose analogues, β-Lfucopyranosyl-( 1 → 2)-[β-L-fucopyranosyl-(1 → 4)]-Dglucopyranose, β-L-fucopyranosyl-(1→2)-[β-L-fucopyranosyl-(1 →4)]-D-galactopyranose, and 〈-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)-[〈- L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)]-〈-D-galactopyranose (Schemes 4-6) [11].

Scheme 2: Reagents and conditions: (a) pivaloyl chloride, pyridine, 0°C for 3 h, 68%; (b) MS4A, CH2Cl2 , N2,-78°C, 1 h, 89%; (c) Pd[P(Ph)3]4, AcOH, 80°C, 71%; (d) CCl3CN , DBU, CH2Cl2 , 0°C, 2 h, 75%.

Scheme 3: Reagents and conditions: (a) BF3·Et2O , rt; (b) ODS (90% MeOH); (c) 3% KOH: MeOH, reflux, 92%-97%; (d) 3% LiOH: MeOH, reflux, 80%-85%.

Scheme 4: The synthesis of Compound (27) was prepared in large amount (20 g scale) starting from 1,2:5,6-di-O-isopropylidene-α-Dglucofuranose (24).

Scheme 5: The synthesis of benzyl 3-O-benzyl-6-O-pivaloyl-α-Dgalactopyranoside (31).

Scheme 6: The 2-OH and 4-OH groups of the D-glucose or Dgalactose acceptors 27 or 31 were glycosylated with the trichloroacetimidate donors 32 or 33 by using boron trifluoride etherate (BF3·Et2O) as promoter to give the fully protected chacotrioside analogues 34a, 35a, and 36a.

Compound (27) was readily prepared in large amount starting from 1,2:5,6-di-O-isopropylidene-α-D-glucofuranose (24). Compound (25) was prepared by condensing (24) with benzyl bromide in 83% yield. Removing the isopropylidene protection followed by selective protection of the anomeric hydroxyl with benzyl alcohol in the presence of acetyl chloride afforded compound (26), (Scheme 4).

By the same method, we also prepared the galactosylated acceptor (31), starting from 1,2:5,6-di-O-isopropylidene-α-Dgalactofuranose (28). Removing the isopropylidene protection of (29) with 3:2 HOAc–H2O followed by selective protection of the anomeric hydroxyl with benzyl alcohol in the presence of acetyl chloride afforded compound (30) (65% yield). The anomeric mixture (30α/30β) (α=β, 4:1) was separated by conventional work up: acetylation following by deacetylation. Position 6 of (30α) was selectively protected with pivaloyl chloride in pyridine to give benzyl 3-O-benzyl-6-O-pivaloyl-α-Dgalactopyranoside (31) in 76% yield, (Scheme 5).

The 2-OH and 4-OH groups of the D-glucose or D-galactose acceptors (27) or (31) were glycosylated with the trichloroacetimidate donors (32) or (33) by using boron trifluoride etherate (BF3ÆEt2O) as promoter to give the fully protected chacotrioside analogues (34a, 35a, and 36a), (Scheme 6).

Trisaccharides (34a, 35a, and 36a) were then peracetylated. The protected trisaccharides were treated with hydrogen in the presence of Pd/C (10%) to give (34b-36b) and, then with NaOH to remove the pivaloyl and acetyl groups, and were subsequently acetylated to obtain the desired peracetylated chacotriose analogues (34c, 35c, and 36c), (Scheme 6).

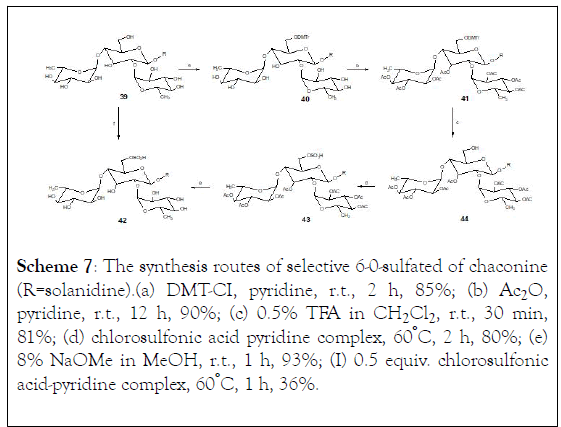

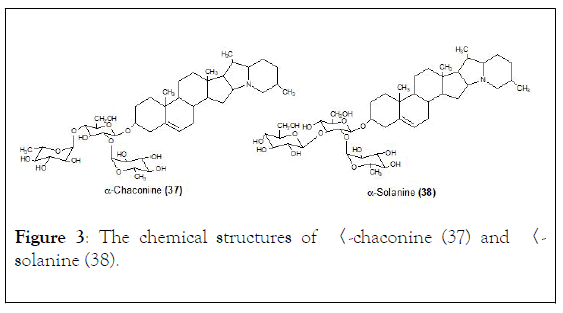

The isolation of two natural glycoalkaloids, 〈-chaconine (37) and 〈-solanine (38), isolated from potato stems and leaves (Solanum tuberosum L.) (Figure 3) [118].

In order to obtain the synthetic analogues of these natural glycoalkaloids, D-galactose and L-fucose were used as starting molecules. The 6-hydroxyl groups of sugar moiety in chaconine and solanine were protected with 4,4'-dimethoxytrityl (DMT) while the additional hydroxyl groups were acetylated. The protective group DMT was removed by using 0.5% TFA in dichloromethane. The free 6-hydroxyl groups were treated with chlorosulfonic acid in pyridine to yield 6-0-sulfated derivatives. Finally, the acetyl groups were removed to obtain sulfated chaconine and sulfated solanine (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7: The synthesis routes of selective 6-0-sulfated of chaconine (R=solanidine).(a) DMT-CI, pyridine, r.t., 2 h, 85%; (b) Ac2O, pyridine, r.t., 12 h, 90%; (c) 0.5% TFA in CH2Cl2 , r.t., 30 min, 81%; (d) chlorosulfonic acid pyridine complex, 60°C, 2 h, 80%; (e) 8% NaOMe in MeOH, r.t., 1 h, 93%; (I) 0.5 equiv. chlorosulfonic acid-pyridine complex, 60°C, 1 h, 36%.

Figure 3: The chemical structures of 〈-chaconine (37) and 〈- solanine (38).

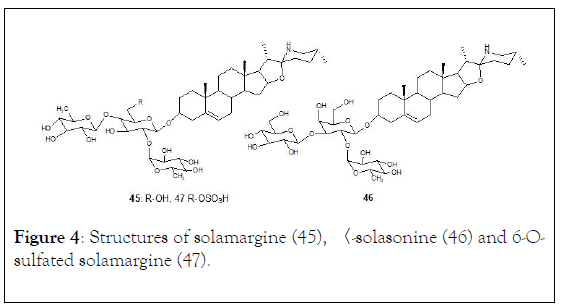

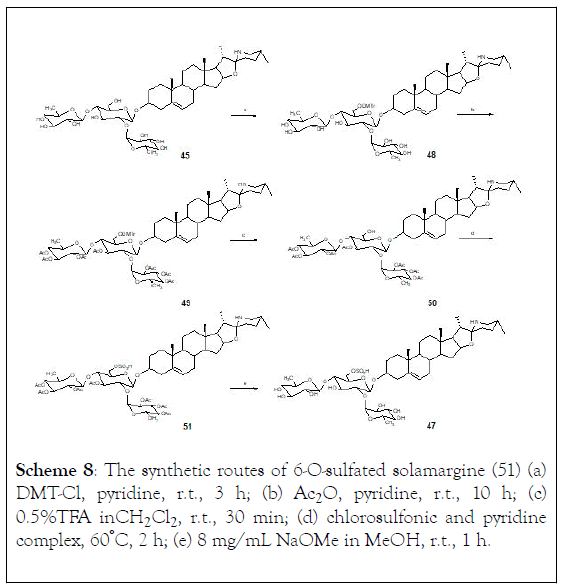

The structures of two glycoalkaloids 〈-solamargine (45) and 〈- solasonine (46) are shown in (Figure 4) [119].

The possible effect of the sugar moiety present in glycoalkaloids against cancer cells. In this regard, 6-O-sulfated solamargine and catalyzed hydrolytic products of α-solamargine and α- solasonine were prepared. The sulfation at 6-O of solamargine was carried out by five steps. First stage was to selectively protect the 6-OH group with DMT-Cl, followed by the acetylation of secondary hydroxyl groups on the sugar ring. Once the protective group on the 6-OH was removed, a sulfonation was carried out to obtain the sulfate derivative. Finally, the acetyl groups on the sugar molecule were removed to yield 6-O-sulfated solamargine (51), (Scheme 8) [119].

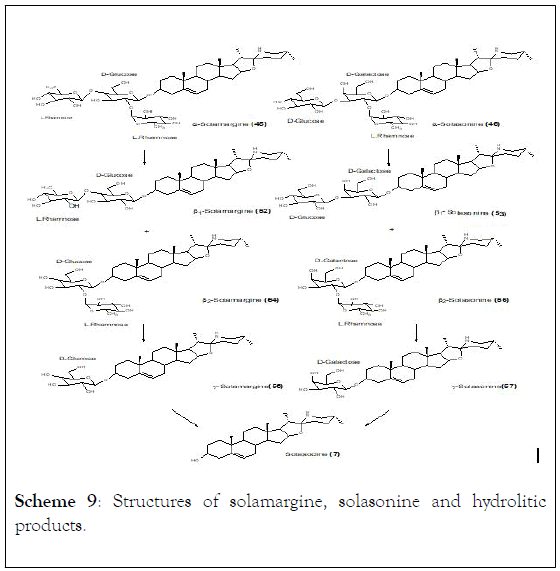

The partial acidic hydrolysis of α-solamargine and α- solasonine lead to formation of disaccharides β1 and β2- solamargine as well as β1 and β2-solasonine. Similarly, monosaccharides ©-solamargine, ©-solasonine and aglycon solasodine were also obtained (Scheme 9). Results demonstrated that ©-solamargine and aglycon solasodine were the main products observed while ©-solasonine was achieved in low yield and β-solasonine could not be successfully obtained.

Figure 4: Structures of solamargine (45), 〈-solasonine (46) and 6-Osulfated solamargine (47).

Scheme 8: The synthetic routes of 6-O-sulfated solamargine (51) (a) DMT-Cl, pyridine, r.t., 3 h; (b) Ac2O, pyridine, r.t., 10 h; (c) 0.5%TFA in CH2Cl2 , r.t., 30 min; (d) chlorosulfonic and pyridine complex, 60°C, 2 h; (e) 8 mg/mL NaOMe in MeOH, r.t., 1 h.

Scheme 9: Structures of solamargine, solasonine and hydrolitic products.

Glycoalkaloids have drawn scientific attention due to the significance of their biological activities. Some studies have revealed that differences in glycoalkaloids structure including the type and number of sugar moieties attached by a glycosidic bond at C-3 may be related to several biological activities. A study carried out by Li et al in 2007, showed the antiproliferative activities against HCT-8 cancer cells of 〈-solamargine, 〈- solasonine and their derivatives, including 6-0 sulfated solamargine and partial acidic hydrolyzed products. Results showed that 〈-solamargine and 〈-solasonine exhibit strong cytotoxic activity with IC50 values of 10.63 and 11.97 mol/L, respectively, whereas their derivatives proved to be less active. Authors concluded that sugar chains present in glycoalkaloids molecules might play an important role in this activity.

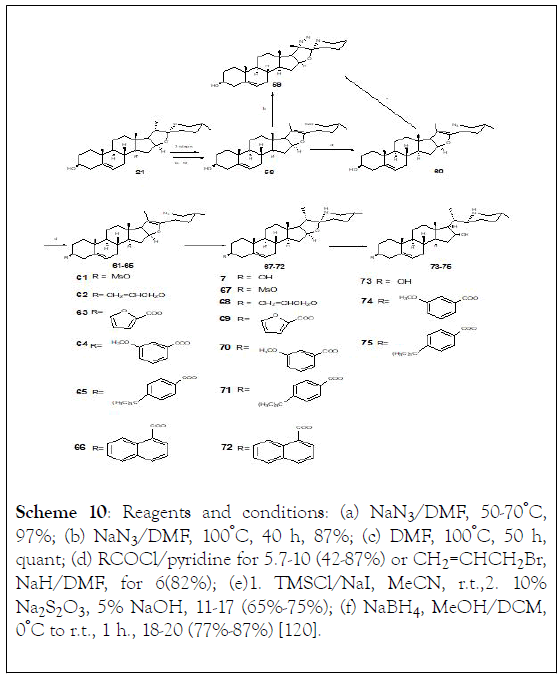

The synthesis of eight solasodine derivatives and their effect on prostate cancer cell proliferation was assessed in vitro. Significant improvement in antiproliferative activity was achieved among some of the synthetic analogs. In particular, (74) exhibited the most potent inhibitory effect against the proliferation of PC-3 cell line (IC50: 3.91 mmol/L). The cellular activity of (7,59,67-69), and (71-75) compounds (purity above 98%), was evaluated in a prostate gland adenocarcinoma cell line (PC-3). Solasodine (7) also showed inhibitory effect on the proliferation of PC-3 cell line with IC50 value of 25 mmol/L. Esterization and etherisation of solasodine at C-3 position (67-72), except for (72) (1-naphthoyl), did not enhance the inhibitory activity. In comparison to solasodine, analogs (59) and (74) significantly improved the cytotoxicity on PC-3 cell line. However, analogs (73) (3β-hydroxyl) and (75) (3β-p-tertbutylbenzoyl) exhibited a rather low activity suggesting that substitution at C-3 might be related to the in vitro anticancer activity observed (Scheme 10) [120].

Scheme 10: Reagents and conditions: (a) NaN3 /DMF, 50-70°C, 97%; (b) NaN3 /DMF, 100°C, 40 h, 87%; (c) DMF, 100°C, 50 h, quant; (d) RCOCl/pyridine for 5.7-10 (42-87%) or CH2=CHCH2 Br, NaH/DMF, for 6(82%); (e)1. TMSCl/NaI, MeCN, r.t.,2. 10% Na2S2O3, 5% NaOH, 11-17 (65%-75%); (f) NaBH4, MeOH/DCM, 0°C to r.t., 1 h., 18-20 (77%-87%) [120].

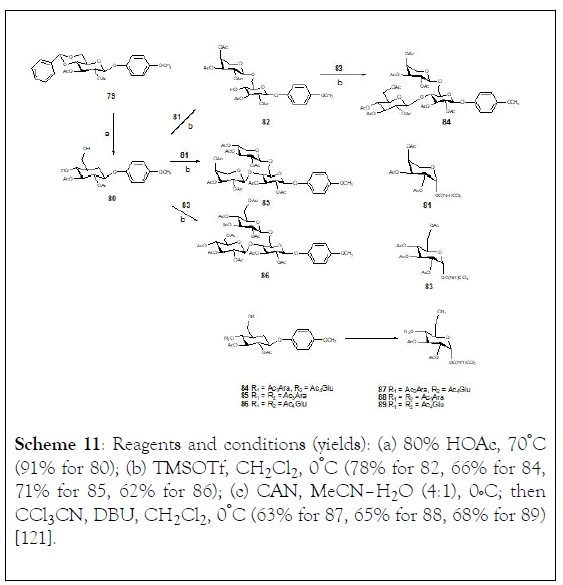

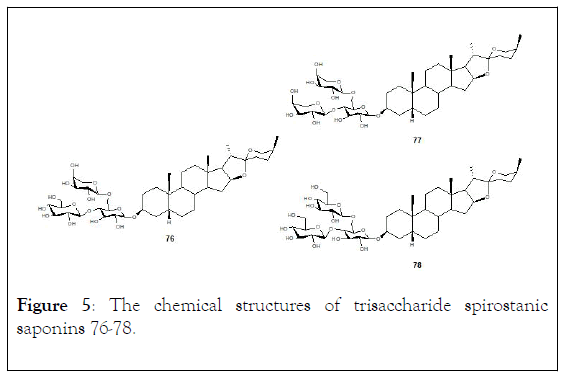

The synthesis of β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 4)-[ 〈-Larabinopyranosyl-( 1→6)]-β-D-glucopyranoside (sarsasapogenin), a trisaccharide spirostanic saponin (76, Figure 5), through a direct transglycosylation strategy. In addition, two trisaccharide saponin derivatives (77) and (78), which contain a structurally modified trisaccharide unit were also obtained as shown in Scheme 11 [121].

Scheme 11: Reagents and conditions (yields): (a) 80% HOAc, 70°C (91% for 80); (b) TMSOTf, CH2Cl2 , 0°C (78% for 82, 66% for 84, 71% for 85, 62% for 86); (c) CAN, MeCN–H2O (4:1), 0°C; then CCl3CN, DBU, CH2Cl2 , 0°C (63% for 87, 65% for 88, 68% for 89) [121].

Figure 5: The chemical structures of trisaccharide spirostanic saponins 76-78.

To complete the synthesis of molecules (76-78), a direct transglycosylation strategy using trisaccharide trichloroacetimidates as glycosyl donors was assessed. The first step of the synthesis was the preparation of 4,6-dibrached trisaccharide (Scheme 11). Acidic cleavage of the benzylidene group of 4-methoxyphenyl 2,3-di-O-acetyl-4,6-di-O-benzylidene- β-D-glucopyranoside (79) with 80% acetic acid at 70°C afforded 4,6-diol, 80 with 91% yield. Regioselective glycosylation of compound (80) and 2,3,4-tri-O-acetyl-β-L arabinpyranosyl trichloroacetimidate (81) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 at 0ºC under the promotion of trimethylsilyl triflate (TMSOTf) gave the α-(1→ 6)-linked disaccharide (82) in 78% yield. Coupling of disaccharide (82) and 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-D-glucopyranosyl trichloroacetimidate (83) in CH2Cl2 with TMSOTf as a catalyst lead to formation of trisaccharide (84). In addition, direct condensation of compound (80) along with arabinosyl donor (81) in dry CH2Cl2 in the presence of TMSOTf gave 4,6- diarabinosylated glucopyranoside (85) with 71% yield. Similarly, the trisaccharide (86) was obtained from 4,6-glucosyaltion (80) and glucosyl donor (83) catalyzed by TMSOTf under standard glycosylation condition. Furthermore, cerium ammonium nitrate (CAN)-promoted cleavage (86) of the anomeric 4- methoxyphenyl group of trisaccharides (84-86) in a 4:1 MeCN– H2O solvent system, followed by trichloroacetimidate formation (87) with trichloroacetonitrile (Cl3CCN) and 1,8-diazabicyclo [5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU), afforded the trisaccharide donors (87-89), (Scheme 11).

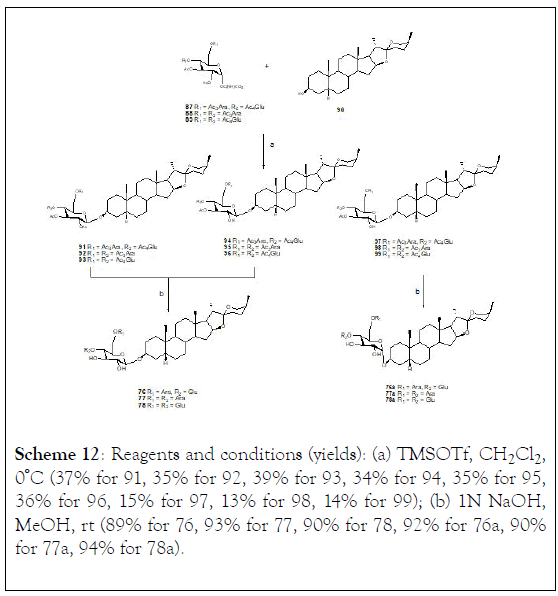

Direct condensation of the trisaccharide donors (87-89) and sarsasapogenin aglycon (90) in the presence of TMSOTf in CH2Cl2 at 0°C generated the fully protected trisaccharide saponins (91-93) (Scheme 12). The trisaccharide products (91-93) were obtained together with C-2 deacetylated trisaccharide products (94-96) and α-isomers of trisaccharide products (97-99). Finally, deacetylation of the trisaccharide saponins (91-93) and (94-96) in methanol with 1 N aqueous sodium hydroxide generated compounds (76-78). Similarly, the acetyl protecting groups of trisaccharide saponins (97-99) were removed by a solution of NaOH 1 N in methanol, giving the α- isomer products (76a-78a), (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12: Reagents and conditions (yields): (a) TMSOTf, CH2Cl2 , 0ºC (37% for 91, 35% for 92, 39% for 93, 34% for 94, 35% for 95, 36% for 96, 15% for 97, 13% for 98, 14% for 99); (b) 1N NaOH, MeOH, rt (89% for 76, 93% for 77, 90% for 78, 92% for 76a, 90% for 77a, 94% for 78a).

The anti-proliferative activity was evaluated for trisaccharide saponins (76-78) and (76a-78a) against MKN-45 and HeLa, two human tumor cell lines. Results showed that all the synthetic trisaccharide saponins exhibited moderate anti-proliferative activities (IC50:11 lM) against MKN-45 and HeLa tumor cells. The structurally derived saponins 76 and 77 and their α-isomer saponins (76a-78a), revealed similar IC50 values against both tumor cell lines as well as the natural saponin (76), which indicated that modification of sugar unit and conversion of glycosyl bond between the sugar chain and steroidal aglycon did not have any influence on the bioactivities displayed by these compounds. The results were compared with adriamycin, as a strong positive control [121-123].

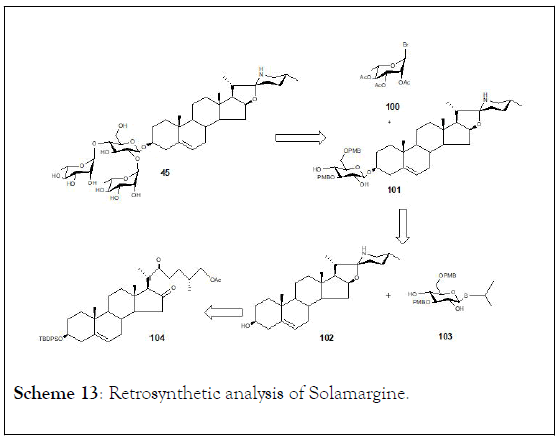

It synthesized solamargine (45), (25R)-3β-{O-Lrhamnopyranosyl-( 1→2)-[O-〈-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)]-β-Dglucopyranosyloxy}- 22-〈-N-spirosol-5-ene following a 13 steps synthetic pathway starting from the secondary metabolite diosgenin with a 10.5% yield (Scheme 13). The cytotoxic activity of synthetic solamargine (45) on HeLa, A549, MCF-7, K562, HCT116, U87, and HepG2 tumour cell lines, as well as two normal cell lines (HL7702 and H9C2), was assessed following the standard MTT assay [124]. Results showed that synthetic solamargine 45 exhibit cytotoxic activity with IC50 values ranging from 2.1 to 8.0 μM in all cell lines evaluated, but showed low cytotoxicity to the normal hepatocyte cell HL7702.

Scheme 13: Retrosynthetic analysis of Solamargine.

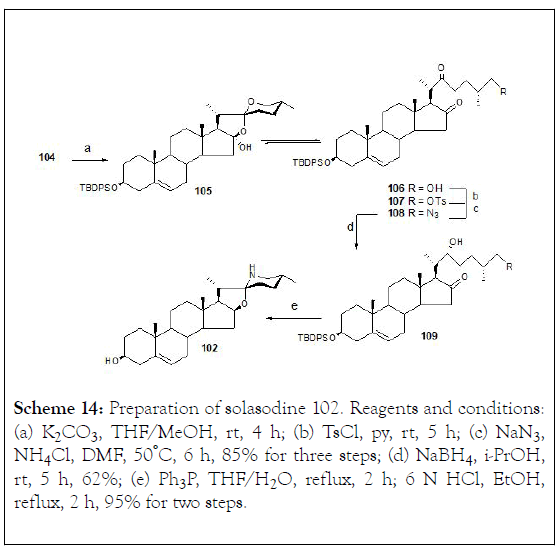

Treatment of (104) with K2CO3 in MeOH generated spiroketal (105) and its counterpart dione (106). These two compounds were found to be interconvertible in organic solution and consequently, the mixture of (105-106) was treated directly with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride/pyridine (→107), followed by azidosubstitution with NaN3 , to give (108). It has been well documented that selective reduction of the 16-ketone of the cholestan-16,22-dione with NaBH4 in i-PrOH provided the corresponding furostan through a concurrent intramolecular hemiketal formation. Applying the same idea, dione (108) was successfully converted into the hemiketal (109). The reductivecyclization of compound (109) was carried out in the presence of Ph3P under refluxing conditions, and followed by desilylation with 6N HCl to produce solasodine (102) (Scheme 14).

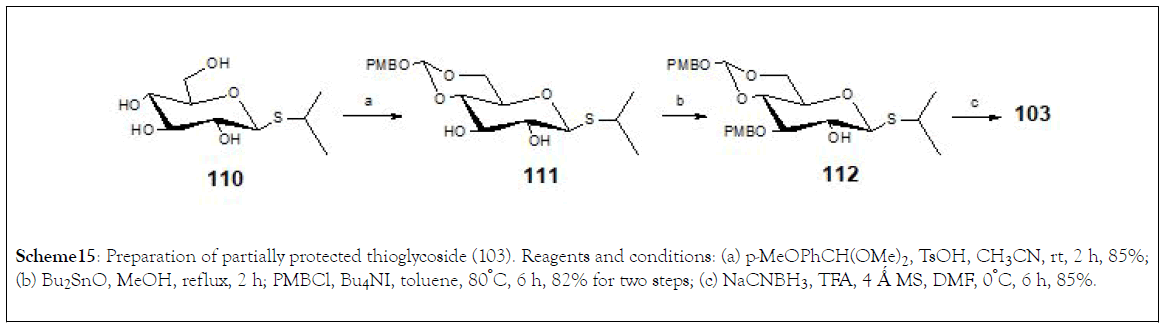

The partially protected thioglycoside donor (103) was prepared from compound (110) and p-methoxybenzylidenation of (110) with anisaldehyde dimethyl acetal ( → 111), followed by tinassisted regioselective p-methoxybenzylation, provided (112) from (110). Selective ring opening of (112) with sodium cyanoborohydride and trifluoroacetic acid afforded (103) (Scheme 15).

Scheme 14: Preparation of solasodine 102. Reagents and conditions: (a) K2CO3, THF/MeOH, rt, 4 h; (b) TsCl, py, rt, 5 h; (c) NaN3 , NH4Cl, DMF, 50°C, 6 h, 85% for three steps; (d) NaBH4, i-PrOH, rt, 5 h, 62%; (e) Ph3P, THF/H2O, reflux, 2 h; 6 N HCl, EtOH, reflux, 2 h, 95% for two steps.

Scheme 15: Preparation of partially protected thioglycoside (103). Reagents and conditions: (a) p-MeOPhCH(OMe)2, TsOH, CH3CN, rt, 2 h, 85%; (b) Bu2SnO, MeOH, reflux, 2 h; PMBCl, Bu4NI, toluene, 80°C, 6 h, 82% for two steps; (c) NaCNBH3, TFA, 4 Ǻ MS, DMF, 0°C, 6 h, 85%.

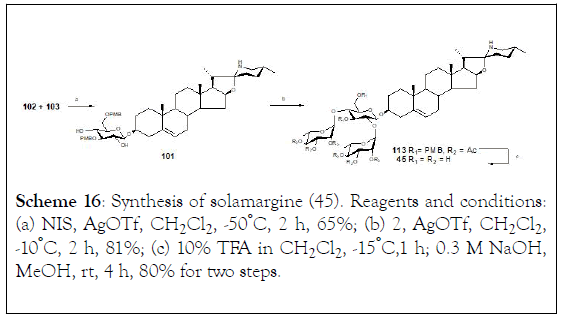

Coupling of solasodine (102) and a partially protected glycosyl donor (103) was carried out in dry methylene dichloride in the presence of AgOTf and N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) at -50°C generating the saponin (101). Moreover, condensation of (101) with (100) generated saponin (113). Finally, removal of the PMB groups from compound (113) by using 10% TFA in CH2Cl2 at -15°C, followed by deacylation with 0.3 M NaOH in MeOH afforded compound (45) (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16: Synthesis of solamargine (45). Reagents and conditions: (a) NIS, AgOTf, CH2Cl2 , -50°C, 2 h, 65%; (b) 2, AgOTf, CH2Cl2 , -10°C, 2 h, 81%; (c) 10% TFA in CH2Cl2 , -15°C,1 h; 0.3 M NaOH, MeOH, rt, 4 h, 80% for two steps.

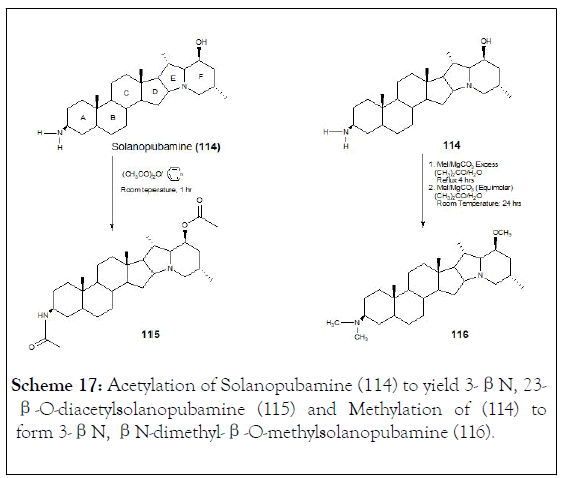

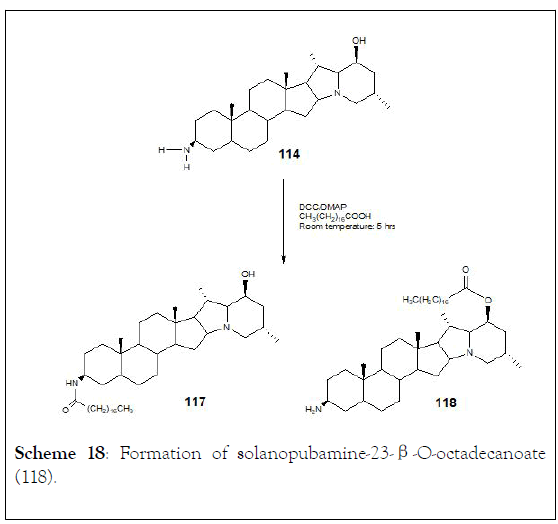

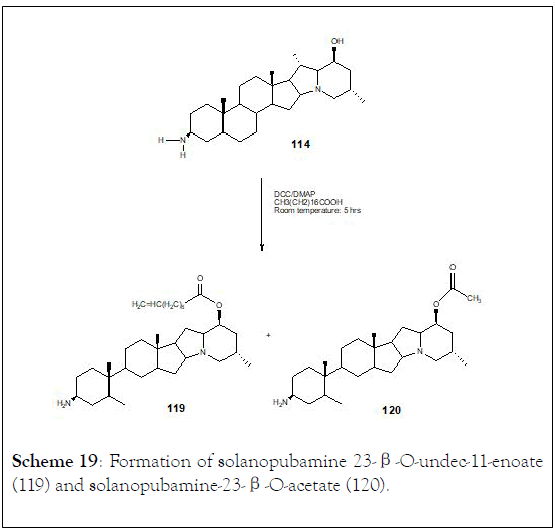

They were studied Solanopubamine (114) (3β-amino-5〈, 22- 〈H, 25β-H-solanidan-23β-ol) a steroidal alkaloid isolated from Solanum schimperianum. IR, positive ESI-MS, 1D and 2D NMR techniques, established the structure. The presence of 3β-NH2 and 23β-OH groups was achieved through methylation, acetylation or coupling with octadecanoic and undec-11-enoic acids to achieve six derivatives (115-120). Synthetic transformation of 3β-C-NH2 and 23β-COH of solanopubamine (114) was carried out in order to provide new semi-natural compounds, such as (116, 117, 118, 119 and 120), (Schemes 17-19) [125].

Scheme 17: Acetylation of Solanopubamine (114) to yield 3-βN, 23-β-O-diacetylsolanopubamine (115) and Methylation of (114) to form 3-βN, βN-dimethyl-β-O-methylsolanopubamine (116).

Scheme 18: Formation of solanopubamine-23-β-O-octadecanoate (118).

Scheme 19: Formation of solanopubamine 23-β-O-undec-11-enoate (119) and solanopubamine-23-β-O-acetate (120).

Solanopubamine and semi-synthetic analogs were investigated for their in vitro cytotoxicity against several human cancer cell lines (SK-MEL, human malignant melanoma; KB human epidermal carcinoma; BT-549, human ductal carcinoma; SKOV- 3, human ovary carcinoma; HL-60, human leukemia; VERO, monkey kidney fibroblast) and also to evaluate antimicrobial activity. Solanopubamine showed antifungal activity only against Candida albicans and Candia tenuis with MIC value of 12.5 g/mL. Semi-synthetic compounds (114-120) did not show neither anti-tumor nor anti-microbial activity.

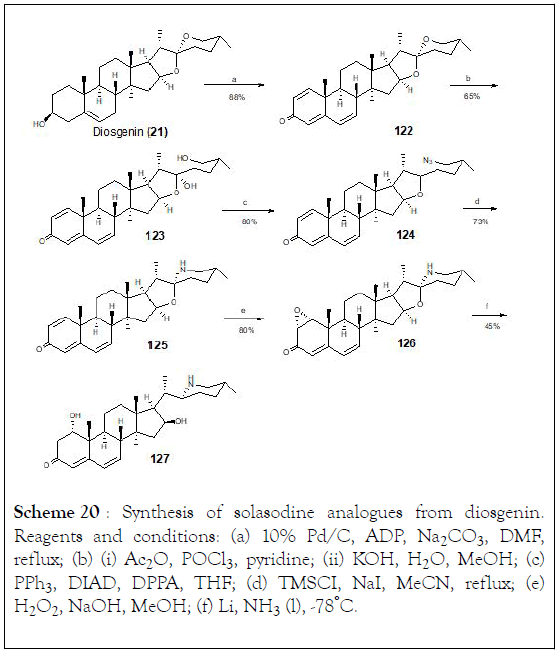

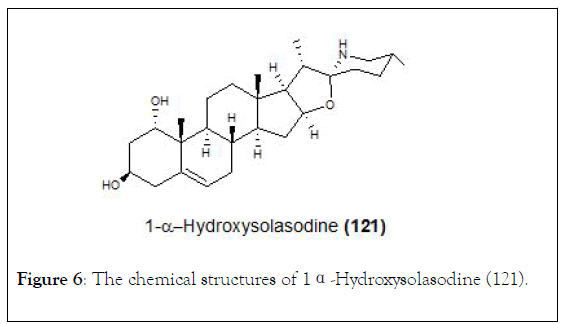

The search for new vitamin D analogues with a rigid side chain as a promising precursor containing a conformationally constrained spiro ring at the side chain is another topic of interest for researchers [126]. Thus, the synthesis of 1 〈- hydroxysolasodine (121, Figure 6) from diosgenin. In this investigation, all synthetic compounds as well as solasodine were evaluated for their cell growth inhibitory activity against human prostate cancer (PC3), human cervical carcinoma (Hela), and human hepatoma (HepG2) cell lines. During the process of synthesis, a Birch reduction of 1〈, 2〈-epoxy-4,6-dien-3-one analogue (126) led to an unexpected tetrahydrofuran ring opening product (127). The piperidine E-ring seems to have great impact on the chemical reactivity of solasodine. Regarding the cytotoxic activity only epoxide 126 displayed moderate inhibitory rates towards these cells (40%-54%) at the concentration of 10 M (Scheme 20).

Scheme 20: Synthesis of solasodine analogues from diosgenin. Reagents and conditions: (a) 10% Pd/C, ADP, Na2CO3, DMF, reflux; (b) (i) Ac2O, POCl3, pyridine; (ii) KOH, H2O, MeOH; (c) PPh3, DIAD, DPPA, THF; (d) TMSCI, NaI, MeCN, reflux; (e) H2O2, NaOH, MeOH; (f) Li, NH2 (l), -78°C.

Figure 6: The chemical structures of 1α-Hydroxysolasodine (121).

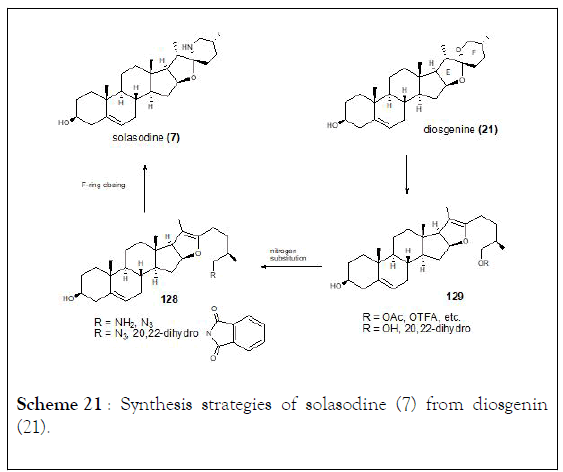

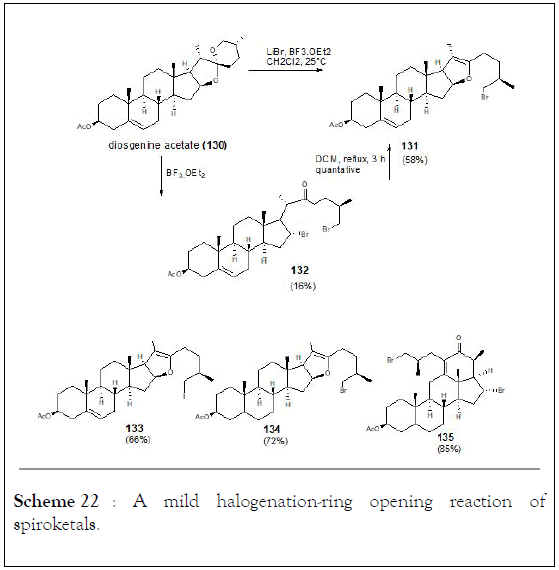

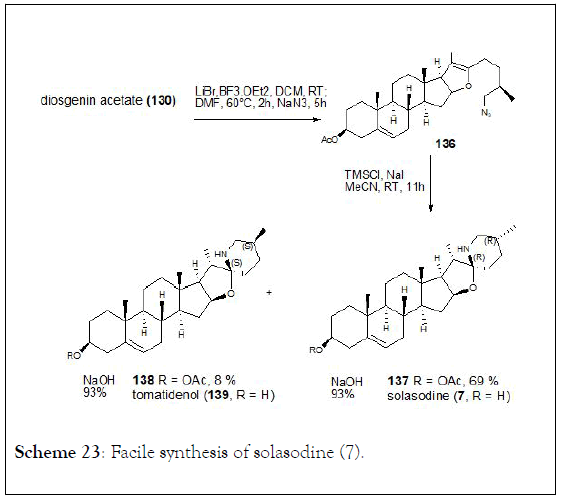

The halogenation-ring opening reaction of spiroketals in steroidal sapogenins at room temperature which provides x-halo enol ethers in high yields. Boosted by this method, solasodine known as an antitumor steroidal alkaloid was obtained from diosgenin acetate through three steps synthesis with an overall yield of 50%. In addition, the isomerization of C25 in steroidal alkaloids was observed and tomatidenol (139) was also prepared as side product. Authors were able to determine that configuration at C22 and C25 always appear in pairs (R,R or S,S) which might help to develop a stereoselective synthesis of tomatidenol (139), (Schemes 21-23) [127-130].

Scheme 21: Synthesis strategies of solasodine (7) from diosgenin (21).

Scheme 22: A mild halogenation-ring opening reaction of spiroketals.

Scheme 23: Facile synthesis of solasodine (7).

A number of investigations carried out with steroidal glycoalkaloids isolated from different Solanum species have demonstrated that these type of secondary metabolites have antifungal, trypanolytic, trypanocidal, larvicidal, molluscicide, acaricidal hepatoprotective, anti-ulcerogenic, anti-seizure, cytoprotective, neuro-pharmacological, antioxidative, antimicrobial and embryotoxic activities, as well as exhibit significant anticancer effect. In addition, studies have evidenced that steroidal glycoalkaloids, in particular, aglycones solanidine and solasodine have antitumor activity against many tumor cell lines. Thus, the increased interest of researchers to obtained these metabolites by synthetic pathway.

In this regard, eight solasodine derivatives have been obtained by synthesis revealing high antiproliferative activity. The possible effects of the sugar moiety present in glycoalkaloids have also been studied against cancer cells achieving promising results. Furthermore, solanopubamine and semi-synthetic analogs were investigated for their in vitro cytotoxicity against several human cancer cell lines exhibiting excellent cytotoxic activity. Due to the importance of these metabolites and their synthetic derivatives, research on this field should continue in order to obtain new compounds that might show a wide range of biological and pharmacological activities.

Citation: Morillo M, Rojas J, Lequart V, Lamarti A, Martin P (2020) Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity. Nat Prod Chem Res. 8:371. DOI: 10.35248/2329-6836.20.8.371

Received: 22-Jan-2020 Published: 12-Feb-2020, DOI: 10.35248/2329-6836.20.8.371

Copyright: © 2020 Morillo M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.