PMC/PubMed Indexed Articles

Indexed In

- Open J Gate

- Genamics JournalSeek

- JournalTOCs

- RefSeek

- Hamdard University

- EBSCO A-Z

- OCLC- WorldCat

- Publons

- Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research

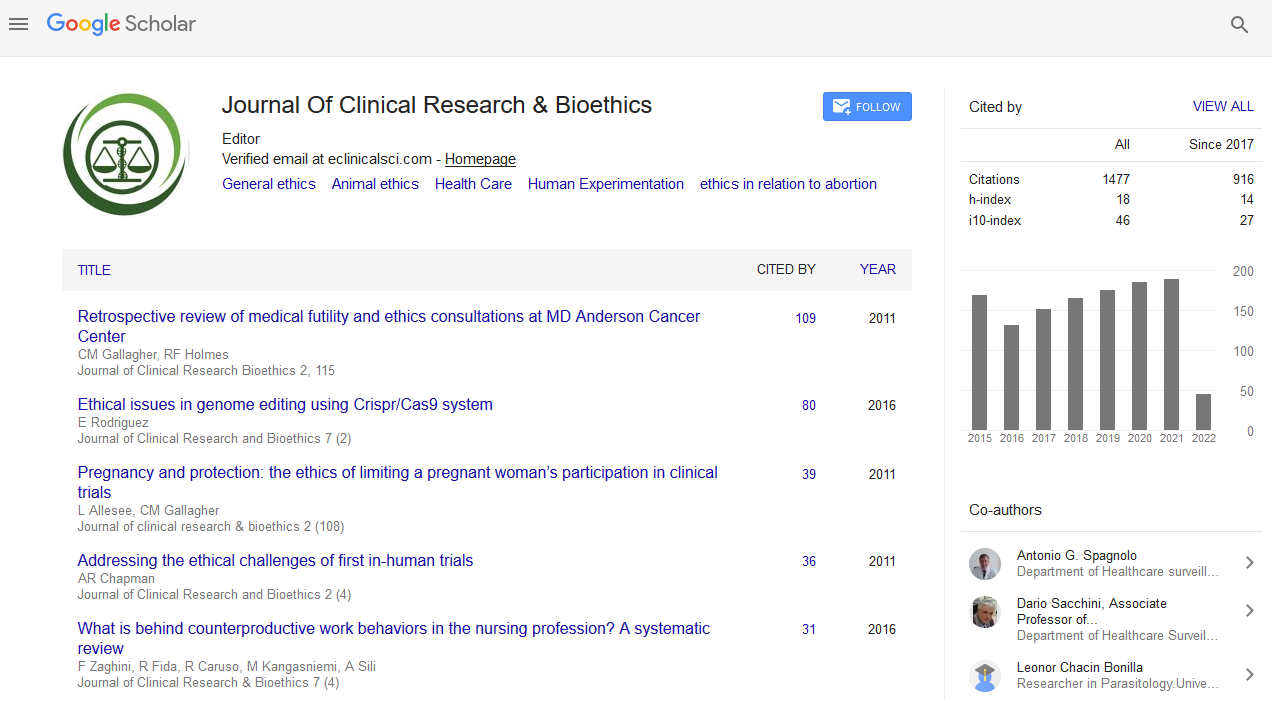

- Google Scholar

Useful Links

Share This Page

Journal Flyer

Open Access Journals

- Agri and Aquaculture

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics & Systems Biology

- Business & Management

- Chemistry

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- Food & Nutrition

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Medical Sciences

- Neuroscience & Psychology

- Nursing & Health Care

- Pharmaceutical Sciences

Research Paper - (2019) Volume 10, Issue 1

Healthcare Professionalsâ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care According to Autonomy of Practical Reason

Maia Goncalves A1,2*, Vieira A3, Vilaça A4, Maia Goncalves M5,6 and Meneses R52Instituto de Bioética, Universidade Católica Portuguesa 4169-005 Porto, Portugal

3Serviço de Pneumologia, Hospital de Braga, 4710-243 Braga, Portugal

4Serviço de Medicina Interna, Hospital de Braga, 4710-243 Braga, Portugal

5Instituto Universitário de Ciências da Saúde, 4585-116 Gandra, Porto, Portugal

6School of Literature and Languages, University of Surrey, Guildford GU2 7XH, UK

Received: 30-Mar-2019 Published: 22-Apr-2019

Abstract

Nowadays, innovative medical technologies almost mask death, although they are not free of ethical concerns. Regarding end-of-life decisions, publications demonstrate that doctors don’t intend for themselves what they practice with patients.

We aimed to assess health professionals’ perspectives about their own end-of-life decisions, asking them “In case of advanced oncological disease, would you prefer rescue or comfort therapy?” and “In case of advanced chronic disease, would you prefer admission in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or palliative care?”.

The sample included 57% doctors. 80% of all participants chose comfort therapy and 84% chose palliative care. Nurses chose comfort therapy and palliative care more frequently than doctors (p<0.05); both doctors and nurses from surgical areas preferred rescue therapy and ICU admission (p<0.05); more than half of pediatricians answered rescue therapy and ICU admission, this trend was also observed in oncologist/palliative care doctors and surgeons, with a statistical difference (p<0.05) compared to other doctors; on the opposite, 90% from Emergency and Intensive Medicine doctors answered comfort therapy and palliative care (p<0.05).

Communication with patients and families must be more effective, making them understand that the appropriate clinical decision is the most ethically correct. Death is not something to be avoided at all costs, but rather a moment on life cycle. These issues should be discussed in advance, anticipating the possible need for admission to ICU, rescue therapy or setting limits and gently stops.

Keywords

End-of-life Care; Autonomy; Ethics; Communication; Doctor-patient relationshipIntroduction

The respect for the Autonomy principle in the doctor-patient relationship makes it clear that doctors, who are in possession of scientific knowledge, know how to and should inform patients about the different possible responses for the patient’s clinical situation. However, the patients are probably the ones in the best position to decide what is in their best interest and thus to decide which treatments they are willing to be subjected to [1].

In this sense, autonomy as described by Kant [2] is opposed not only to the heteronomy of the selfish nature of the sensible inclinations but equally to the heteronomy of the moral and religious dogmatism. The author of the “Kritik der pratischen Vernunft” (Critique of Practical Reason) claimed that the true essence of the moral act does not reside in the belief of another world beyond telluric life but rather in the obedience to the “ummittilbare sittliche Vorschriften” (indeterminate moral determinations) that a man finds at heart. Indeed, the autonomy implies the refusal of theonomy, making it a commandment of “Vernunft” (reason), because a man must obey to the “moral law” (moralisches Gesetz) which is expressed with immediacy in his will.

This is the moral faith which depends on the “gutter Wille” (good will). The autonomy that is proposed to us by Kant is to be practiced by each individual as a person, meaning as a member of a humanitas, composed per se in a “kingdom of ends”, imposing itself upon the conscience of each person and demanding that one should not decide against it.

The Grundlagen of Kant define a freedom which is transcendental (intelligible and that conditions a priori the possibility of concrete acts in the sensible world) and practical in the sense of the moral autonomy of the will (Wille). The transcendental freedom moves to the background plane whilst the “practical freedom” as a form of autonomy, rises to the front plane. The autonomy preserves the definition of the transcendental freedom as causality which is spontaneous, intelligible, unconditional and independent from natural causality. Naturally, the autonomy is not only the supreme principal of morality but also the “key-concept” which ensures the passage from the analytic method to the synthetic method, meaning the The Metaphysics of Morals to Critique of Practical Reason.

In terminal situations, for example in the case of refractory oncological illness or an advanced phase of an exacerbated chronic disease, there is often the necessity to consider the transition from curative to comfort therapy [3].

The necessity to make this transition is not always clear, the main barriers being: the situations might not be clinically obvious; the doctor may be unable to realize that a given treatment is too aggressive and possibly a futile therapy; the patient and their family often have difficulty in accepting the interruption of chemotherapy; sometimes doctors are reluctant to communicate or have deficient communication; the existence of differences at a cultural, linguistic or religious level; and lastly, the physical or/and pharmacological unavailability to engage in comfort therapy [4,5].

End-of-life care must always respect the will of the patient. The doctor must be the faithful carrier of the last wishes expressed by the patient regarding the treatments that the latter is willing to be subjected to. Therefore, there must be an anticipatory discussion of the potential outcomes, a personalized and multidisciplinary following of the patient’s condition, knowledge of the aspirations of the patient and their family and the establishment of a treatment plan [6].

However, the culture of avoiding death in hospitals for acute patients continues to be a considerable obstacle for end-of-life care, even when the adequate resources to are available [7]. The question that should be asked is if the healthcare professionals respect the patient’s right to autonomy in its full integrity, particularly when there are no more clinical solutions from a curative perspective. If the communication in the doctor-patient relationship is efficient, probably the patient’s choices are like those that the doctor would make for himself if he was in the patient’s position. It was in this line of reasoning that a questionnaire was distributed among healthcare professionals, concerning what treatments they would choose for themselves if they suffered from refractory oncological illness and if in the context of an advanced chronic disease they would rather be admitted for intensive care or palliative care.

Methods

The purpose of our study was to assess health professionals’ perspectives about personal end-of-life decisions.We conducted a survey directed to doctors and nurses working in Hospital de Braga (Braga, Portugal) with demographic data and 2 questions, to be answered Yes or No: “In case of advanced oncological disease, would you prefer rescue or comfort therapy?” and “In case of advanced chronic disease, would you prefer admission in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or in a Palliative Care Unit?”.

Our main objectives were to describe participants’ opinion about personal end-of-life decisions and to find any statistical differences between groups, namely type of health professional, main professional area, age and sex. Our working hypothesis was the following: H1) medical doctors’ answers are different than nurses’ answers; H2) the answers are different according to the professional area in the hospital; H3) older professionals’ answers are different than younger professionals’ answers; H4) male’s answers are different than female’s answers.

Results

The sample included 500 participants, mostly male (n=302, 60.4%) with a mean age of 36 ± 9 years-old, 42% (n=209) between 30 and 39 years-old, as detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

| Variables | Age intervals | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 36 | 20-29 | 137 (27.4) |

| Standard-deviation | 9 | 30-39 | 209 (41.8) |

| Mode | 29 | 40-49 | 103 (20.6) |

| Median | 33 | 50-59 | 45 (9) |

| Min/Max | 22/75 | ≥60 | 6 (1.2) |

Table 1: Sample characterization by age.

| Gender | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 302 (60.4) |

| Female | 198 (39.6) |

Table 2: Sample characterization by gender.

The sample was composed of 294 (56.8%) medical doctors and 216 (43.2%) nurses (Table 3).

| Job | Frequency (%) | Professional area | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical doctor | 294 (56.8) | Medical | 173 (34.6) |

| Nurse | 216 (43.2) | Surgical | 155 (30.9) |

| - | - | Oncology/Palliative Care | 32 (6.4) |

| - | - | Pediatrics | 21 (4.2) |

| - | - | Emergency Department | 66 (13.2) |

| - | - | Intensive Care | 31 (6.2) |

| - | - | General Practice | 22 (4.4) |

Table 3: Sample characterization regarding job and professional area.

Question 1: “In case of advanced oncological disease, would you prefer rescue or comfort therapy?”

In respect to the first question, 80% of all participants chose comfort therapy.

Comparing medical doctors’ and nurses’ answers (H1), the majority chose comfort therapy (Table 4); by the use of a Chisquare test (Chi-square-test χ2(1,n=500)=22.9, p<0.001; Phi=0.214), we found a significant trend for medical doctors (28%) to choose rescue therapy more than nurses (10%).

| Variable | Question 1 | χ2Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rescue therapy | Comfort therapy | |||

| Job | Medical doctor | 78 (28%) | 206 (73%) | χ2=22.9 |

| Nurse | 22 (10%) | 194 (90%) | p<0.001; Phi=0.214 | |

Table 4: Answers to Question 1 by job (Frequency table and significance test).

Interestingly, the answer was also different according to the professional area (H2): There was a significant trend for surgical and pediatric professionals to choose rescue therapy and for emergency department’s professionals to choose comfort therapy (Chi-square-test (χ2(6,n=500)=44.0, p<0.001; Phi=0.297).

Regarding age (H3), we found no statistical difference between younger and older participants (t-student test for independent samples (t(498)=-0.610, p=0.542).

Concerning gender (H4), men’s answer was different from women’s answer (Chi-square-test (χ2(1,n=500)=6.79, p=0.009; Phi=0.117): Although the majority chose comfort therapy, there was a significant trend for men (26%) to choose rescue therapy more than women (16%).

In search for a predictive model and trying to analyze data with a holistic view, we performed a binary logistic regression model with the variables type of health professional, professional area, age and sex and we found a significant trend for doctors to choose rescue therapy and for surgical specialties to choose rescue therapy (Table 5).

| Variables | B | S.E. | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender | 0.309 | 0.249 | 1.362 | 0.836 | 2.219 |

| Age | -0.01 | 0.013 | 0.99 | 0.966 | 1.015 |

| Health professional | 1.165 | 0.274 | 3.205*** | 1.874 | 5.48 |

| Medical specialty | -0.118 | 0.327 | 0.889 | 0.468 | 1.686 |

| Surgical specialty | 0.816 | 0.29 | 2.262** | 1.281 | 3.994 |

Table 5: Binary logistic regression model-Question 1. * p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Question 2: “In case of advanced chronic disease, would you prefer admission in an ICU or in a Palliative Care Unit?”

In respect to the second question: 84% of all participants chose palliative care.

Comparing medical doctors’ and nurses’ answers (H1), the majority chose admission in a Palliative Care Unit; we also found (Chi-square-test (χ2(1,n=500)=19.4, p<0.001; Phi=0.197) a significant trend for medical doctors (23%) to choose admission in an ICU more than nurses (8%). Once again, the answer was different according to the professional area (H2): There was a significant trend for surgical and pediatric professionals to choose admission in ICU and for medical departments’ professionals to choose admission in a Palliative Care Unit (Chisquare- test (χ2(6, n=500)=48.5, p<0.001; Phi=0.311).

Regarding age (H3), we also found no statistical difference between younger and older participants (t-student test for independent samples (t(498)=-1.766, p=0.078).

Concerning gender (H4), there were different answers too (Chisquare- test (χ2(1,n=500)=24.5, p<0.001; Phi=.221): Although the majority chose palliative care, there was a significant trend for men (26%) to choose admission in an ICU more than women (10%).

We used the same binary logistic regression model and we found a significant trend for men and doctors to choose admission in ICU and for medical areas to choose the other option (Table 6).

| Variables | B | S.E. | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender | 0.891 | 0.273 | 2.438** | 1.427 | 4.164 |

| Age | -0.003 | 0.014 | 0.997 | 0.971 | 1.024 |

| Health professional | 1.225 | 0.307 | 3.402*** | 1.865 | 6.207 |

| Medical specialty | -0.789 | 0.369 | 0.454* | 0.22 | 0.937 |

| Surgical specialty | 0.263 | 0.298 | 1.301 | 0.726 | 2.33 |

Table 6: Binary logistic regression model-Question 2.*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Discussion

In response to the first question: “In case of advanced refractory oncological disease, would you choose rescue therapy or comfort therapy?” 80% of all participants said they would choose comfort therapy.

Regarding the second question: “In case of exacerbation of advanced chronic disease, would you rather be admitted in an ICU or in a palliative care unit?” 84% of all participants chose palliative care. The statistical analysis, which included binary logistic regression, made it possible to identify a smaller tendency of surgical doctors and pediatricians to choose comfort therapy. It also identified greater unanimity of nurses and other medical specialties in choosing comfort therapy.

The answers to both questions show that the majority of healthcare professionals would prefer comfort therapy. However, in clinical practice it is seldom clear when is the best moment to propose to the patient a transition to comfort therapy. For example: There is a patient who is over 80 years old and suffers from cardiac and chronic respiratory failures, who has had several respiratory infections over the past few years which led to hospitalization due to unbalance of these chronic conditions. When is the right moment to propose to this patient the transition to comfort therapy? To take this decision only when the patient is physically drained to a significant extent resulting in considerable limitations in the performance of his daily activities is not the most adequate clinical decision. A timelier decision would serve palliative care better, ensuring greater comfort and improving life quality. It should be noted that there have been several instances in which after treatment during hospitalization, it was possible to cure the infection and optimize the cardio-respiratory failure, enabling the patient to go home. However, after each hospitalization the patient returned home with increased debility, increased functional limitation and increased dependency. There is a time within the context of functional limitation, symptom relief (particularly shortage of breath and asthenia) and pain complaints, where a support characterized by an adequate nutrition, regularized sleep patterns and some psychological support would prove more beneficial for the patient rather than waiting for new infection and hospitalization. Maybe in the future we should consider overlapping curative and palliative care. And we should do it earlier in the progression of chronic diseases. Despite this, in clinical practice, intensivists are confronted with solicitations for admissions in the ICU in cases where palliative care would be more suitable [8,9].

Those solicitations often occur in situations of clinical urgency or emergency in which the decision to implement advanced life support measures results from therapeutic fixation [10].

Regardless of all the optimization methodologies of the admission in ICU decision process, in clinical practice this is always a complex decision because the refusal of admission may objectively result in the death of the patient [11].

In oncological disease, it’s clear that the patients often benefit from the intensive care support, namely after surgery, in the treatment of infectious complications and of iatrogenic consequences of chemotherapy and radiotherapy [12]. When the oncological disease develops despite the implemented therapeutic measures and the patient shows a simultaneous cachexia aggravation, admission of such a patient in the ICU would be therapeutic fixation [13]

The transition from a curative care to comfort care is a clinical decision that should be discussed in anticipation with the patient and their family.

A good doctor-patient communication is probably the central tool in the framing of an efficient and therapeutic doctor-patient relationship, crucial for providing quality healthcare. A significant amount of patient unsatisfaction and complaints derived from a deficient doctor-patient relationship [14].

Many doctors tend to over-estimate their communication skills [15,16].

Over the years, much has been published about communication in the doctor-patient relationship. The implementing of a patient-centred medicine is the opportunity for a considerable improvement of this communication [17].

Regardless of all the communication optimization strategies, one of the most common flaws according to the authors is the failure to timely discuss prognostics and therapeutic options that will exist in advanced and/or refractory phases of the disease. In a patient with cardiac failure, a chronic respiratory failure or a renal failure, in the early stages of the disease, the patient’s future wishes are rarely discussed [18].

In very advanced stages of the disease, when the patient is debilitated, the time frame which would allow for the respect of the patient’s autonomy has already been lost.

We also must consider the entire process of the disease, particularly in life-threatening diseases, because it is a process which is painful both physically and emotionally and that is often very long. It may lead to exhaustion, depression and innumerable doubts in the patient’s mind regarding the real worth of the treatment [19]. The disease becomes a burden that extends to the patient’s family and friends and it is common for the patient to worry about becoming a burden to the family [20]. The rudimentary level of knowledge in terms of health science on behalf of most patients, allied to the reading of non-reliable online resources, may be detrimental for the communication in the doctor-patient relationship. The patient and their family often have their own convictions inspired by these non-reliable sources which sometimes become an obstacle for the building of trust towards the doctor [21].

The communication in the doctor-patient relationship has many obstacles which have the potential to undermine its efficiency and therapeutic nature. There should be an empathy based on communication and an efficient exchange of information, ensuring the respect of the patient’s autonomy but fuelled by compassion. “The patient will never care how much you know, until they know how much you care” [22]. In a simplified way, compassion on behalf of the doctor implies sensitivity towards the suffering of others and taking the compromise to avoid it and prevent it.

Those who have the experience to apply the principle of respect for autonomy, namely to reach a decision of consent or refusal for an act of medical intervention, are well aware of how hard the application of this principle is and also of how we ultimately attribute arbitrary values to the item “good understanding” and to the item “absence of influences” to obtain a result about the autonomy, as a means to ease our own ethical consciousness. If in daily life absolutely autonomous decisions are a rare exception, we may ask ourselves as do the pragmatics: why be so demanding in healthcare decisions? In practical terms, many doctors accept the minimalist position in the evaluation of autonomy and take refuge in common sense and in good practice and customs, as stated by Daniel Serrão [23]. For rescue therapies and/or comfort therapies to be applied, according to Bioethics, we need to experience not only the principle of respect for autonomy but also the principles of Justice and of Beneficence and of Non-Maleficence.

All the principles of Beauchamp and Childress are at stake in order to, in the just and adequate form, imply the risks and benefits associated to the therapies of rescue and comfort being addressed [24].

Conclusion

This study shows that if in a terminal situation the healthcare professionals tend to prefer comfort therapy for themselves. However, in clinical practice, the solicitations for admission in ICU of patients with advanced chronic illnesses and the implementing of rescue therapies in patients with refractory oncological diseases, is still very frequent. The results of this study suggest there is the necessity to better reflect on these decisions.

The authors suggest that emphasizing the communication between the doctor and the patient can lead to greater respect for the autonomy of the patient and consequently, to a better healthcare service.

A defensive medicine is detrimental for a more genuine relationship between doctor and patient, in which the information and communication must flow with the sole purpose of rightful respect for the autonomy of the patient without any preoccupation on behalf of the doctor at a legal and defensive level.

Lastly, the results of this study may also suggest that doctors still have inhibitions when it comes to addressing death with patients.

Respect for patient autonomy should be an opportunity to better care, can help avoiding medical futility, and will surely, improve communication and strengthen the doctor-patient relationship.

If autonomy is indispensable to ponder the possibility of a moral action, Kant does not state that it rules all our actions. The value of the categorical imperative does not reside in the moral actions where it is a criterion, but rather exists at the expense of other imperatives (hypothetical) which incline the desires of men and the respect for social traditions, as should be seen in the doctor-patient relationship.

The moral of autonomy does not lead to the excessive moralization of human life, in the sense that all human actions ought to be judged by this principle. Kant leaves out space for other maxims, such as those by “Pflicht”. However, the philosopher of Konigsberg admits that certain natural inclinations force the efficiency of moral maxims. Kant provided, with the autonomy, a new foundation to ethics and a new evaluation criterion (the categorical imperative), as well as a new formula that did not suppress other moral actions. Kant shows that the reality of morality is laid on a particular experience a priori as that of the moral law on us, an experience infinitely clearer than the entire sensible experience.

The pure fact of reason (autonomy) helps us understand the voice of the moral law and shows us the divine part of ourselves. Naturally, in end of life, the autonomy of the patient may be limited to the extent of the natural progression of the disease. The progression of the disease will condition the selfdetermination of the patient, who may need the support of family on the face of end of life clinical decisions.

Some clinical decisions, such as the informing of the patient about the progression of terminal illnesses, may not be judged by the autonomy principle regarding Kantian Deontology.

We can also say that comfort therapies imply declarative value and meaning, in order to relate to the principle of respect for autonomy with the principles of beneficence and of nonmaleficence.

According to Bioethics, it may be necessary, to ponder decisions regarding terminal patients, for doctors to follow other principles of the Beauchamp and Childress, such as beneficence and non-maleficence, whether regarding clinical information or therapies, establishing a new ethical pedagogy for a new moral conduct in end of life.

REFERENCES

- Benaroyo L. Can we accept medical progress without progress in ethics? J Int Bioethique. 2013;24(2-3):23-42.

- Kant I. Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten. In: Werke K, Band IV, Berlin, Walter de Gruyter & Co.,1968;pp. 446-456.

- Gott M, Ingleton C, Bennett MI, Gardiner C. Transitions to palliative care in acute hospitals in England: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1773.

- Oude Engberink A, Badin M, Serayet P, Pavageau S, Lucas F, Bourrel G. Patient-centeredness to anticipate and organize an end-of-life project for patients receiving at-home palliative care: A phenomenological study. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):27.

- Geiger K, Schneider N, Bleidorn J, Klindtworth K, Junger S, Muller-Mundt G, et al. Caring for frail older people in the last phase of life-The general practitioners' view. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:52.

- Sercu M, Renterghem VV, Pype P, Aelbrecht K, Derese A, Deveugele M. It is not the fading candle that one expects: General practitioners' perspectives on life-preserving versus "letting go" decision-making in end-of-life home care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):233-242.

- Reid C, Gibbins J, Bloor S, Burcombe M, Mc Coubrie R, Forbes K. Healthcare professionals' perspectives on delivering end-of-life care within acute hospital trusts: A qualitative study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(5):490-495.

- Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A. Palliative care in intensive care units: Why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18:106.

- Coelho CBT, Yankaskas JR. New concepts in palliative care in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter. Intensive. 2017;29:2.

- Montgomery H, Grocott M, Mythen M. Critical care at the end of life: Balancing technology with compassion and agreeing when to stop. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119(1):i85-i89.

- Roshdy A. Admission to the intensive care unit: The need to study complexity and solutions. Ann Intensive Care. 9:14.

- Koch A, Checkley W. Do hospitals need oncological critical care units? J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(3):E304.

- Pope MT. Legal duties of clinicians when terminally Ill patients with cancer or their surrogates insist on ‘Futile’ treatment. The ASCO Post. 2018.

- Minhas R. Does copying clinical or sharing correspondence to patients result in better care? Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(8):1390-1395.

- Osuna E, Perez Carrion A, Perez Carceles MD, Machado F. Perceptions of health professionals about the quality of communication and deliberation with the patient and its impact on the health decision making process. J Public Health Res. 2018;7(3):1445.

- Gallagher T, Levinson W. A prescription for protecting the doctor-patient relationship. Am J Manag Care. 10:61-68.

- Barry MJ, Edgman Levitan PA. Shared decision making-The pinnacle of patient-Centered Care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780-781.

- Sandman L, Munthe C. Shared decision making, paternalism and patient choice. Health Care Anal. 2010;18(1):60-84.

- Frenke M. Refusing treatment. Oncologist. 2013;18(5):634-636.

- Carlson RH. Understanding the emotions of patients who refuse treatment. Oncology Times. 2014(36):22:29.

- Paiva D, Silva S, Severo M, Moura Ferreira P, Lunet N, Azevedo A. Limited health literacy in portugal assessed with the newest vital sign. Acta Med Port. 2017;30(12):861-869.

- Canale T. Vice Presidential Lecture. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. 2000.

- Serrao D, Meneses R. Autonomia em Kant: Pela critica da critica cientifica, Revista de Filosofia. 2010;35:7-19.

- Borges Meneses RD: Principialismo e Pedagogia Ética. In: Eikasia. 2004:4-25.

Citation: Maia Goncalves A, Vieira A, Vilaça A, Maia Goncalves M, Meneses R (2019) Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on End-of-Life Care According to Autonomy of Practical Reason. J Clin Res Bioeth. 10:333.

Copyright: © 2019 Maia Goncalves A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.